Margate made the news last week when a cargo ship almost collided with its Antony Gormley. This is something Tracey Emin is excited about, she says to a room full of press at Turner Contemporary. Not the destruction of a public sculpture, but how the media stir it caused might benefit her hometown. She will be moving back, following her most famous work, which is now showing at Turner Contemporary, surrounded by Turners.

Margate made the news last week when a cargo ship almost collided with its Antony Gormley. This is something Tracey Emin is excited about, she says to a room full of press at Turner Contemporary. Not the destruction of a public sculpture, but how the media stir it caused might benefit her hometown. She will be moving back, following her most famous work, which is now showing at Turner Contemporary, surrounded by Turners.

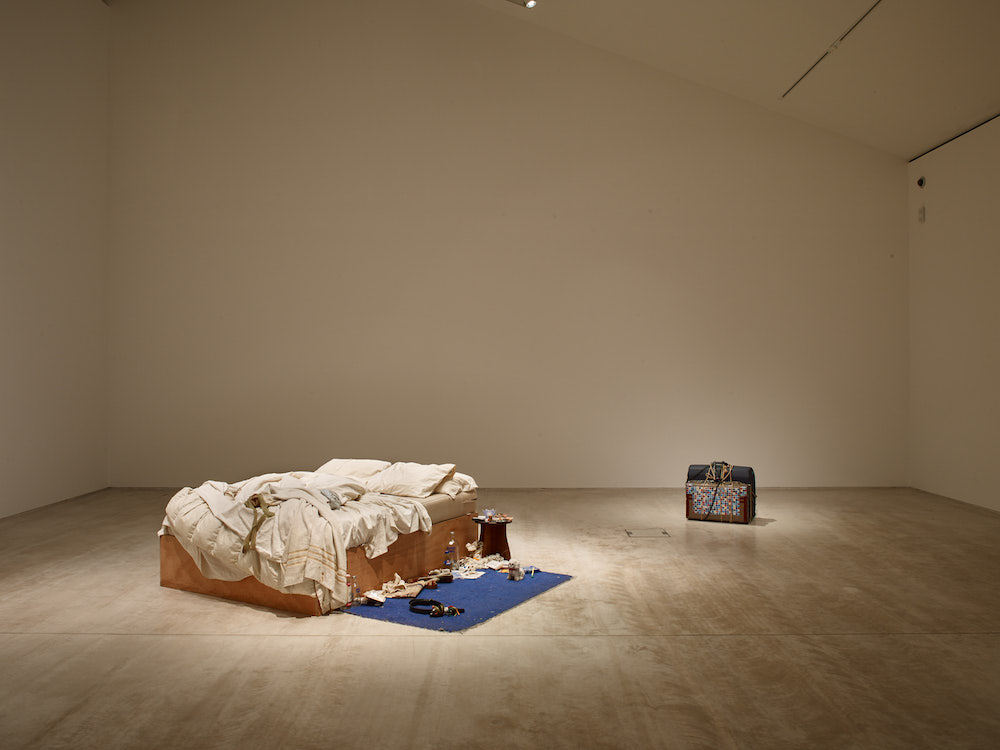

The last time British art caused a proper stir was during the late nineties, when Emin made her now-infamous television appearance, when she swore like a trooper, called Will Self a fake and stormed off. This was the era of My Bed, the work that captured the aftermath of a messy break-up, and other formative experiences that took place in the bed from which she hadn’t been able to move for days. My Bed’s garnish of sanitary towels, used condoms and dubious stains—the stuff of life—created a controversy that became part of the work. “It really was a seminal work,” I overheard someone say at the press day while looking at that condom—brown now, all but a rusty stain on the carpet.

© Tate, London 2017

Made in 1998, My Bed is nearly twenty years old. It preserves, even as its components decay, Emin’s sensibility as it was in that moment, a portrait of a different person. “As I get older,” she says, “all the objects and the bed get further away from me and how I am now. You know, I don’t smoke, I don’t have sex, I don’t use contraceptives, I don’t have periods. I don’t wear small pale blue knickers that look like one of Turner’s clouds. I don’t make stains on the bed like I used to and if I did I wouldn’t have a bed like that. The sheets would get washed immediately.”

