There are few more intimate spaces than the bath. Submerged in water, leaving the bather naked and vulnerable, it is no surprise that it is a setting that has inspired more than a few iconic horror films, from David Cronenberg’s Shivers to Hitchcock’s iconic Psycho.

In Japanese architecture, the private space of the bathroom has historically rarely been incorporated into the compact design of the private home. Instead, communal bathhouses for centuries shifted the private act of washing into the public realm. It is a tradition that transforms the intimacy of solo bathing into a closeness that is shared. Known as sentō (銭湯), these bathhouses continue to serve an important social and symbolic function within Japanese society, although their numbers are dwindling.

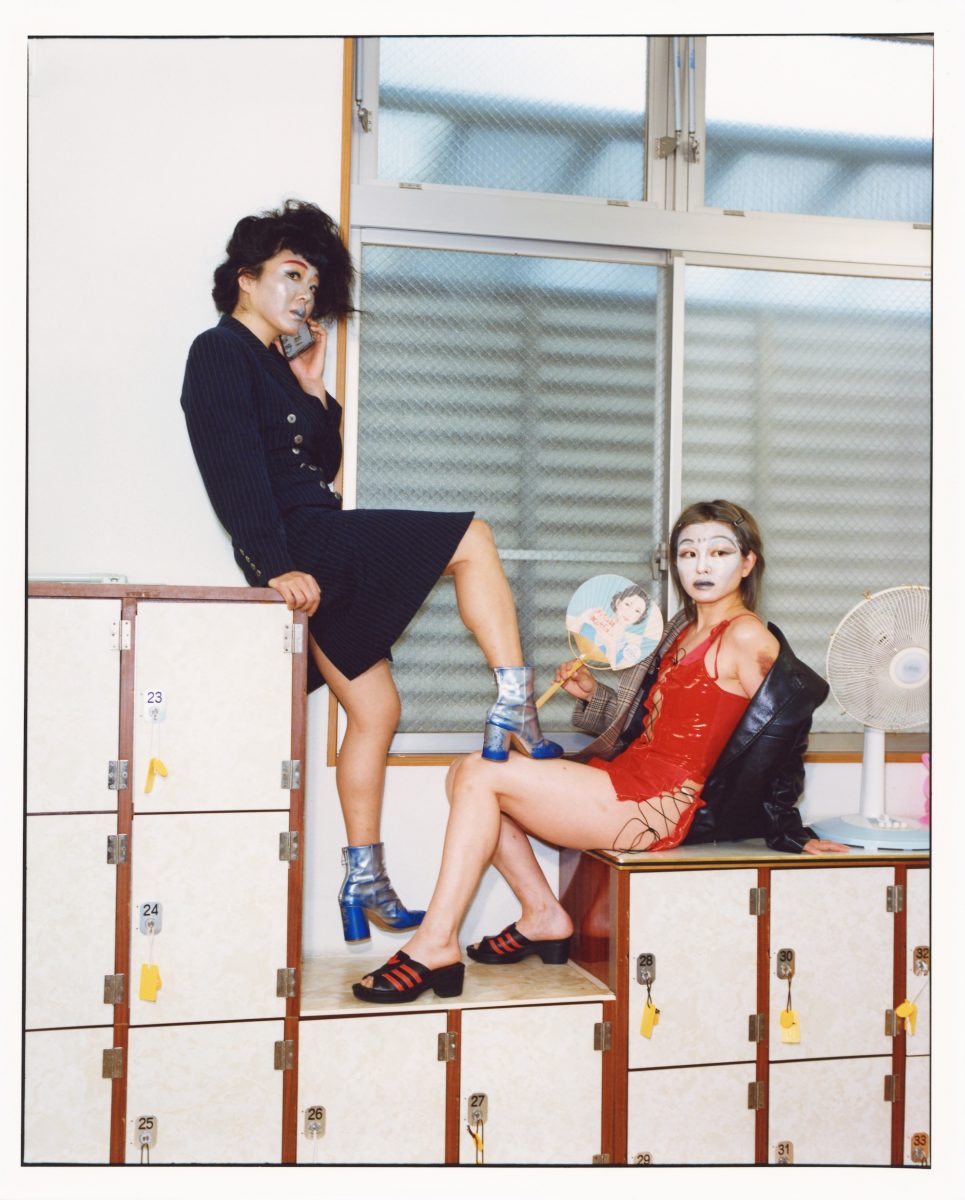

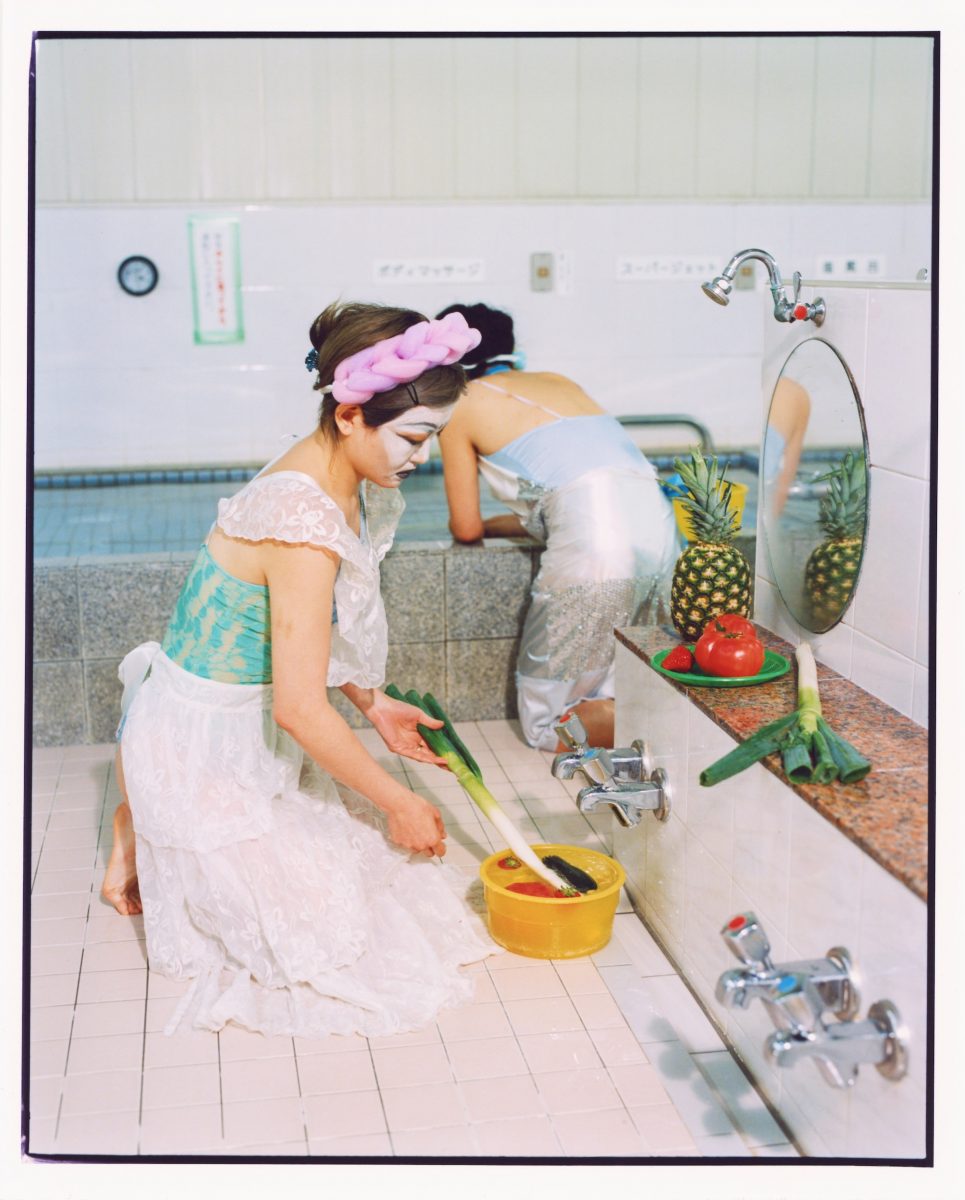

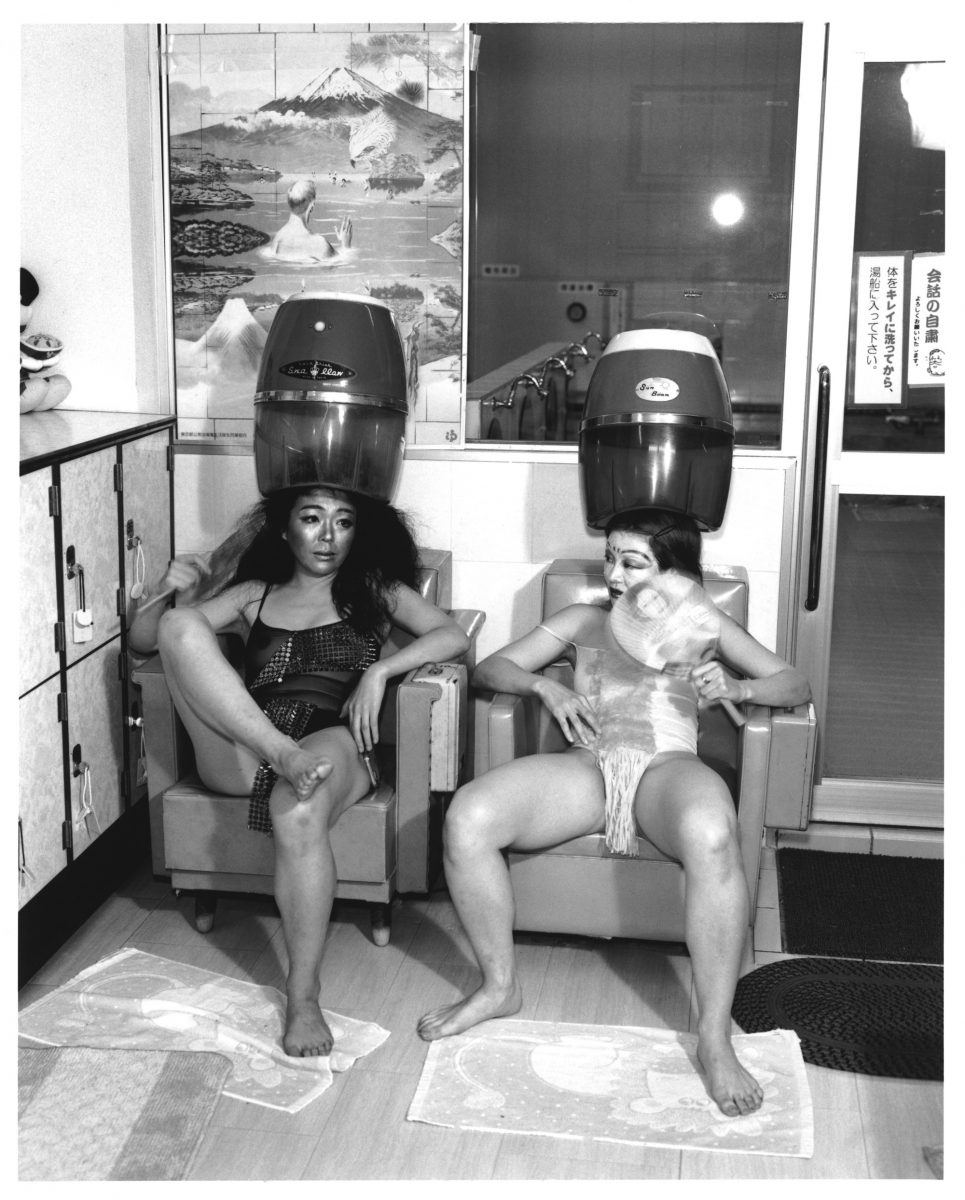

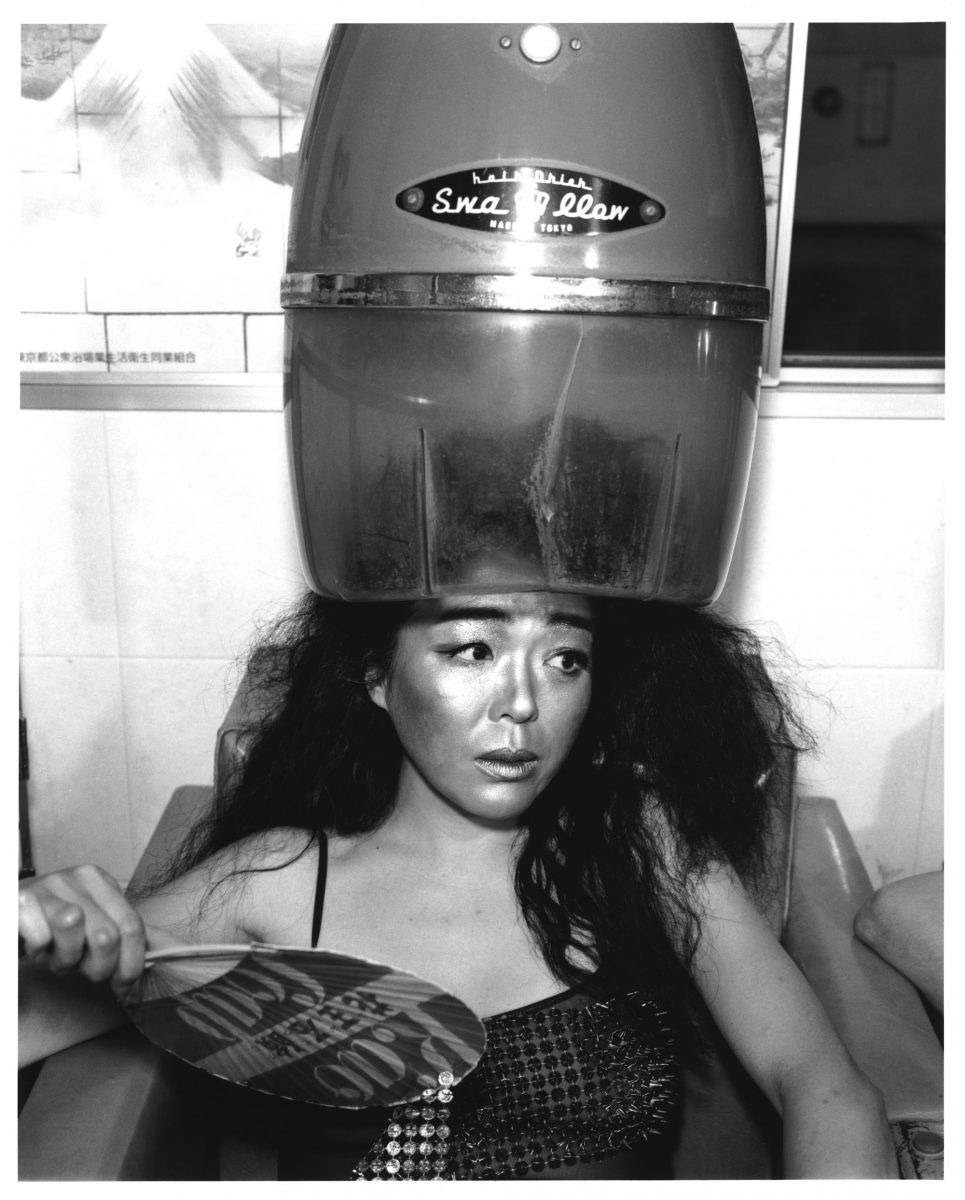

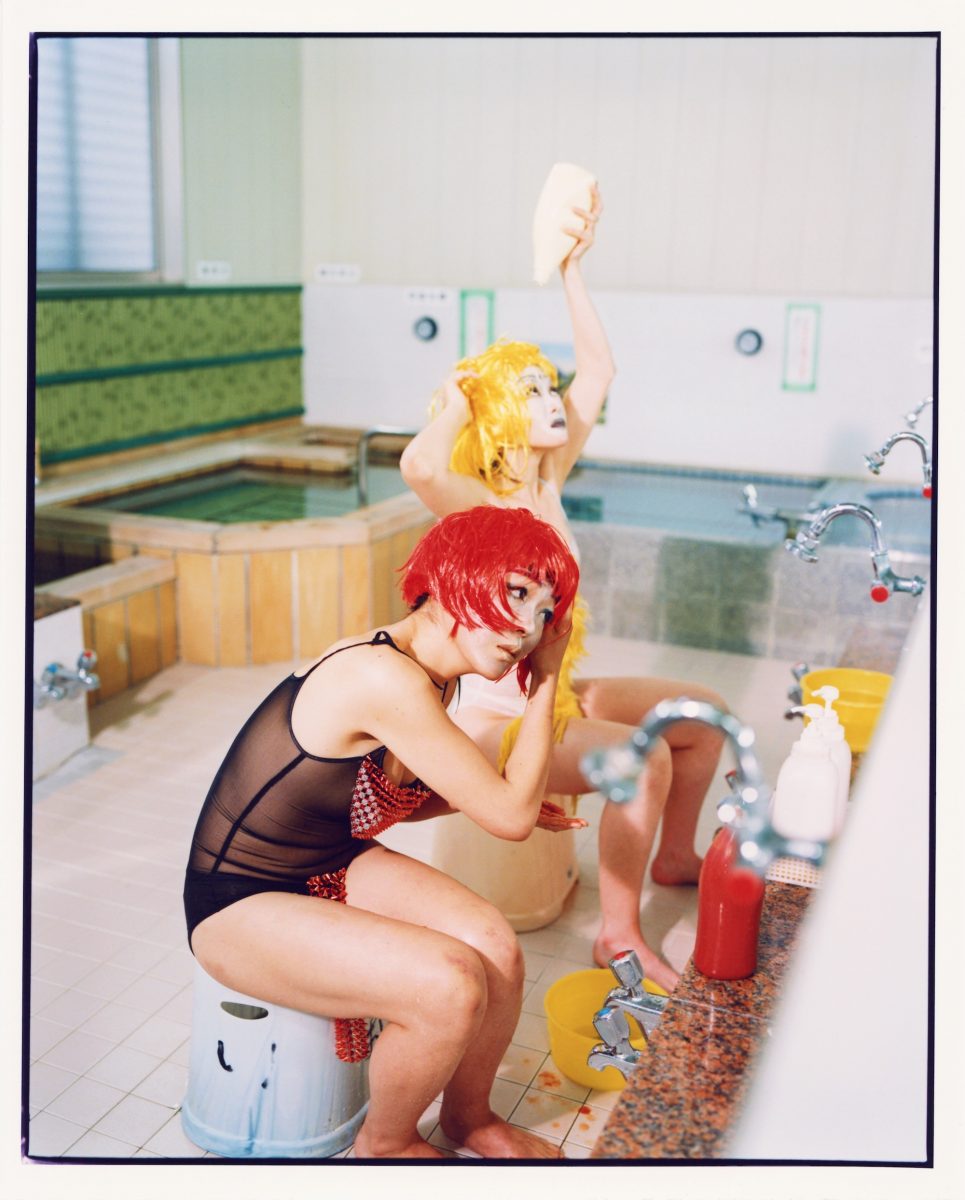

