There was a time I used to go to the library regularly. As a child, my Saturday morning ritual was going to the overly-chlorinated local swimming pool where I’d pick up a verruca and then head on to the local library to pick up some books. It was a very dowdy library in the very dowdy town of Melksham, Wiltshire, and it smelt of mothballs and cardigans. But the absolute silence was sobering and exciting. They had teenage magazines you could leaf through (contraband at home). There were equally piquant Judy Blume books in the “young adult” section that I’d quickly thumb through to try to find the raunchy bits and swear words.

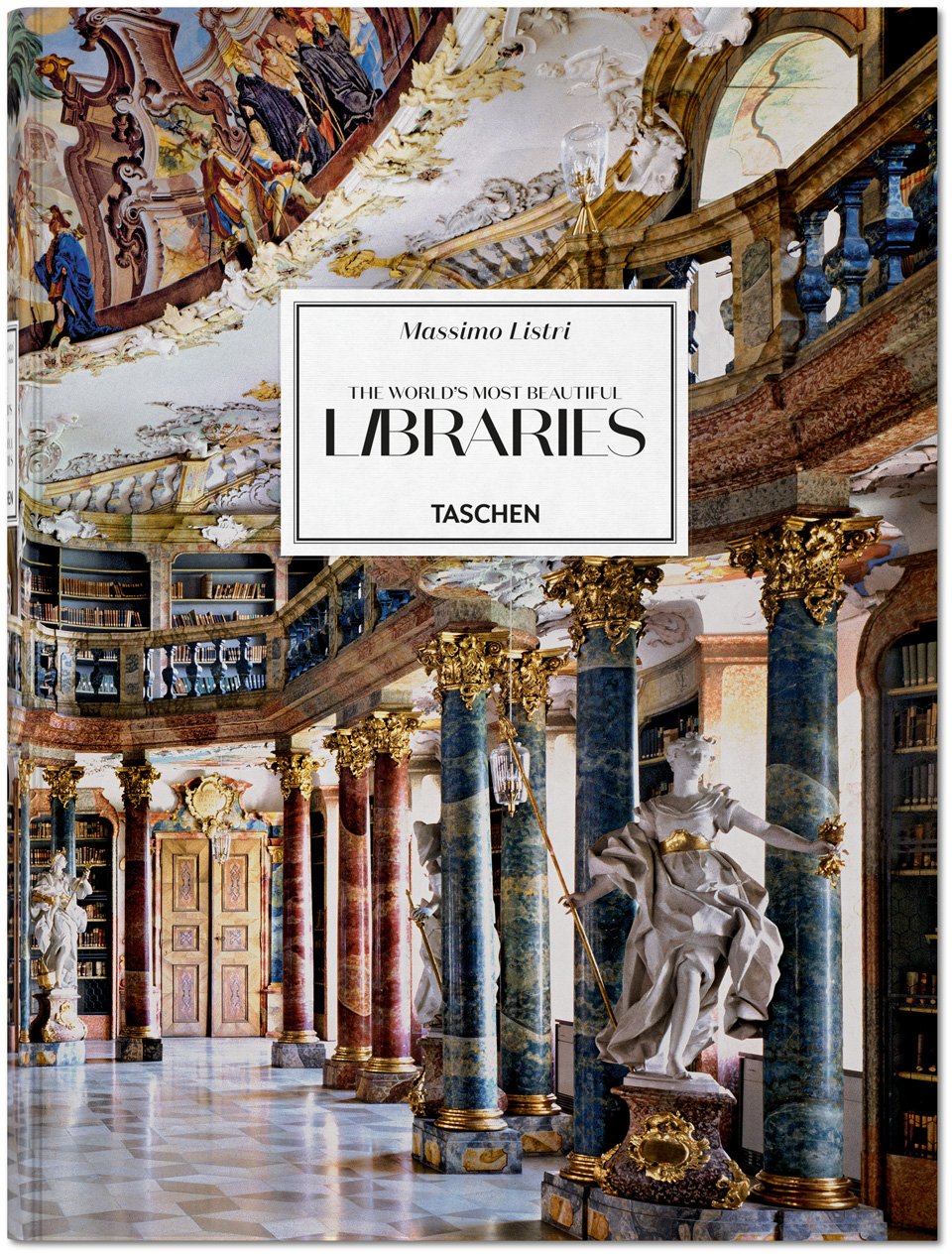

“What it lacks in portability, it makes up for in opulence: appropriate to convey the grandeur of the homes to tomes around the world”

The books were all laminated and still bore those stamps on the inside front cover, so you knew how many hands had held that book before you. Some of them had coffee stains or the tell-tale ripples of being dunked in bathwater. There was nothing more satisfying to me then than proudly piling up a stack of books, all that knowledge (this was pre-internet, of course) waiting to be sucked from their pages (and rapidly forgotten). I took out books on random subjects I knew nothing about, strange eras in history or autobiographies of people I’d never even heard of. It was free, after all, and there was nothing else to do.

