“In the mornings, which had once throbbed with the dawn chorus of robins, catbirds, doves, jays, and wrens, and scores of other bird voices, there was now no sound; only silence lay over the fields and woods and marshes.”—Rachel Carson, Silent Spring (1962)

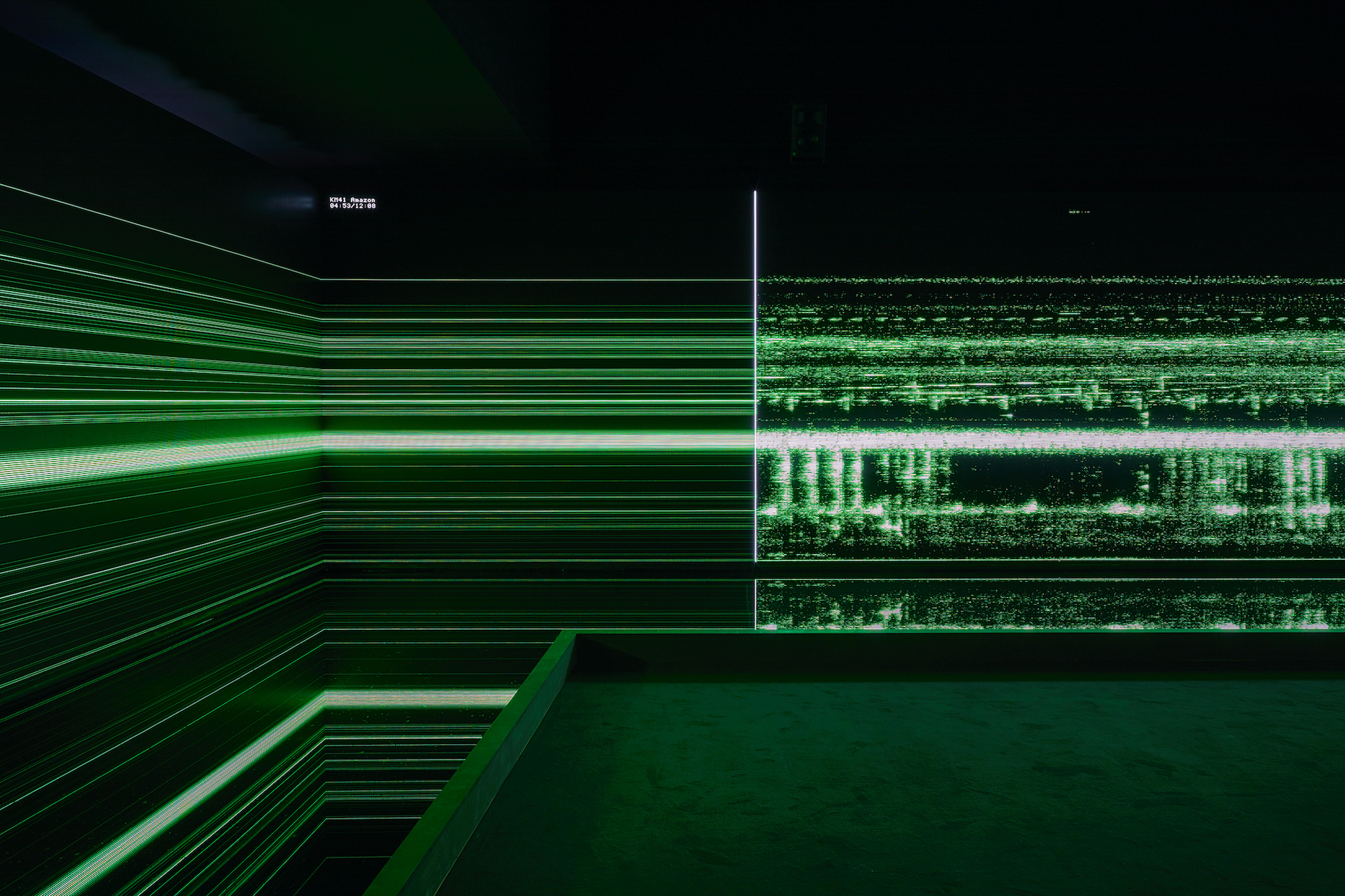

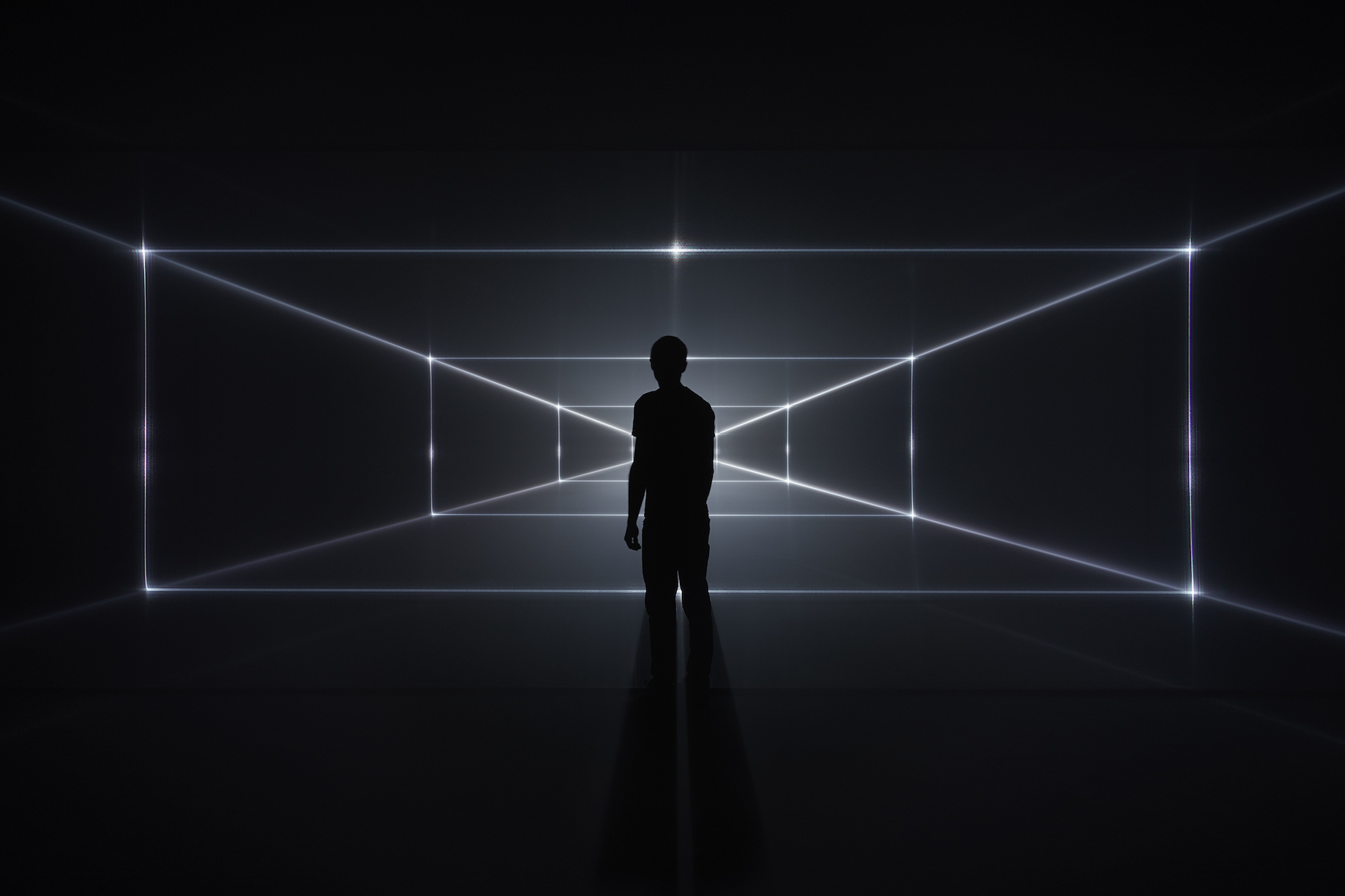

Neon blue lines pulsate across the expansive walls of a blackout room in London. Caught somewhere between Matrix-style graphics and the heartbeat visualized by an electrocardiograph (ECG) machine, the lines are jittery and half disintegrated, shuddering to the sound of birdsong. The calls of countless species fuse together as the tempo builds: it’s the sound of thousands of birds making their annual pilgrimage to the Yukan Delta of Alaska to mate—the sound of life itself—recorded by the American musician Bernie Krause in 1993.

