Sofia Mitsola tries to paint the body “as it feels rather than as it looks”. Even in the early days of her practice, while receiving a classical art education in her home city of Thessaloniki, she was more interested in conjuring “emotional or erotic states” than rendering the world “as it is”. As such, the larger-than-life fantasy figures she’s become renowned for are drawn as much from the pages of Playboy as they are from Ancient Greek mythology.

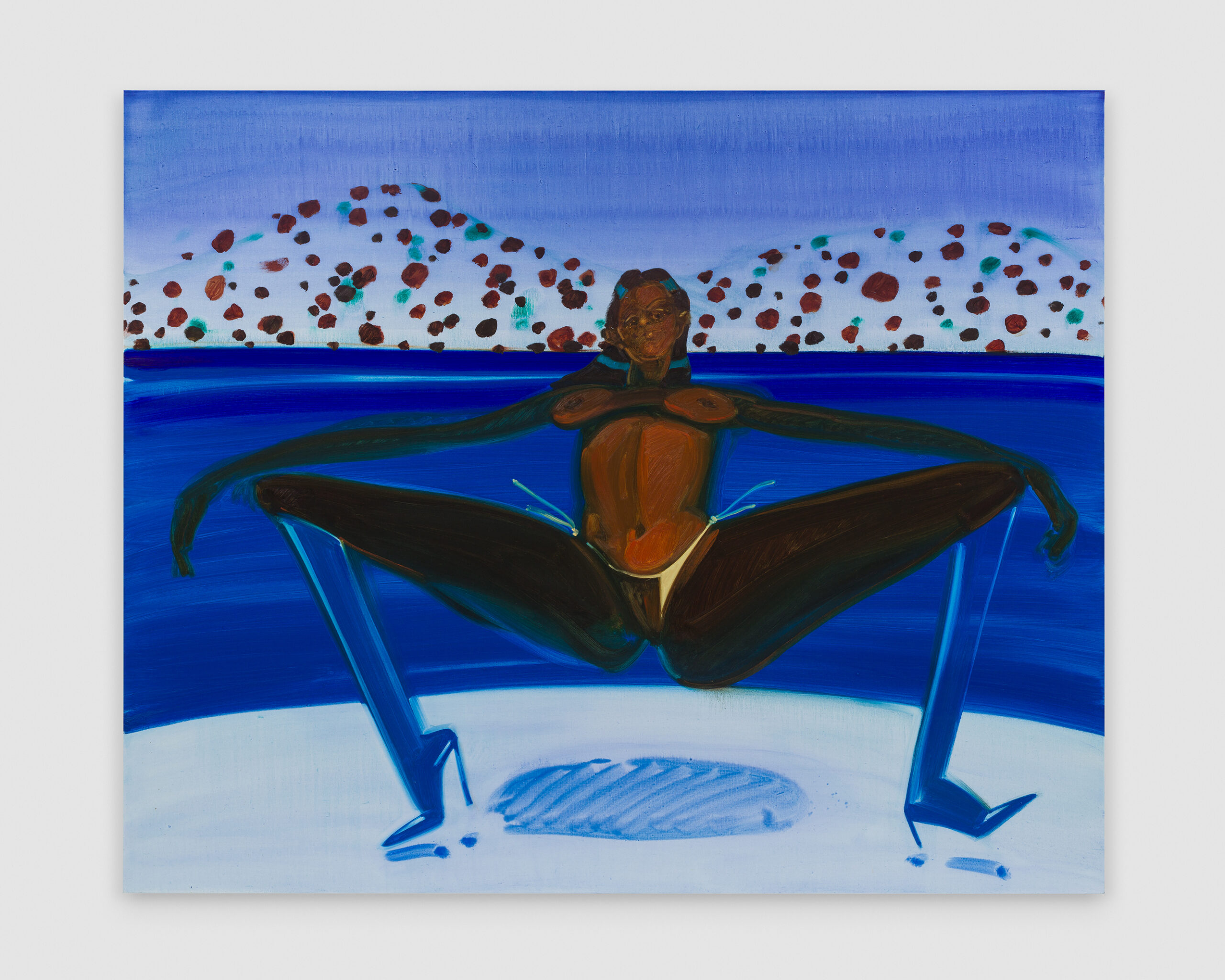

“So much of my work has to do with bodies and fantasies and how they all get tangled together,” Mitsola says, sitting on the floor of her studio in East London, surrounded by bold, bright canvases brought into sharp relief by the late winter grey outside. Since graduating from Slade in 2018, the London-based artist has populated her oil paintings with a cast of otherworldly creatures who live for sensation and sensuality, and challenge the viewer to do the same. Sirens masturbate at the water’s edge, sphinxes wink, and nude figures float through underwater worlds, their bodies soft and voluminous, their sharp eyes staring back at you. Sometimes seductive, sometimes crude, Mitsola’s subjects are “not quite sisters, not quite lovers” and might “kiss you or kill you” if you get too close.

When it came to her latest body of work, Villa Venus: An Organised Dream, which recently showed at Zurich’s Galerie Eva Presenhuber, her focus expanded from the bodies themselves to their surroundings. “I’d been concentrating on my characters for some years, so then I was trying to imagine a place to put them. Where do they sprout from? Where do they live?” she explains. “In 2022, I was on the Greek island of Paros in the Cyclades and it got me thinking about fantastical places. I wanted to create an island of my own.”

