In Ancient Egypt, the female pharaoh Hatshepsut chose to rule as a king, assuming traditional kingly regalia and adopting a fake beard and male clothing. Kabuki, the classical Japanese dance-drama, famously boasts all-male casts, but it in fact began as an all-female performance art, known as onna-kabuki—until women were banned from it in 1629 for being too erotic, and the all-male tradition took over. Many consider kabuki to be the first form of pop culture in Japan, something that chimes with the surge in mainstream popularity of drag in recent years, led by Rupaul’s Drag Race. Few know about Yeoseong Gukgeuk however, a genre of Korean theatre that features exclusively women actors that reached its peak of popularity in the 1950s and 1960s. Reinventing the traditional Korean theatre, they brought the process of gender-shifting to the limelight and subverted socially acceptable norms by blurring conventional gender binaries.

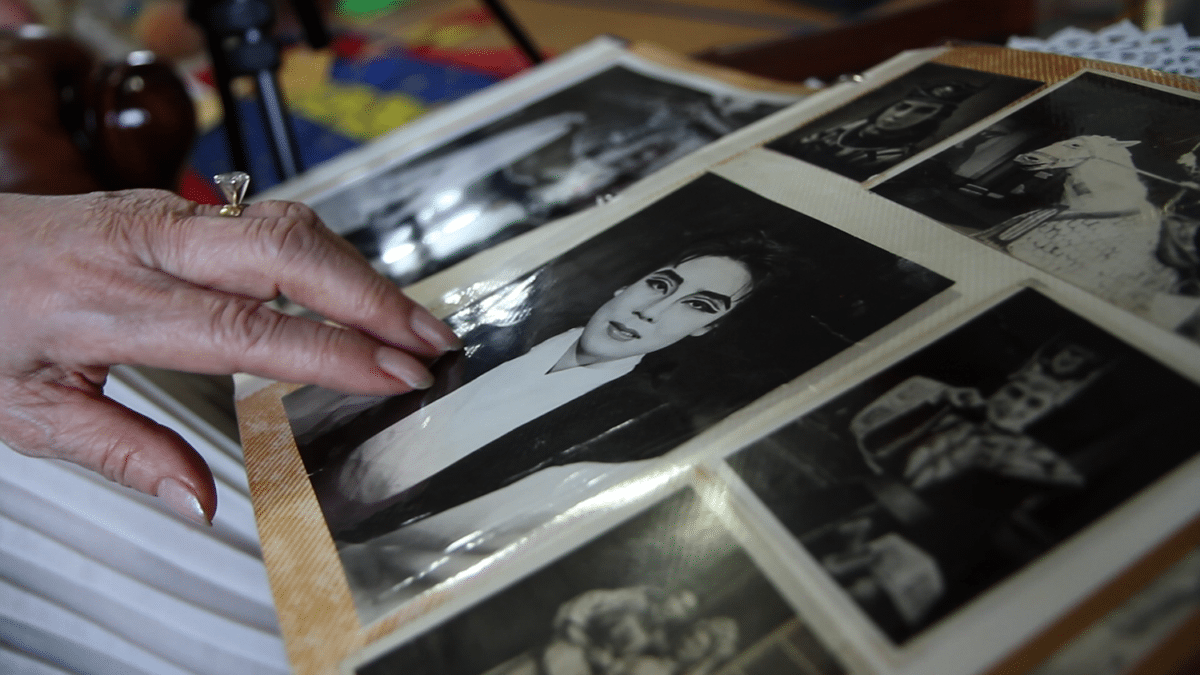

Since 2008, Siren Eun Young Jung has investigated the public and private lives of Yeoseong Gukgeuk performers who, after the genre fell out of favour, went on to live disparate lives. She works with archival materials through an intensive research process, conducted over the course of the last decade, to weave together queer desires and patterns of resistance, affective matters and subversive subjectivities, gender fluidity and the performance of difference. A member activist artist within the feminist and LGBT groups at Ewha Women’s University, which she attended during the 1990s, she later moved to the UK to study amidst the second-generation feminist art movement before returning to Seoul. She has just been announced as one of the artists selected to represent Korea at the 2019 Venice Biennale, where she will present a new iteration of the project.

How did you become interested in the vanished genre of all-female Korean opera performances?

In Japan they have a similar genre of all-female performance, called “Takarazuka”, and I was interested in it when I was young. It was only later I discovered that in Korea we have a very similar type of genre called “Yeoseong Gukgeuk”. From 2008, I started to deepen my knowledge of it by first collaborating with researchers who studied the broader culture of Korea in the 1950s, and this is how I got to know about Gukgeuk.