At some stage of life, the hushed thrill of libraries turns into a plaintive, anxious quiet—that of the student poring over a book before an exam. I was lucky enough to frequent the Taylorian Library as an undergraduate, the beautiful, historic library next to the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford. It smelt more of old wood and leather. The desks were huge and sumptuous, huge windows to daydream through, lovely little lamps to light your pages. A good friend found it the best place for an afternoon nap, with a copy of a Cervantes book as a pillow.

If you could capture a library in one book, Massimo Listri might have done it. Before we get into the details, let’s just pause a moment to take in its size. It is the biggest book I’ve ever seen. It’s so huge and heavy it comes with its own carrying case. It’s basically a table.

But what it lacks in portability, it makes up for in opulence: appropriate to convey the grandeur of the homes to tomes around the world (by which the book really means, Europe and the Americas). The earliest libraries in Europe still in existence now date back as far the Middle Ages—that’s forty-five generations ago, as Georg Ruppelt points out in an opening text, Memory of the World (also appearing in German and French). “The definition of knowledge and scholarship includes the criterion of unlimitedness,” he writes. “Scholarship knows no national or ethnic borders and no boundaries of religion or language; the bounds of ethics and morality are those it sets for itself. Other limits are imposed upon it only in times of darkness or by inhumane systems.” The same principles, he argues, apply to libraries—books might be bound, but the library’s collection should be boundless: “Libraries are repositories of the facts of the real world as well as of the many alternative worlds of the imagination.”

Detailing a brief history of the evolution of libraries from the ancient to the present day—and even a projection of libraries of the future, and how we have assuaged our need for information and knowledge over the centuries—the essay is a fascinating account of human history and the complex duality of knowledge and power (many of these libraries were originally constructed as part of monasteries or churches, for example). It is also, of course, almost absurdly geeky. It is a book that celebrates books, architecture and, emphatically, the crucial experience of reading. It doesn’t matter what you read, perhaps, but what happens while you are reading.

“The essay is a fascinating account of human history and the complex duality of knowledge and power”