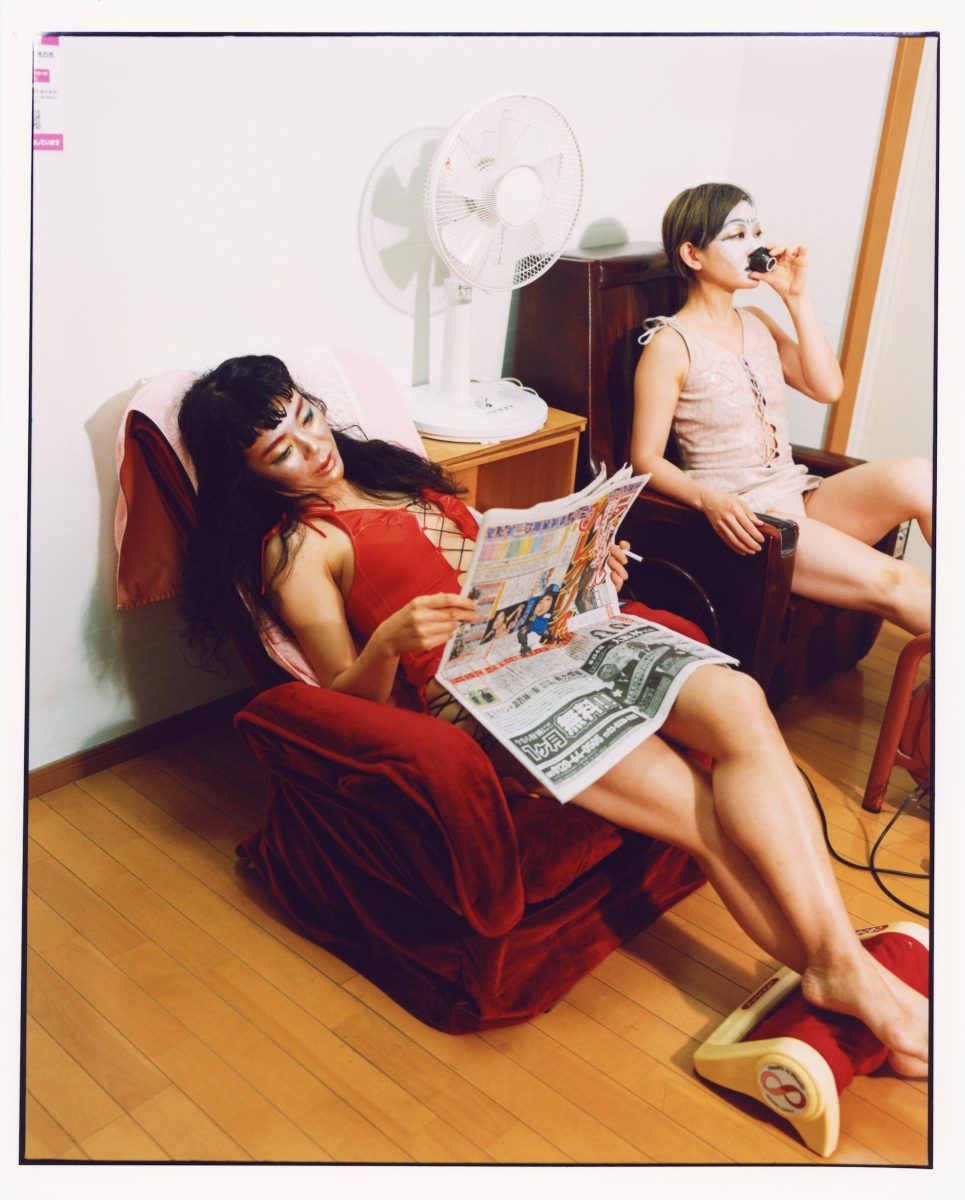

A new photographic series, Assholes, by the artist Motoko Ishibashi, created during the pandemic in collaboration with artist Urara Tsuchiya and fashion photographer Yuto Kudo, sees the Japanese bathhouse reimagined and destabilised. Ishibashi and Tsuchiya raucously make themselves at home in the politely tiled changing areas, locker rooms and pools, with increasingly absurd results. They play tennis across a row of sinks, and