Forty years ago this September, a group of nearly 40 women walked more than 100 miles from Cardiff, Wales, to Greenham Common air base in Berkshire, England. The journey took a week, and when they arrived some of the women chained themselves to the fence surrounding the air base. They were there to protest America’s installation of 96 Tomahawk nuclear cruise missiles. The Greenham Common protestors were part of a loosely organised peace group called Women for Life on Earth. The proposed placement of these American missiles on British soil, each of which possessed a destructive capacity four times that of the bomb that destroyed Hiroshima, was met with fury and despair.

Some of the women left Greenham and returned to their lives, but others refused to leave. They set up camp and endured mud, rain, bulldozers and arrests in order to stay put. The following spring, in 1982, the group voted to make the protest women-only and Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp was born. The women of Greenham anchored the movement in their particular brand of 1980s feminism: second wave, centred on domestic motherhood but influenced by lesbian separatism, and reliant on women’s creativity as the means of protest. They saw war as patriarchy and the nuclear bomb as a physical manifestation of male ego and capacity for destruction.

In December of 1982, the camp’s numbers would temporarily swell to more than 30,000 as women from across the country joined to surround the nine-mile perimeter of Greenham Common in an event known as ‘Embrace the Base’. They linked hands and decorated the wire fencing with meaningful objects and mementoes including toys, photos, children’s clothes and wool. The unusual form of protest gained national attention. The women continued to make headlines by blockading entrances to the base, cutting through fences, and on one memorable New Year’s Eve, dancing on the silos intended to house the missiles. The camp finally disbanded in 2000.

Minneapolis-born artist Ellen Lesperance first discovered the Peace Camp in 2005, when she was a part of an all-woman commune in New Mexico. There she met one of the original protestors. “She told me stories about the camp,” she says. Lesperance’s work, which draws frequently on feminist activism and the history of direct creative action, has been deeply shaped by those stories. For the past decade she has researched dozens of Greenham Common archives, trawling through footage and reading accounts from the women who doggedly campaigned for nuclear disarmament.