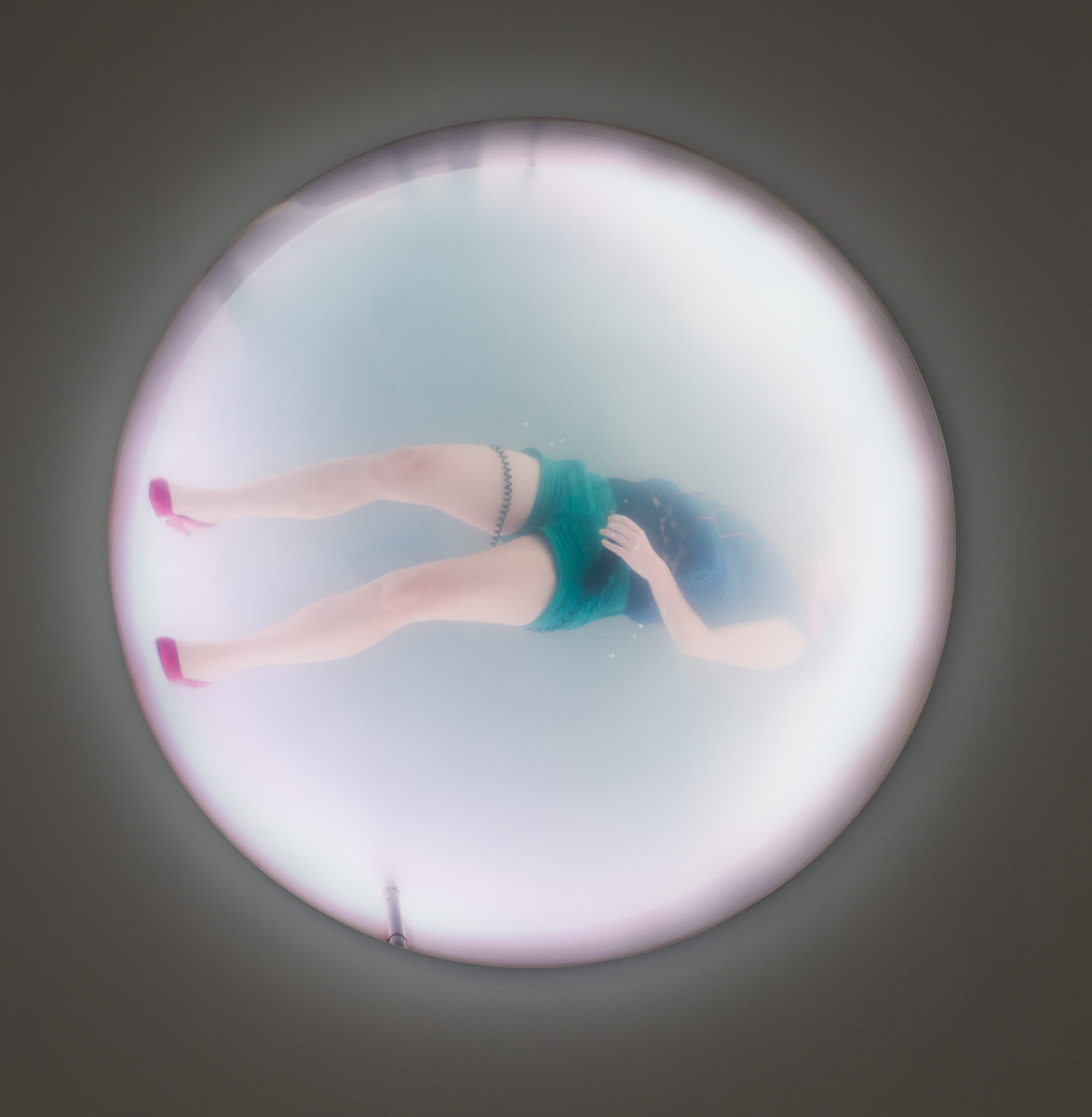

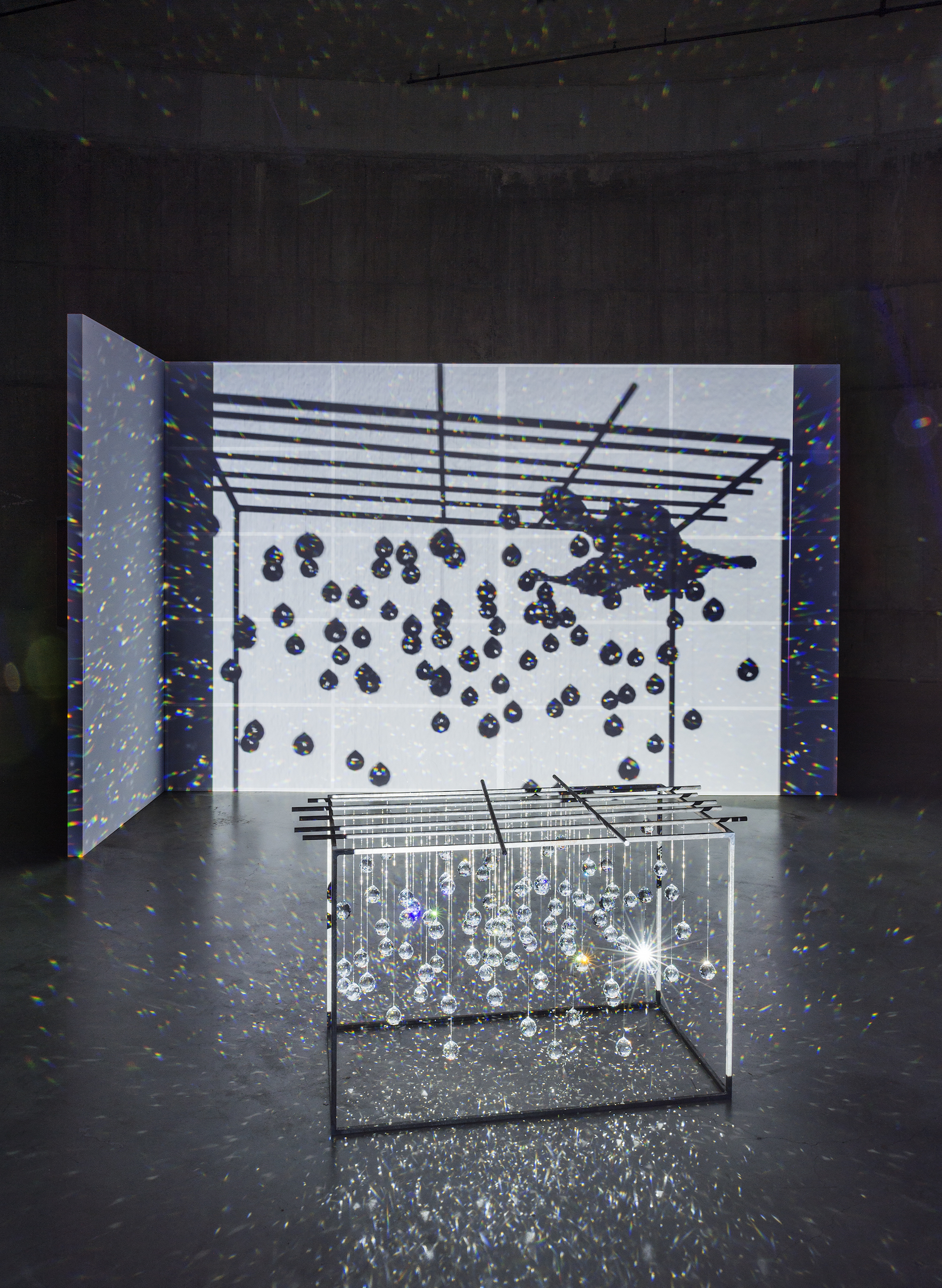

Installation view of Our Time, United Visual Artists. Other Spaces at The Store X 180 the Strand 2019. Photo by Jack Hems

Like the life-affirming beep of an ECG machine, The Great Animal Orchestra (2016) at 180 The Strand feels comforting at first. Slumped in a beanbag in an empty brutalist building turned annual art mecca in London, during the high heel clacking, taxi horn blowing, champagne cork popping soundscape of Frieze week, Krause’s hypnotic nature recordings are a welcome respite. Jacked up into an immersive environment designed by the London-based experience gurus United Visual Artists (UVA), The Great Animal Orchestra is an edenic parallel world of sensory stimulation, where the cries of animals signify a thriving planet.

“The Great Animal Orchestra is an edenic parallel world of sensory stimulation, where the cries of animals signify a thriving planet”

That is, until everything goes quiet. Amid the 5,000 hours of dramatic and invigorating audio recorded by Krause over the last fifty years—an epic odyssey which took the musician, now eighty years old, to far-flung field sites including the Amazon, Zimbabwe and the Arctic tundra—the creaturely symphony is punctured by the sound of silence. Far from a doctored tape, Krause simply returned to the 2,000 odd habitats he visited from 1968 until now, and recorded what’s left of the 15,000 species—about half of which no longer exist.

