Meka Boyle explores the labour of love and ways of consuming behind a queer cooking collective ran by Precious Okoyomon, Quori Theodor and Bobbi Salvör Menuez.

Food is poetry for Precious Okoyomon, Quori Theodor and Bobbi Salvör Menuez, the trio behind the queer cooking collective Spiral Theory Test Kitchen. Within every messy, fermented, gooey, piquant home-spun meal served up by STTK, there is a nuanced dissemination of ideas around identity, creativity and community. True to the spirit of subversion, new ways of seeing the world sprout up in between spoonfuls of floral aspic and flavourful bursts of fermented oddities.

“Our work overlaps and weaves through our queer identities, our trans identities, both individually and as a collective”, says Salvör Menuez. They have set out to dissolve the hierarchy of higher dining, they each emphasise, making room for new ideas around what it means to cook and share food. “It’s such a restorative project. It developed organically from us being friends and saying ‘Let’s just cook together.’ It comes out of a place of joy and love”, says Okoyomon.

STTK was born in 2018 in the kitchen of Salvör Menuez and Theodor over shared homemade meals like a comforting yam porridge based on Okoyomon’s mother’s recipe that the artist recalls fondly. “I remember we had a lot of kale flowers that we put in”, they recall. “We each changed the recipe in our own way with the little things we all brought into it that made it ours. There’s something really lovely about that.”

Since the collective’s early days—when an overwhelming interest prompted the three to set up an automated response email that read “We are not synced up to linear time. Do not wait on an answer from us”—STTK has been reborn countless times. And in the years since its inception, a new wave of experimental artist-chefs have joined its cohort. “When Spiral Theory started, there weren’t many people around us doing this practice”, Theodor says. “Now I see more people coming up who are doing it, or who are using different biomaterials in terms of sculpture that are leaking into these areas. It’s cool to see. Bring it on”, says Theodor, citing conceptual artists like Gordon Matta-Clark and Rirkrit Tiravanija as the STTK’s closest predecessors.

The project, a labour of love, ebbs and flows between each member’s individual creative projects, of which there are many—from Salvör Menuez’s leading roles in various films and performances, to Okoyomon’s art exhibitions and poetry, to Theodor’s year-long multi-sensory culinary-art installation at Performance Space in New York.

Their shared project offers the ambitious artists a pressure-free place to recharge, check in, foster creativity and have fun away from the mythos of the solo genius. “There’s such a desire or ease of marketing an individual, like the art star, the famous chef”, says Salvör Menuez. “Everyone’s an influencer now. That culture can be so alienating and so disconnected. It’s so meaningful to have a space where we’re acknowledging the cross-pollinating nature of creative practice; it’s hard to actually parse out who came up with what and it really disrupts the understanding of a kitchen hierarchy or who’s the artist and who’s the great mind behind all these fun, weird ideas.”

Their month-long residency this summer at Unclebrother, an art gallery and restaurant opened by art dealer and artist Gavin Brown and Tiravanija in Hancock, NY, offered the trio fertile ground to experiment and unwind from the hustle and bustle of their busy city lives. “The food generated from that time was really lighthearted and really playful, in the spirit of what our collaboration is”, says Theodor.

Cooking is a secret lover’s language for STKK, full of inside jokes and made-up words. In Hancock, ideas materialised from the ambient creative time the group spent together—wading into the river, playing in a kiddy pool full of slime for Theodor’s birthday, and cooking together: simple eggs for breakfast and bountiful bowls of bean salad, sauteed greens and sweet potatoes served family-style on the riverbank. Every morning they trailed behind the turquoise shingle house where they were staying to jump in the river that snakes through Hancock.

The small, picturesque town that Unclebrother has called home since 2016 is about three and a half hours away from New York City, add an extra hour if you decide to take the train. Hancock is not in the Hudson Valley, and it’s not quite the Catskills; rather, it is at the tip of the Upper Delaware River Valley. There is a main street lined with white Victorian houses, a few thrift stores, a coffee shop and a scattering of restaurants. (Of course, if you venture further down the strip, you’ll run into the omnipresent capitalist trappings that are inescapable even far out in this rustic hamlet: the golden arches of McDonald’s remind us that we are in America, after all.)

