As a graduate of one of the only drawing degrees left in the country, you would expect that my understanding of this medium might be a little more straightforward than it actually is. In fact I find it confusing, elusive and incredibly frustrating.

This is due in a large part to the fact that I did very little drawing during my three years’ studying. After a poor showing at term one’s life drawing classes they were cancelled entirely, to the upset of those of us who really enjoyed going and felt, perhaps naively, that life drawing should be guts of a drawing degree.

Only one person graduated with drawn works, the rest of us played around with televisions, installation, found objects; myself with pinhole cameras. The problem was, no one seemed to have even a loose definition of drawing — sketches on paper seemed preparatory, intense pencil works of objects from life or imagination seemed illustrative. There was little to no mention of the possibility of digital drawing, favoured by young artists such as Bunny Rodgers, or automated drawing, seen in the works of Rafael Lozano-Hemmer. We knew many things that drawing wasn’t, but very little that it was. I left with the strict impression that drawing had died a death.

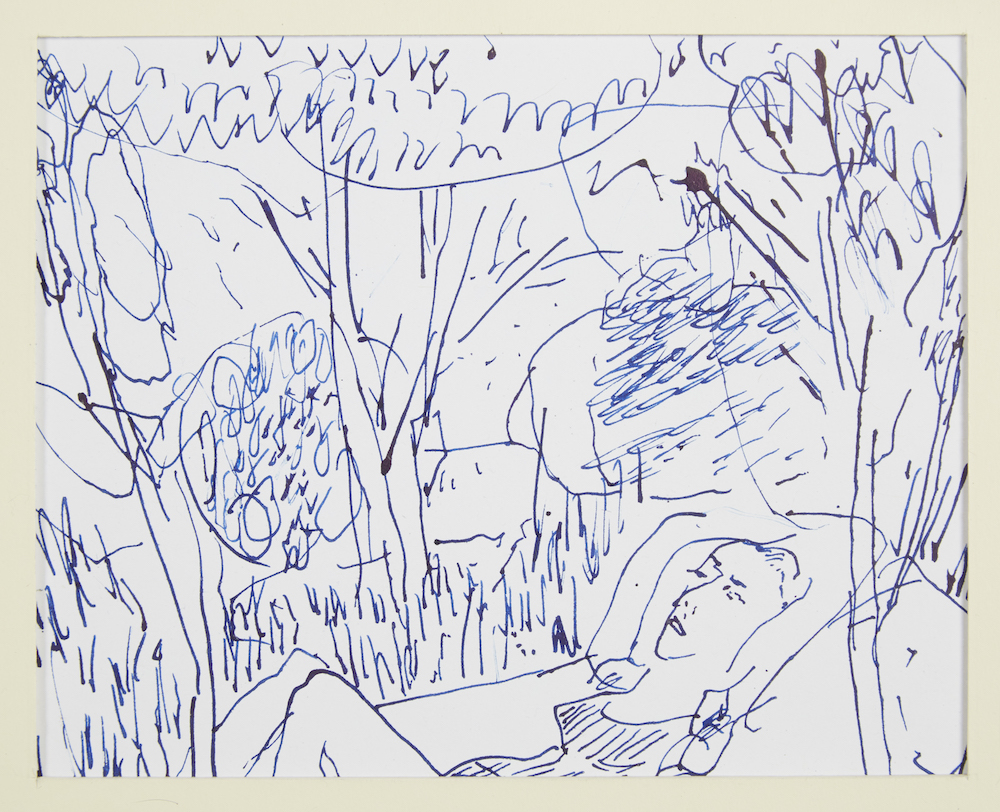

As I’ve spent time around visual art since, around artists of different ages and disciplines, I’ve found the medium popping up in many unexpected places and with many different hats on. It is by no means a simple medium, and it has certainly been required to divorce its history in some sense to really move forwards — as have all the others. But although the history of pencil or pen on paper has many strict conventions and rules to it, it feels reasonable to expect that this tradition can be shaken off without getting rid of the tools entirely.