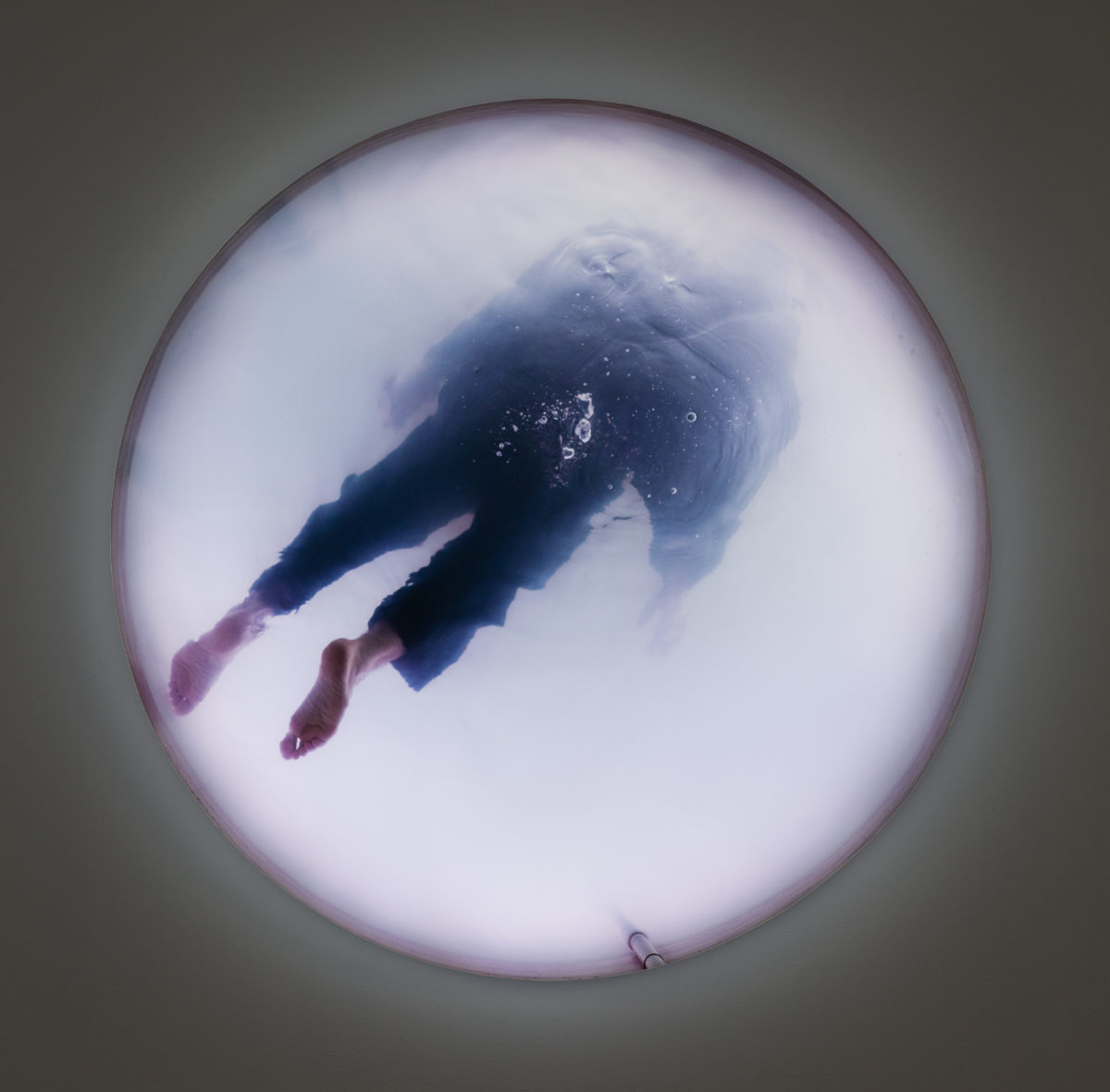

John Akomfrah, Still from Purple, 2017 © Smoking Dogs Films and Lisson Gallery

In our image-saturated culture, sound hits harder than visuals. Occupying a deathly still black-out room that had mere seconds ago been populated by a carnal crescendo of animals is a thoroughly disturbing and alienating experience. It makes mincemeat of your own existence, which seems so brief and irrelevant in the face of the orgiastic life-bomb that just ghosted you, leaving you to awkwardly shift in your scrunchy polystyrene seat, flanked by strangers, waiting. This anxious feeling cuts deeper than any image of a burning rainforest or melting icecap—horrific imagery that has been declawed by its ubiquity on your feed, the morning news, and so too, contemporary art.

Of course, artists have been addressing climate change for decades (way before their scientific counterparts). Artists, being artists, have a knack for crafting narratives that are more absorbing and damning than the flurry of apocalyptic news stories and dense ecological reports. Some do this by splicing explicitly disastrous man-made environmental meltdown with sprinkles of the miraculous, creating a weird cocktail of emotions that slams you with guilt for feeling hopeful and makes you feel depressed when you ought to be inspired. In other words, it temporarily extracts you from your humanity so that you might judge the severity of the so-called “anthropocene” from a non-anthropocentric perspective.

