Few places in the United States sit more uneasily in the cultural imagination than the South. A region vital to the country’s cultural and political development, its identity is mired by centuries of violence and oppression. Meanwhile, in part due to this troubled history, few places in the US have been more mythologised.

In 1996, the High Museum of Art in Atlanta

, Georgia, began commissioning photographers from across the world for its Picturing the South initiative. The idea was that they would move beyond the clichés and stereotypes and create a new visual vernacular for the South, shedding light on narratives previously untold.

Together, the 16 artists commissioned so far have produced more than three hundred photographs documenting the South’s ever-evolving social and geographic landscape, exploring themes such as the legacy of slavery and racial justice, the impact of environmental change, and the diverse character of the region’s people. As High Museum curators Gregory Harris and Maria L Kelly note: “In many ways, to understand America, one needs to grapple with the South.”

To mark the programmes 25th anniversary, the High Museum is staging Picturing the South: 25 Years, a major exhibition that brings together all the commissions for the first time. Here are some of the highlights.

Alex Webb, Atlanta, 1996

Among the first artists to receive a commission, Webb set out in 1996 to capture the energy and drama of downtown Atlanta, a city on the up as the booming capital of the “New South”. Wandering the streets with a small handheld camera and an improvisational approach, Webb pictured the mingling of crowds, cultures and forms. Daubed in an inky purple light, Atlanta’s high-rises are contained twice within this densely-layered image, which evokes the electric intensity of the city.

