The studio lights beat down on Twin Peaks actress Mädchen Amick. Brow furrowed, glossy lips clamped shut, her jaw and tongue work furiously to tie the cherry stem inside her mouth. Rick Dees—host of the US chat show Amick is a guest on—leers at the 19-year-old. “Mmmh!” he repeats, feasting on the image of her as the audience whoops.

The year is 1990 and the cherry is in its heterosexual prime, oozing glitz and casual objectification. Immortalised by the Twin Peaks scene

in which Sherilyn Fenn as Audrey Horne places a maraschino cherry between her bright red lips, eats the flesh and ties the stem in a knot, this party trick drips with oral-sex innuendo. This is just one of many erotic fantasies imposed upon the fruit, however. Over the past 600 years, the cherry has been rendered, revered, plucked, popped, won and lost—and it is primarily men who have authored its iconographic narrative.

The patriarchal virginity fetish that ensnares the cherry has roots in Christian imagery. The cherry tree accompanied medieval depictions of the Virgin Mary and the miracle of immaculate conception, and this motif persisted in Renaissance art. In Titian’s Madonna of the Cherries (c.1515) the infant Christ holds a sprig to his mother’s face as she gazes down at him. In Quentin Matsys’ Madonna and Child Kissing (c.1525–1530), the lips of mother and child mimic the two cherries held delicately in Mary’s hand. “The cherry showed up in the Virgin and Child scenes not just as a symbol of Mary’s virginity but as a symbol of Christ’s suffering and the blood of Crucifixion,” says art historian Abigail Susik. “It’s a particularly mixed and uncomfortable symbolic metaphor: it correlates to the inherent violence of lost virginity, with the hymen being pierced.”

“As an erotic symbol, the cherry has lost its lustre. The peach has taken the crown of fruity sex symbol”

Euphemisms of virgins ‘popping’ or ‘losing their cherry’ stem from the early 1900s in England, though it was during the 18th and 19th centuries that the ripe cherry became synonymous with juvenile femininity. In John Russell’s Little Girl Showing Cherry (1780), James Earl’s Lady Mary Beauclerk (1793–94), and John Everett Millais’ Cherry Ripe (1879), prepubescent girls with porcelain skin and plump cheeks offer up punnets to the viewer. These portraits idealise youthful innocence, yet the cherry-virgin paradox is a disturbing reminder of sex to come. This knotting together of the cherry and child-like femininity peaked in Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita (1955), which is littered with references to “cherry-red nail polish” and “cherry pies”. In Stanley Kubrick’s 1962 filmic adaptation “cherry pie” becomes a metonym for Lolita herself.

As an erotic symbol today, the cherry has lost its lustre. Pop art cherries, cherry-print dresses, cherry keyrings: they’re more tacky than tantalising. One would hope that the cherry’s fading sex appeal indicates a societal distancing from the archaic virginity fetish, but there are other forces at work. As beauty standards pivot from breasts to booty, the peach has taken the crown of fruity sex symbol.

View this post on Instagram

“The peach got its renaissance with the emoji because it looks like a butt,” smiles Swedish photographer and model Arvida Byström, who interrogates femininity in digital culture. Her pink-inflected Instagram account features still-life compositions of fruit, flowers and smartphones (a post-Internet take on the Dutch Vanitas tradition) as well as peaches and cherries dressed in tiny mesh knickers. In 2017 she staged an eight-hour live performance in which she tied cherry stems with her tongue: a nod to Audrey Horne and a comment on how this fantasy of femininity has been reproduced to the point of exhaustion.

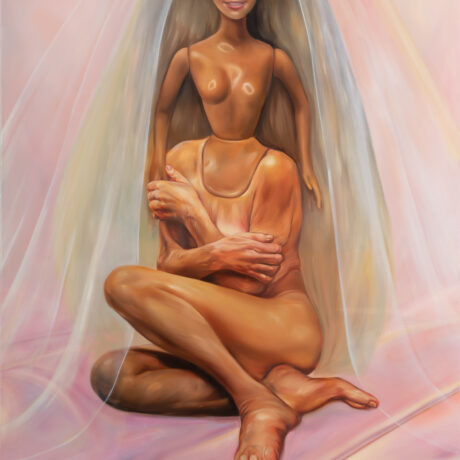

A teenager in the 2000s, LA-based sculptor Nevine Mahmoud also inherited the cherry’s cultural baggage. “I remember seeing cherry-print underwear everywhere, which I wasn’t allowed to have and didn’t really know why I wanted,” she reflects. “I guess it was a kind of flag to say that you are sexually aware but also chaste or protected somehow.” Today, her stonework transforms cold, hard materials into succulent fruits and body parts. Dwarfing the viewer with its stainless-steel stem, Cherry Viçosa (2019) is wrought from 300lbs of Portuguese pink marble, but looks irresistibly soft to the touch, the dimple where stem meets flesh, the smooth cleavage down its surface. “I don’t see the cherry as one particular body part but more as a feeling of the body, of two fleshy parts meeting and pushing together,” Mahmoud explains.

