The first image that I woke up to one morning on Instagram depicted a solo tin of brined anchovies, half-open, the metal lid curled like a knife against butter. The image was labelled “From the back of the cupboard” and was framed singularly on a mid-century modern kitchen table, sleek and alone in its sparse, tasteful environment. Someone I follow on Instagram recently posted an image from lockdown; having left London to stay in their partner’s large family home in the countryside, they wrote that they were using the opportunity in quarantine to “reconnect with the land”; that they were learning to restore vintage fabrics; to scavenge for Lungwort; to dye balls of linen; to make salted dandelion flower fritters from the garden. At the same time, my Instagram feed abounds in photographs of people brandy-ing and jarring peaches in Kilner jars, growing sourdough starters, and just popping to the grocery store to replenish “provisions”.

All of a sudden, in lockdown, everyone around me seemed to embody an almost governmentally-mandated resurgence of the Blitz Spirit. An aestheticised version of austerity, of lack, of #BackToBasics, seemed to be ubiquitous across social media. Paradoxically, for all its inclinations towards thrift and scarcity, this is fundamentally a bourgeois, middle-class aesthetic; a perversely aspirational visual code that attaches moral value to rationed, scarce and portioned out lives. While by no means a universal for all working-class people, if I think about walking into my mother’s home, or those of anyone in my family, there is very different visual language, virtuosically opposite to that of Kilner jars and images of a singular, lonely boiled egg.

“Paradoxically, for all its inclinations towards thrift and scarcity, this is fundamentally a bourgeois, middle-class aesthetic”

So why are our timelines abundant with images fetishising lack and frugality, photographs that use scarcity—one peach in a bowl grown from the allotment—as the logical aesthetic principle? How does the invocation of Blitz Spirit and nostalgia during Coronavirus force us to become the ideal, self-possessed individual in keeping with neoliberalism’s desire for self-organising, calculating, entrepreneurial subjects, who are wholly responsible for their own life outcomes? What is this cultural trend, an aesthetic of lack and shortage, that abounds on social media? And how are they entangled, as Stuart Hall might argue, in British austerity culture and its relationship to neoliberal governance?

