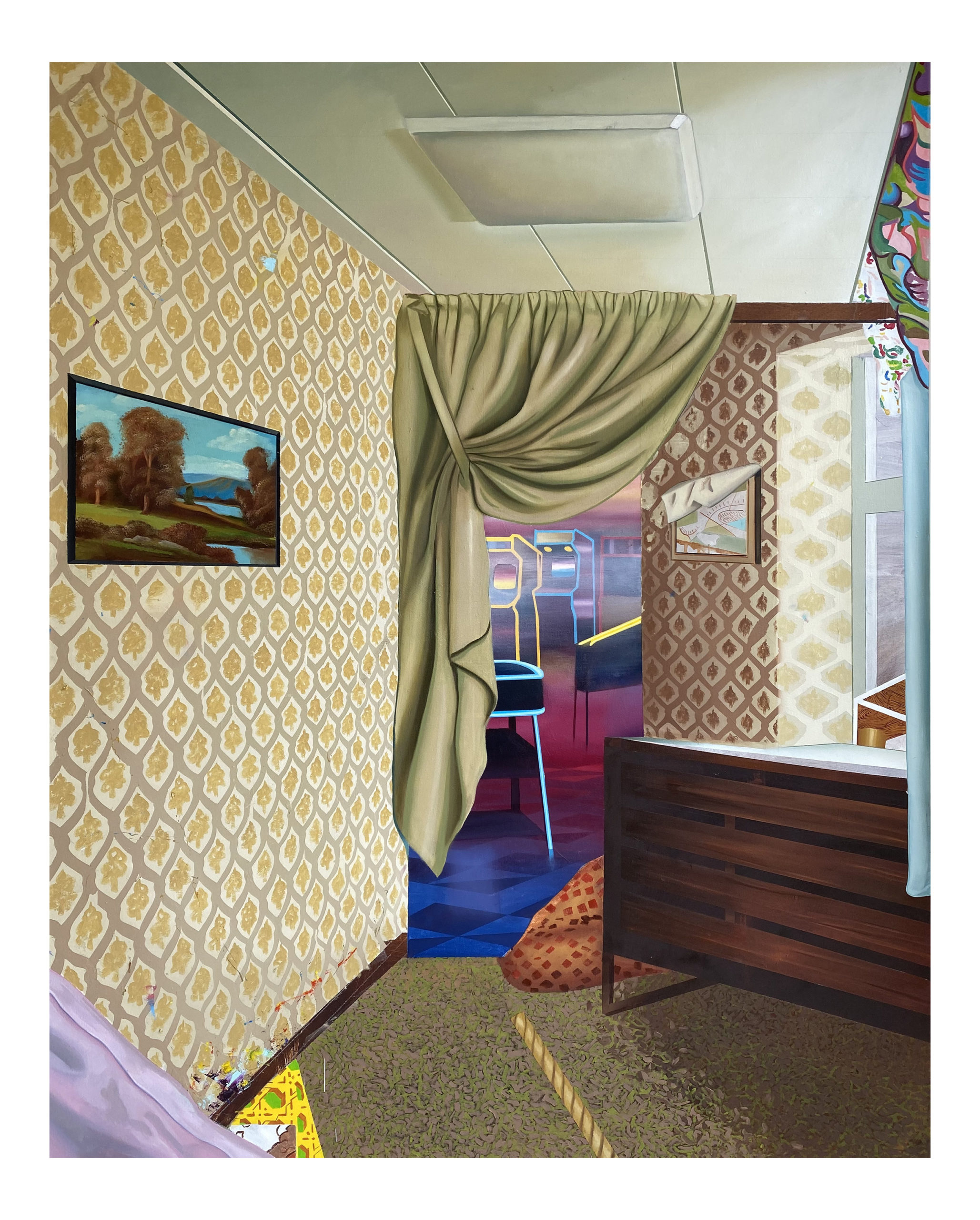

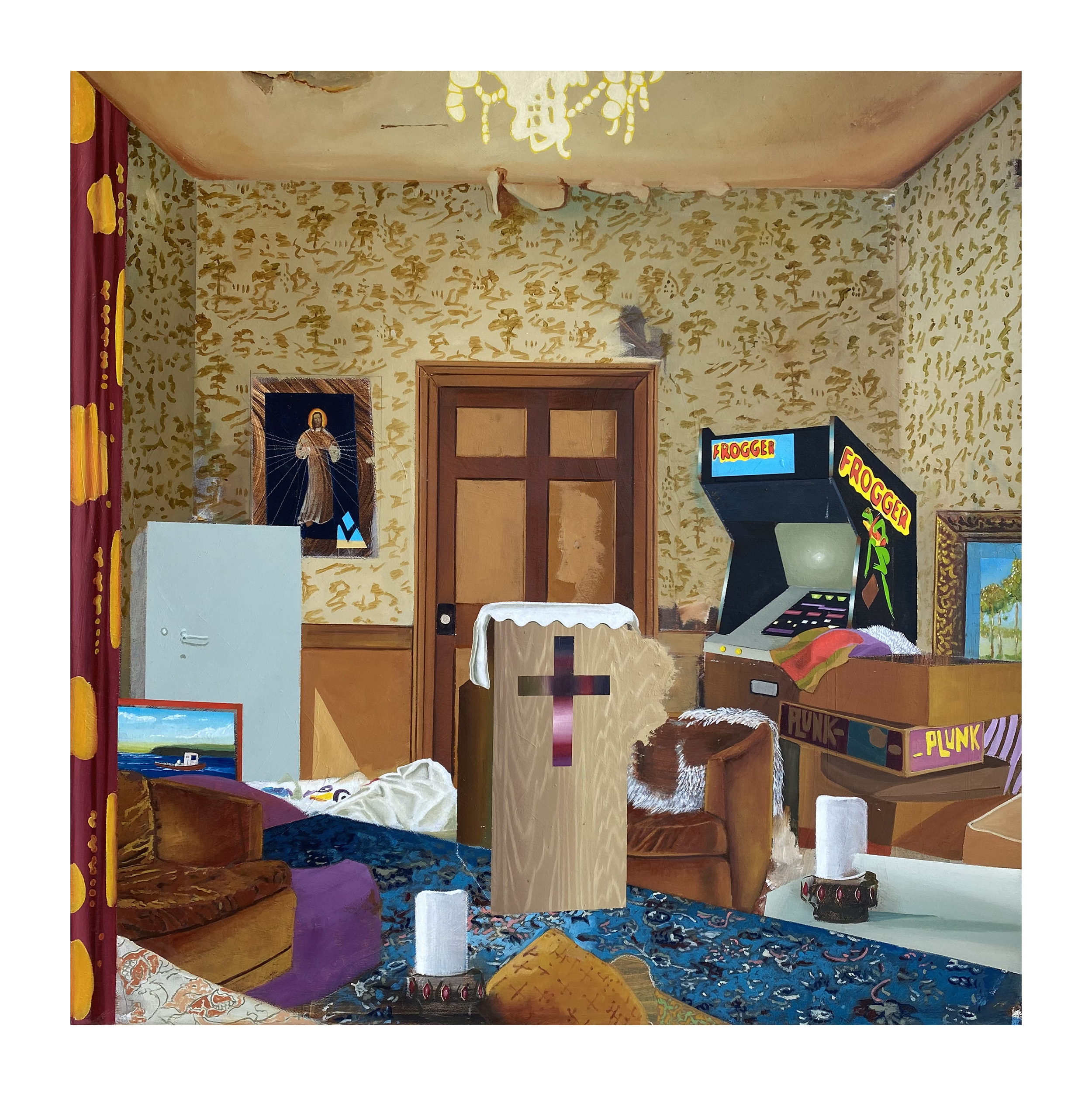

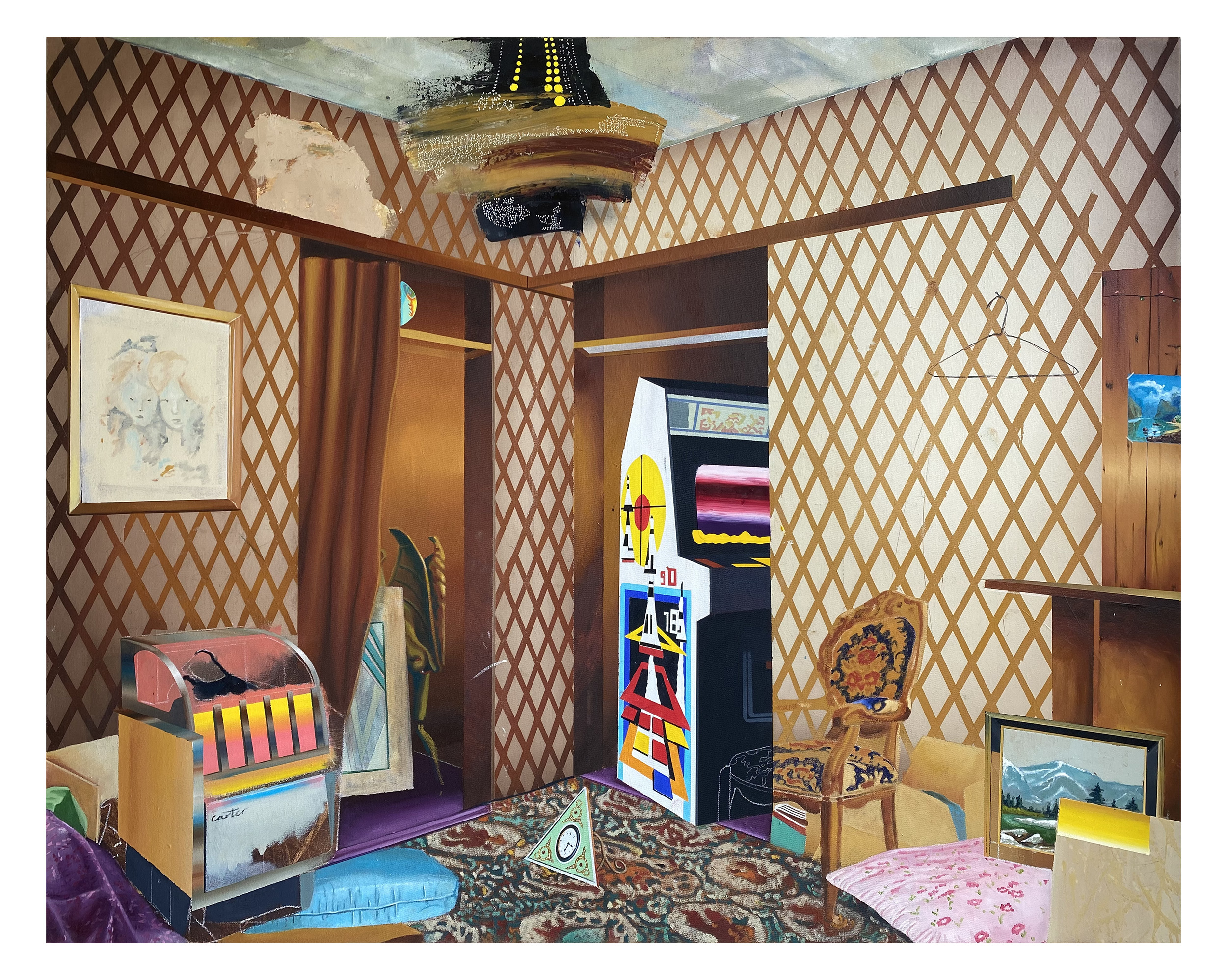

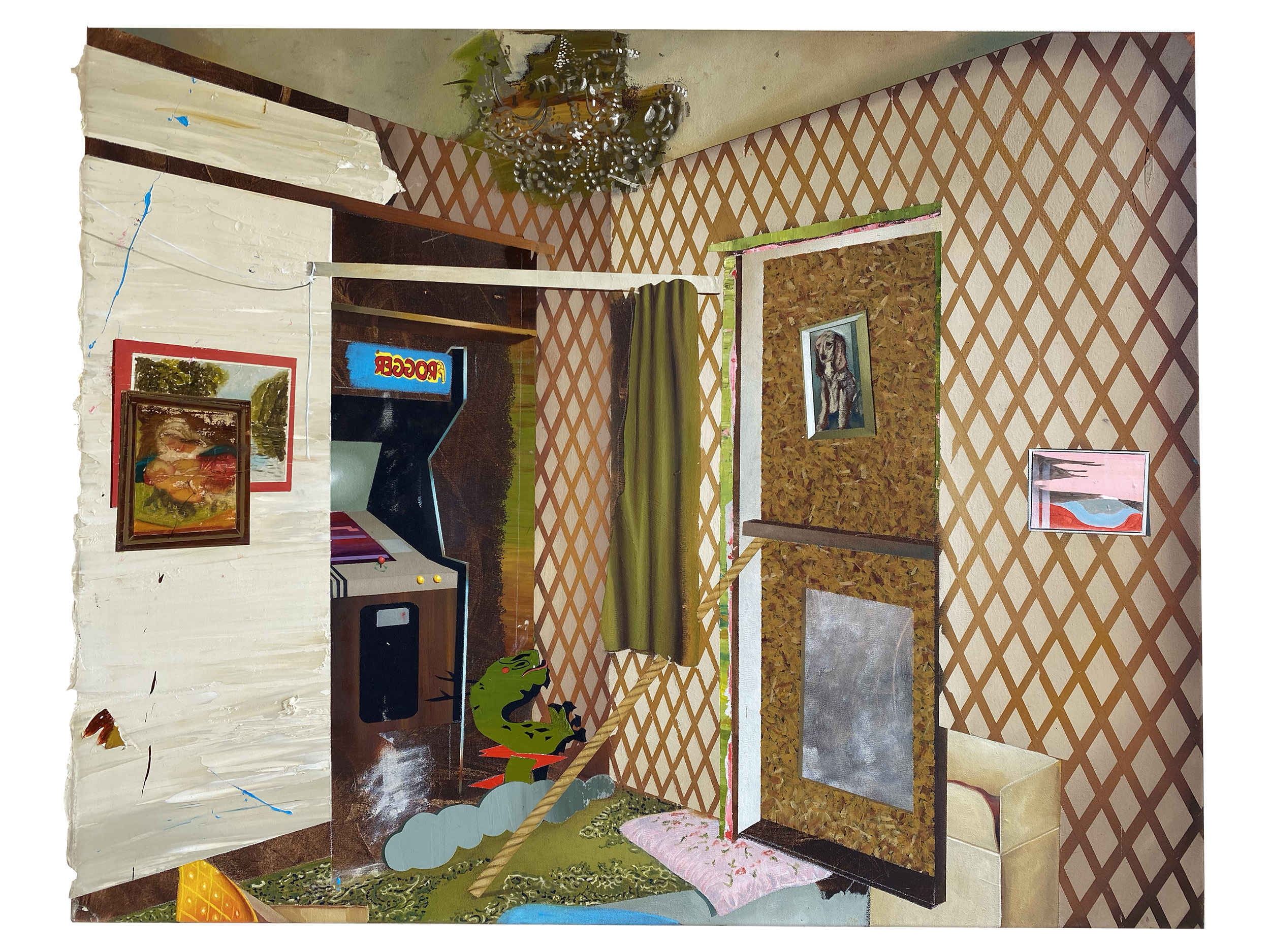

“When you first look at one of my paintings, it seems to make sense. It might look like a room, but it reveals itself in its oddity the more you look at it,” says artist Stephen Thorpe, summing up what makes his works so endlessly intriguing, and occasionally a little chilling, in their strangeness. Based in Hong Kong, where he’s a professor of painting at Savannah College of Art and Design, Thorpe graduated from his MA at the RCA in around 2015. During the course, he dismantled the concepts behind the interiors-based paintings that have been his focus for the past twelve years, and experimented with materials like bricks. Now, however, he’s firmly back to his brightly coloured, thick impasto-laden oil paint depictions of rooms or isolated corners.