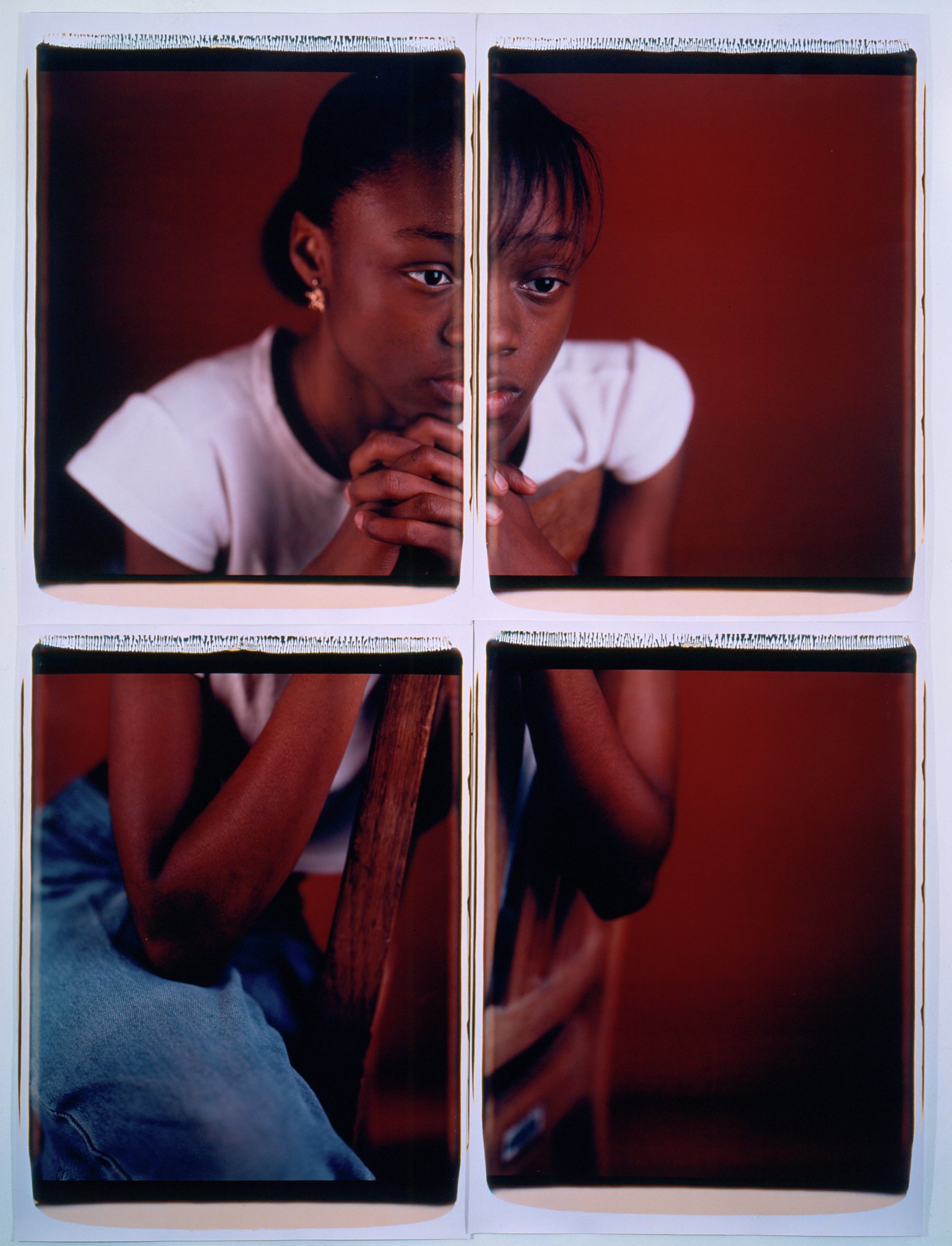

Dawoud Bey, Kanisha, 1996

Renowned for his complex and compassionate portraits of Black subjects, Bey set up his camera inside Tri-Cities High School in Atlanta for his commission. He collaborated with the students to produce a series of multi-panel portraits, drawing on the poses of Dutch master Rembrandt in an effort to “challenge prevailing notions about African-American teenagers, a group that is seen by the dominant culture as almost uniformly one-dimensional” and create a “sense of heightened, commanding presence for those who have traditionally been ignored or maligned.”

Emmet Gowin, Aeration Pond, Toxic Water Treatment Facility, Georgetown, South Carolina, 2001

For his commission in 2001, Gowin continued his decade-spanning exploration of the Anthropocene by photographing paper mills across the South. Rather than picturing the factories themselves, he took aerial shots of the damage done to the surrounding landscape. In his eerily beautiful images, toxic chemicals swirl and bloom across ponds and streams. “Everything which human beings do, every activity, leaves its mark,” says Gowin, reflecting on his distinctive depictions of human interventions in the natural world.