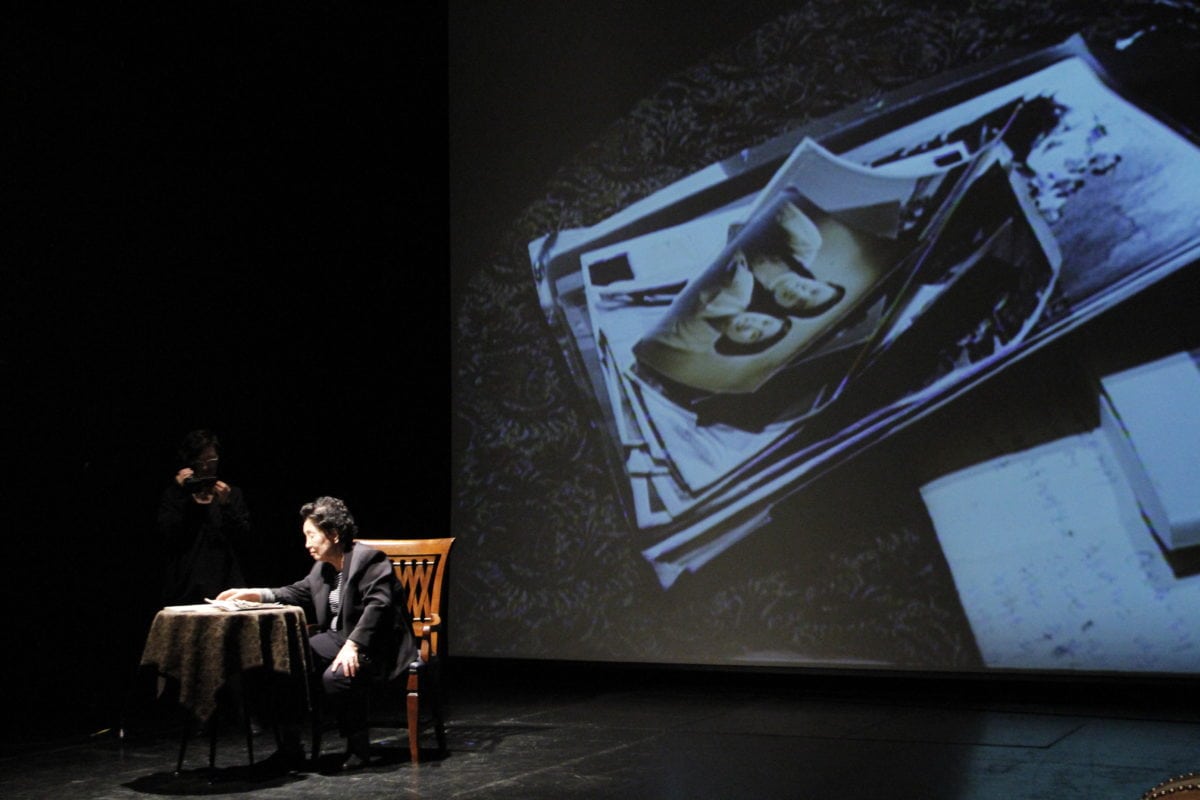

- Act Of Affect, 2013

Female Gukgeuk is almost in extinction as a form of theatre due to the military government of Park Chung-hee, who wanted to modernise Korea and make a strong nation back in the sixties and seventies. Under this slogan he created what he called “traditional” forms of culture. In the process he discarded the drama of female Gukgeuk, although it was very popular back in the day, just because it consists entirely of women. That is why it has been forgotten by many people. Against this historical background, I wanted to bring out the important aspect of resistance.

Fortunately there are still some living actresses, who played the male roles from both the first generation (1930s to 1960s) and second generation (from the 1960s onwards), that I was able to meet when I started my research. Most of all, I wanted to focus on issues around minority and tradition, modernity and sexual normativity, that these operas inevitably raise.

“I wanted to focus on issues around minority and tradition, modernity and sexual normativity, that these operas inevitably raise”

- (Off)Stage Masterclass, 2013

Androgyny, drag and LGBT rights are gaining greater visibility than ever in the art world of late, with major exhibitions such as David Wojnarowicz at the Whitney in New York and DRAG at the Hayward Gallery in London. How does it feel to see this new public interest in the topic in recent years?

This topic is one of my personal interests, and it has a relationship to my background and how I grew up and my links to the Korean feminist community, but it also has another meaning. It is a form of resilience or political language. The fact that this work is exhibited in a public institution like MMCA in Seoul, in the context of a very conservative society like Korea, is extremely meaningful to me while having a very political aspect to it too.

- Off Stage Lee So Ja, 2012

How big is the international Me Too movement in Korea, and what has been your experience of the ongoing conversation around it in recent months?

The Me Too movement is very strong here in Korea as well. It’s having a big response from the public. It means that there is light being shed once again on the feminist movement here. New discussions and perspectives on these topics are becoming required once again in our society. But nevertheless, despite the spread of the Me Too movement across the country, our society remains strongly very anti-feminist. The capacity of people in Korea to embrace such topics is very vulnerable, very weak. Even in the arts scene, it’s still very male-oriented. That’s why I think my work has a sense of crisis in that aspect, and I think that is why more have people looked at it and raised new questions within this topic of the historic all-female opera.

How do you approach working with both video and live performance to interpret and represent classical opera?

I regard myself primarily as a video artist, and so when I first met the female actresses who perform onstage and went into their communities I started by using video as my medium to document their lives. This was from 2008 to around 2012, but I later started to realise that there are meanings that cannot be collected through video alone. This is how I came to change my form a little bit. The people who I meet are mostly actresses who perform onstage, who feel most comfortable with the stage because that is where they spend the majority of their working life. This is why I asked them to go onstage, and why I began to convert my role from video to stage or performance director. Nevertheless, video is still extremely important to my work.

“The people who I meet feel most comfortable with the stage because that is where they spend the majority of their working life”

- Anomalous Fantasy (Korea Version), 2016

How has the shift to performance changed the work, particularly with the introduction of a live audience?

The meaning of my work itself does not change, but my attitude to my work changes and my perspective and how I perceive things changes when working with the medium of performance. As I used to work with video only, I would be alone in my small studio to spend a lot of time editing the video works. That is how I mostly spend my time as a video artist. Dealing with performances, I now have elements that I cannot control, like real-time mistakes and the emotions of the actresses, and the response of the audience. Of course, when I began to work with the unpredictable aspects of performance I was a quite nervous, However, I now view these elements that I cannot control as something that has the potential to make my work truly alive.

Korea Artist Prize 2018

At National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art Korea until 25 November

VISIT WEBSITE