Drawing, when it has cropped up recently as a big thing — in the large fairs and prizes it is often pretty absent — has tended to have a live element to it, and also a slightly throwaway nature. David Shrigley brought the life room to 2014’s Turner Prize, though the drawing itself took second place to the NSFW sculpture that sat centre-stage. The drawings produced had a decidedly sketch-and-go quality to them. Similarly, Ken Kagami kept crowds amused for days on end at Frieze London 2015, drawing 20-second works of men’s genitals and women’s breasts — strictly from Kagami’s imagination you understand, though, we have to say, team Elephant’s were spot on. Again, these works and the setup offered a non-serious view of the art form, producing mass results that were intended as light-hearted offerings for the passing crowds.

Then, of course, there are the new innovations which take into account everything that drawing is and can be, while pushing the conversation forwards. The digital has changed a lot in drawing. Microsoft Paint allows for a bridge between man and machine, which artists such as Rogers like to make the most of. The hand of the artist is still present, the line is still controlled by the artist’s intention, but the output has something of the new to it. Automated drawing machines allow for a room, a crowd, or another external element to take charge of the entire output, the machine responding to factors entirely outside of the artist’s specific ideas.

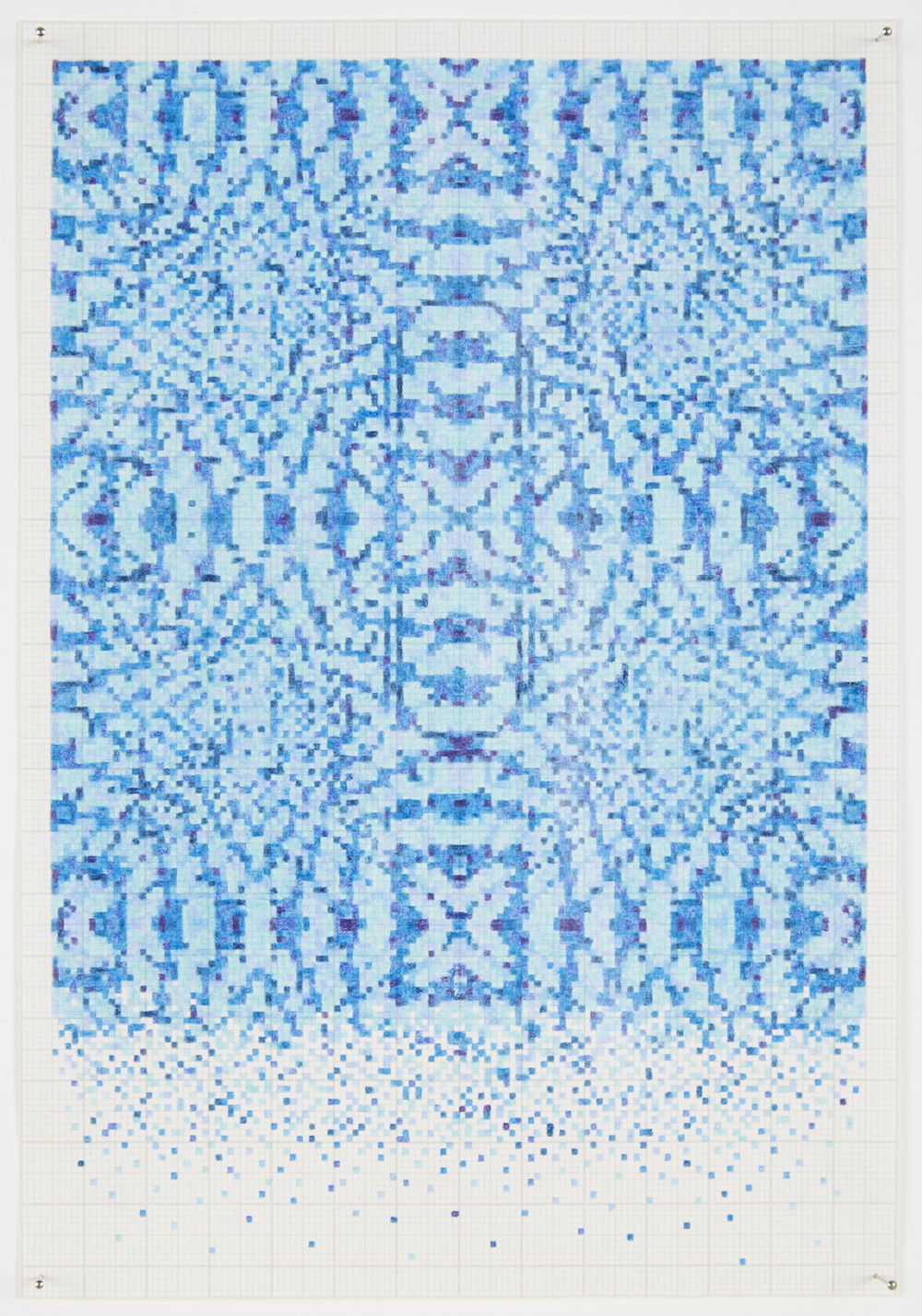

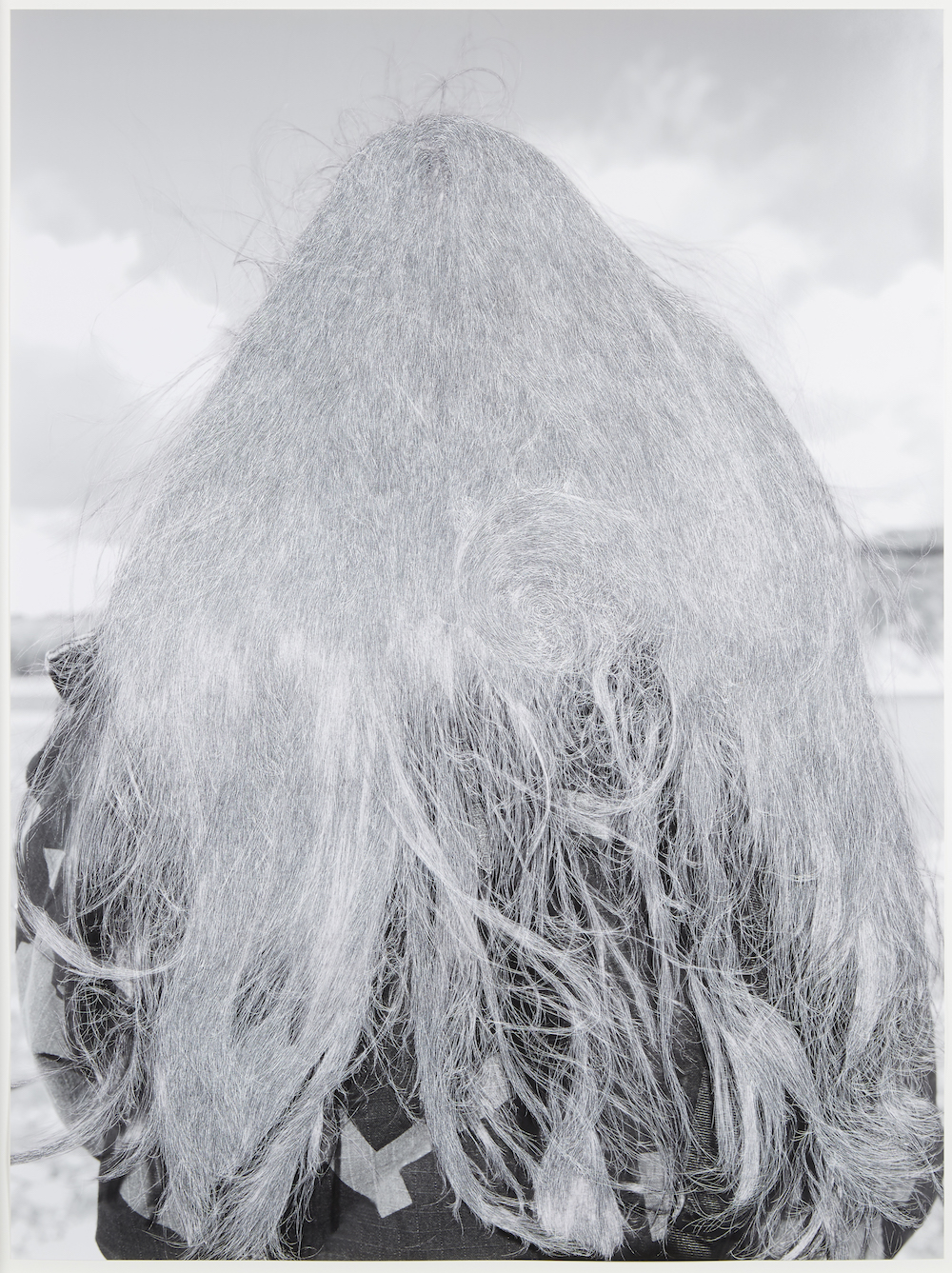