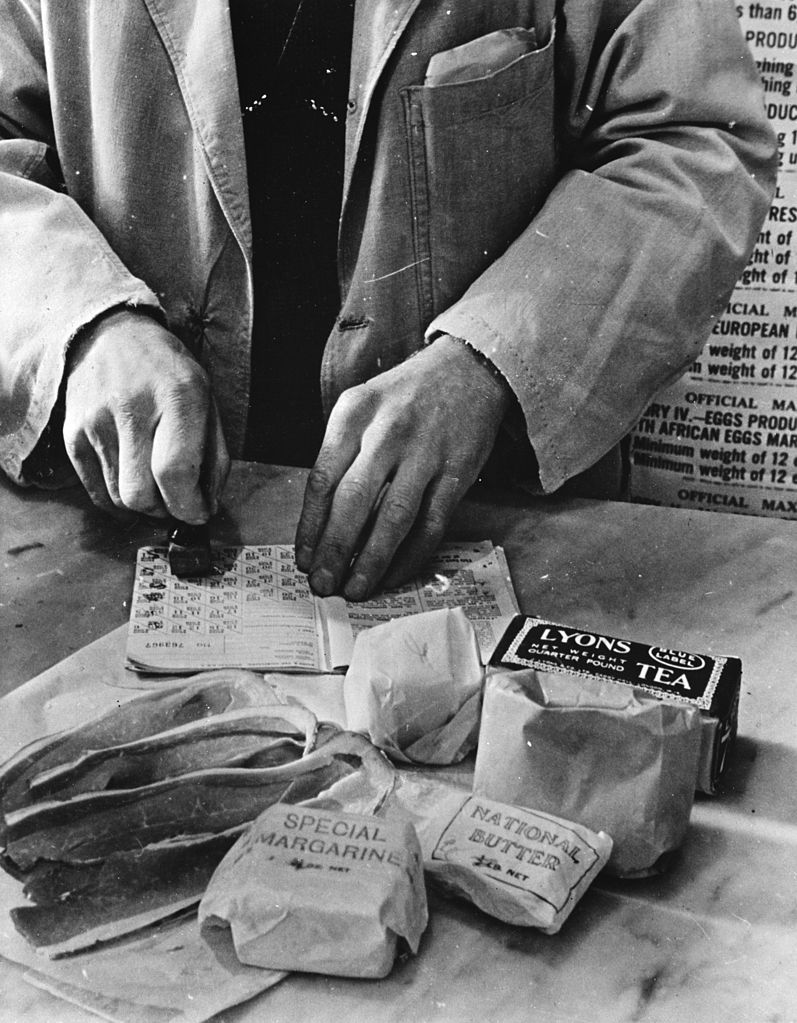

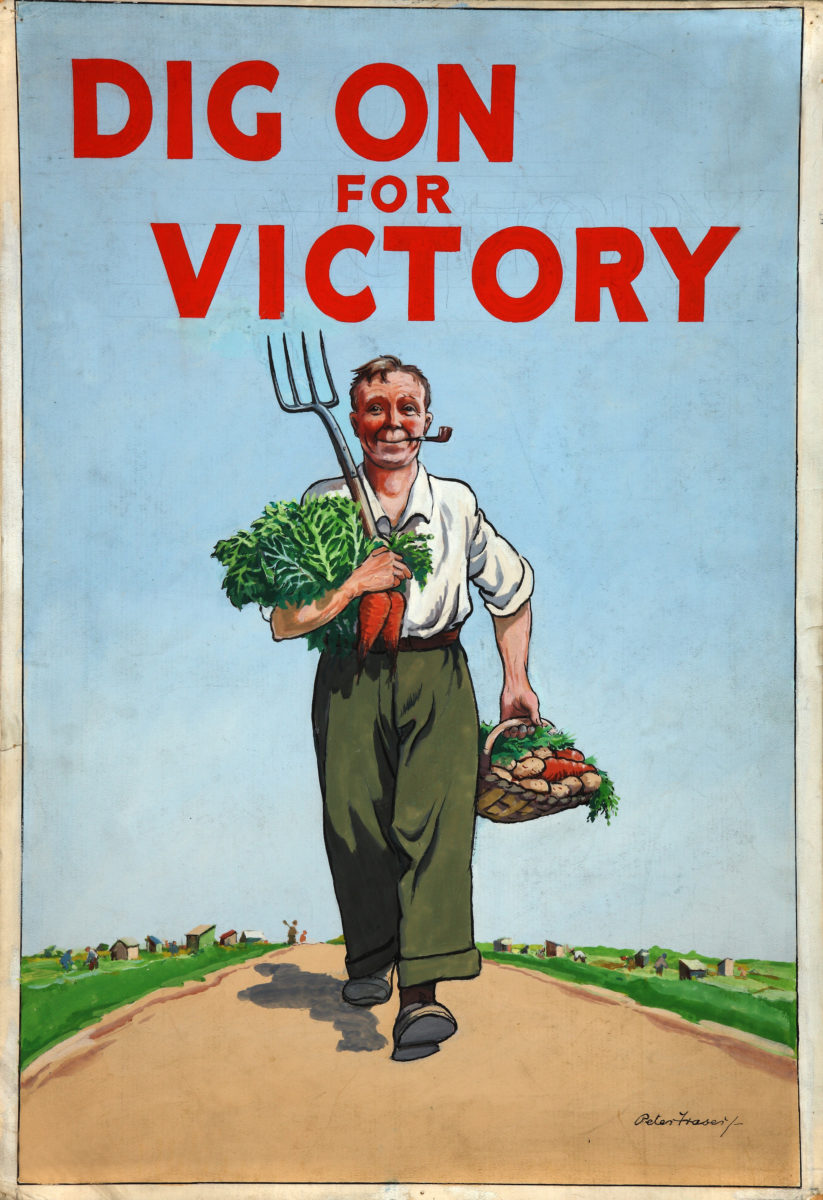

During and after the second world war, Britain faced an unparalleled period of austerity. As finances were directed towards other ends, government campaigns had encouraged citizens to “Dig for Victory” and to “Make Do and Mend”. Worn clothing to be repaired, broken furniture to be mended, and a reliance on the land had become quotidian staples of the war’s public mentality. Of course, when the war was over, people weren’t expecting that this austerity would continue, let alone worsen.