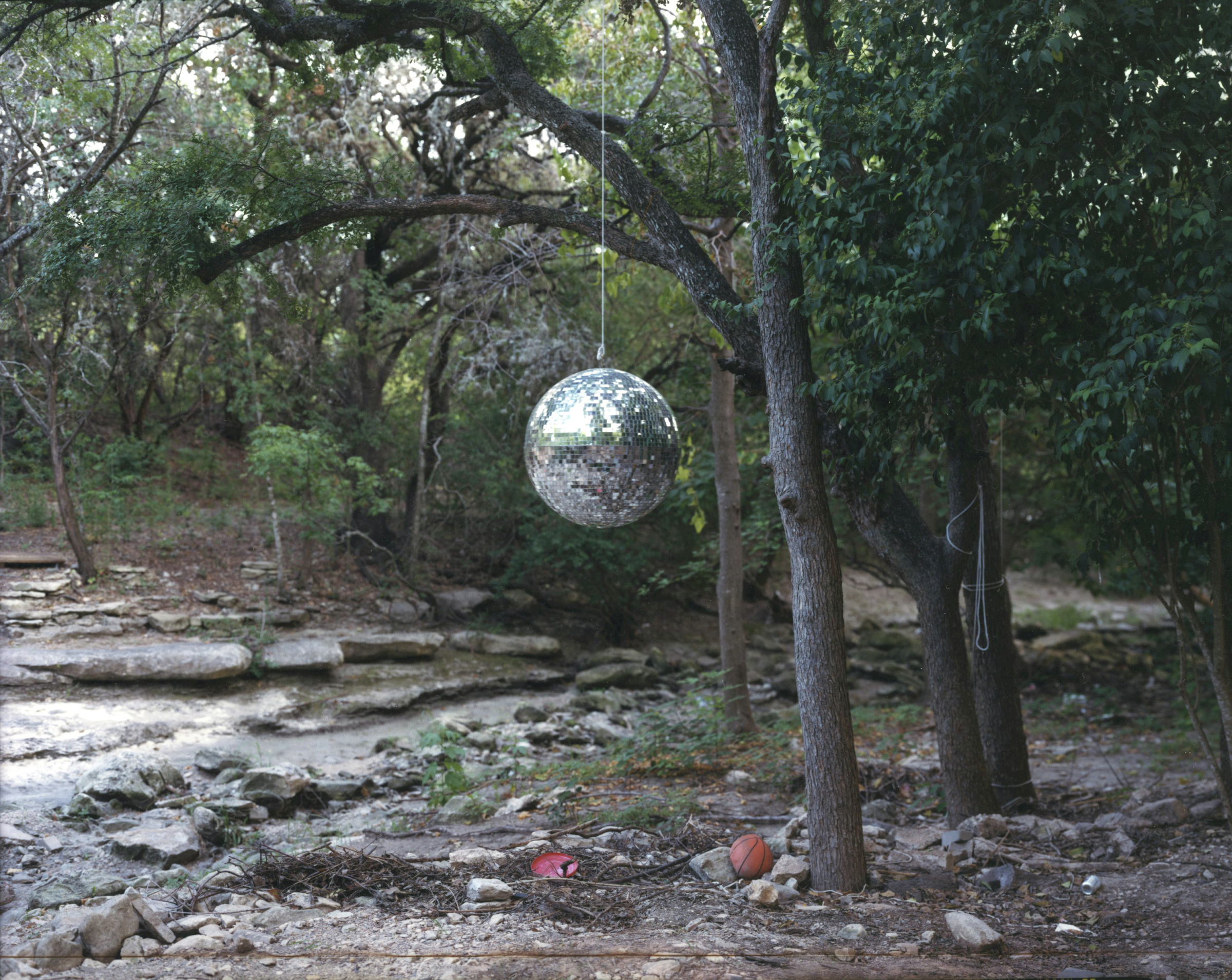

Alec Soth, Enchanted Forest, Texas, 2006

The incongruity of a shiny disco ball dangling in a wood, extracted from its home on the dance floor, reaches to the heart of Soth’s project, which probes the romantic notion of escape. In 2006, he ventured into the countryside of Georgia and North Carolina to photograph those who choose to live outside organised society, from monks to hermits. His images demonstrate a respect for solitude as well as an awareness of the more sinister reasons behind a withdrawal from civilisation.

Kael Alford, Joseph and Jasmon Jackson Play in the Bayou, Isle de Jean Charles, Louisiana, 2010

After years spent photographing war zones, Alford adopted a slower pace for her commission. She documented the precariousness of life in two native enclaves in Terrebonne Parish, Louisiana, threatened by coastal erosion. Drawn to these communities because of their deep ties to the land, and her own Native American lineage, Alford captured a narrative that “unravels at a geological pace”, creating poignant portraits of individuals who continue to live on ancestral ground despite the devastating effects of climate change.

An-My Lê, High School Students after Black Lives Matter Protest, Lafayette Park, Washington, D.C., 2020

Since the 1990s, Vietnamese-American photographer An-My Lê has explored the impact of violent conflict on the American psyche. Her contribution zooms out of the South and lenses the legacy of its fraught history in Washington, DC, focussing on the social unrest that emerged after the murder of George Floyd in 2020. This image portrays a group of friends hanging out after a Black Lives Matter protest, at once a gentle summer scene and a telling depiction of how past divisions and traumas still shape the present.

Sheila Pree Bright, Stone Mountain, from the Invisible Empire series, 2019-21

A long-time chronicler of the culture and lived experience of Black Americans, Bright was invited to expand upon her 2019 photo essay about Stone Mountain, a solitary granite mass of rock just outside Atlanta that was once a meeting place for the Klu Klux Klan and is home to the world’s largest confederate memorial. Bright addressed its history obliquely, producing stirring black-and-white photographs of the surrounding landscape that quietly contemplate the discord between Georgia’s natural beauty and the horrific events that took place on its land.

Abelardo Morell, Camera Obscura: View of Atlanta Looking South Down Peachtree Street in Hotel Room, 2013

Morell’s depictions of Atlanta reach towards magical realism. Best known for his use of the room-sized camera obscura, an optical technique which projects exterior views onto interior spaces, the photographer overlaid images of the city’s leafy skyline onto hotel rooms and domestic settings, merging the metropolis with private inner worlds. “One of the satisfactions I get from making this imagery comes from my seeing the weird and yet natural marriage of the inside and outside,” he explains.

Alex Harris, Abducted, Waxhaw, North Carolina, 2018

A native Southerner, Harris

’s project is preoccupied with the stories told in and about the South. In 2016, he began photographing more than 40 independent film productions from Louisiana to Virginia, considering how the South is portrayed. Blurring fiction and reality, he captured staged scenes as well as moments on set and in the surrounding communities. In documenting the concerns of independent filmmakers, from racial tensions to friendship and solidarity, his series holds up a mirror to society at large.

Mark Steinmetz, Untitled, 2016

Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport, America’s most heavily trafficked airport, is the main character in Steinmetz’s series. The photographer spent two years documenting the everyday dramas, emotions and experiences that played out there. In this strangely serene image, a passenger rests on a baggage trolley, warming their legs in the sun as the smooth lines of the terminal building opposite curve away. “I want to photograph the depth of people, their inner life,” Steinmetz explains. “I like the idea of a quiet interlude in a crowded place.”

is a Berlin-based journalist specialising in culture and current affairs