Take a simple approach to the relevance of drawing and you may deem it obsolete. Take into account the many possibilities left untouched and the medium opens right up. Every year, London’s Jerwood Visual Arts hosts the Jerwood Drawing Prize, a fantastic opportunity to discover new ways of approaching drawing, and for enjoying more conventional practices also. I spoke to Anita Taylor, Dean of Bath School of Art and Design and Head of The Jerwood Drawing Prize as the judges entered the first selection process for 2016’s prize, which will show from 14 September at the gallery. Personally, one of the most exciting things for me in seeing the shortlist for the prize each year is quite how many of the artists still use simple tools — graphite and coloured pencils, pens — to make work that feels totally contemporary.

What is the main incentive for Jerwood Drawing Prize to exist? Is it about getting more artists drawing or celebrating those who already do?

The Jerwood Drawing Prize started life as an open exhibition dedicated to drawing in 1994 (with Jerwood Charitable Foundation later becoming the principal sponsors). The open exhibition has an overarching aim to genuinely affirm the value of current drawing practice through the exhibition of new drawing-based work. As an open submission exhibition, it extends the opportunity for the unknown — both drawing makers and drawing practice — to come to the attention of a diverse panel of experts, and then to engage with a wider audience and participate in dialogue through the annual touring exhibitions. Today, there is much more demand for this opportunity by a wide range of artists, with over five times as many artists submitting new drawings for the Prize than when we began. The project is a successful model in promoting the activity of drawing to artists at all stages of their careers. The number of student winners and exhibitors over the years testifies to that as well as those who have a longstanding and committed drawing practice. We celebrate drawing.

How has the nature of drawing as a medium changed since you began working in the art world? Do you feel its place has changed amongst the other mediums?

I believe that drawing has become more prominent as a discipline in its own right, and has been re-positioned as an integral means of developing ideas within creative practice, and importantly, the discourse surrounding drawing is now deeper, more focused, and reaches a much wider audience. The technology of drawing has extended – the means of making drawing – as has the dialogue about it.

Are you noticing any new approaches to drawing coming through in the entries over the last few years?

Not unexpectedly in the present moment, there are more digital drawings, however, I believe a resurgence and attention to the hand drawn, to touch and the sensual and to the possibilities of drawing as a visual language have also extended. The incredible range of possibilities of this flexible language and discipline are tested by highly motivated and imaginative artists and new ideas and insights come to the fore each year.

What is drawing to you?