Like most of his work, these recent pieces—all created since the pandemic began—show room compositions, peppered with symbols, and created from elements of the artist’s own photographs, boxes of stored magazines and images found online. Informed by his interests in sociology, psychology and his in-depth knowledge of Jungian theory, the rooms are, in basic terms, the mind: his interior spaces are our collective unconscious, populated by a mixture of familiar and half-remembered icons that veer from the dull and quotidian to those imbued with emotion and nostalgia.

What first interested you in focusing on interiors paintings?

When I was on my undergraduate, I was always interested in architectural and interior spaces. I didn’t really know why or consider a justification. Over time, the rooms kept changing slightly, and my interests changed. I started to see patterns in the world, and thought about those things and the way they manifested in the paintings. I saw relationships and connections between what I was thinking and what was happening on the canvas. They all happened in sync with each other.

The rooms feel slightly dated, there’s an 1980s and nineties vibe to them. That’s quite intentional, as I was born in the eighties, so imagery of that time is loaded with meaning and emotion for me. It would be arbitrary for me to paint something from the year 2000 and that generation, for instance, as it doesn’t resonate with me.

Why Jung? How does his work feed into this?

My brother is a sociologist, and growing up he was always feeding me sociological journals, philosophy, music, art… Now, I’m very into sociology, philosophy, folklore, religious stories, symbolism and iconography, because they all come from a very similar place and all manifest similarly across cultures. I’m referring to a Jungian term called the collective unconscious, which he believed was a series of archetypes and imagery that are inherited at birth: things like the father figure and the mother figure could be translated to a godly figure. Every religion, every culture has a god. This can also be applied to the symbology of shapes: in most cultures, circles represent rebirth, or the cycle of life, or regeneration, rejuvenation or something like that. Historically, different cultures have all these things which are variations of the same thing, and Jung believed that was a manifestation of a collective subconscious.

Myth-telling and folklore feeds into this: mythological stories and biblical stories all have a greater meaning or moral. These stories might manifest at some point in life, and can be triggered into the conscious mind. Also, with [Jungian] dream analysis, everything you see goes into your psyche either consciously or subconsciously, and these manifest at different times—often through dreams. Things that you’ve seen that you don’t consciously [think about] will come to the fore. My work attempts to visually represent elements of these things.

Then where does the image of a room, and the objects in it, come in?

The room is the manifestation of the psyche. Although I hadn’t read Jung when I was doing my undergrad, in the Jungian “dream house”, he uses rooms as a representation of the psyche, where the upper levels are the more conscious parts of the ego and as you go down, you go into the subconscious. And when I paint, I’m in a room all the time… Paint what you know!

“The act of painting is just the most beautiful thing for me”

Recently I started looking at the arcade machines, which have appeared as objects in the rooms I paint. I didn’t know why I first put one in, I think it was subconscious intuition. But then I was looking at the games: one is called Frogger, and it’s about a frog trying to cross the road and the constant anxiety of trying not to die; and one is Pacman, where you’re just trying to eat things before they eat you. So that’s pretty self-evident, right? That’s like life; you’re just trying not to die.