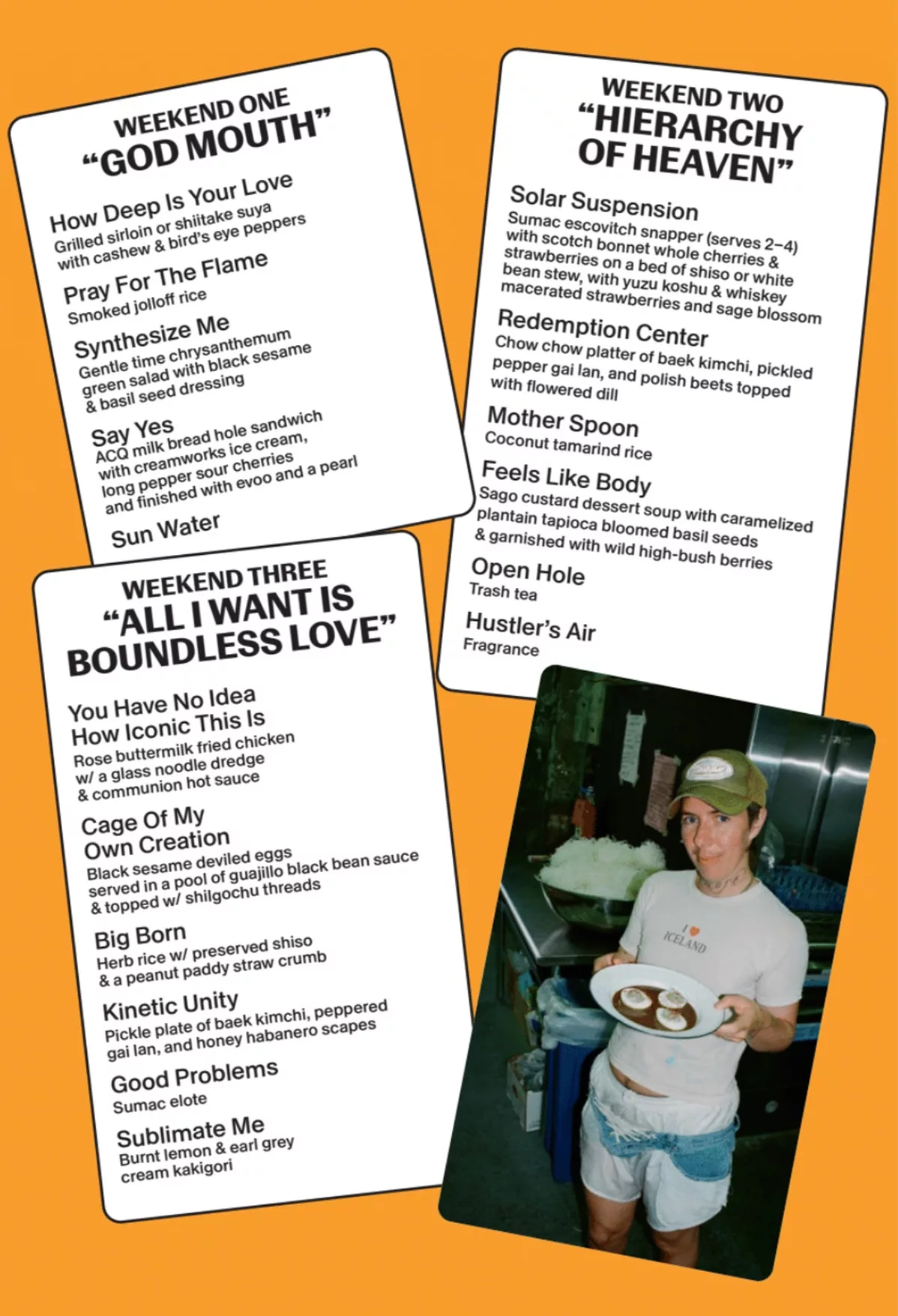

On any given day, a multigenerational assortment of regulars and newcomers alike can be spotted ambling past the idyllic storefronts, facades clad in American flags left over from the Fourth of July, and the occasional Make America Great Again sign, to fill the picnic tables outside Unclebrother and convene inside the spacious, sunlit dining room that used to be an auto repair shop. (This summer, the restaurant hosted a series of pop-ups featuring guest chefs blurring the line between art and food—a practice pioneered in the kitchen by Tiravanija himself.) For three weeks in July, Theodor, Salvör Menuez and Okokymon transformed the kitchen into a more accessible iteration of their perverse, post-supper-club, conceptual dinners.