Asked what she thought it was that made people react so strongly to her bed, she says: “I think people hated it because they hated contemporary art, or they hated new ideas, or they hated to be exposed. Basically, I’m just exposing their lives. Everybody has a stain in their life to some degree. I’m just saying it’s okay. Imagine fucking all the time, making love, and never making a stain? You’ve got a big problem.”

In the gallery, she remarks at how much light shines onto the bed. Even without the spotlight, the work feels like it deserves a spotlight, or rather, it generates its own: the static of defiance, vulnerability and pungency it gives off. Emin stands near it, posing for photographs. She is sleekly stern, matter of fact: practiced at playing her hits. But when posing by a Turner—thirteen of which she has chosen from Tate’s permanent collection and hung around the room—she is invigorated, hopping from trainer to trainer, joking with the photographers.

“We all know Turner was a really raunchy man. He was full of fecundity and action.”

One (Seascape, c.1835–40) matches her bed, colour for colour. “If you didn’t know you’d think I made the bed as a project: here’s a Turner, now make a bed out of it. It’s uncanny. The pair of blue knickers, the sandbanks with the sea…” Indeed, even tights thrown on the bed match a green fluorite colour that the late artist found and brought out in his skies and seas like no other. Emin’s work, in turn, emphasizes that the Turners, for all their beauty, are grotty, too. The artist liked to get literally hands-on with his canvases, kneading and gouging the paint.

“We all know Turner was a really raunchy man,” she says. “He was full of fecundity and action. And I am, or I used to be.” She smiles and looks at the floor. “His masculinity is incredibly feminine as well: the way he approaches his painting; his temperament and his emotions were open which was quite rare at that time. So I’m pleased the bed is vulnerable and open, and so are Turner’s paintings.” Another oil is dark and angry (Stormy Sea with a Blazing Wreck c.1835–1840). This could have been the subtitle for My Bed.

Every time Emin sets it up in a new space, the work takes on a new energy depending on how she feels. Sometimes it is a peaceful and calming ritual. Sometimes she has mussed it up, or undressed and rolled around in it. This time she was in a bad mood. It’s the “raunchiest” she has ever made it, she says. “That’s because it’s in Margate.”

“I’m really wondering when I come back whether all the good memories will come through. It will be coming full circle.”

Margate is where it all happened: it’s where she grew up, went out dancing, got heckled. It was here she got some of her front teeth knocked out, which resulted in that resourceful, tough but mischievous half-smile with which she has come to be associated. It was here she was raped at the age of thirteen. “Lots of people have asked me if I think my work will change [moving back]. And I think it will. I worked for years with my childhood, using my childhood and bad memories. And I’m really wondering when I come back whether all the good memories will come through. It will be coming full circle.”

London, she says, is “completely crushing” her. She had plans to extend her studio which the Tower Hamlets council wouldn’t let her actualize. In previous years she talked about building an archive there that would be open to the public after her death. I ask if the plan has moved home, too. “My archive will be in London but my museum will be in Margate. No, when I die hopefully there will be a museum here. Which I think will be brilliant for Margate: you know, Margate girl makes good. I hope people will come.” Later, to crowds at the evening opening, she suggests that Margate could become, “not the epicentre, but the great edge” of British culture. “My Bed’s here for three months. But it’s not my Margate bed. It is the bed I made when I was away from you.”

Earlier, she told an anecdote in which Charles Saatchi, having bought the work, asked her to promise never to make another one. “I said, how could I ever promise that? That’s technically impossible. I’m gonna make my bed every day from now on and I have.” Saatchi no longer owns the work. So even if Emin was the type to be bound by a dealer’s whims, she’d be out of the bind now. Would you ever make another bed, I asked her. Showing who you are now, who you have become, without the stains? “No it would be so boring,” she laughs. “Could you imagine it? ‘My bed is immaculate, with its really nice Ralph Lauren tartan pillow cases and everything.’ I’m a different person now. Of course, I’m still partly the same but lots of me has changed. Including my bed, and my sleeping partners, and my sleeping habits, and what I take to bed with me.”

Tracey Emin, ‘My Bed’/JMW Turner

Until 14 January 2018 at Turner Contemporary, Margate

turnercontemporary.org

All images (unless otherwise stated):

Installation view

Photo: Stephen White

Courtesy Turner Contemporary