The first place I visited in Hong Kong during this year’s Art Week was not a gallery or a museum, but an old house in Sha Tin in the New Territories. A VIP tour for Art Basel HK organized by Galerie Ora-Ora brought a group of people there by minibus. First, the high rise buildings of the newly developed town appeared, but on the other side of the river we stopped by an old rural house built in the 1800s—the sole remnant of the historical Wong Uk Village, which had served as a trading station for merchants to move goods between Guangdong and Hong Kong.

Tropical rain was pouring down on that Sunday, but Lam Tung-pang, the artist who was showing us around, said that we were lucky to come on a rainy day. I wondered why, but for a moment Lam left that open. He had filled the empty house mainly with sculptures created out of 20th-century furniture—low-rise cabinets and sideboards made of wood and bamboo—and bonsai-like potted plants, elements through which he was creating a dialogue with the house.

When entering the courtyard in the middle of the Old House the connection to the rain suddenly became obvious. Here it was pouring down heavily, but the artist had placed a dollhouse with plants growing out of its roof and windows in this outdoor space. The miniature model was inspired by Lam’s ancestral home in Fujian, China, which also has an open patio designed to sustain bad weather as it helps drain water in heavy rain.

The next day this peaceful, slightly nostalgic and touristy adventure was contrasted by a show called .com/.cn, which looked at the intersections between post-internet practices in China and the West. When I arrived at K11, Miao Ying was the centre of attention. She was sitting inside her artwork on a reclining chair surrounded by tablets in various sizes mounted to her chair. On the screens in front of her eyes landscape compositions of flickering gif images were distracting from her relaxed body position. On the floor sheets of crumpled paper with the Chinese character “zan” which is equivalent for “like” on Facebook littered the ground. With this “garbage of likes” Miao Ying criticizes social media platforms for not typically having a dislike bottom: “If you like everything it becomes meaningless.”

At Art Basel HK Miao presented one of her Effect (2017) paintings at Galerie nächst St. Stephan Rosemarie Schwarzwälder. I must admit, that when I first came by the booth I didn’t recognize it as her artwork. I had expected something digital. The painting showed digital effects outside their use. By looking at them without context and through the shift from the digital signal to the analogue painting, Miao was deconstructing the effects we can so easily use nowadays.

