In 1991, Catherine Opie took photographs of her close friends dressed in male drag and posed against a bright yellow backdrop. The resulting series, Being and Having (1991), had a subtle emotional power that gained her global notoriety. Each photo is taken at such close proximity that you can just about make out where the glue is beginning to lift on the edge of each moustache. The portraits are alive with familiarity, and it seems that there is a world of in-jokes that Opie is willing to share with the viewer if only they are willing to look. But there is also something desperate and searching about them, as though Opie is saving every detail to memory. Given that Opie had been forced to watch her community devastated by the HIV/AIDS epidemic, it makes sense that her photography would preserve every out-of-place eyebrow and stifled laugh that the camera might allow her to keep.

It is a wandering practice that has taken Opie on a series of road trips across America. In 1998, she lived in an RV for three months, shooting Domestic (1998), where she photographed lesbian families at home. Then, In 2007, she took to the road again for three years, shooting High School Football Players (2010). And again, in 2020, when Opie travelled to Richmond, Virginia, where she shot monument/monumental (2020), her reckoning with the aftermath of the Black Lives Matter protests. The great American road trip is a recurring theme. When I ask her about this, she laughs, “America is a vast landscape with profound differences of ideology depending on where you go, and I can’t just sit in LA and point my finger at what I think might be happening. You know, I can’t be a great disruptor without actually disrupting from within, so to speak.”

© Catherine Opie. Courtesy the artist, Regen Projects, Los Angeles and Thomas Dane Gallery. Photo: Evan Bedford

But why America? “Because I want to argue with it,” says Opie, “I’ve never thought of America as a great democracy, and a lot of other people from other countries will argue with me about this, but I don’t think that great democracies are built on War.”

Opie grew up in Sandusky, Ohio, with a father who owned the largest collection of Republican political memorabilia in America. There is a sense in which Opie is building her own archive in opposition. High School Football Players (2010) documents the heroes of high school football teams from a series of small towns in America. Despite the proud stances of the subjects in the photographs, there is an eye-watering vulnerability there. Some have a smattering of acne, and

others wear a slightly too big football jersey. Small reminders that these are just young boys in a floodlight stadium.

“I wanted to show the vulnerability in these young boys that is always dismissed. We think of them as hyper-masculine and heroic. They are basically being trained as soldiers. I wanted to show that, no, there are long gangly limbs and awkward smiles,” says Opie.

Roland Barthes coined the term “punctum.” He describes this as: “That account that pricks me (but also bruises me, is poignant to me).” It is that small detail that makes the photograph meaningful, and that meaning can appear after the fact, in the knowledge of the events that followed.

Opie tells me that years after the series was shot, she received letters from the mothers of the boys she had photographed, thanking her for taking their sons’ pictures. They had since died in Afghanistan.

In the three weeks leading up to the presidential election in 2016, Donald Trump tweeted the term “Drain the swamp” no less than seventy-nine times. The slogan stayed with Opie, who, in 2020, travelled to Louisiana to capture the great unknown of the American marshland. If the general consensus at the time of shooting Rhetorical Landscapes (2020) was that the swamp lands were a perilous place where life goes to die, the series was an invitation to viewers to reconsider. The swamp in Rhetorical Landscapes (2020) looks serene. The trees are bleached, and the leaves are deadened grey, and there is a sense that this swamp land isn’t something threatening- but rather something vulnerable and worthy of protection. It’s the same tender gaze that Opie turned to the mini-malls of Los Angeles in Mini-Malls (1998) and Elizabeth Taylor’s empty room after her death in 700 Nimes Road (2014).

In conversation, Opie notes that, since shooting at the swamp, an algal bloom is now threatening to eclipse its existence. “People will repeat certain sentiments without ever having a basis of understanding for what that thing truly is,” says Opie “I don’t believe that images can change things politically. But I believe in the creation of dialogue. I don’t think I can save anything. But I can certainly have a conversation about the times we are living in.”

© Catherine Opie. Courtesy the artist, Thomas Dane Gallery and Regen Projects, Los Angeles.