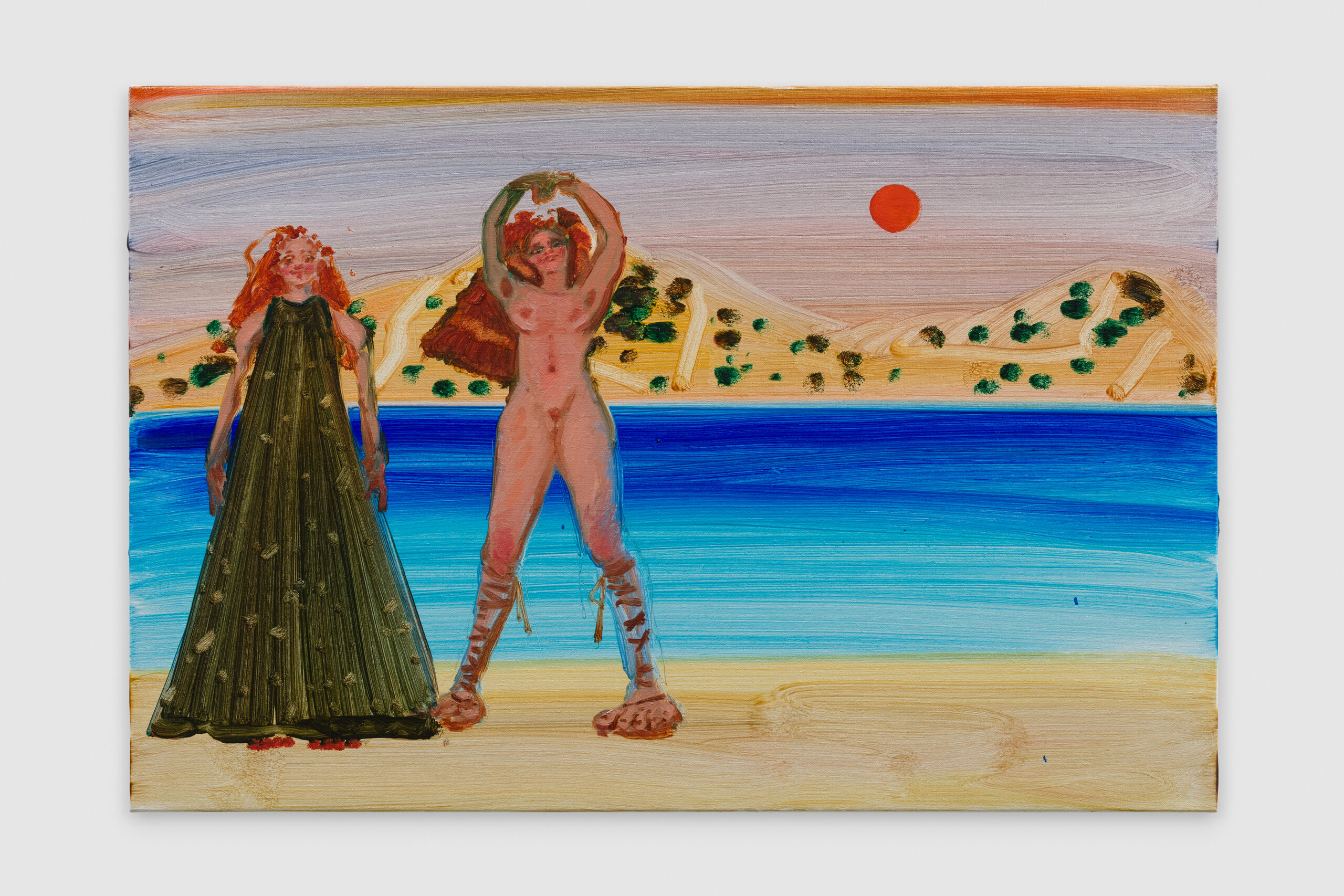

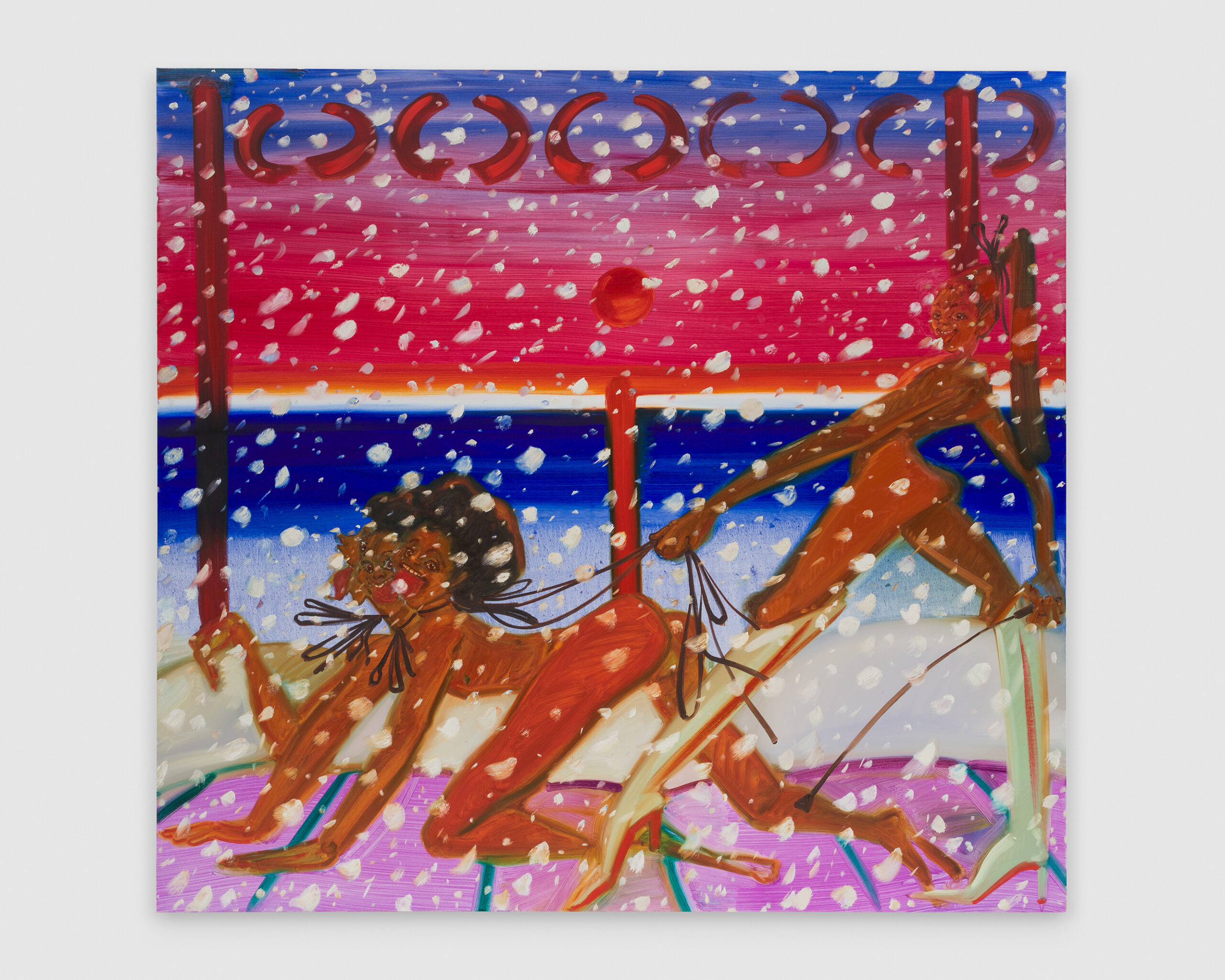

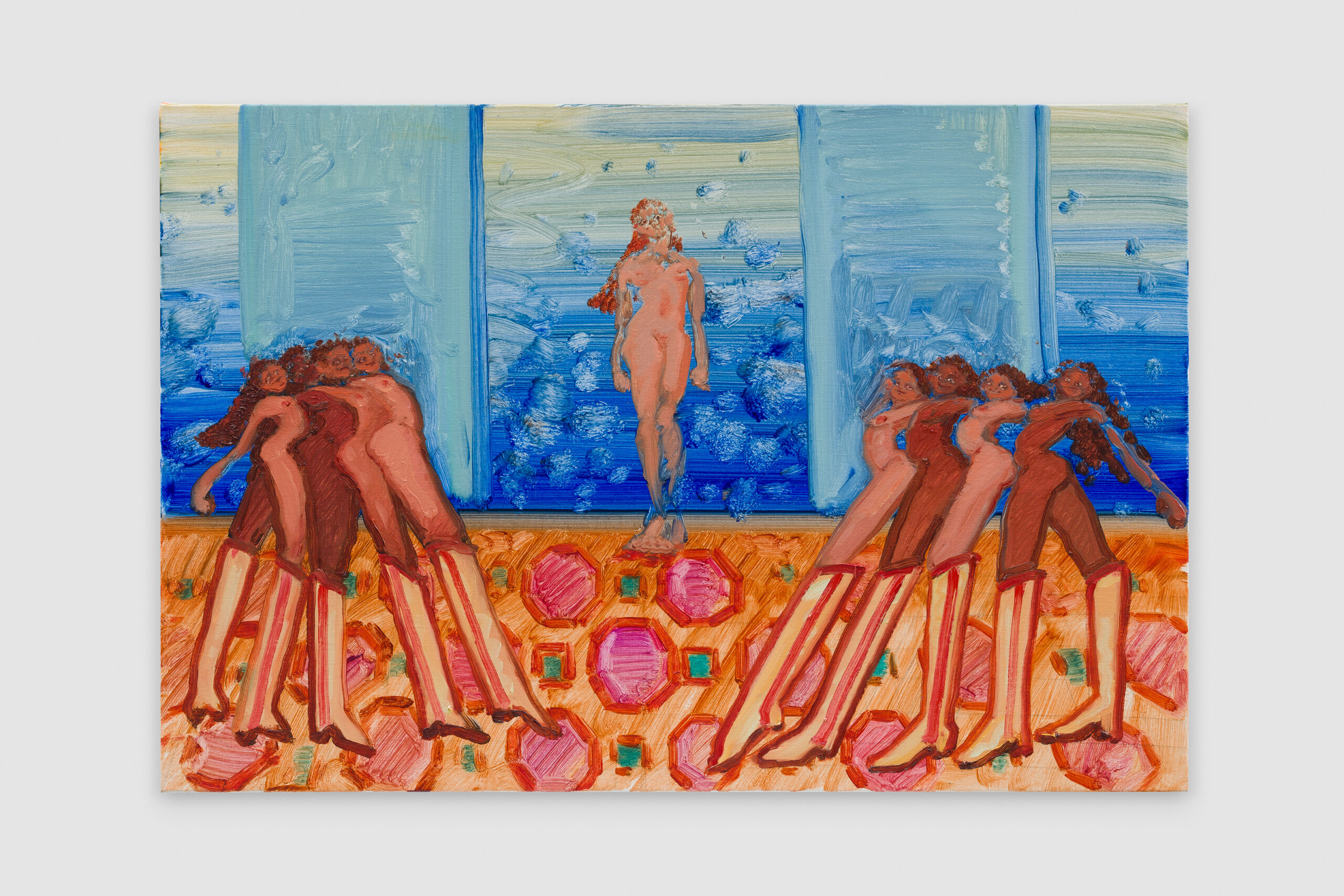

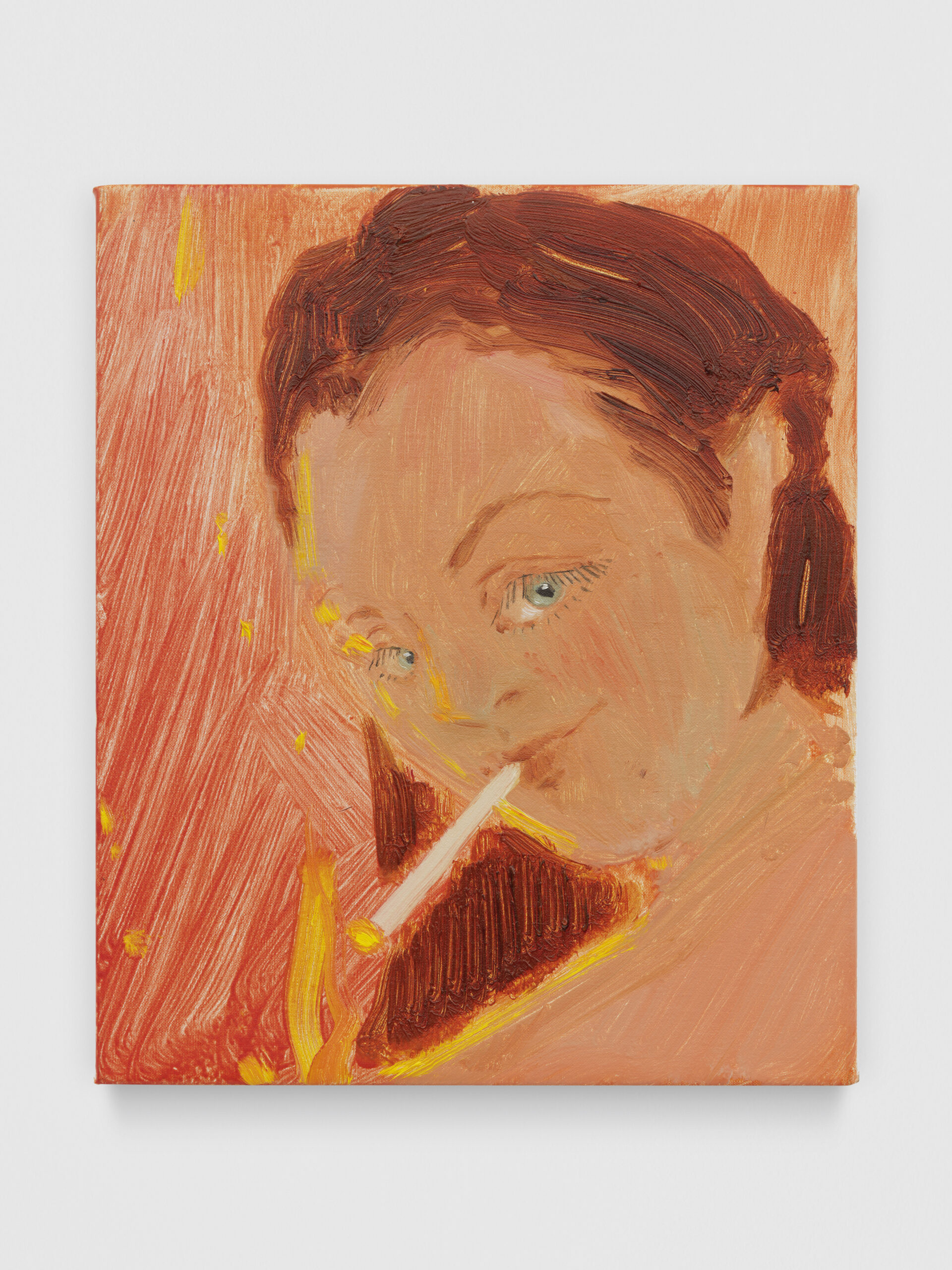

So, in towering oil paintings, Mitsola began mapping out this utopian realm; a Cycladic landscape of flaming skies, piercing-blue seas, and rocky terrain, which feels both ancient and timeless. Envisioning a kind of self-sustaining sapphic society – “like the goddess Diana in her forest grove, or the Amazons, whose society was closed to men” – her characters treat the natural world as their playground. Naked except for