light cigarettes in loungers. They drink sake with relish and pose in high-heels on mosaics and massage chairs.

“They raucously make themselves at home in the politely tiled changing areas, locker rooms and pools”

Sentō are frequently defined by their strict rules, from gender segregation to etiquette on indoor shoes and showering before entering the baths. The trio playfully subvert these guidelines, sporting an array of colourful wigs, mesh bodysuits and face paint before the lens. In one shot, Ishibashi and Tsuchiya studiously type on laptops even as their bare legs are submerged in water. It is a surreal send-up of a relentless culture of around-the-clock work, made worse in the digital age, and arguably worse still under the conditions of the pandemic.

In Mieko Kawakami’s recent novel Breasts and Eggs, a pivotal scene takes place in a Japanese bathhouse. A chance encounter between two friends dissolves into an hallucinatory meditation on gender, mirrored in part by the strict rules and segregation applied to the ritualistic act of washing within the sentō. “I caught a stray homunculus by the neck and tickled him. I told him that he shouldn’t be there. This bath was for women,” Kawakami writes. “But the rest of them cried out ‘THERE’S NO SUCH THING AS WOMEN’ and squirmed their little bodies. They sang those words over and over. They didn’t care…”

“Their actions once inside the bathhouse are as surreal as they are sexualised”

