Since 2009, archivist and found-photography artist Thomas Sauvin has amassed a collection of more than 850,000 photographs taken in the Beijing area, collecting negatives by the kilo from an illegal silver-nitrate depot and restoring them to life to reveal a previously unseen social history of China—by and of the people—in tandem with the introduction and proliferation of analogue photography from the mid-80s. In 2012, Sauvin began to cull images that repeat thematically across the archive and turn them into series.

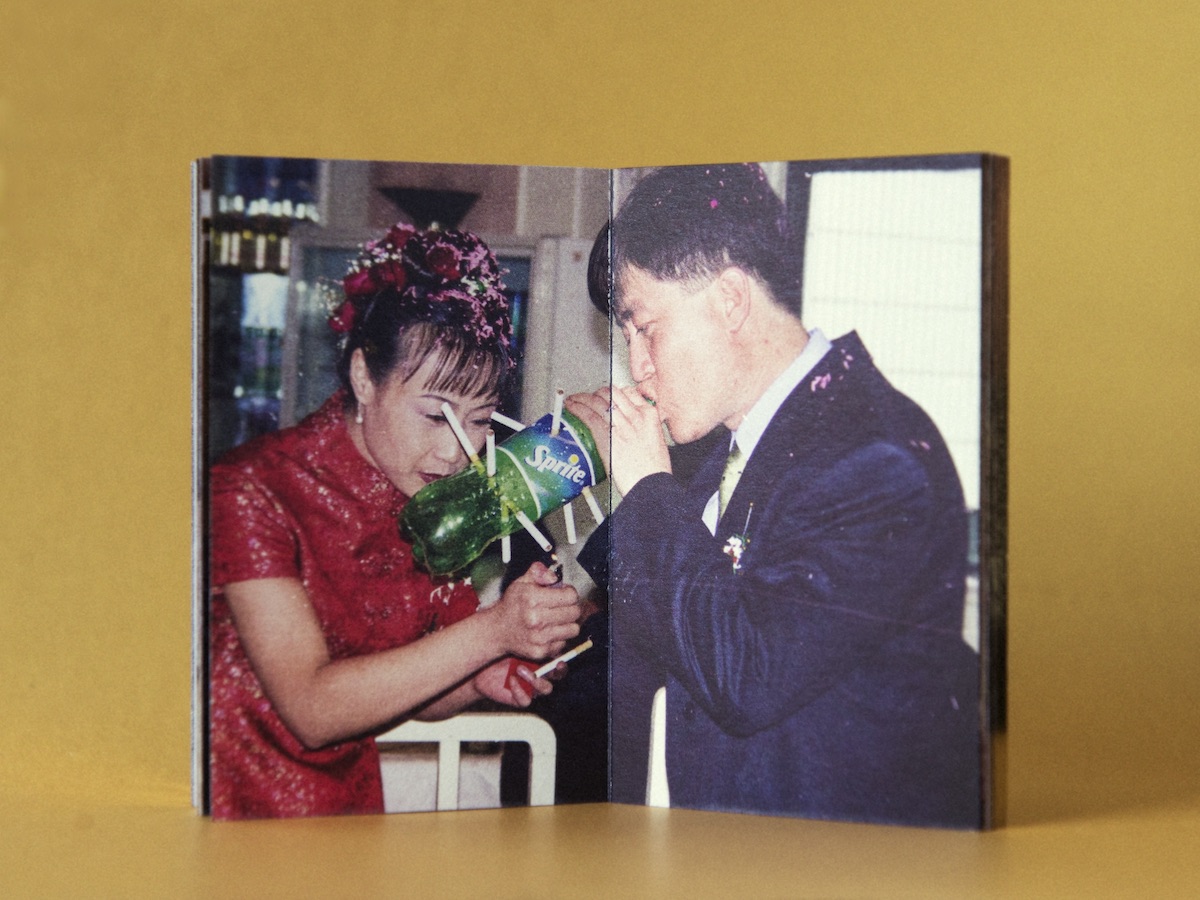

One of them, which he’s entitled Until Death Do Us Part, gathers portraits of a very unusual modern Chinese tradition: smoking at weddings. “I started to go through the entire archive and focus on the wedding photos. It was very hard to find any wedding photos without cigarettes. It brings focus to a tradition that the Chinese had forgotten about—and that wasn’t yet known in the West. I thought it was a good thing to show,” Sauvin says. Taken by anonymous, amateur photographers, perhaps most of them guests at the wedding, the imperfect images are a glimpse into the customs, fashions and family life of China during a time of major social and economic reform, as China opened up to the West. It’s a period in the nation’s history that is usually defined by images of the Sino-Vietnamese conflict or the Tiananmen Square protests. In Sauvin’s document, Red China is interpreted differently, by way of the red of a wedding dress or of the cigarette boxes.