thigh-high black boots and neck ribbons, they pee on the hot sand, lounge in the shallows, dance, smoke, embrace their kinks, and pleasure themselves and each other.

Like letting you in on a secret, Mitsola explains that the ‘Villa Venus’ of the collection’s title is not an ode to the Roman goddess of love, but a wink to the fantasy brothel in Vladimir Nabokov’s 1969 novel Ada or Ardor: A Family Chronicle. The story, one of the artist’s favourites, prompted her to consider: “What is bodily freedom? What is sexual freedom?” What it comes down to, she feels, is shame, or the absence of it. It’s why Yorgos Lanthimos’s Poor Things (2023) stayed with her long after watching. “Bella, Emma Stone’s character, lives according to her impulses and desires,” Mitsola says. “She hasn’t been conditioned to feel shame, she’s discovering the world from scratch and letting her body lead. That’s what I want for my characters.”

Tucked into her notes is another literary reference that informs her expression of erotic appetites and attitudes. It’s a quote from Anaïs Nin’s second published work of erotica, Little Birds (1979). “If she laughed then it was the sexual laugh of a satisfied woman, the laugh of a body enjoying itself through every pore and cell, being caressed by the whole world,” it reads. Nin’s words call up Mikhail Bakhtin’s writings on laughter – the way he figures it as a subversive, carnivalesque force that emerges deep within the body and rises upwards and outwards to overturn social norms and hierarchies. This same uninhibited pleasure seems to move through Mitsola’s characters, and also finds form in the natural elements that make up her imagined island.

Themes of fluidity, freedom and transformation are explored through the motif of water, in particular. Having spent every summer since childhood snorkelling in the Aegean, Mitsola feels a deep personal connection to the sea. “There’s something so magical about it,” she says. “This sense that when you enter it you’re entering a different world, that you can feel your body become part of it.” Dreamily, she describes the metamorphosis that takes place at both a physical and a subconscious level when submerged in watery depths. The way hair splays out “like a jellyfish or a Medusa”, the way your edges seem to dissolve. “Your body is lighter in the water – it lifts you up and sort of liberates you.”