Austerity in Britain over the last hundred years or so has coalesced at certain moments, from Thatcher’s Britain to the late millennium’s financial crash. From 2010 to 2020, Tory cuts have obliterated education, health care, employment and scaled back other welfare entitlements; as Gargi Bhattacharyya writes, there has been the creation of “systems to assess ongoing entitlement or disentitlement”, all in the name of austerity. Bhattacharyya argues that austerity relies upon ‘crisis-rhetoric’, and there has been no greater time than a global pandemic than for the government to spool out a public outlook that mandates the individualisation of resilience and self-care. It signals the rise of the do-it-yourself attitude—you are not entitled to any more than what you can quite literally create for yourself.

As someone I follow on social media posts an image of themselves darning their old linens or tastefully posing an image of kippers on toast or just nipping to the shops, they are essentially promoting themselves as resourceful and resilient subjects. Neferti X. M. Tadiar defines neoliberalism as that which “signifies the greater role that finance, or interest-bearing capital has come to take in the hegemonic social imaginations of the present.” During coronavirus, what is featured in these digital images lends itself to the discourses of self-empowerment that neoliberalism requires, and that austerity actively promotes.

Léonie’s Mum’s House. Photo by author

In her house, my mother takes pride in gaudy imitations of fancy, bourgeois interiors: a plastic globe that opens to reveal bottles of alcohol; a mirrored Marilyn Monroe clock; an ornate armchair painted silver, with a graphic black and white image of a union jack on the seat covering. While she would happily wax lyrical about Winston Churchill, her home proffers a palpable rejection of modern Conservative policy through her desire for abundance, glamour and prosperity. It is a refutation of Crisis Times Austerity, and of the idea that we can Keep Calm and Carry On against the pandemic with some handmade jute bags and carefully arranged copies of the

London Review of Books

. My mother’s house is what many would call gaudy and tacky, and she revels in it. Her interior decoration is a visually messy antidote to the austere middle-class asceticism and aestheticism that seems to abound on social media at present.

During coronavirus, there are ways in which this regression back to “a simpler time”, with its closer relationship to the food that we eat and the goods that we use, could constitute a radical rejection of our commodified culture and age of hyper-consumption. However, this aestheticisation of lack for lack’s sake is not that. Crucially, this new model of entrepreneurial spirit unfolds and formulates itself in the field of the visual, taking the form of images that elevate austere and clinical scarcity. Rather, this person, as they darn their clothes or actively scavenge in the garden, or “Carry on Gardening”, is the making of a bourgeois subject. They are that which is resourceful, has the land in order to rely on themselves, and that which is deep in their pantry to sustain them.

“This new model of entrepreneurial spirit unfolds itself in the field of the visual, taking the form of images that elevate austere and clinical scarcity”

This position, and the way it lends itself to smooth, clean visual forms, is predicated on the very idea of neoliberal self-fashioning that underpins the vicissitudes of contemporary capitalism. If you have the space you can grow your own seedlings and vegetables from germinating offcuts, and if you have the time you can painstakingly nurse your baby sourdough starter to strong, bubbly health—large gardens and swathes of personal time being two things that most normal, lower-middle or working-class people do not have. “Self-reliance” is aspirational, while messy social imbrication and communal need are disregarded, if not derided.

I return to the image of someone I work with who gives day-by-day Instagram-story updates on the progress of her germinating vegetable offcuts. She has salvaged the tops of onions and the ends of carrots, she has made cuttings from the scraps of rosemary and chard tied with rustic twine, and is painstakingly growing each one in its own meticulously cared-for bed. Every day she is dismayed at their continual tiny green deaths. The thing is, we are all a product of much closer and messier growing situations, and our roots must stretch far and wide if we are to survive. As John Donne might say, no man is a single leek entire of itself, no matter how carefully, resourcefully, and artfully cultivated in quarantine.