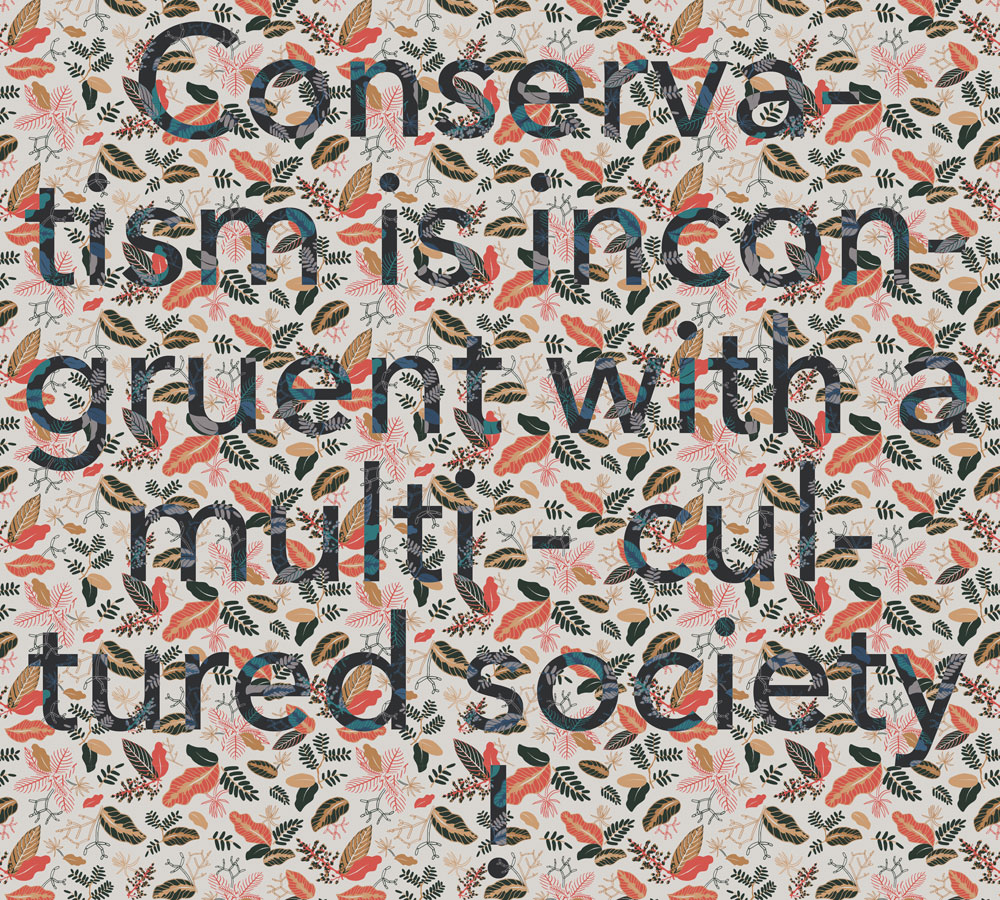

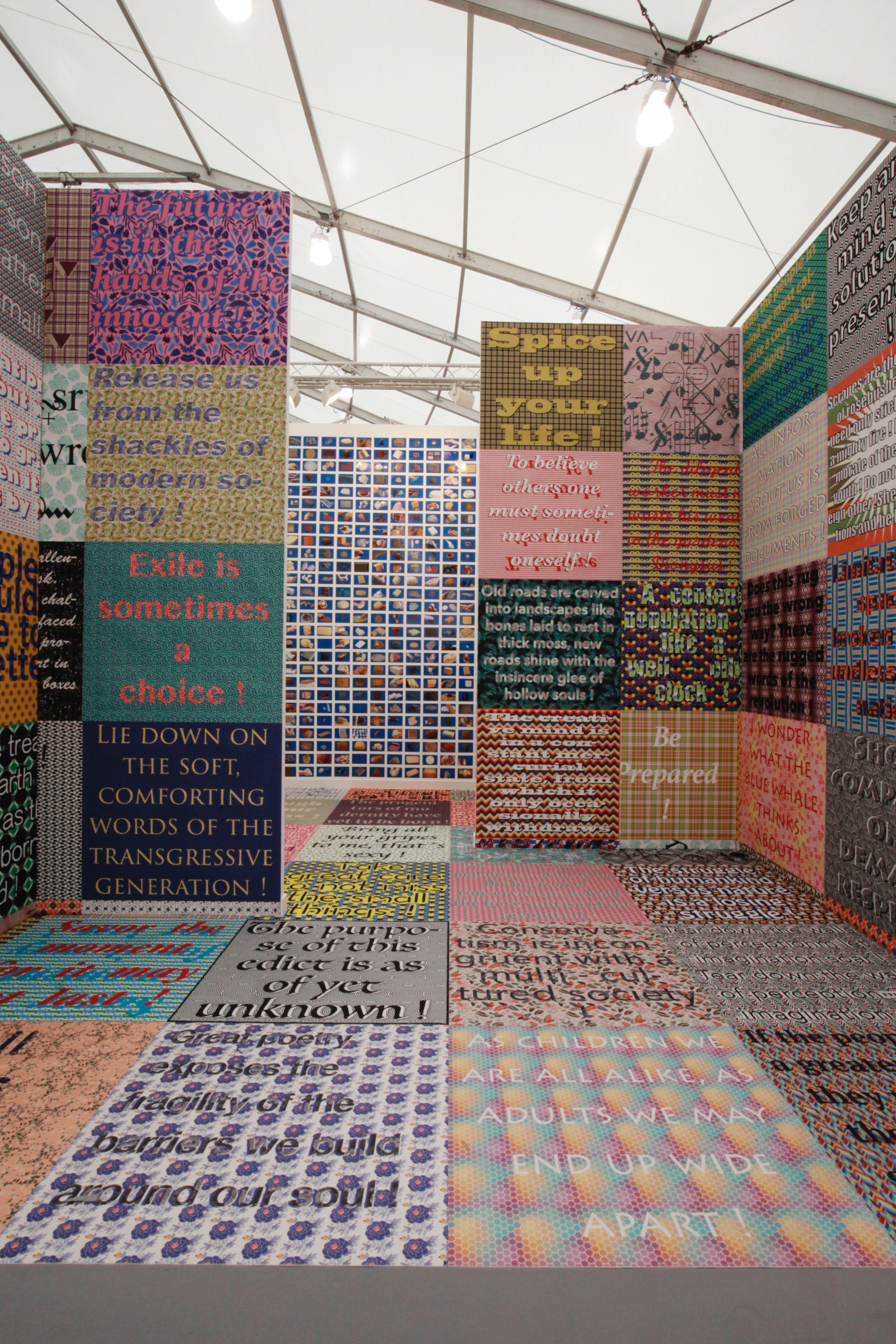

Another popular work during the opening at K11 was from Liu Shiyuan. Tiles of coloured carpets with slogans written on them took over walls, floor and ceiling in one corner. I found the work too obtrusive and had little desire to engage with it. When I almost accidentally got closer to it, a girl who stood next to me said with admiration: “It is very smartly installed, so many people, but you can’t go inside.” She made it sound as if it was resisting the masses, but only a few minutes later the situation was completely different. An assumingly very important man positioned himself right in the middle of the installation to have his picture taken.

Purely by coincidence the first show I went to, after K11—Tatiana Trouvé at Perrotin—involved carpets as well. Various beige rugs covered the entire gallery floor so you were forced to walk on them, but often they weren’t entirely rolled out. People kept stumbling over the carpet rolls and at the same time some of the ephemeral sculptural set-ups looked as if they could collapse at any time.