“Having attended Chinese weddings, I had seen myself that cigarettes were absolutely everywhere. The only phenomenon I really couldn’t explain was the Chinese wedding bong. When I had about six different images of newlyweds smoking a wedding bong filled with tens of cigarettes, I posted them on Weibo [the Chinese Twitter] to see how people would respond. Soon someone explained that these were usually prepared by the best friends, schoolmates or university friends of the bridge and groom as a ‘funny’ torture for their friend.”

“In Sauvin’s document, Red China is interpreted differently, by way of the red of a wedding dress or of the cigarette boxes”

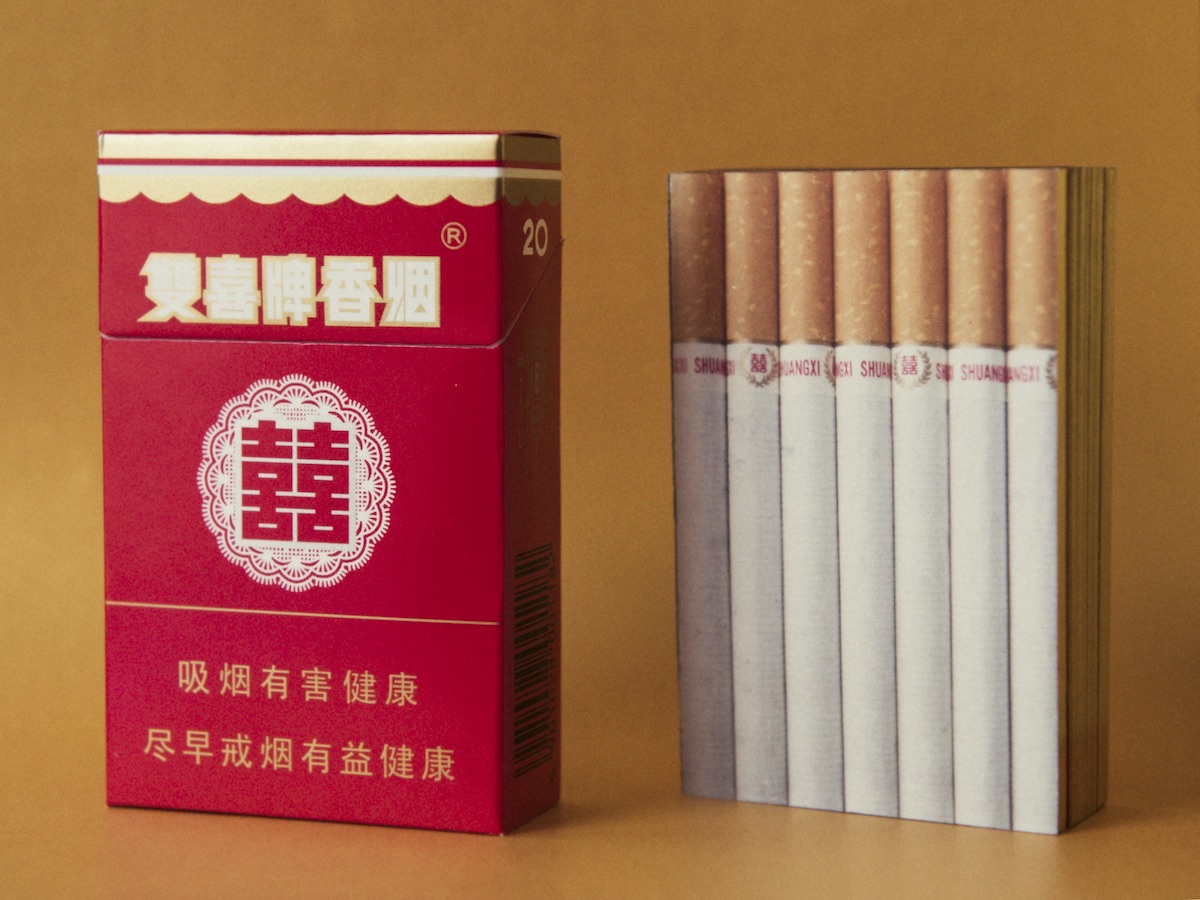

Cigarettes made by Double Happiness, one of the oldest and most influential tobacco brands in China, are offered at weddings because of the lucky combination of characters in the name, symbolizing longevity and love for the newlyweds. The irony hasn’t passed Sauvin by, but then again strange things happen at Chinese weddings—as a photograph of a baby with a cigarette in his mouth, held proudly by his mother, suggests. When Sauvin decided to produce a publication of the smoking pictures, it seemed obvious that the book should be designed to fit inside a real pack of Double Happiness. Sauvin approached the brand to collaborate, but they declined, concerned that handing out boxes of their tobacco with a book inside might disappoint their customers—or that the boxes might be used to carry fakes. Instead, Sauvin wound up buying hundreds of packets of the cigarettes and emptying them out himself. “I had sixty thousand cigarettes in my studio. I had quit smoking about two years before that, but suddenly surrounded by sixty thousand cigarettes, I very quickly started smoking again.”

He couldn’t smoke all sixty thousand, though, and was confronted with the unanticipated problem of getting rid of them—harder than you might imagine. A certain quantity was distributed to the printing factory where the book was produced, who organized a free dispenser for its workers. “Some foreigners come to China and make sure that families have money so their children go to school. I guaranteed people would have cigarettes.” Another three thousand were used for an installation at the Central Academy of Fine Art as part of the 2015 Beijing Photography Biennale. “The images were shown in a tailor-made, three-metre-high pack of Double Happiness cigarettes, where you could also find a wedding bong, a stinky ashtray and a few thousand cigarettes, free to take away.”

“I had quit smoking about two years before that, but suddenly surrounded by sixty thousand cigarettes, I very quickly started smoking again”