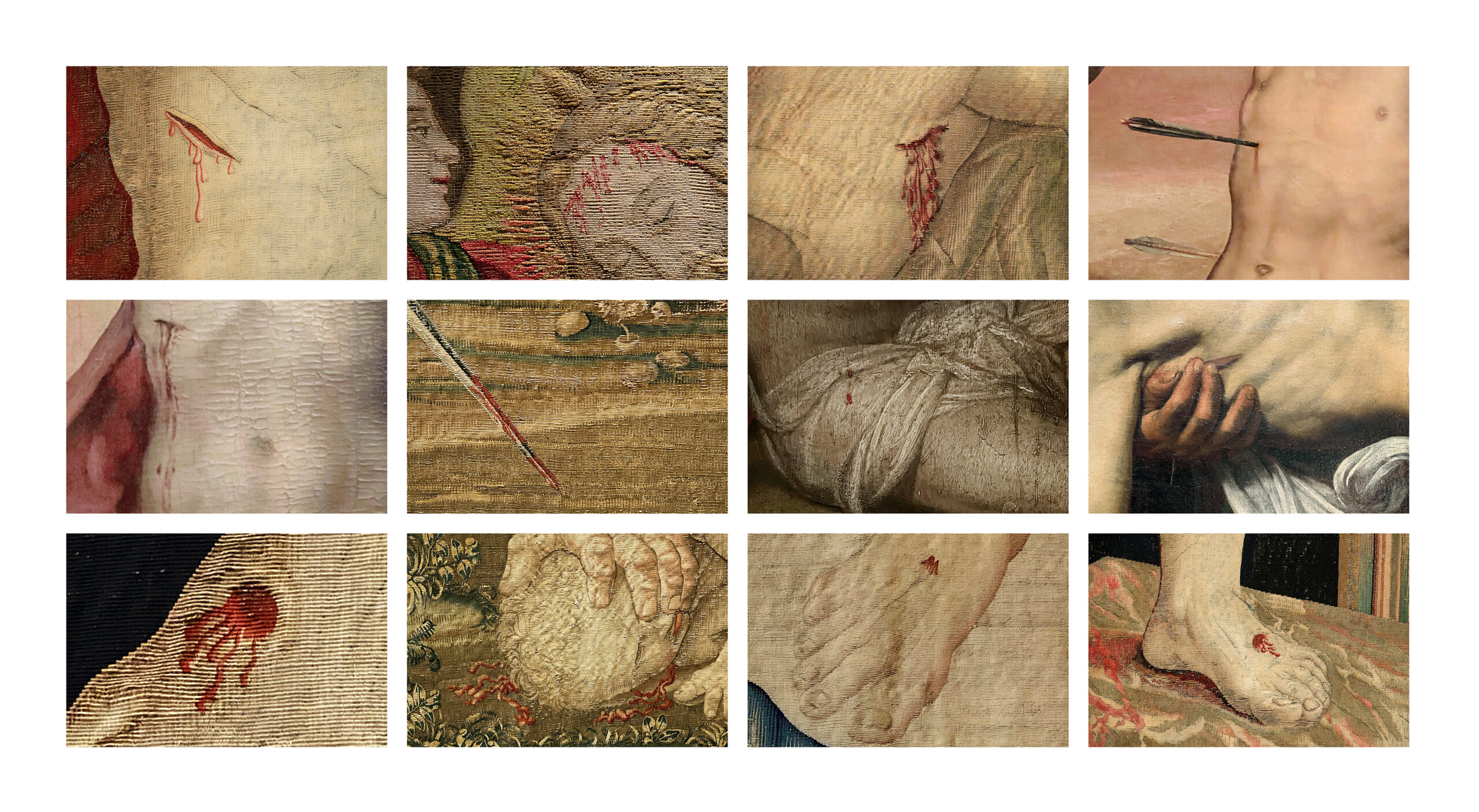

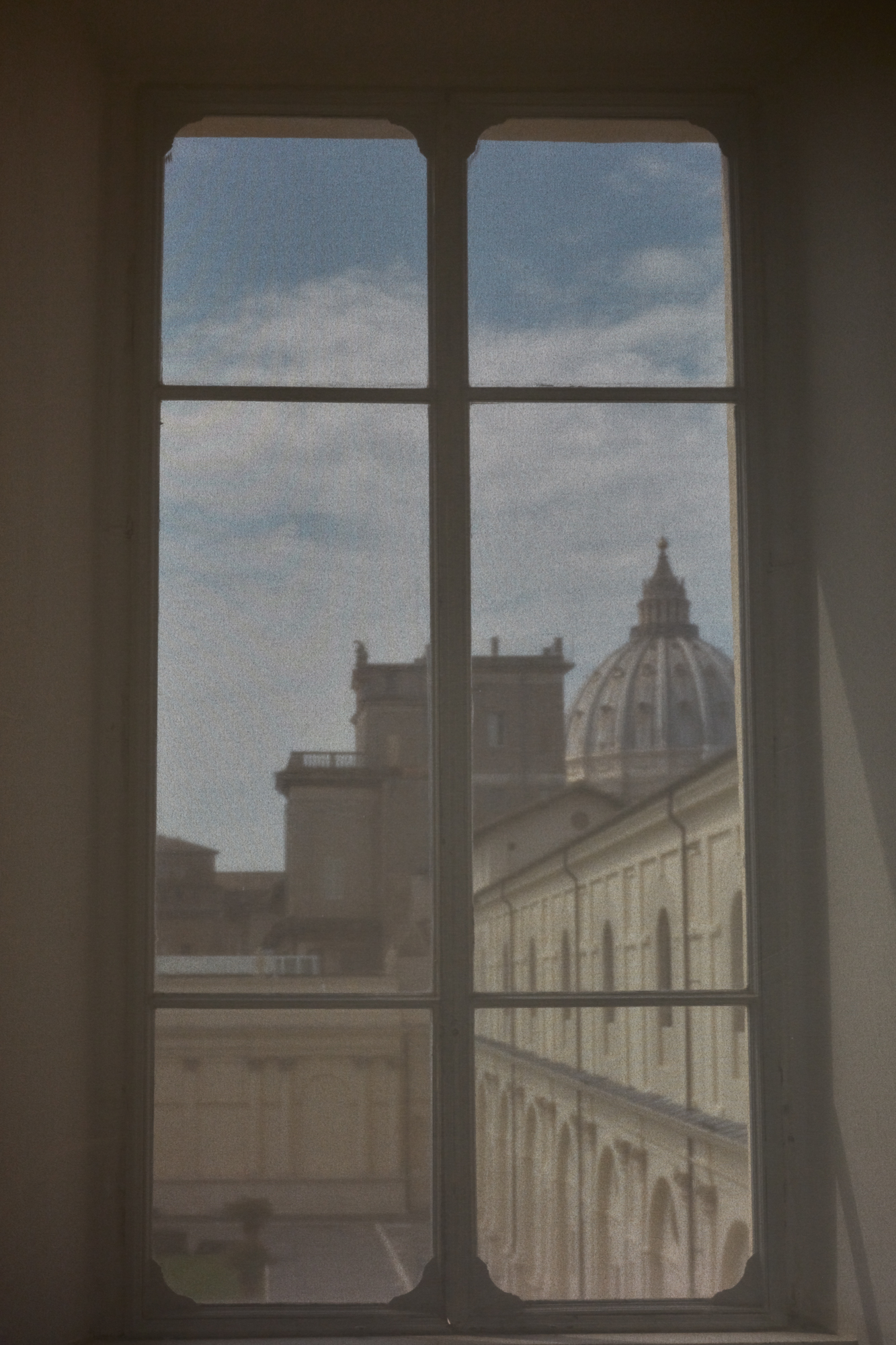

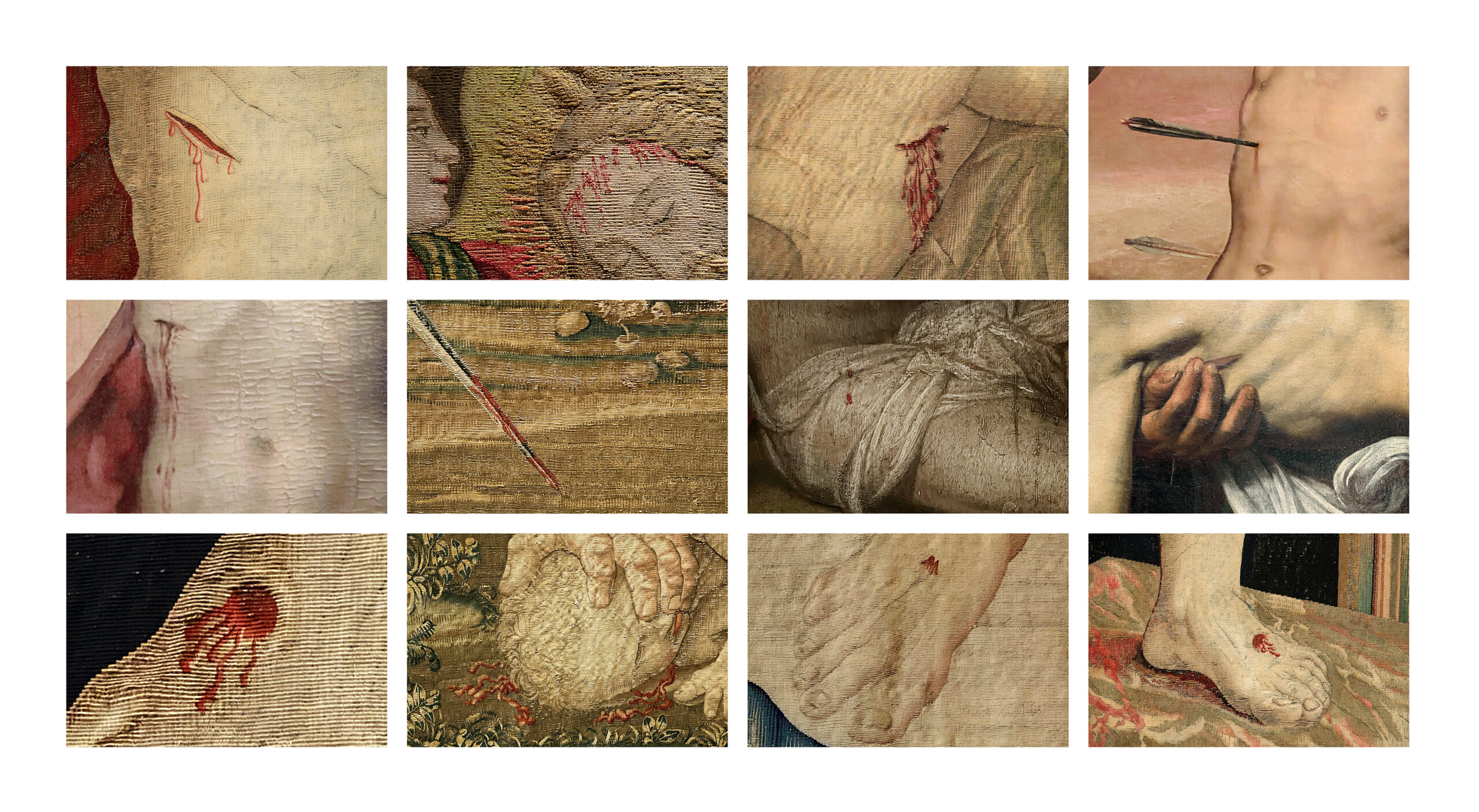

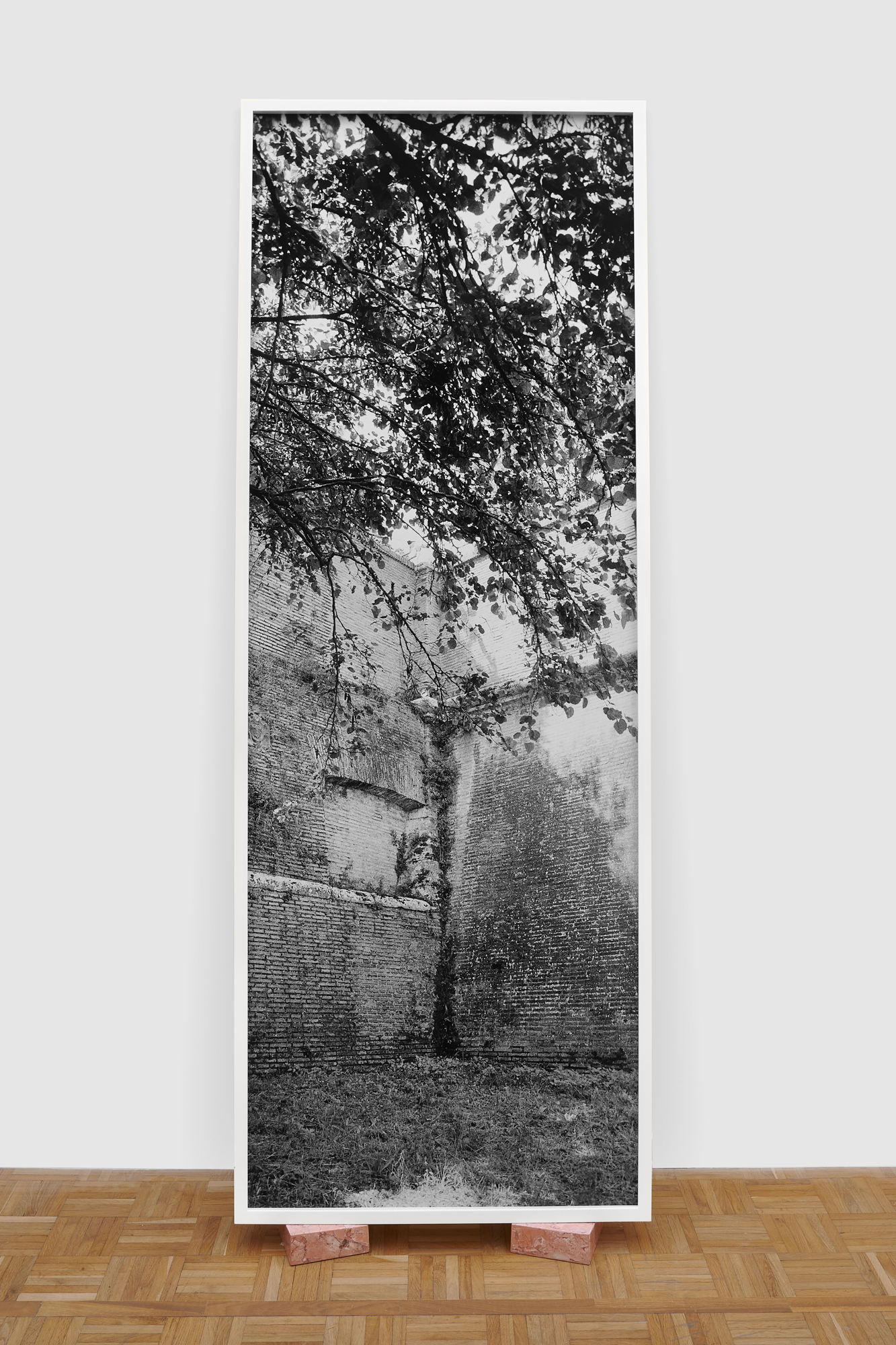

In her most recent series, Walls, Windows and Blood (2023), Opie has taken on an even more formidable opponent. She has turned her lens to The Catholic Church. The images were shot during her six-week residency in Rome with the American Academy and picture the architecture of The Vatican and the paintings hung on the walls of its museum. The walls of The Vatican itself are steep and formidable, an impenetrable fortress. The windows are covered by gauzy blinds and intricate metalwork that prohibits the outside world from looking in. Blood drips from Jesus on the cross, saints are stabbed, and even children aren’t spared from grisly acts of torture. They suffer valiantly. “I went through the museum, and I photographed, with three different cameras, every bit of blood that I could find,” says Opie. The series was shot during the pandemic, and there were no hordes of visitors in the space. She was free to wander the empty grounds, working out lighting and mapping out what it is to take in The Vatican, then distilling it to create a taxonomy.

© Catherine Opie. Courtesy the artist, Thomas Dane Gallery and Regen Projects, Los Angeles.