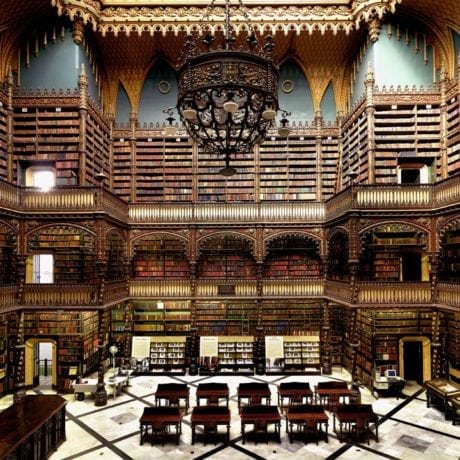

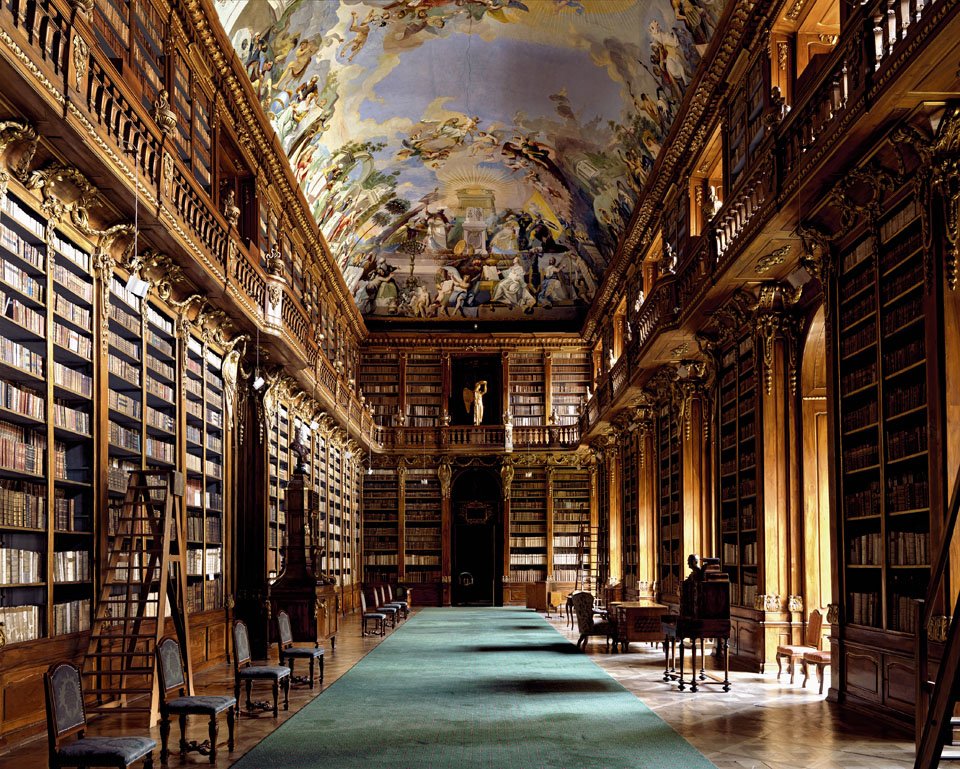

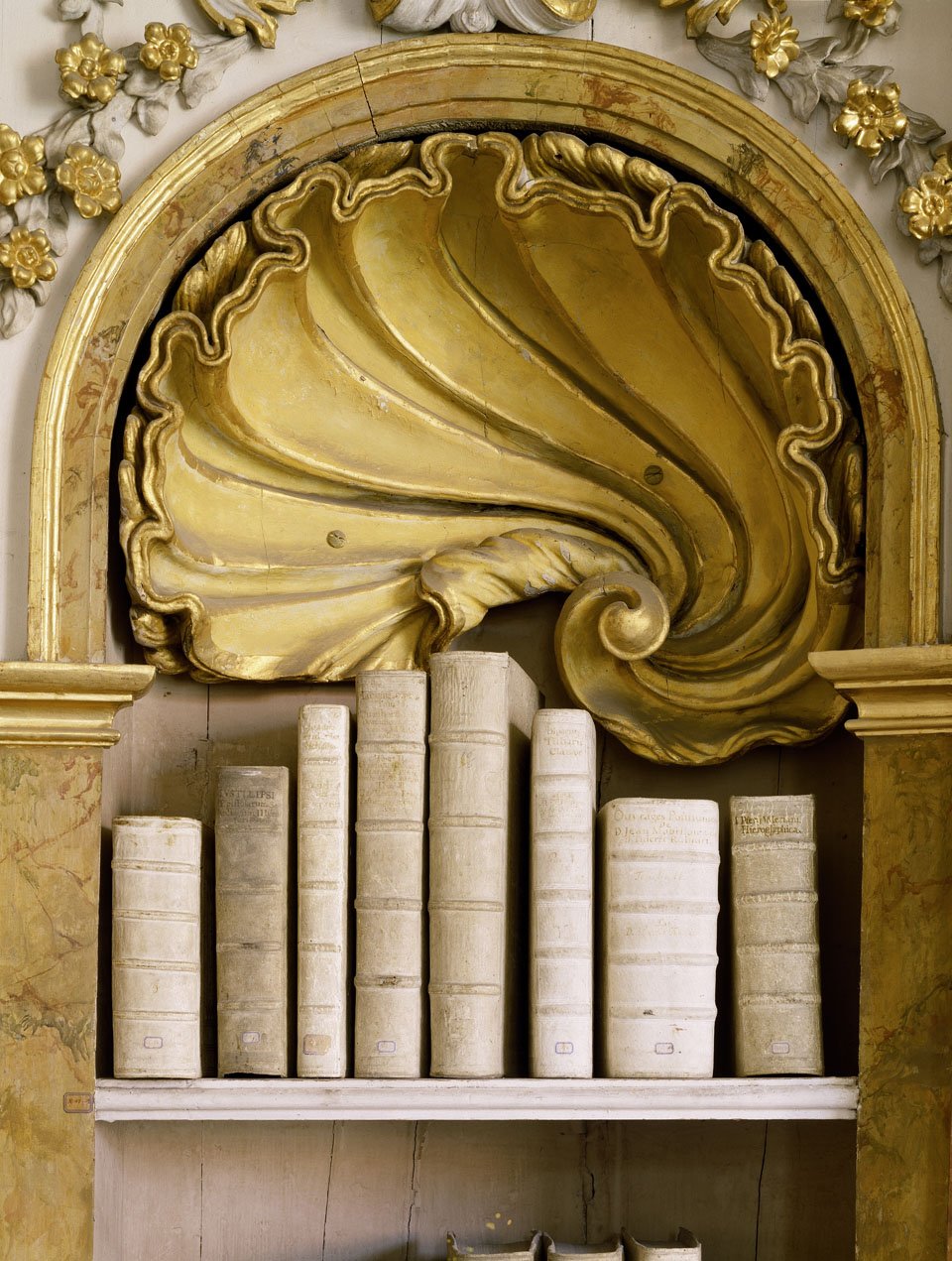

What follows on is more accessible: pages upon glossy pages of gorgeous, full-bleed photographs (of epic proportions) documenting breathtaking libraries such as the Biblioteca do Convento de Mafra, located in the baroque Palace of Mafra, Portugal. The rococo library, with its rose, cream and dove coloured marble tiles, contains more than 36,000 books—and homing bats, who protect the books from gnawing insects.

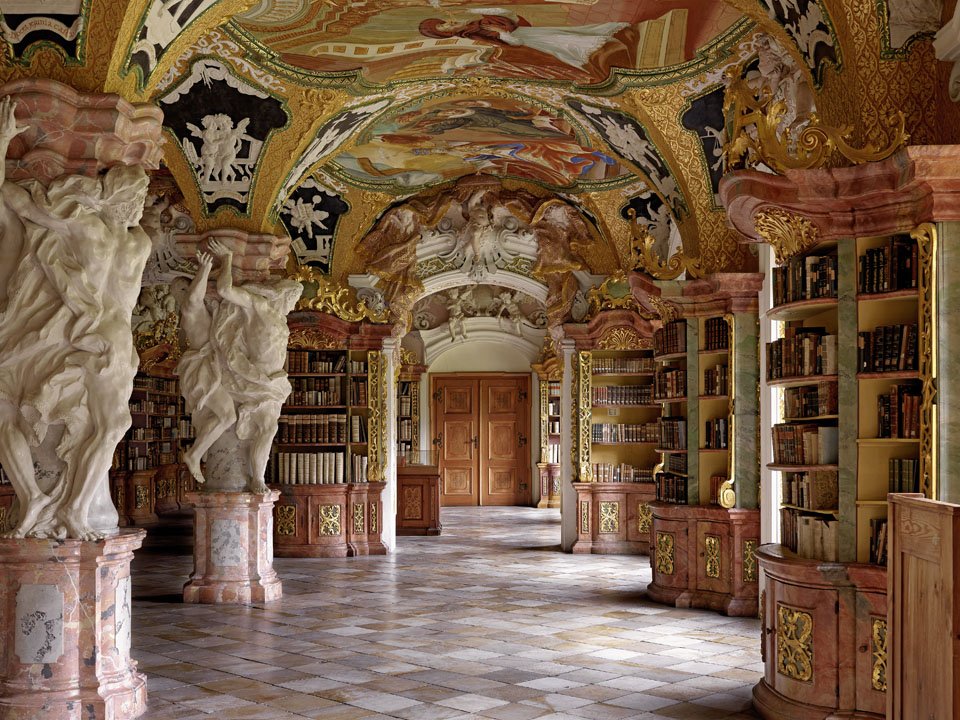

Another knockout is the baroque Klosterbibliothek Metten, in Lower Bavaria, part of a Benedictine monastery. The ceiling frescos were done in 1723, by Innozenz Anton Warathy, an Italian craftsman and painter. From the ornate to the humble, these large-scale photographs conjure the thing all libraries share: that meditative mood for quiet reflection, thinking and contemplation. They impose order. Not unlike an art gallery or museum, except libraries have more chairs.

The book begins—as I shall end—with a quote from Stockhausen, who described libraries as “well laid-out gardens, in which new owners spring up around us with every step, embellishing their surroundings and giving o the scent of pleasure”. As I remember the smell of that library in Melksham, I couldn’t agree more.