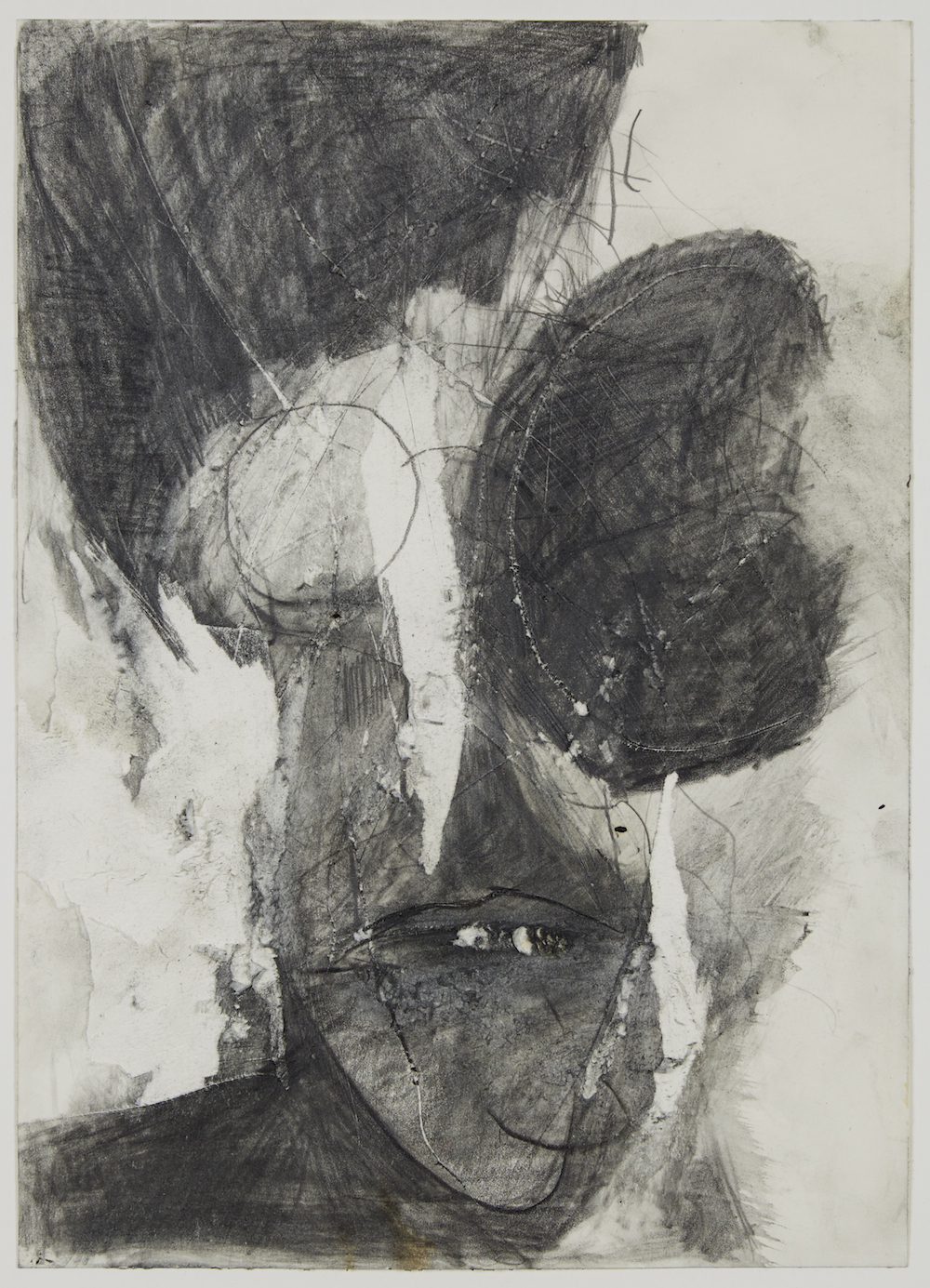

Drawing is a fundamental means to understand and to interrogate the world, and through this very visceral, physical process, it becomes clear I am interrogating my world; through drawing I see what I am thinking and gain understanding of what I am experiencing. I also simply enjoy the energy and flow of visual discovery and connections that drawing facilitates. Drawing is a daily constant for me; and the capacity of drawing to distil and convey experience as a phenomena is compellingly human in both its physicality and imaginative impact on me.