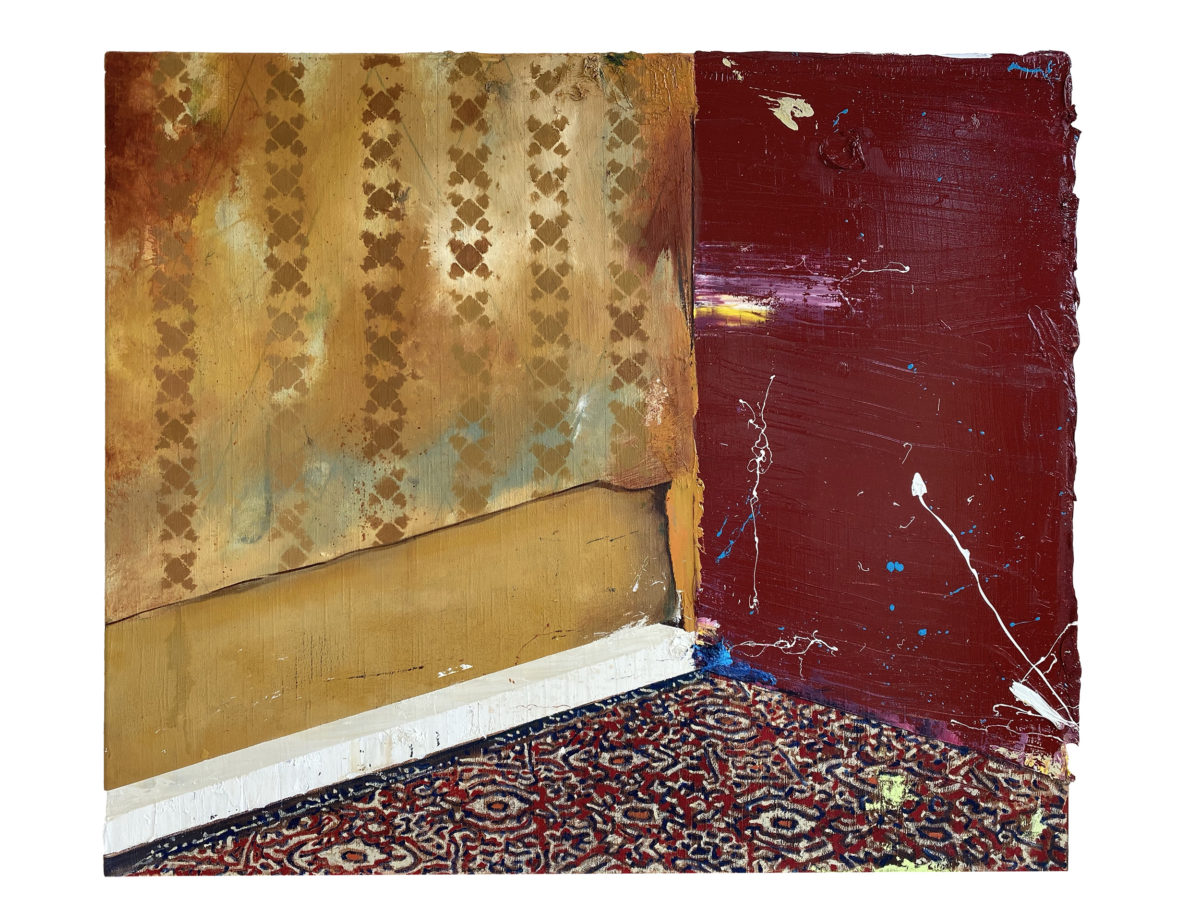

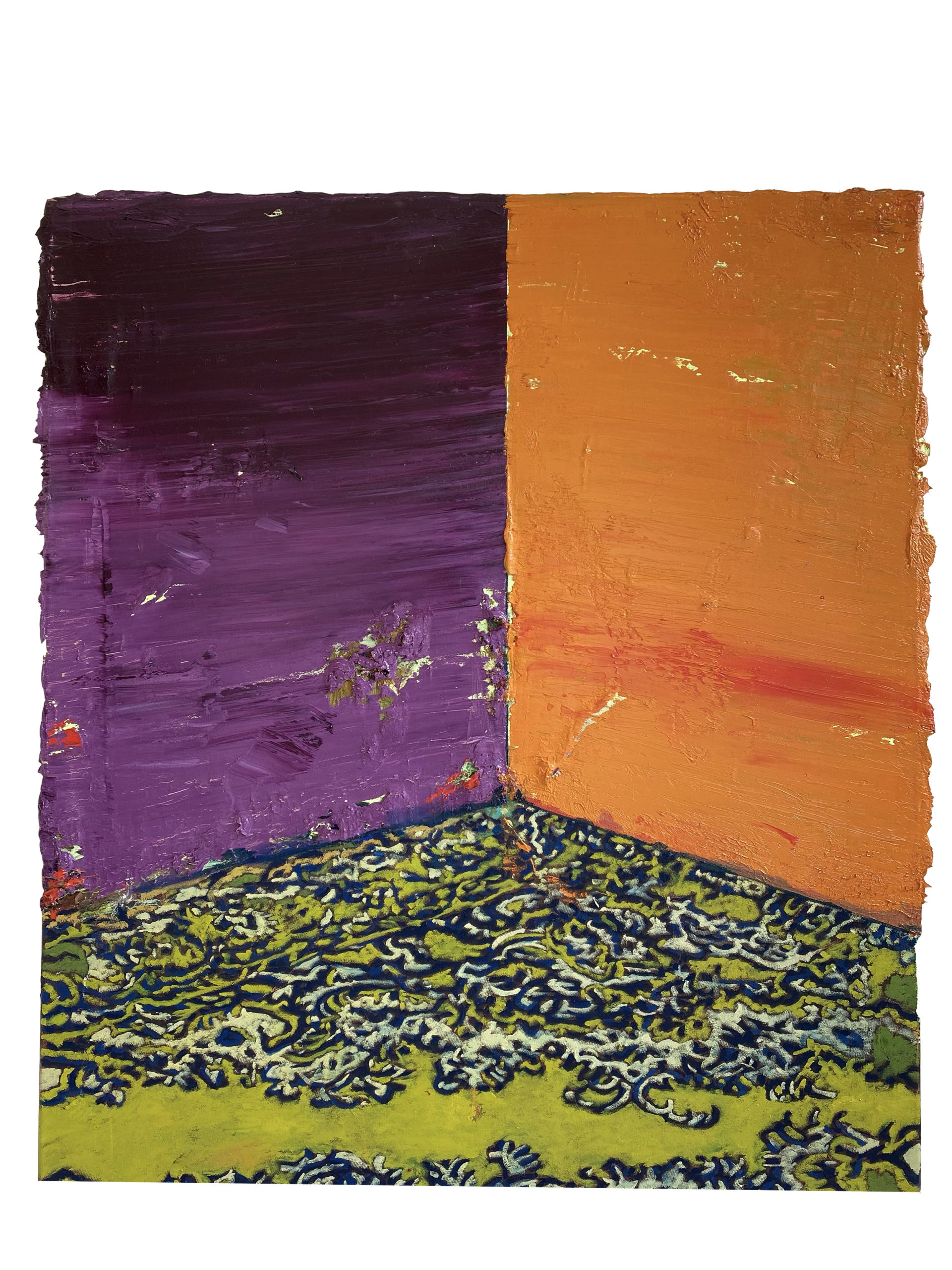

Tell me more about your paintings that hone in on corners.

The corners are very significant. A French philosopher, Gaston Bachelard, wrote a book called The Poetics of Space (1958), which is a phenomenological inquiry into architecture. He talks about corners and how they can be a place of sanctuary and rest, or a place of anxiety and feeling trapped: literally backed into a corner.

A corner also has this quality of an interior and an exterior. In my work I think about a constant interplay between the conscious and the unconscious. With the corners, the interior would be your subconscious and the exterior would be your ego, the conscious part. In these paintings the paint is really thickly applied, so it’s kind of like you’re going into the recesses, the dark parts.

- Left: The Germ of a Room, 2020; Right: A Real Cosmos in Every Sense of the Word, 2020

Why is painting the best way for you to express these ideas and concepts?

I think I always had a propensity to paint, and the act of painting is just the most beautiful thing for me. There’s all the conceptual stuff, which helps you inform the work, but there’s also the joy of just moving paint around a canvas: I absolutely love looking at paintings—the texture and the quality of paint—and even more so when you start to handle it yourself. In some of the works, like the corner pieces, the paint is very thickly applied and it becomes really tactile and unctuous. Paint just seems like such a good medium to use because it can be sculptural. And you can really play with representing three dimensional things. So you can make perspective become slightly “off”, and things can look out of place so you can represent things in a way that’s reminiscent of a dream.

In the handling of the paint there’s a duality between the really liberal, gestural mark making and the really tight elements of design and patternation like the edges of the arcade machines for instance, which are hard and sharp. The painting part itself is really important as well as the conceptual elements, it’s constantly balancing these two things in the work.