- John Akomfrah, Stills from Purple, 2017. © Smoking Dogs Films and Lisson Gallery

I’m thinking of John Akomfrah’s monumental six-channel video installation Purple (2017), which premiered at the Barbican’s Curve gallery two years back. As the camera pans over sublime arctic landmasses and scraggy volcanic islands in the South Pacific, the classical score swells in anticipation; you half expect David Attenborough to emerge from the tundra to deliver a slice of arresting commentary. But any celebratory element quickly melts away as the screen flicks to an ominous figure in a hazmat suit who stares out into an empty ocean. It’s the film’s constant tug of war between disaster and desire that keeps you enraptured, so desperate for a palliative happy ending, looking for a lighter salvation from the looming disaster narrative.

“In our image-saturated culture, sound hits harder than visuals”

At the movies, we have adopted a sweeter tone of redemption where the idea of an impending planetary crisis is a reversible destiny, something that can be undone with human grace and tenderness. Interstellar (2014), The World’s End (2013), and American rom-com Seeking a Friend for the End of the World (2012)—which posits the salvation of a dying planet is achievable through romantic spontaneity—are cases in point, where ecological destruction is reduced to an anthropocentric metaphor for our own troubled relationships, both political and personal.

In more recent times, where the severity of our climate emergency has become popular knowledge yet remains off-limits talking points to most politicians, it bubbles up in cameo within the superhero genre. Movies like Predator (2018), Venom (2018)—whose Elon Musk-like villain dreams up a future human race made stronger through alien DNA—relegate the issue as an abstract plot point, an aside to the main action. Even in films where the topic is more central, such as Marvel’s Avengers: Endgame (2019), which picks up current issues of resource scarcity and overpopulation, climate change is still protracted as a futurist sci-fi condition, not something to be dealt with in the here and now. The exception is Black Panther (2018), a film that finally brings race into the equation, as the seeds of climate change were sewn by an industrializing western world, to offer ecological sustainability as an afrofuturist manifesto.

Artists, too, reach toward the mystical and cinematic as a generative way of addressing climate change. In 2010, Joan Jonas performed Reanimation for the first time at MIT, in collaboration with musician Jason Moran. Jonas, now eighty-eight, traipsed around the stage wearing a fox mask, enacting strange and wonderful scenes extracted from Under the Glacier, a 1968 novel by Icelandic author Halladór Laxness, spliced with Icelandic folklore. Moran crafted sonic architectures in the background that anticipated and dramatized her actions. Slides of glaciers melted while Jonas’s performance melded together didactic lessons on climate change and a hazy, half-formed narrative that felt akin to a creation myth: collective, spritely, full of life.

“As the worlds of art and activism increasingly meld together, performance seems like the de facto medium to address climate change”

In 2017, artist Lars Jan and Early Morning Opera installed a performance-installation, Holoscenes, in Times Square. Over the course of the three day-long performance, a human-sized twelve ton glass aquarium slowly filled with water as performers went about increasingly difficult mundane tasks like making the bed. Framed by an operatic score, the performance became something akin to a climate change ballet.

Joan Jonas, Reanimation (Installation view) 2010, 2012, 2014, 2018. Private collection © 2018. Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York : DACS, London. Photo © Tate (Seraphina Neville)

As the worlds of art and activism increasingly meld together, performance seems like the de facto medium to address climate change—as much for its urgency as its publicness, and its capacity to serve as an occupation strategy. All of which brings us back to The Great Animal Orchestra and softer modes of intervention. What is the end game of sitting in a black box listening to the ecstasy and erasure of non-human life? Does that anxious feeling of emptiness instil a will to act outside the gallery, and ought it to? “Blotting out visuals and relying on other senses to bring people into the here and now is a good start,” suggests Matt Clark, founder of UVA. “It’s also about inspiring collective action, because no single artist or scientist can fix this alone.”

Krause spent a lifetime trying to show that the health of an ecosystem is best understood by how it sounds, not how it looks. Our current position in the anthropocene could be understood as a problem of images, of tuning out the multi-sensory clues coming from the world around us. It was, until very recently, a position of “business as usual” because all looked fine from our own vantage point. Now, it’s time to close our eyes and listen closely to what other species are saying.