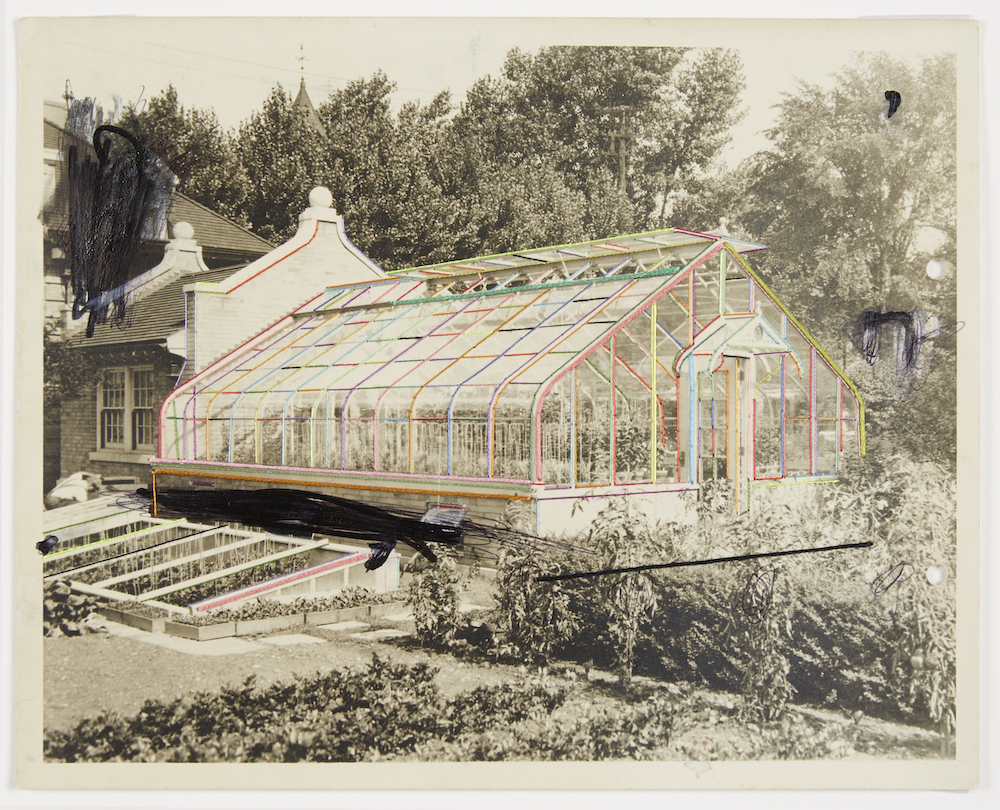

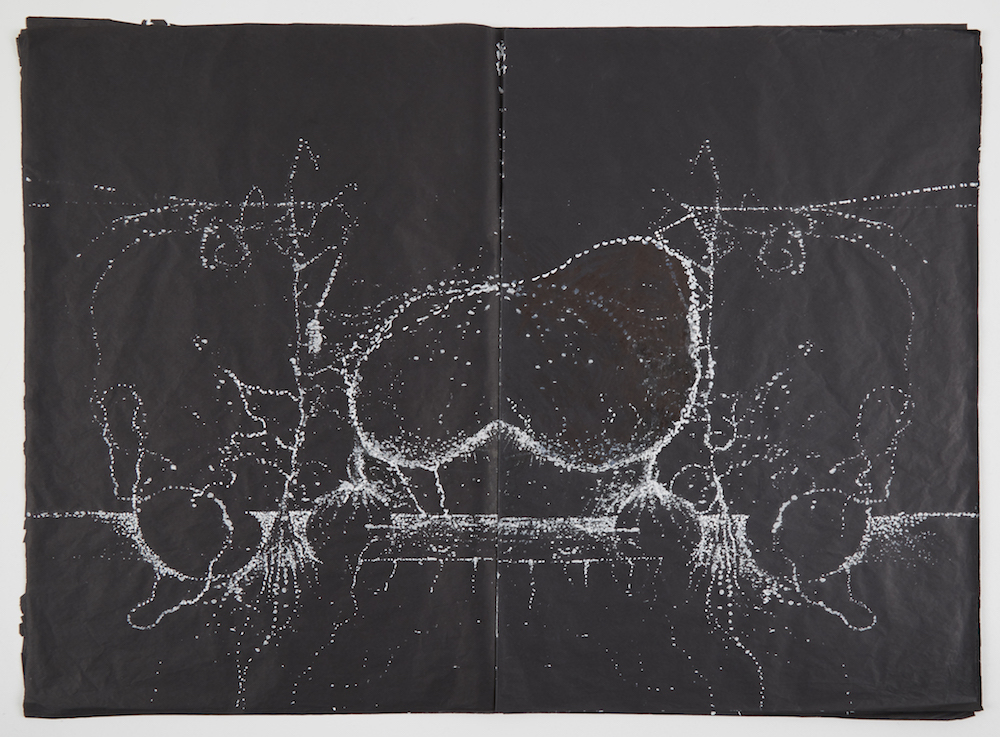