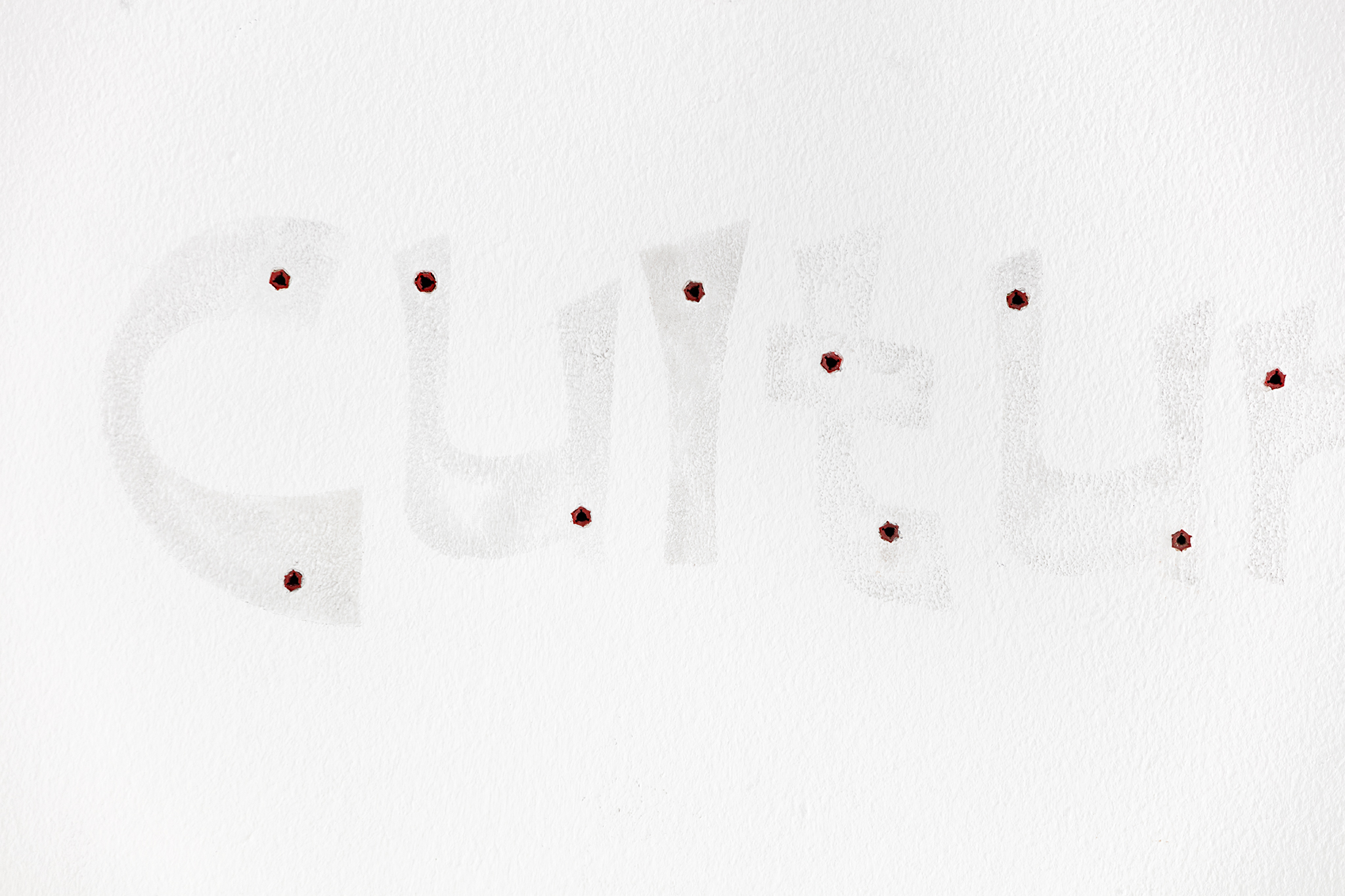

On the first preview day at Art Basel there were already so many people that I found it hard to engage with the artworks. Kukje Gallery’s installation for the Kabinett section, where galleries presented a curated project, was the first artwork that captured my attention. It was an archival exhibition about Kwon Young-Woo, who used hanji (Korean paper) as his primary material. One of the unique features of his works from the 70s are holes. The artist used his fingernails and other tools to cut, tear and puncture the paper. I have read about Dansaekhwa artists before, but to stand in front of a real oeuvre makes a huge difference, finally I could experience its materiality.

Another discovery from the Insights section was an exceptional historical solo presentation by Kazuyo Kinoshita at Gallery Yamaki Fine Art. I particularly like her conceptual photographs from the 70s. By juxtaposing two and three dimensions with very simple means—black and white photography and outlines of geometrical shapes with a coloured felt-pen—she creates an irresolvable tension between both perspectives.

The third booth I was pleased to come across was from gb agency. A piece that nobody needs (2012) by Pratchaya Phinthong offered a much-needed breathing space from the spectacle of the fair. The artist had framed a white piece of paper that was previously taped on the wall in two of his exhibitions. In another piece Phinthong showed a black ball created from Yttrium—a rare earth mineral, of which China owns more than 90% of the world market. A photograph taken by a global satellite run by Japan and the USA accompanied the sculpture. It is an image of the largest rare earth mine in Chinese Mongolia. Besides the geopolitical issues, the piece drifts towards a sensual aesthetic that examines processes of transformation. In a similar way, it felt like the artworks by Ryan Gander that I came across at Esther Schipper’s booth and at gb Agency were witty takes on art that were very much needed at a fair where it seems to be a disaster when you haven’t sold out on the first day of the preview.

Liu Shiyuan. Installation view, Liu Shiyuan, This Way or That Way, 2016. Courtesy of the Artist and LEO XU PROJECTS, Shanghai.