“I’ve never really looked back before, but now that I’ve done it, I’ve realised I’ve just gone full circle,” says Stephen Gill. “I’m just doing now what I did as a kid, messing around with microscopes and being obsessed with pond life.”

We’re discussing his retrospective at Bristol’s Arnolfini arts centre and though Gill is being typically self-effacing, there’s some truth in what he says. Born in Bristol in 1971, he’s showing work from an exceptional 30-year career, which has included exhibitions in many of the world’s leading institutions, and collaborations with writers such as Iain Sinclair and Karl Ove Knausgård. Taking over the entire gallery, Coming Up for Air: Stephen Gill, A Retrospective is a big show in every sense, including works that initially seem dazzlingly, restlessly diverse.

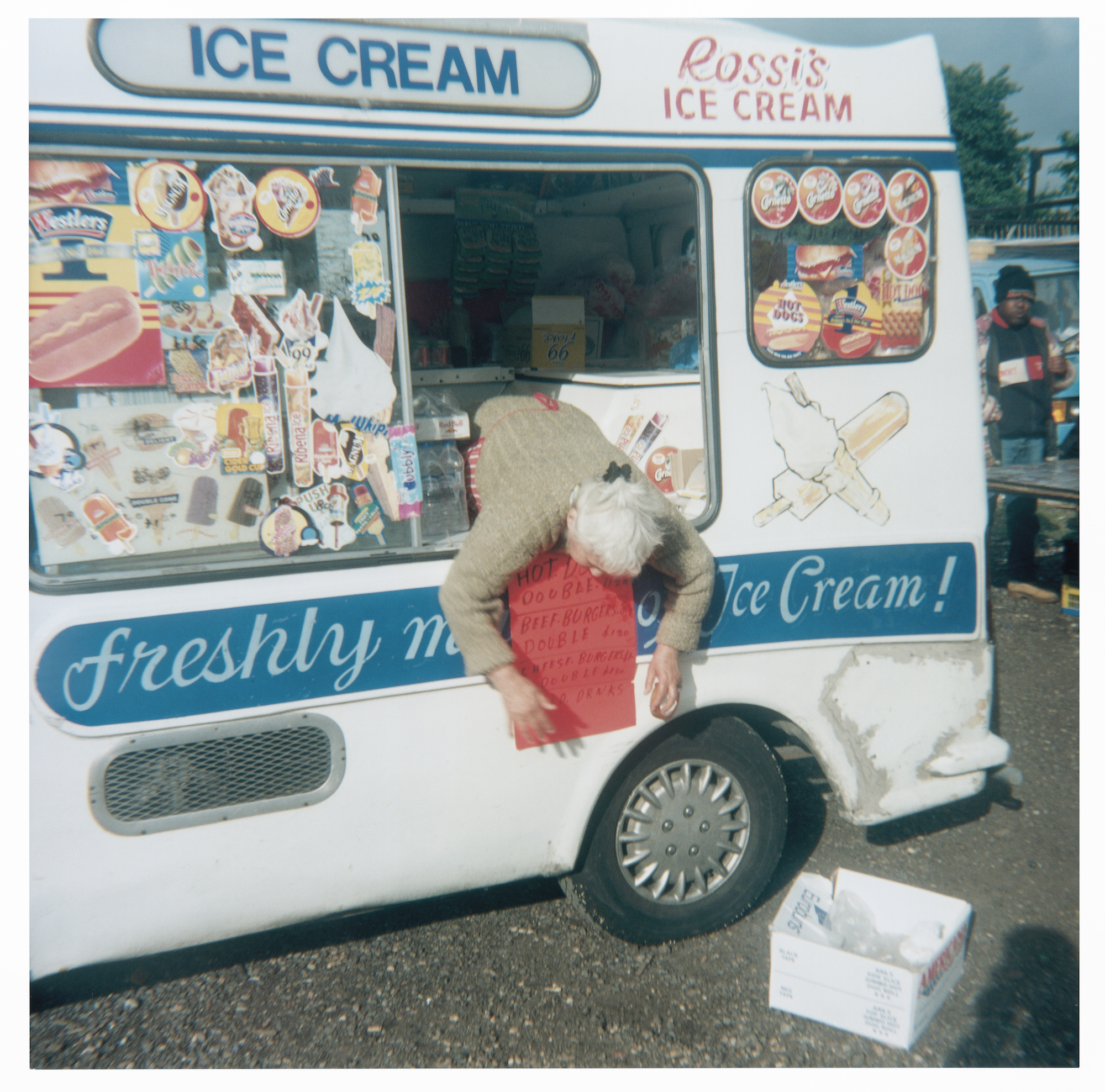

There’s the series Hackney Wick

, for example (shot from 2001-05) when Gill was living nearby, before the area was upgraded for the London Olympics and when a ramshackle market was in operation; Gill bought a cheap old Bakelite box camera from one of the stalls and used it to take the photographs. Then there’s Hackney Flowers (2004-07) in which he pressed flowers, seeds, berries and objects he had found locally and photographed them alongside his own images and ephemera. In Talking to Ants (2009-13), he inserted insects and objects directly into his camera, while in Coexistence (2011), he dipped his camera and prints into pond water.