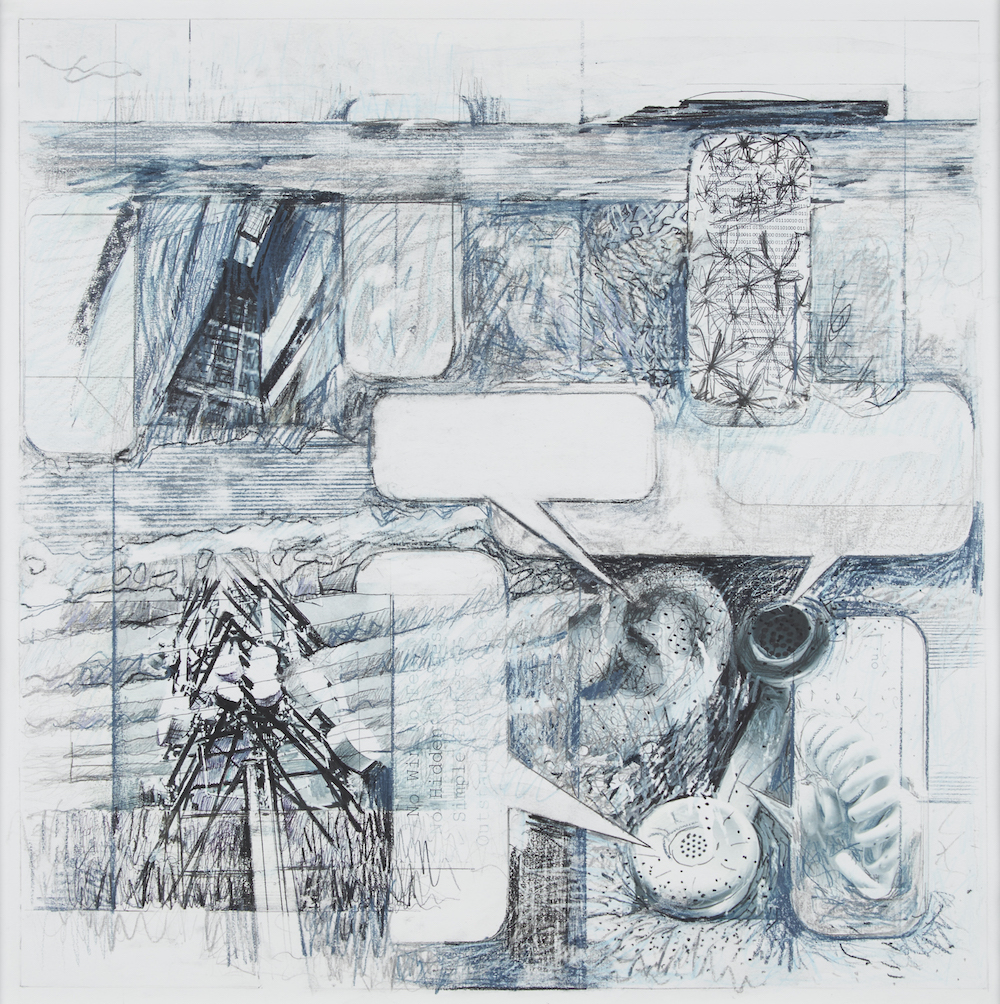

Exchange + Draw, Crank Call, 2015 Pencil, mixed media on digital print, 57 x 57cm