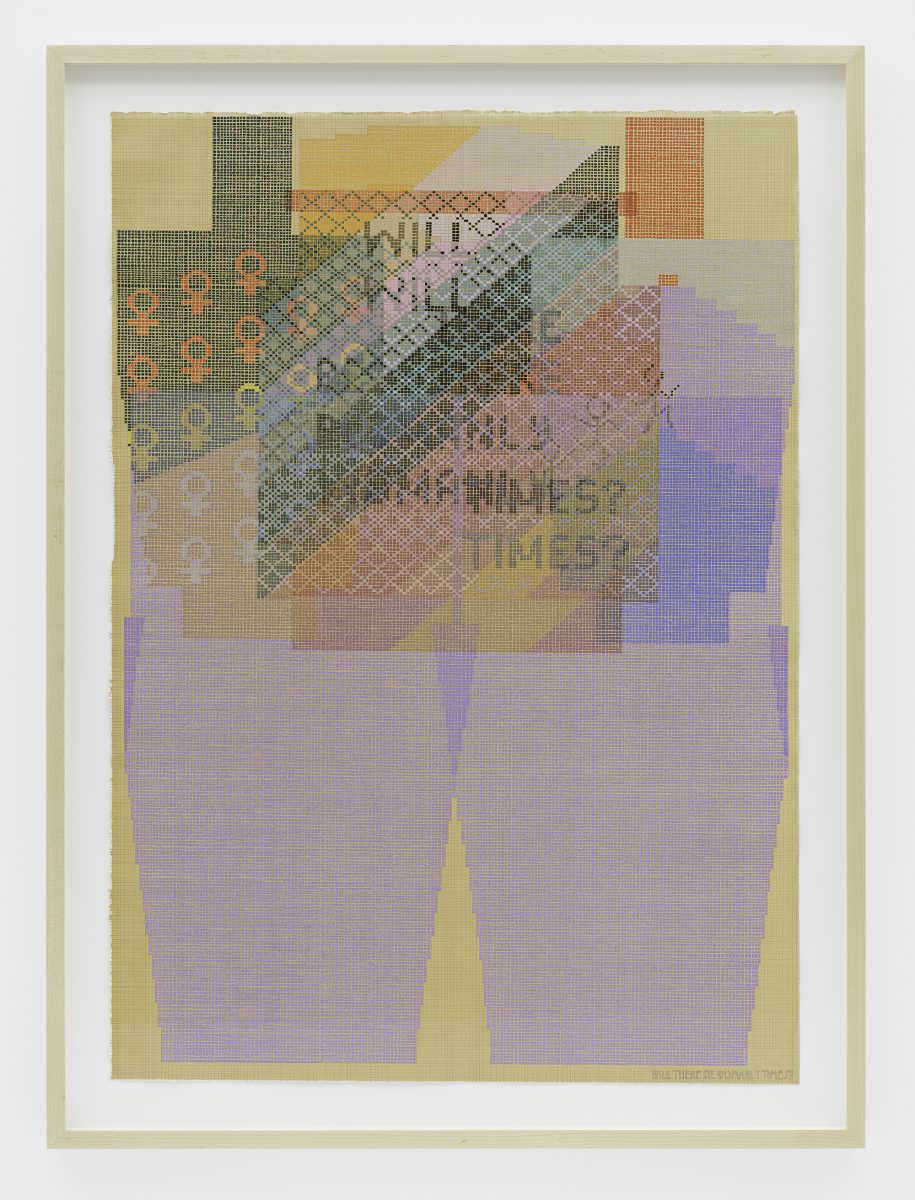

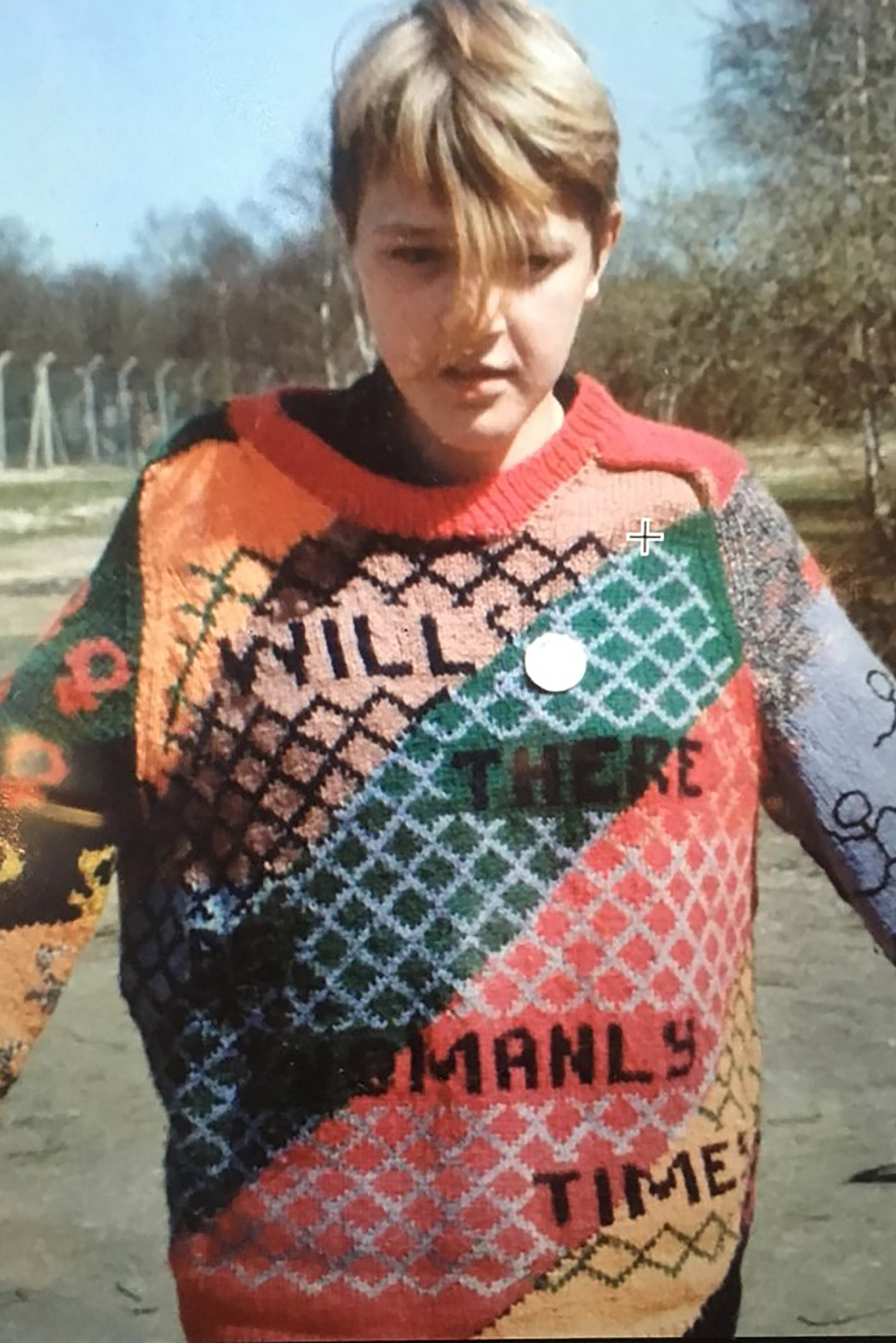

Lesperance’s first solo show in London, Will There be Womanly Times? at Hollybush Gardens, brings together the fruits of her research. Lesperance approaches the lives and protest methods of those who made their home at Greenham Common through a single focal point: their knitwear. Many of the women in the camp wore distinctive handmade jumpers, and incorporated symbols and slogans into their clothes that spoke to their aims. “I think they were interested in utilising whatever materials and skills that they had immediately at-hand to argue for themselves,” Lesperance observes. “Clothing, when reproduced in the media as still or moving images, can easily carry communicative protest messaging.”

“The paintings can be followed as instructions for knitters… to bring the garments back into the present or a future world”