The Until Death Do Us Part images received a warm response both in the West and in China—which, as Sauvin explains, is rare, revealing the clash between how China is depicted through photography outside and inside the country. “Foreigners have a passionate relationship with China. There are two extremes: the ones who love China for calligraphy, for tea, for mountains, and the ones who hate it, and are obsessed with corruption, pollution, Tibet and Ai Weiwei. It’s a very extreme way to depict China but this is the image of China that’s imported to the West. It dehumanizes the country and the people.”

With this series—alongside five other publications that he has created from the archive to date—Sauvin gives us another version of China, one that was never intended to be shared so widely. It tells the story of the birth of contemporary China according to the people, not its department of propaganda. At the same time, there’s a universality about the theme, which isn’t really about smoking, but about union. “When dealing with found footage, it is usually a person’s story that is being told. I guess I liked the idea that a forgotten ritual could bring anonymous images together. I am a big smoker myself, and I usually hate wedding images as they usually try and fail to show love and happiness. For all these reasons, making this book perfectly made sense. I believe the reason for the positive reactions in China and the West may be because it’s an unusual angle from which to portray the life event that a wedding is.”

“When dealing with found footage, it is usually a person’s story that is being told. I guess I liked the idea that a forgotten ritual could bring anonymous images together”

There’s also a special subtext to Sauvin’s series that is more personal to the archivist: addiction. The French-born photography fanatic continues to collect images from Beijing, at the rate of around nine thousand a month. It’s a costly, labour-intensive operation that involves sourcing the negatives and selecting those that can be reproduced and scanned, before the images are returned on a hard drive, organized and added to the archive. But he’s not ready to quit just yet.

I ask Sauvin if there is any image he’s particularly drawn to among the wedding pictures. His response reveals, perhaps, the magic that motivates him to keep trawling through these abandoned photographs. “There is one image I really like which is quite easy to miss when you go through the book. It’s a photo of a woman blowing smoke in her future husband’s wide-open mouth. They are very blurry as the focus was accidentally made on the wallpaper in the background. It’s hard to understand what is actually happening but the only thing we are sure of is that they’re having one hell of a good time.”

Images from and of Until Death Do Us Part, courtesy Jiazazhi and Thomas Sauvin

This feature originally appeared in Issue 30

BUY ISSUE 30