Born to Pakistani parents, Furmaan Ahmed is a multi-disciplinary artist, choreographer, set designer and image-maker from Glasgow. They relocated to London to study at Central Saint Martins, widening their practice to commercial and artistic photography, before returning to Scotland last year. Their practice foregrounds imaginative world-building within trans and non-white communities.

For ‘State of the Nation’ they photographed their fellow artists in Glasgow, Chester and London, as part of a special series in which artists discuss how living in the UK informs their work and their ways of thinking about unity and identity, home and heritage.

I’ve been freelance since I left Central Saint Martins last summer. I’ve worked both commercially and in the music industry, whereas before I’d been working as an artist. I say ‘artist’ because these labels are very separate for me. They’re different cultures in the way work is made and the conversations that happen.

Life felt very regimented in London. I worked with Interscope Records and went to the US to collaborate for David LaChapelle and Willow Smith. The scale was so big, a lot of the time it’s quite impersonal. There’s a different kind of person who lives in London, especially in education and the arts. It all comes down to wealth and privilege. I got to London because I was funded by a charity in Scotland. At CSM it became very apparent that I shouldn’t have been in that space. I realised how closed those doors are. My move back to Glasgow came out of me questioning whether I actually belonged to that community in London, which is all about hustle.

- Ewan; Sgaire; Mum(left to right). Courtesy Furmaan Ahmed

I grew up on the southside of Glasgow in Pollokshields, which was a predominantly Pakistani and South Asian community. It was very closed off: I didn’t have any white friends until I went to secondary school. Since I’ve returned, I’ve had to keep stepping back to realise there has been this huge cultural renaissance in Glasgow.

“My move back to Glasgow came out of me questioning whether I actually belonged to that community in London, which is all about hustle”

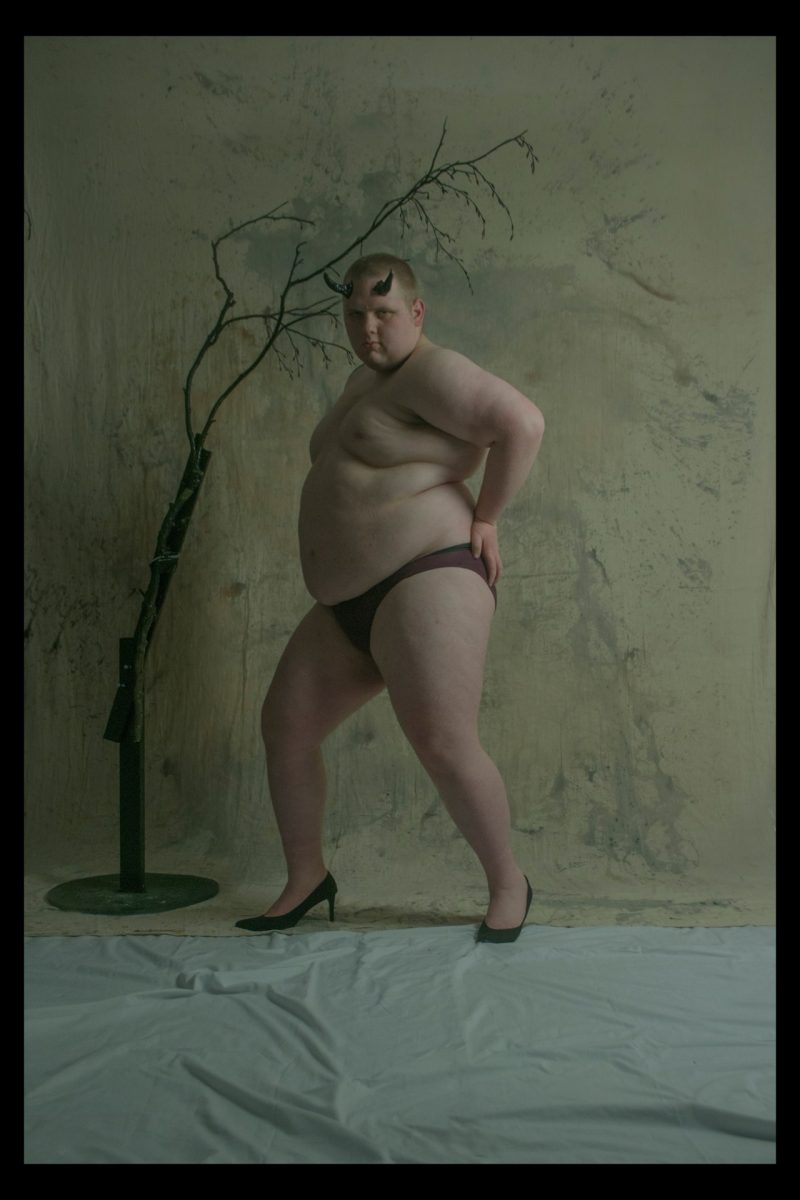

All of my work at the moment has been with Black women or people of colour. And even just other trans people. I’ve been able to sustain a living here through that, which is a rare and special thing. I’ve been working with the Vogue Scotland Ballroom scene. We just created a nine-hour film of unchoreographed dance, just using your body to different kinds of music, all derived from trans and Black people.

I feel more comfortable here now. I can walk down the street presenting how I want to and not feel as terrified as three years ago. There are other brown people in the community who are just as queer and visible as I am.

Historically in the Pakistani community, there has been a culture of insularity and not reaching out to community spaces. But recently, there seem to be so many Pakistani people using these places in Glasgow: aunties sitting in a coffee shop next to someone with orange eyebrows or something! It’s very nice to see that. It’s almost utopian.

“I feel more comfortable here now. I can walk down the street presenting how I want to and not feel as terrified as three years ago”

So many binaries are already placed on us, especially saying that we’re ‘second generation’ immigrants. We should be thinking further ahead than these national identities, because they’ve hindered us historically.

I’m displaced in so many ways, from my gender to where I’m from. I see myself as a trans person and a non-binary person, but in a way, I don’t think that it’s me being displaced in my own body. It’s the world’s parameters which are displaced.

My work is about difference and world-building, so people tend to let me do what I want. The most fun and fruitful part is the collaboration. New worlds and ideologies cannot rely on just one person. That itself is a Western idea: the concentration of ideas and power on the individual rather than collective experience. We need to decolonise artmaking so that it’s more emotionally led. That ethos should carry forward into productions, sets and live events.

“I don’t think that it’s me being displaced in my own body. It’s the world’s parameters which are displaced”

Art is a healing process. It’s for me to talk to others who have the same kind of secret language that any kind of diaspora person has. We should be focusing on commonality. That’s what I try to do in my work: to create that space where we’re able to think about a future that’s more inclusive and less bordering.

As told to Ravi Ghosh, Elephant’s editorial assistant

This article appeared in Elephant 46: Autumn Winter 2021, available to buy here