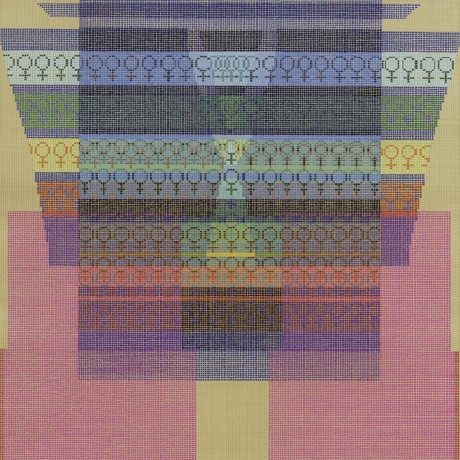

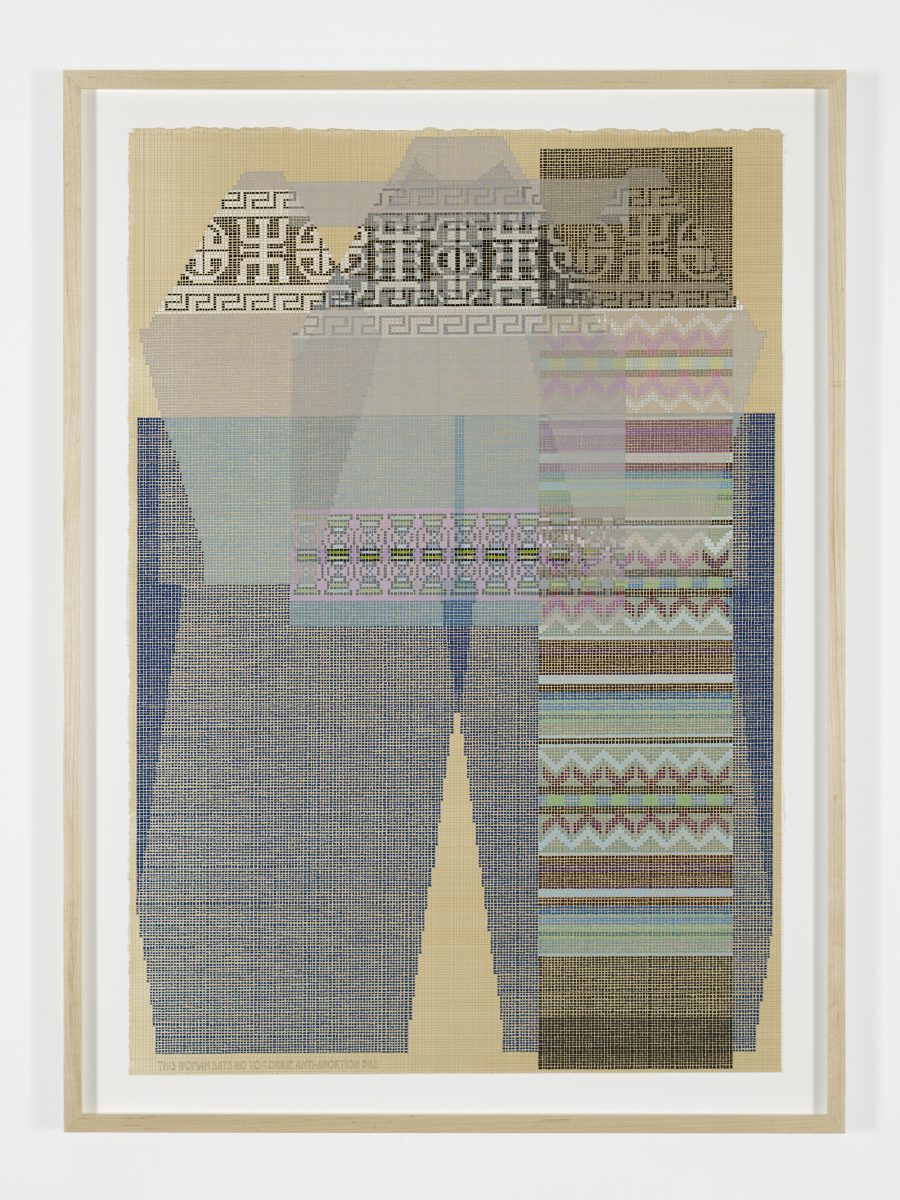

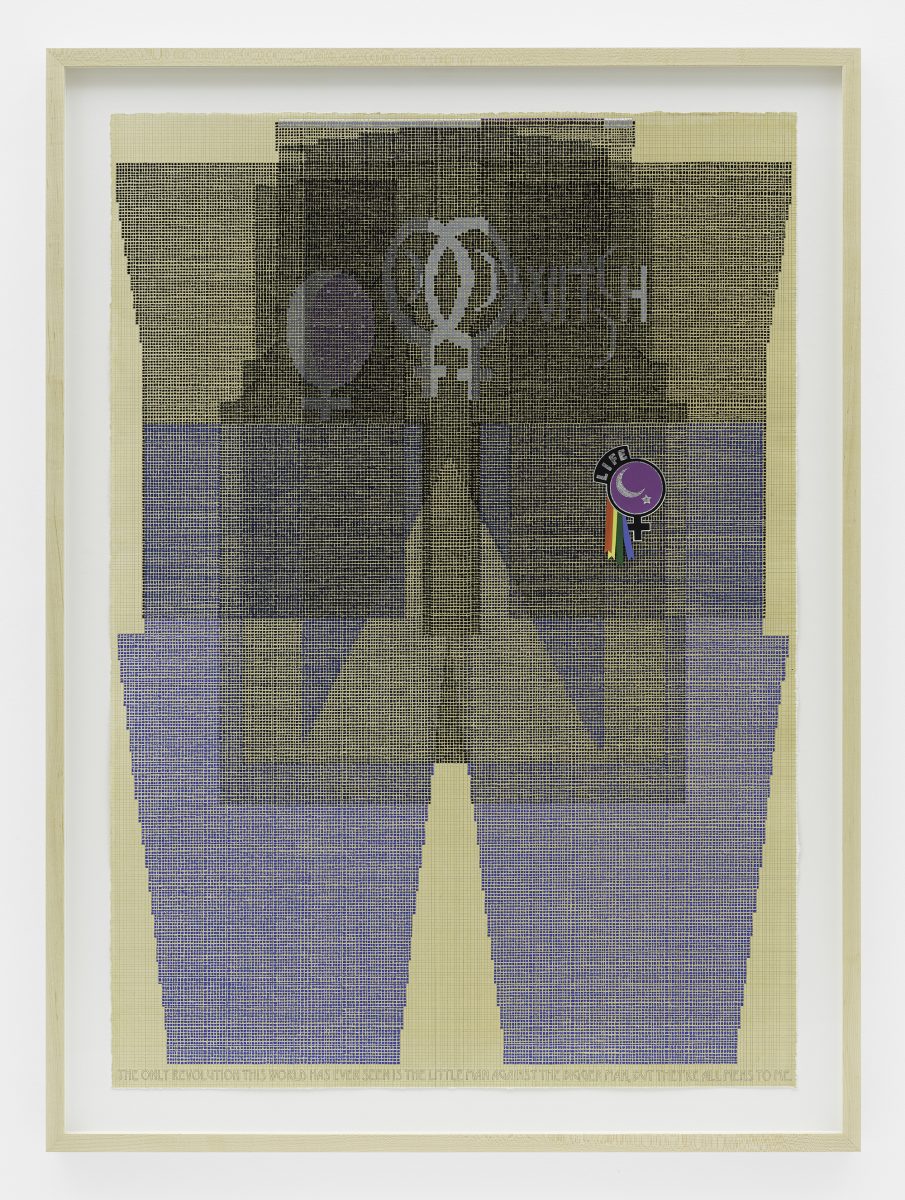

In Lesperance’s hands, these jumpers have been transformed into a series of colourful paintings and hand-knitted recreations. Her gouache paintings draw on Symbolcraft, which is a simple and popular system of visual notation used to provide knitting instructions. Working exclusively from archive images and footage (Lesperance is yet to find a single garment from Greenham still in existence), the jumpers worn by protestors have been broken down into a series of pattern pieces.