“Photography so often tends to exaggerate or amplify, but I realised that, even if there’s less, there’s something amazing”

His award-winning project The Pillar (2015-19) shows birds sitting on a post in rural Sweden, where he now lives with his family. The birds were photographed automatically by a motion-sensor camera, triggered by their movement. Night Procession (2014-17) was also shot in Sweden with motion sensors, and records animals in the dark. Gill’s retrospective also includes his latest work, Please Notify the Sun (2020), in which he used a microscope to find strange landscapes inside a fish.

The Pillar, 2015-19

“In a way it was things that I hate,” laughs Gill. “I hate that stuff, optics and cameras and Googling how to do it. But I knew it would be quite remarkable to go on this journey, travelling inside a fish.”

The show also includes earlier and less well-known projects. There are classic black-and-white photographs from Poland (1996-98), for example, and there’s the quietly endearing series Trolley Portraits (2000-03), which captures older women in East London with their shopping trolleys. A Series of Disappointments (2008) shows still lifes of betting slips, folded and torn. Then there are the projects in which he buried prints in the ground, Buried (2005-06), or partly processed in energy drinks, Best Before End (2013). The exhibition also includes self-published books, because alongside all this Gill also set up a publishing arm, Nobody Books, in 2005, to handcraft his own photobooks.

It’s been quite a journey, but Gill says he’s grateful that photography “gave me a way to channel all that excess energy. It could have been a completely different story when I was a teenager.” He adds that he’s high spectrum ADHD: “It’s so good to be able to channel all your energy into something, and I’m still amazed I managed to turn my hobby into something I do for a living.”

- Hackney Flowers, 2011

- Talking to Ants, 2009-13

As Gill says, it all started when he was a boy, taking pictures of birds and pond life. Perhaps surprisingly, he never studied photography beyond foundation level, but he’s always taken it seriously. His father was a keen amateur and taught him how to process and print, and Gill worked for a local photography company while still at school, then at a one-hour photo lab after he’d left. He worked at the prestigious Magnum Photos agency from 1994-97, assisting photographers and processing black-and-white film. This is where the classic look of his early Poland work comes from, drawing from an older tradition of photojournalism.

“It’s nice to finally walk away from the work, the dialogue is between the audience and the work now”

Gill says it felt important to include this work in the show, but adds that it “probably says very little about Poland and much more about me wanting to be a photographer. They’re very classic so in a way they don’t reflect Poland in the mid-1990s. They’re more a search for something that’s in your head, without necessarily knowing what. Then I abandoned that and started to dismantle everything I knew.”

Hackney Wick is often picked out as the turning point, and while Gill doesn’t see it quite that way, he does remember it feeling “liberating”. Previously he’d been going out with something in mind, he says, whether it was the classic style of the Poland photographs or looking for women with shopping trolleys. For Hackney Wick the only parameter was the place, and that meant “the work was almost making itself”.

The camera he was shooting with had a plastic lens and lacked focus and exposure controls, so the resulting images are fuzzy and desaturated. For Gill, this “dialling down” of information was fascinating, particularly because it actually only added to the sense of place. “Photography so often tends to exaggerate or amplify, but somehow I realised that, even if there’s less, there’s something amazing,” he says.

“In a way it was things that I hate: optics and cameras and Googling how to do it…”

More recently, he’s seen that this was also the start of another ongoing interest, of finding ways to step back and let the subject take over, sometimes quite literally, by putting plants and insects into his camera, or letting the animals trigger it. Even so, his work has taken it out of him and these days, the 50-year-old says, he has to be careful about how much he does. In fact he’s been thinking he’s finished with photography, though he adds ruefully he’s been saying that since Hackney Wick

.

When I speak with him he’s feeling relaxed, pleased that his retrospective is on display after two years of hard work and taking the opportunity to take stock. “The [opening] weekend felt perfect,” he says. “It’s nice to finally walk away from the work, the dialogue is between the audience and the work now. It’s the first time ever I felt I could step outside it, and that was so good.”

Diane Smyth is a freelance writer, curator and photofinder

All images © Stephen Gill

Coming up for Air: Stephen Gill, A Retrospective

Arnolfini, Bristol, 16 October 2021 – 16 January 2022

VISIT WEBSITE