As inspired by astrology as she is by mythology, Mitsola admits that she casts her creatures according to the signs of the zodiac. “I think my paintings would be fire or water signs, completely opposite but both very powerful,” she muses. “Water is a quieter, more transformative power, and fire is like bursting with energy and readiness to act.” (A quality she recognises in herself, as an Aries.) When planning her paintings, she thinks in terms of these elements, and how they translate into temperature and colour. Some works are “hot like the sensation of walking on burning sand”, others are “cool like a refreshing plunge in the water”. This collection was the first time she experimented with translucent colours, a means of creating “very bright paintings that project light outwards”.

At more than two or even three metres tall, these are also the largest paintings Mitsola has ever made. Working at this scale enabled her to move dance-like around her studio, mark-making with big brushes and natural fibre brooms. “My paintings are very performative,” she says. “I wanted the viewer to feel traces of my body moving around the canvas. And I was looking at theatre and ballet sets, thinking about how to paint backgrounds that reflect the personalities of the performers.”

Mitsola’s references are kaleidoscopic. Her gaze flickers between Ancient Greek caryatids, Edvard Munch’s nudes, Art Nouveau design, and “visual spectacles” like Jacques Offenbach’s 1951 opéra fantastique The Tales of Hoffman; from a print by 19th-century Japanese artist Utagawa Kuniyoshi (“The falling rain feels like streams of energy,” she scribbles next to it), to Mia Khalifa’s bikini pics. And beyond Nin and Nabokov, literary works like Virginie Despentes’ King Kong Theory (2006) and Olivia Laing’s Everybody (2021), both concerned with questions of bodily and sexual autonomy.

