Nudism is not a subject generally associated with the British, a nation who traditionally remove as little as possible when enjoying the country’s tiny glimmers of summer sunshine. As a Brit myself I have often felt that the perennially gloomy climate is surely linked to our perceived prudishness when it comes to baring all.

It’s so much more tempting to cast off your clothes on the shores of the French Riviera than the chilly pebbled beaches of the British seaside. And yet in the 1920s nudism (inspired in part by the blossoming movements in Germany and France) made its way across the channel, leading to the creation of the British Naturism organisation.

The blossoming of naturism as a social pursuit in the UK, and its subsequent evolution over a 50-year time span, is the subject of a new book by cultural historian Annebella Pollen

, titled Nudism in a Cold Climate. Pollen pays particular attention to the movement’s visual identity over this period, as documented in the books and magazines of the time, which inevitably relates to shifting social and political views surrounding the naked body.

“Nudism arrived in Britain after the First World War,” Pollen says. “I was surprised to learn that in 1920s and 1930s Britain, going nude socially in groups was an elite, rather intellectual practice. It was referred to as gymnosophy, a conjugation of the Greek words for body and wisdom.”

In the book, Pollen describes the movement’s earliest pioneers as “modernist artists and authors, sex reformers and spiritual seekers, experimental educationalists, physicians, and psychologists”. They fervently believed that exposing one’s entire body to the sun promoted better health, and offered the ultimate freedom from repression.

“While nudism was never an art movement as such, it drew on a lot of the artistic discourses at the time”

“One of the movement’s biggest impulses was the tuberculosis epidemic in Europe,” explains Philip Carr-Gomm, the author of A Brief History of Nakedness (2010). “At the turn of the century, people like Dr Auguste Rolliet in Switzerland began exposing tuberculosis patients to the sun, and found that sunbathing naked, and breathing in fresh air, actually helped them to get better. This idea soon took hold across the continent, and at one point they even had schools that taught children in the nude, impossible to imagine now!”

But while some bold practitioners readily embraced the idea that nakedness could be enacted for health reasons alone, removed from any sexual connotations, many were scandalised by it. “There were some very closed-minded attitudes to the naked body in Britain a hundred years ago,” Pollen expands. “To some, taking your clothes off in group situations was nothing short of evil.”

As such, the first photographs of British nudists were self-consciously health-oriented in an effort to legitimise their ideology. Many were captivatingly artful. Some show toned nude models in static, sporting postures reminiscent of classical statuary, flexing muscles or reaching for the sun. In others, they adopt expressionist dance positions.

“Many of the images are very painterly in composition,” Pollen reflects. “Models were often arranged picturesquely, with one foot in a pool of water, for instance, in the style of famous paintings of the period, or in a Venus-style pose from classical art history. So while nudism was never an art movement as such, it drew on a lot of the artistic discourses at the time.”

“They wanted to show what nudism could achieve,” says Pollen. “If you were fit and healthy, and you practiced nudism, you’d become like one of these gorgeous creatures. But many of nudism’s actual members were middle-aged and ‘imperfect’ of body by the then-traditional standards. This is one of the movement’s biggest contradictions.”

“They fervently believed that exposing one’s body to the sun promoted health, and offered the ultimate freedom from repression”

The waters grew murkier still when, in the midst of the Second World War, pin-up culture took hold, spawning cheaply printed publications filled with images of scantily clad, Betty Grable-style beauties. In theory, the British naturists viewed such pictures as a “demeaning sexualisation of the naked body,” Pollen says, but their publications tell a different story.

