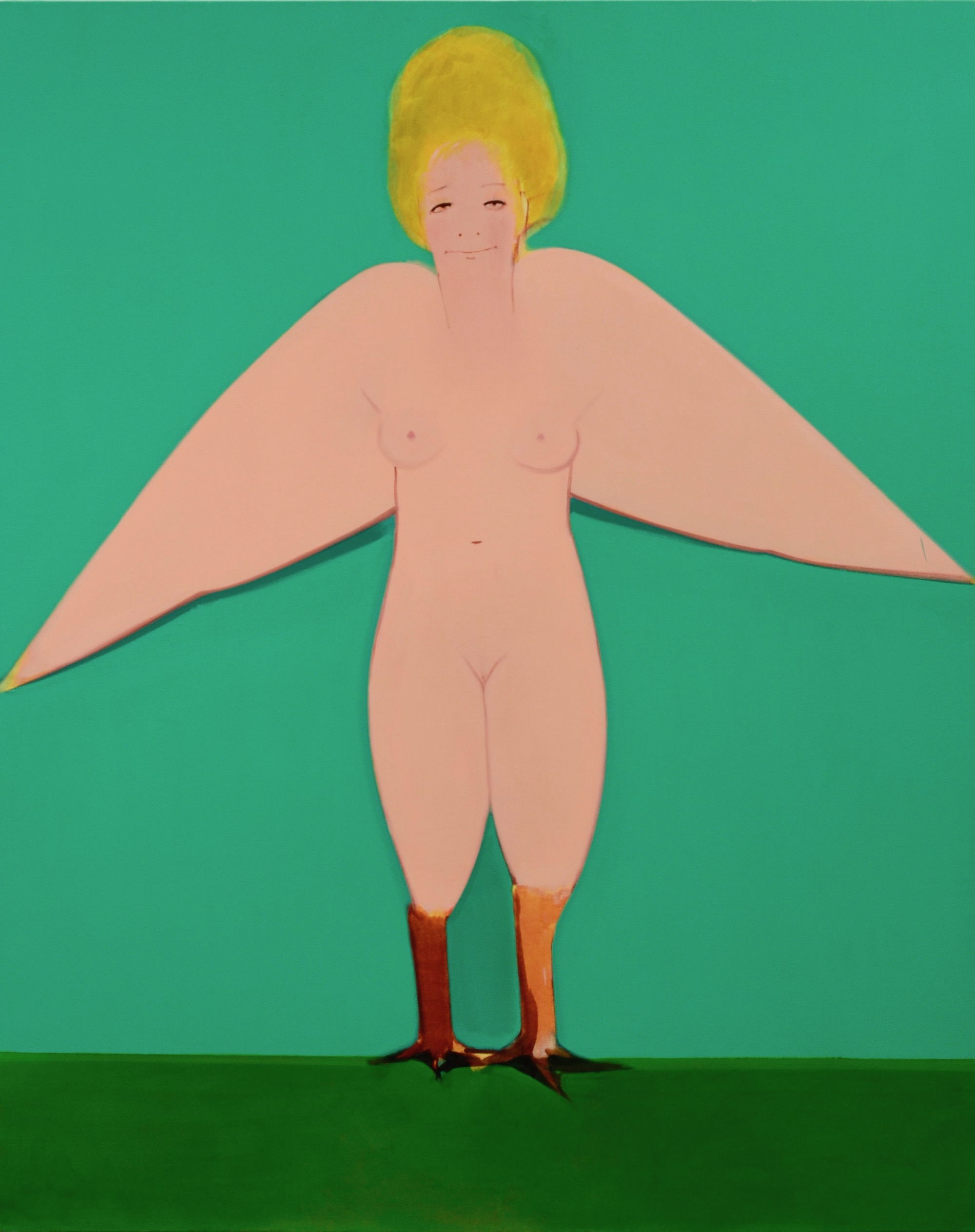

In the paintings of Sofia Mitsola, the women in the frame aren’t just there to be gazed at; look at them, and they’ll look straight back. Mitsola’s women are defiantly seductive, unafraid of their own sexuality and in control. The female form morphs and transforms across the canvas, playfully alluding to mythological tales of sphinxes and sirens and their wise, wily ways—as detailed most famously in Homer’s Odyssey. It is little surprise that Mitsola nods to the fantastical tales of Ancient Greece, hailing as she does from Thessaloniki, where the many layers of the city’s past are never far out of sight.

Now based in London, Mitsola completed an MFA in Painting at Slade School of Fine Art last year. Visits to the ancient Egyptian and Greek sculptures at the British Museum have influenced her paintings of youthful goddesses of yore, while a minimalist style and preference for bright, block colours bring a striking, inquisitive atmosphere to the works that feels firmly rooted in the present.

You often reference mythical creatures and Ancient Greek and Egyptian sculptures. What led to your interest in these characters, and how do you view them in the context of our contemporary reality?