“I was thinking about the dialogue right now around transparency in institutions,” says Opie “so the windows were the perfect place to begin. And then the walls are about being on the outside looking in. But the blood is, quite honestly, about the fact that I am always arguing with different museums who want to put warning labels before the Self Portrait series. Because I don’t think there is anything wrong with my self-portrait.” She is referring to, of course, her now infamous series of self-portraits, which includes Self Portrait/ Cutting (1993), Self Portrait/ Pervert (1994) and Self Portrait/ Nursing (2004). In Self Portrait/ Cutting (1993), we see Opie’s back freshly bloodied by a childlike etching of a happy home which has been engraved into her skin. In Self Portrait/ Pervert (1994), Opie sits in front of the camera, topless and masked in a latex hood. Her arms are lined with needles, and the word pervert has been freshly carved into the flesh of her chest. The last in the series, Self Portrait/ Nursing (2004), shows Opie topless again, but this time nursing her son Oliver. The faint scar of the word pervert still proudly sprawled across her chest.

The battle between queer artists and imposed censorship is nothing new. Opie mentions Jesse Helms and his attack on Robert Mapplethorpe’s work in 1989 and David Wojnarowicz, who was famously under siege from the conservative American Family Association in 1990 and was then censored again by The Smithsonian in 2010. The Smithsonian’s secretary, G.Wayne Clough, ordered for a short video excerpt of David Wojnarowicz’s A Fire in My Belly (1987) to be removed, claiming it was anti-Christian. “This is exactly why I carved the word pervert onto my chest”, says Opie. “I was like, well, they’re going to call me that anyway. I’m just going to go ahead and label myself and let them deal with that. But really, who is the pervert here? My relationship to ideas of perversion is all done consensually and with the most loving care. Not everyone can say that. And the Catholic church is the one of the worst.”

© Catherine Opie. Courtesy the artist, Thomas Dane Gallery and Regen Projects, Los Angeles. Photo: M3Studio.

Ultimately, Walls, Windows and Blood (2023) is Opie taking aim at the hypocrisy of it all. “They will automatically put a warning label on my self-portraits because of homophobia,” says Opie, “Yet you can go through The Vatican’s museum and find paintings of children being stabbed with bloody knives with no warning sign, no trigger warning. I know it is not a photograph but still a representation.”

Opie references the Pope’s refusal to apologise in 2018 for the Catholic church’s role in Canada, where 150,000 First Nations Inuit and Métis children were taken away from families and forced to convert. They were horrifically abused, and many died.

“How can you talk about God and then have these kinds of structures?” Opie asks.

Opie’s own history with religion is fraught. She describes her grandmother as a staunch Southern Baptist who once, upon finding out that Opie was gay, made her visit her home solely to tell her how disgusted she was by her decisions. And then, five minutes later, asked Opie to leave. “Every Sunday, I used to go to Sunday school. I had to wear these little white gloves and a little dress,” says Opie, “and at some point, I just decided, sorry, I am not performing femininity for you anymore.”

It’s hard to imagine that anyone would be up for the task of trying to argue with Catherine Opie about her identity, but even in recent years, she has dealt with the unwarranted opinions of the church. “I have had students that have made work in relation to praying for me,” says Opie, “because they think I am so abject that I need to bring Jesus into my life.” She also discusses the recent sale of her apartment in Los Angeles. “We were in the process of selling it, just after I shot Walls, Windows and Blood, and guess who the two top bidders are? A lesbian couple and the catholic church. The catholic church won out because they are so obscenely wealthy. It’s like a joke- Catherine Opie walks into a bar and has to decide between the Catholic Church and the lesbians.”

I ask her if she is religious. “No,” she says, “I’m an atheist. But there is a spirituality in me, so I don’t know if I can say that. I have my finger on the pulse a lot. And I am always watching the world in a very careful way. I try to be really careful with people, you know, it’s important for me to be careful in this world and to be a caring person. I want to try to help people. But I don’t do any of this because of some belief system. I do it because humans should do that for one another.”

Words by Emily Burke

Catherine Opie’s Walls, Windows and Blood is on display at Thomas Dane Gallery, Naples