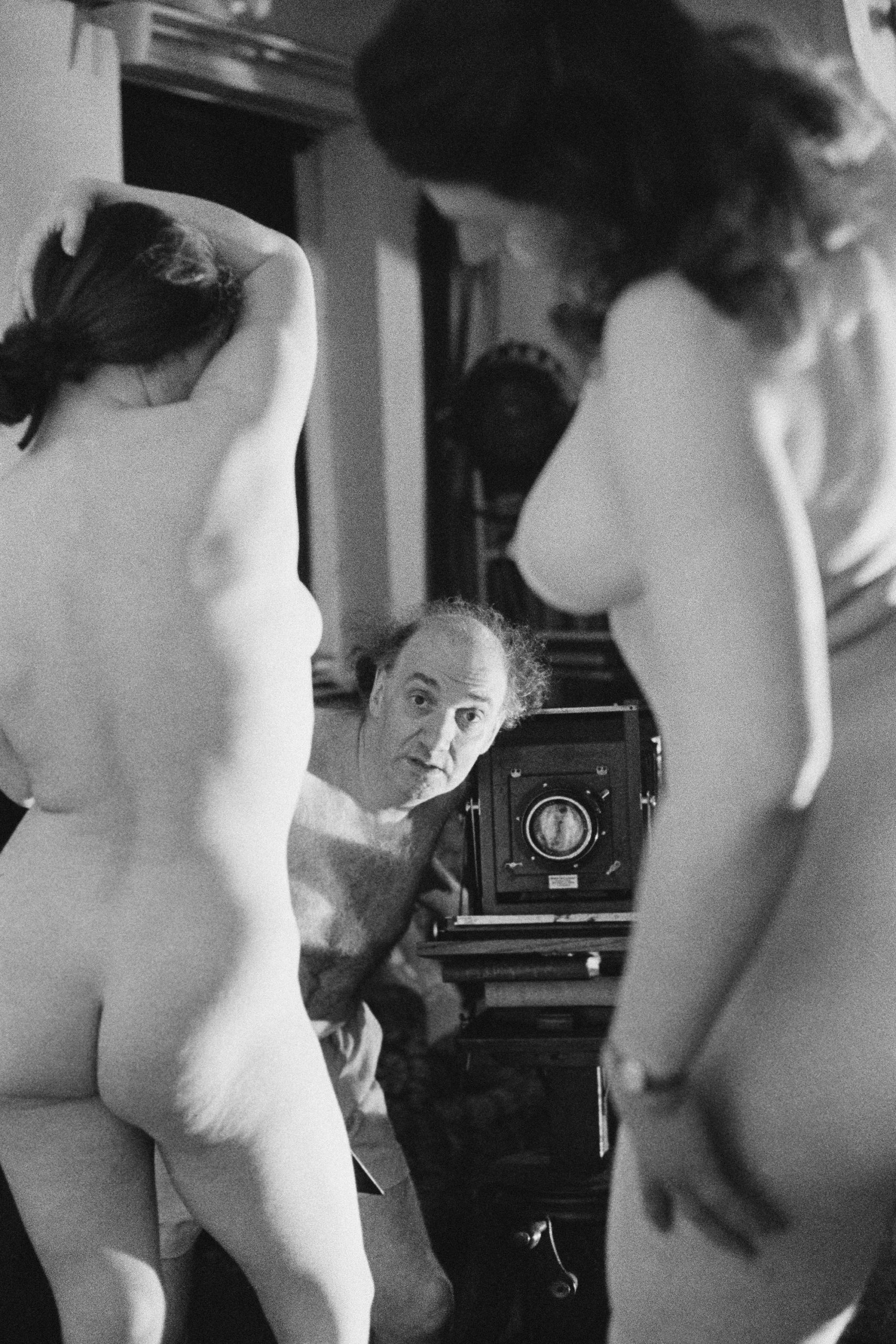

“The pin-up and naturist pictures don’t look that different, except in pose and setting,” she notes. “Sometimes you’ll find the same photographers shooting the same models for both.” The glamour model Pamela Green, for instance, the life and business partner of photographer George Harrison Marks, can be found standing naked and beatific in a field promoting the concept of a wholesome nudist utopia one moment, and lounging in stockings and suspenders the next.

“To depict the naked body under any other guise than nudism was morally suspect,” Pollen explains of the crossover. “Obscenity laws in midcentury Britain were really strict so the conditions in which nude photos could be bought and sold were really narrow, and even then pubic hair had to be blurred out.”

Under the guise of purchasing a magazine about the scientific benefits of nakedness, buyers could access images of nude bodies at newsagents and stations as opposed to under the counter. Although British naturism remained a minority movement in the 1940s and 1950, its publications sold in their thousands.

“Nudism arrived in Britain after the First World War. Going nude socially in groups was an elite, rather intellectual practice”

Nevertheless, there were some naturist photographers who earnestly sought to argue for the liberation of the nude image. One such figure was Jean Straker, who ran a photographic club in Soho in the 1950s and 1960s, providing technical and philosophical instructions to amateurs on how to take artistic photographs of the nude. “He produced books of nudes which he saw as self-consciously artistic,” says Pollen. “They were formally experimental, often in these semi-surreal settings with dramatic shadows and curious props in the frame. That’s the closest to the avant-garde artistic movements that naturist imagery ever really gets.”

“Although British naturism remained a minority movement in the 1940s and 1950s, its publications sold in their thousands”

“The 1960s saw a movement towards flower power liberation, where younger people used nakedness as a way to express their freedom from social convention and taboos,” Carr-Gomm explains. “So the idea of naturism started to become rather quaint, because from that point of view you were still buying into rules and regulations as you only took your clothes off in designated settings.”

Indeed, by the 1970s, the nude body had become so normalised that tabloid newspaper The Sun began printing daily images of naked women on its infamous Page 3. “That’s why I decided to end the book in the early 70s,” Pollen explains, “when we entered a whole new world of feminist art criticism and feminist art practice.”

Cultural curiosity aside, perhaps what is most interesting about the visual history of the modern British nudist movement is that it embodies all of the contradictions that have long surrounded the depiction of nakedness. Whatever your intention for showing the nude body, it can and will be taken out of context.

These naturists, despite their attempts to the contrary, never managed to avoid the overt idealisation of the nude body. As such, many a naturist publication lingers on in dusty attic boxes, the relics of grandparents who never once shed their clothes beneath the cool British sun.

Daisy Woodward is a Berlin-based writer and contributing editor at anothermag.com

All images courtesy Atelier Éditions