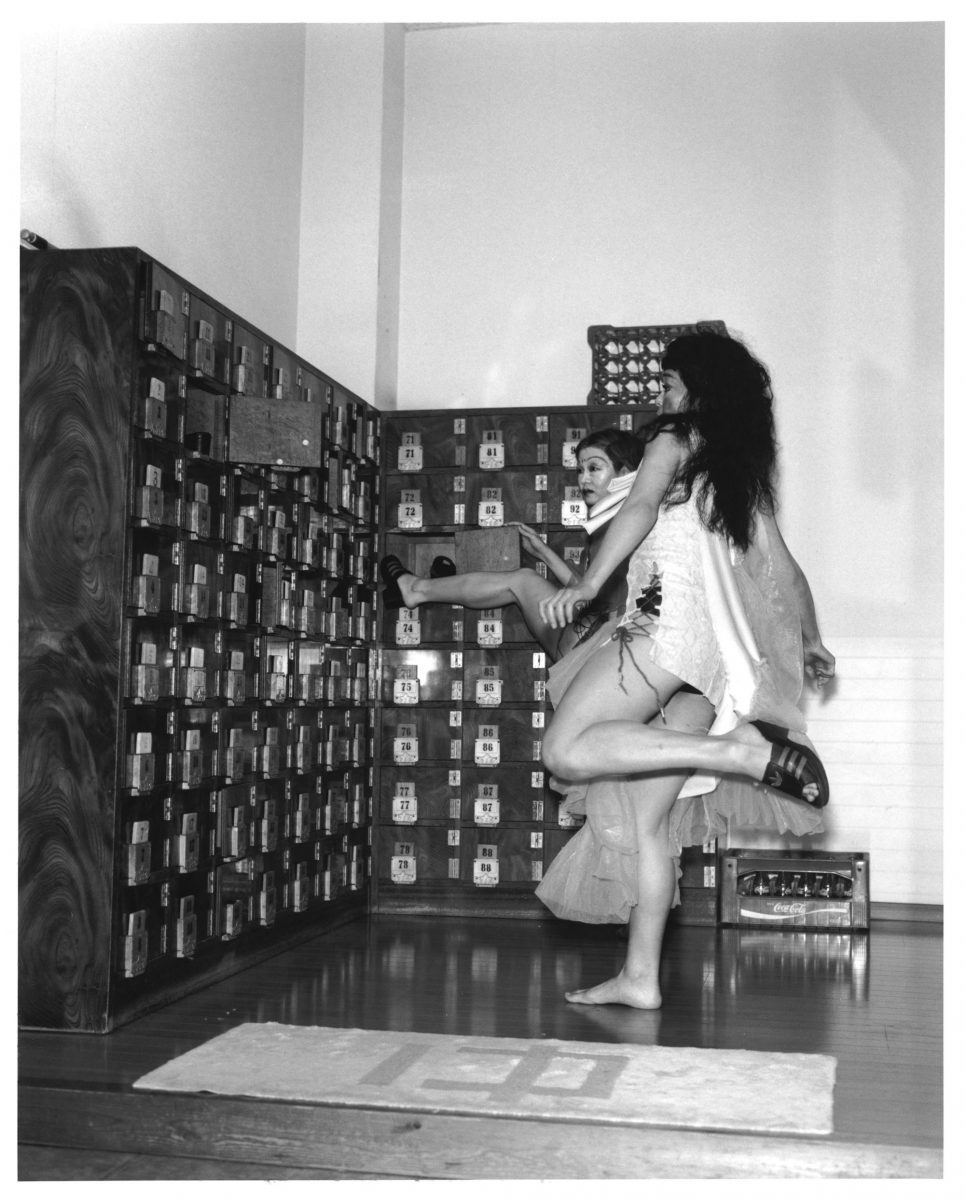

Ishibashi’s vision is equally antagonistic when it comes to gender, subverting not just the hallowed spaces of the bathhouse itself but the question of female agency within the narrow strictures of tradition. The artist and Tsuchiya are shown in one image to crawl on hands and knees from the street and into the bathhouse, as if collapsing beneath the weight of these careful boundaries. Their actions once inside the bathhouse are as surreal as they are sexualised, while their costumes both mock our expectations of femininity and amplify them to the point of instability.

While undoubtedly imbued with the humour of melodrama, these photographs raise darker concerns about what constitutes womanhood, laced with intimacy and rebellion. In a space where nude bathers usually congregate, Ishibashi instead inserts characters adorned with painted faces and lopsided wigs, breaking with convention to imagine a world where the delineation of strict binaries no longer applies.