A couple of years ago, my work was not figurative. I was painting landscapes with architectural elements, which allowed me to explore geometry, composition and colour. This was a kind of exercise to learn more about ways of painting and what I was interested in. But I always wanted to bring figures into the paintings, and it was hard because I did not know where to start from. However, the decision to do so came naturally as for quite a long time I was drawing figures, even though these did not make it into the paintings. I was also sketching a lot from sculptures or paintings whenever I visited museums. So when I started to work with figures, questions came with them: “What will they look like?” “What is their size and scale?” “Who will they be?” “What is their relationship with the viewer?”

I began my research by looking at ancient Egyptian and Greek sculptures at the British Museum. I was attracted by their geometry, their tall, lean, strong figures and what they represented: young eternal goddesses of the past. I became very interested in mythical creatures like sphinxes, which have a different meaning across cultures. In ancient Egypt they were goddesses and protectors, whereas in ancient Greece they were monsters that would strangle men and devour them. I really liked this dual meaning of the same creature interpreted by two cultures, and I started to think of how I could use this in my characters, and how this idea would form the figures that I was trying to compose.

“I am interested in the act of looking and being looked at, and the pleasure and the discomfort that this might cause”

- Left: Toy Sphynx, 2019. Commissioned for Jerwood Solo Presentations 2019. Photo by Anna Arca. Right: Sphynx, 2018

The female figure is the dominant theme of your paintings. Who are the women that you depict, and how do you relate to them as a female artist?

In my mind, my characters are like sphinxes and sirens, seductive creatures that use their sexuality as their power to get to their actual purpose, which is to strangle and devour. With their gaze, they are inviting the viewer to look at them, and at the same time they are in power; they are in control. The viewers accept this invitation as they look back, and in a way they put themselves at risk.

I am interested in the act of looking and being looked at, the pleasure and the discomfort that this might cause and the relationship that this creates between the painting and the viewer. When I am painting, I feel that I am playing a role—I need to become them—in order to make them exist. At the same time, I have to detach myself from them, to step back, and become the the viewer if I am to see what they do as an image, and what impact they might have. It feels like a constant state of trying to get in and then get out; to look from within and from a distance.

How has your relationship to female sexuality shifted while you have been working on this subject, and how do you choose what to hide and what to reveal with regards to nudity in your work?

Working with a completely new subject, I came to realize (in a more concrete way) what I wanted to do with painting, and how to find ways of pushing it. I feel that working with the female form, I am able to play with ideas of confrontation, power, control, pleasure and repulsion, in a much more direct way, which I could not so easily approach otherwise. At the same time, the change from non-figurative painting to figurative has happened very organically, and has come from the excitement working with the female nude, which is a subject that has always fascinated me. This shift has opened up my practice, and more questions keep coming up which eventually will give way to new work.

When it comes to choosing what to hide and what to reveal, for me this is always driven by what the composition needs and where I would like to draw attention towards. When I am painting, I am thinking of what will happen when an element or colour is added to the work and how this changes the balance of the image and the composition. I add and hide elements as I build up the painting and so the work that might start in a certain way could end up completely different. In the same way, I work with the clothing that my figures might be wearing. A sheer top can become a device to break up the flatness in the tone of the flesh, but also to highlight the nudity which is revealed through being covered.

You are originally from Thessaloniki in Greece. How has your background influenced the work that you make, and how has that shifted since moving to London?

Thessaloniki is a very historic place, and its past is layered across the city. If one walks down the streets, they can see the architecture of the contemporary city and, just a few metres below the ground, the Roman city and the Byzantine city. These seem to co-exist and they all make Thessaloniki what it is; the old world seems very much part of the everyday life, too. Coming to London, I realized for the first time these special characteristics of my city, and I started to miss the old. I think this is one of the reasons that led me to spend quite a lot of time in the British Museum looking at the artefacts, which in turn have opened up new territory for me, and items or themes of the past started to appear in my paintings.

“I love painting. I love its flatness, its directness, its history”

- Left: Candyfloss Snowman, 2017. Right: Mount, 2016

At a time of hyper-connectivity in the digital age, what have been the pleasures and challenges of the process of painting and drawing, which are both so rooted in a traditional (and historically male-dominated) craft?

For me, painting and drawing are such exciting mediums to work with. I find drawing essential as it helps me to plan the paintings, loosen up my lines and get a sense of the “atmosphere”. I find that it is a very enjoyable and quick process, with which I can experiment by using different materials, sizes and “rhythms”. Painting feels like the medium that I am most attracted to and is the core of my ideas; everything seems to evolve around it. I love painting. I love its flatness, its directness, its history.

For me, as a young painter it is such a luxury to being able to visit museums like the National Gallery in London and see how the history of painting has developed through time and different contexts. With painting, I feel there is a great source of material with endless possibilities that can be studied and explored with a contemporary view. It seems that now is a great time to see how different subjects will appear, bearing in mind the fact that artists from all backgrounds have more opportunities to show their work. I think of how these works will add up to the history of painting, and what will survive in the test of time.

Chariot, 2019. Commissioned for Jerwood Solo Presentations 2019. Photo by Anna Arca