“These portraits idealise youthful innocence, yet the cherry-virgin paradox is a disturbing reminder of sex to come”

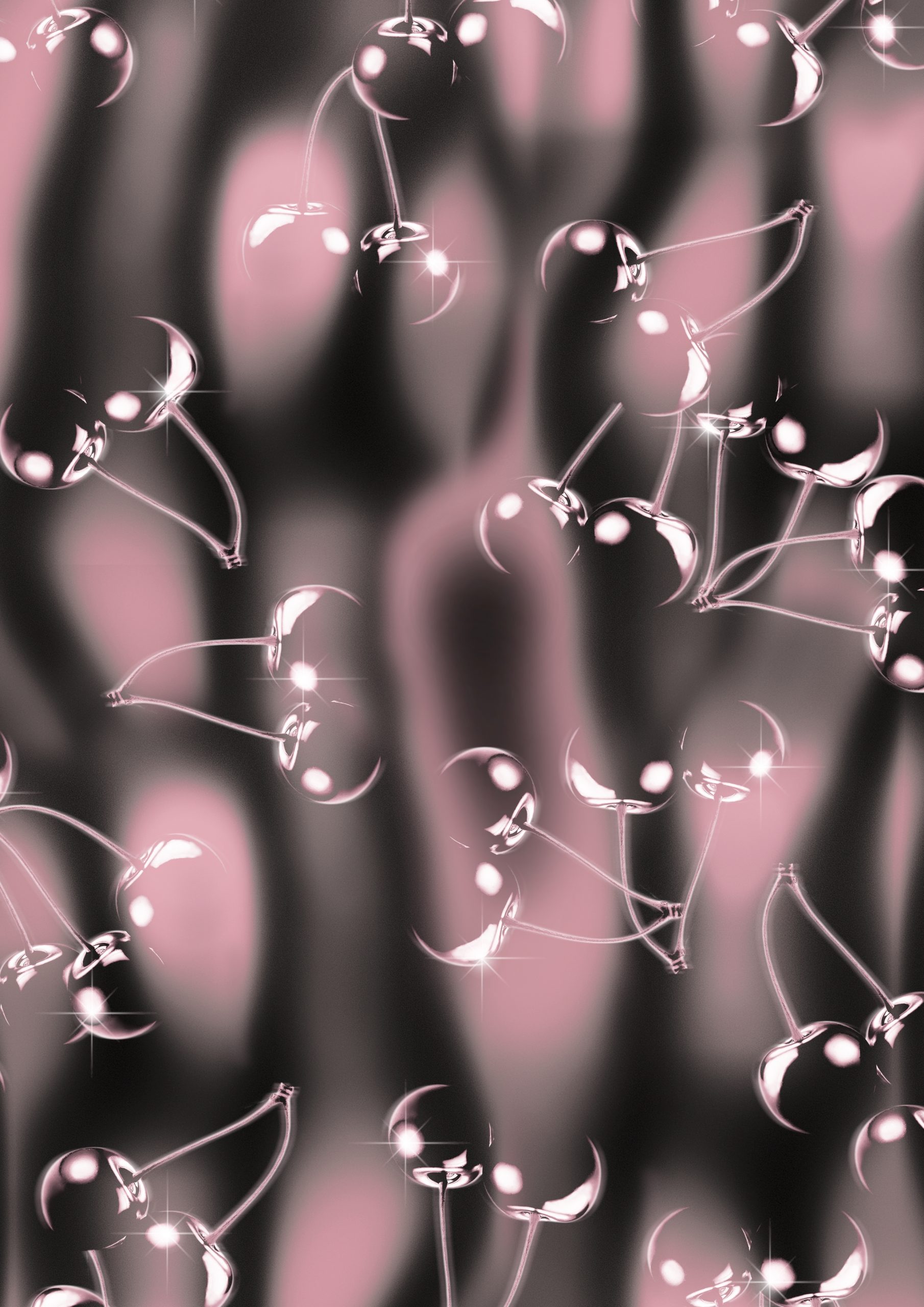

The seductive gloss of Mahmoud’s Black cherry (2018) is reflected in English designer Rhianna Ellington’s Cherry Bomb print, named after The Runaway’s 1976 hit. Inspired by 1980s airbrush art, she exaggerates the wetness and sheen of the cherry’s surface in her digital artworks and textile patterns, satisfying what she describes as “an increased desire for tactility in design”. The jet-black colour of Cherry Bomb shifts the motif away from its more complicated blood-red connotations.

“When Beyoncé sings “turn that cherry out”, the cherry signifies the clitoris, transforming it into a symbol of ecstasy”

Moves to reclaim the cherry are also being made in music. When Beyoncé sings “turn that cherry out” in Blow (2013), the cherry signifies the clitoris not the hymen, transforming it from a symbol of pain to a symbol of ecstasy. Through her song Cherry (2018), British-Japanese pop star Rina Sawayama chose to come out as pansexual. “You looked at me with your girl gaze,” sings Sawayama, and asks her crush to be her “cherry”. Filmed with an all-queer cast, the music video focuses more on cherry blossom than the fruit, with Sawayama covered in Sakura petals as a princess from Japanese folklore. In queering the cherry, Sawayama finishes what Katy Perry started in 2008 when she teased, “I kissed a girl and I liked it, the taste of her cherry chapstick”.

The cherry has long been heralded a female sex symbol, but it was merely stamped with an idea of female sexuality, pivoted around male pleasure. These artists are giving the fruit the cultural reset it deserves, refiguring it not as an object to be ‘popped’ and ‘lost’, but as a pleasure point to be found.