“I learned a lot about people up there”, Okoyomon reflects. “We had our own sort of bubble, but the community did engage. For a while, our dishwasher was somebody who worked at the Trump flag station before he decided he wanted to do something different. We ended up talking with him and became friends. He felt really safe and accepted with us”, they say, noting that Unclebrother’s presence has created a palpable shift towards open-mindedness in the town.

“Unclebrother is changing how things work in Hancock. People are accepted by the community: People do change. God is change”, they observe. “I feel really blessed that we got to be a part of that”, they add, “interweaving, pollinating inside of those weird things bubbling up there—that is its own magic.”

On a late, balmy afternoon at Unclebrother, I found myself inspecting the space’s art gallery, where a provocative summer group show featured art-world heavy hitters and rising stars who included Jessi Reaves, Arthur Jafa, Louise Lawler, Uman, and Leidy Churchman. I lingered on a large colourful painting of an antelope by the prolific artist Uman, who lives and works elsewhere upstate. I exited the maze-like layout and followed the trail behind the gallery down to the riverbed. I paused to dip my fingers into the cool, trickling current, joined by the artist and digital stylist extraordinaire Kellian Delice, and Christian DeFonte, a photographer and friend of the trio who came along with me to document the trip. We killed time in the thrift stores around town until it was time to gather at the kitchen for meal prep.

Later in the night, after the restaurant was closed and the kitchen cleaned, we beelined to the river, joined by Travis Fairclough, Unclebrother’s resident artist and curator who works with Brown and Tiranvanija on the gallery’s operations and programming (and uses the turquoise house as his art studio during the off-seasons). We all stripped down and waded across the slimy pebbles to submerge ourselves in the cool water. There is the possibility of eels, Okoyomon offered, playing with the turn of phrase until it reached an ephemeral poem that dissipated into the dark, star-lit Hancock sky.

Earlier in the night, before the restaurant opened, Okoyomon, Theodor and Salvör Menuez materialised in the kitchen to prepare the final weekend’s menu. The three moved in unison; the chaos and toxic masculinity often associated with back-of-house culture was nowhere to be seen.

Four eager students, part of a summer-long residency, assumed their stations, chopping herbs and measuring sauces. The elder dishwasher tidied his station, while Roland Chen (the chef who would take over the kitchen the following week) tested his kimchi scapes. Outside the kitchen, Salvör Menuez and Theodor’s tiny white chihuahua SweePea timidly poked out of her carrier to inspect the scene out front before retreating back inside.

Produce from local farms including Gentle Time Farms, a trans-led co-op, was sorted for later use. The ingredients for black sesame deviled eggs, sumac elote, a raspberry compote-like hot sauce, and rose buttermilk fried chicken alchemised between the chef’s steady movements, perforated by laughter and gentle caresses. A massive bowl of dried glass noodles on the counter caught the afternoon sunlight.

The air was tinged with the scent of dill and large bouquets of mustard flower, borage, wild bergamot, sage, nasturtium and fennel that were propped up in buckets. Before the wildflowers made their way into the kitchen, they were stored in Okoyomon’s room, which, with the air conditioner cranked up, became a DIY walk-in refrigerator in lieu of a real one. The cool, fragrant room with foliage towering over a small bed could have been one of the artist’s own installations. “Poetry literally seeps into my everyday life: my life is unendingly filled with flowers everywhere”, Okokymon agrees.

As the kitchen opened, Salvör Menuez arranged the edible petals and spindly stems on plates of rose fried chicken, which Okoyomon had prepared with a mix of aromatic spices, some passed down from their mother, who previously owned a restaurant when their family lived in Lagos. “If you can really handle the spice, you get to the magical floral quality of it”, says Okokymon of their medley of dragon fruit, raspberry and rose powder blended with green szechuan, pink peppercorns, ghost pepper and smoked scotch bonnet.