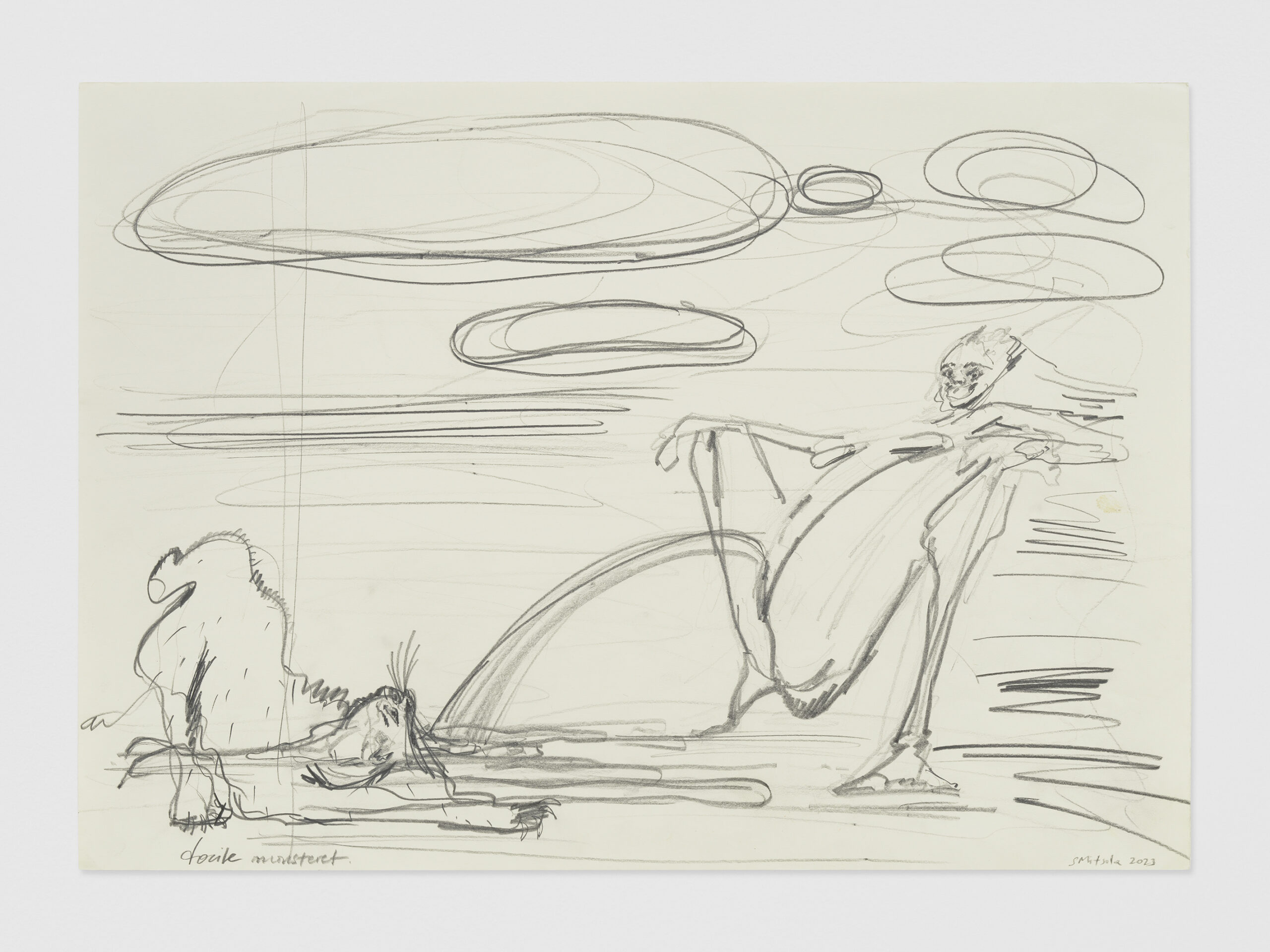

Mitsola also delved into different approaches to worldbuilding in fantasy fiction, gaming, and animation, and found herself drawn to the softer end of the spectrum. “I really like this idea of soft worldbuilding, like when you build a world or a mythology but you don’t have all the details ironed out,” she explains. “You don’t give the viewer everything, you leave some things to their imagination.”

She references filmmaker Hayao Miyazaki, co-founder of Studio Ghibli, who focuses more on the emotional and aesthetic quality of his stories than the stratification of his imagined societies of gods and spirits. “I prefer his approach to the hard worldbuilding of J.R.R. Tolkien,” she states. “With Tolkein, there’s an answer and an explanation for everything. There’s not so much room for interpretation.”

Mitsola’s own myth-making extends from her canvases to the creation of textual artefacts. Her recent publication, Book of Aquamarina (2024), chronicles the adventures of two characters from her earlier paintings – sisters Aqua and Marina. As she writes in the foreword, these “large semi-aquatic predators” are “the closest living relatives to the Egyptian Sphinx and the Aegean Sirens”, and rise to folkloric fame for brutally attacking a Nile crocodile in their quest for power and territory.

Pencilled text and sketches, watercolour vignettes, and gold leaf ebb and flow across the parchment-coloured pages of this A3 book, styled as “an exact copy of the original manuscript, now long lost, and the only surviving source of the myth of Aquamarina”. Its unfinished, fragmentary feel and use of blank space does indeed leave room for the reader’s own questions, answers, laughter, and surprise.

The publication is testament to Mitsola’s delight in crafting fantasy worlds and darkly comic narratives that spill out across different disciplines. Throughout her practice, there is a sense of the uncontainable. Paintings that practically glow with Cycladic light and heat and passion. Exuberant figures that fill the frame to the point of breaking free from it. Her playful approach to worldbuilding touches on the second sleight of hand in the title of her latest collection: the ‘organised dream’ of Villa Venus: An Organised Dream.

“It goes back to this question of how do you organise a utopia, how do you organise a dream?” Mitsola says, smiling at the paradox. “Well, you can’t organise it too much because if you do then it becomes something else. Too much control and it’s not a utopia at all.”

Written by Madeleine Pollard