On her densely gridded paintings, each individual grid represents a single stitch. For anyone well-versed in Symbolcraft, these paintings are not just images of garments, but practical guides for the viewer. “My interest in patterning these jumpers that no longer exist as objects in the world is celebrational,” Lesperance says. “But it also is generative in a literal sense because the paintings can be followed as instructions for knitters… to bring the garments back into the present or a future world.”

“What a person chooses to wear communicates identity, and in a way that is potentially far more profound in its self-selected nature”

Although some of these jumpers are of the sort one might expect at an outdoor protest with damp cold nights and the smell of woodsmoke (striped, colourful, or featuring traditional patterning like Fair Isle) many contain what Lesperance calls a “unique vocabulary of ideological symbols.” These knits were powerful tools of communication. They spoke to second-wave feminism (the women’s symbol), lesbian identity (the labrys, the pink triangle, and the nascent use of the now-ubiquitous Pride rainbow), the anti-nuclear movement (doves and smiling suns), and Greenham-specific symbols (the spiderweb and the snake). Several featured slogans. The title of the show is taken from one elaborate jumper made from diagonal stripes of green, yellow and red, the black text across the chest reading “WILL THERE BE WOMANLY TIMES”.

Nowadays we are used to seeing jumpers proclaim the beliefs of the wearer. So much so that feminist sloganeering in the form of clothing has, in recent years, earned a bad rap. Such garments are seen to embody the worst hypocrisies of capitalist exploitation, whether it’s Dior’s £580 ‘We Should All Be Feminists’ T-shirt or a top proclaiming ‘Girl Power’ produced in a Bangladesh factory where workers make only 42p an hour. More subtly, these pieces may provoke embarrassment in their associations: the #girlboss-style sentiment, the whiff of transphobia that sometimes accompanies the use of the female or Venus symbol.

“These jumpers have been transformed into a series of colourful paintings and hand-knitted recreations”

It’s helpful to unpeel present context and return to the roots of these types of garments and symbols. Lesperance’s exhibition invites us to think about the tactility and work that went into the jumpers worn at Greenham Common: the act of their making; the way they kept the wearer warm in inhospitable conditions; their dual function as practical layer and articulate symbol of solidarity. They offer another form of intimacy. “I think of my paintings as an alternate to portraiture: a reproduction of what a person’s body and/or features may look like,” Lesperance says. “What a person chooses to wear on their body surely communicates identity, and in a way that is potentially far more profound in its self-selected nature.”

There are many ways of retelling history. We have facts and dates, first-hand accounts and newspaper headlines. But Lesperance’s choice to revive this 19-year-long campaign through its clothing is moving. Interest in fashion has long been viewed as a female pursuit, while knitting is still largely seen as a domestic craft. Accessing the past through these more marginal or material avenues is not a new phenomenon, but here it is unusually apt. These jumpers speak to the tenacity and ideology of their wearers. They become a fitting emblem of their style of campaigning.

The women at Greenham saw protest as personal and imaginative. They sang songs and dressed up as witches and teddy bears. They wove intricate structures from wool in the holes they made in the air base’s fences, working like spiders to draw attention to the damage even as they repaired it. As Lesperance observes, “knitting is a practice that relies on the steady and repetitious building of one small stitch upon another to build a stable form.” Knitting speaks to reliance on others. It demands being part of a whole. These jumpers were made, worn, passed on, and perhaps lost or unravelled again years ago. But here they are woven into something wider.

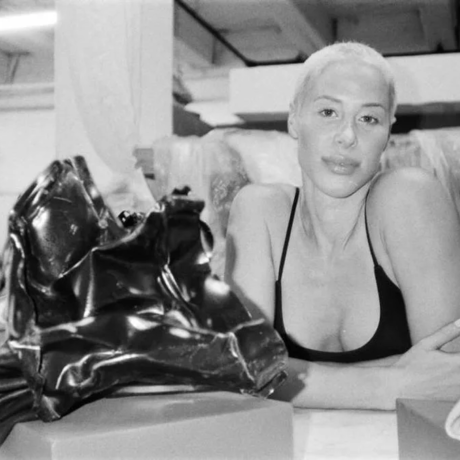

Rosalind Jana is a writer on fashion, art and culture. She is a contributing writer at Vogue Global Network and a columnist on photography and style for Magnum Photos

All images courtesy Hollybush Gardens

Ellen Lesperance: Will There Be Womanly Times?

Hollybush Gardens, London, until 31 July

VISIT WEBSITE