The first wave of customers trickled in at 8.00pm. They propped up their elbows between deliberately haphazard displays of corn husks, egg shells, fennel and mustard flowers, waiting for their order numbers to be called.

‘Cage of My Own Creation’ arrived first at our table: the devilled eggs were surrounded by a pool of blackbean sauce and garnished with shredded red pepper. DeFonte and I shared each dish so we could try everything on the menu. We scraped our spoons in the shallow bowl and relished the faint spicy kick that lingered in the back of our throats.

Next, we were served sumac elote (my favourite), a deliciously herby rice topped with peanuts, and crunchy kimchi equal parts tangy and hot. The fried chicken arrived warm and comforting with a satisfying crunch and a sweet and tangy raspberry hot sauce. We washed it all down with an effervescent concoction of Earl Grey shaved ice.

Everything was tasty and messy. The presentation was artful, and dare I say, a perfectly Instagrammable, camera-eats-first opportunity. (I quickly snapped a few photos on my iPhone to share later.) Here lies, as Theodor aptly puts it, the humour of being able to shit out an artwork.

As we finished our final course, I began to realise that my expectations of being shocked or challenged seemed to have been misplaced in this case. This was by far the most deceptively normal menu STTK has concocted yet, a fact that the threesome explained was by design. “We’re cosplaying working in a kitchen”, Salvör Menuez laughs. (However, despite their attempt at a more accessible entry point to their transgressive culinary world, previous weeks’ dishes packed a fiery kick that left some dinner guests perplexed and panting, Okoyomon tells me.)

While to the dining hall’s patrons, it appeared like a regularly functioning restaurant experience, at Unclebrother, the experiment has less to do with the cooking than with the time spent in between: exploring the grassy riverside, floating in the current, making ceramics with Fairclough in the studio beneath the house, and yes, developing recipes. On the back end, it was a lot more open-ended for STTK.

“We’re not trying to be a successful restaurant; that’s not interesting to us”, says Salvör Menuez. “We want to push the understanding of what you’re going to eat to a point of growth rather than being exclusionary”, they explain. “Food is a medium that everyone should have access to. It has a real capacity for healing and there’s so much that is broken in food systems in the world.”

There is something both primal and post-apocalyptic about the way flavours, textures, colours, and shapes mingle on a STTK plate. Previous dining experiences have taken place in unconventional spaces—in art galleries, event venues, homes and outdoors—and have featured a dizzying array of foodstuff. Menus have listed edible dirt, honeypot ants, pig hearts nestled in orchid flowers or fermented with sourdough, entire pigeons brined in Alligator pepper and tied up in bondage, signature frozen ball gags made from cold-press juices. To eat an STTK meal is to engage in a psychosexual performance, a ritual of submission, dominance and, lastly, consumption. Table settings have included dirt, feathers, rocks, gynaecological tools and an antique gurney. Once, a banquet table was transformed into a runway for the designer Telfar. At any given dinner, guests might feed each other or be fed from a cloaked hand in a glory hole. In what can be described as decolonising cooking, expectations are flipped, fears are confronted and new concepts of eating are introduced.

“We usually ask people to do a couple things that probably aren’t a part of anybody’s culture, to deregulate these dinner party customs a little bit”, Theodor laughs. For one meal, they made really long spoons and asked guests to feed each other. The prompt was a response to the allegory of the long spoons, which tells a story of heaven and hell where “in hell you’re trying to feed yourself, but you can’t get it into your mouth because the spoon is too long, but in heaven, you use the spoons to feed each other”, Theodor explains.

As they plan out their respective practices, STTK acts as a protective membrane that nurtures and preserves the artists’ wildest ideas. The loose structure and spontaneous programming means that the next meal could be anytime and anywhere, whenever the right opportunity presents itself within their busy schedules. Regardless of when and where STTK will materialise next, it is certain to continue exploring new ways to highlight and challenge what it means to break bread. “Formal dining customs are learned. They’re very culturally specific. They’re political. You may not be conscious of it, but you know how to sit at a table, you know how to use the fork”, offers Theodor. But what if, just for a night, you could forget?

Written by Meka Boyle