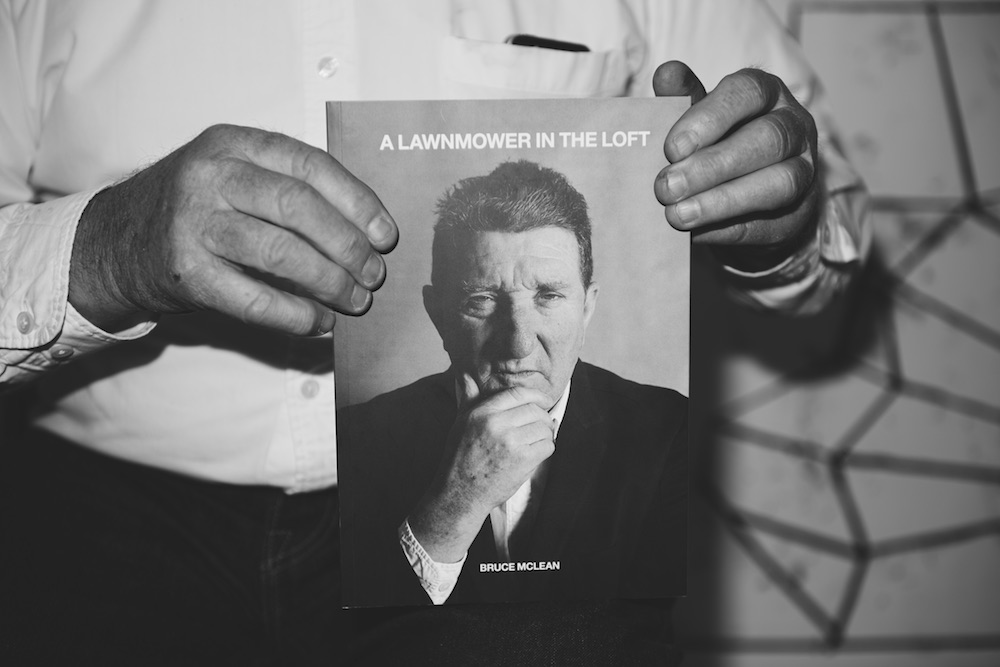

Born in Glasgow in 1944, McLean studied at Glasgow School of Art and left in 1963 to enrol at Central Saint Martins in London. At the forefront of British conceptual art in the 1960s and 70s, McLean made his name with works including Pose Work for Plinths (1971) and one-day “retrospective” King for a Day at Tate in 1972. In his recently published autobiography, A Lawnmower in the Loft, he relays anecdotes from his life and career with his trademark humour and wit. I met McLean in his West London studio, which he has had for eight years.

Born in Glasgow in 1944, McLean studied at Glasgow School of Art and left in 1963 to enrol at Central Saint Martins in London. At the forefront of British conceptual art in the 1960s and 70s, McLean made his name with works including Pose Work for Plinths (1971) and one-day “retrospective” King for a Day at Tate in 1972. In his recently published autobiography, A Lawnmower in the Loft, he relays anecdotes from his life and career with his trademark humour and wit. I met McLean in his West London studio, which he has had for eight years.

Is there a vibrant art scene in this part of London?

No. Nobody here except me. That’s why I like it. There used to be a printer that made artist prints, called Coriander Studios, and Damien Hirst had a big space next to him for a bit but he’s moved out now. There is industry around here, people making things. It’s not derelict, it’s quite alive—I like that. There might be some artists in another studio around the corner, but I don’t want to meet them. I want to be here on my own. I also have a studio in Menorca. I was there two weeks ago and did nothing in one sense, but I was thinking and writing.

How you feel about being interviewed, given you interviewed yourself at Frieze London in 2014 and again just this week at Tate Modern? Could you explain what was involved?

I don’t like being written about, [but] I don’t mind being interviewed. Three years ago, Frieze had a section where they did live works. They approached me and asked what I’d like to do. Off the top of my head I said I’d interview myself, so I did. It’s quite a funny idea. I can ask the questions I want to hear the answers to, I can answer them or not, or have an argument with myself. I can say things like: “Do you really think you’re the greatest living British artist in the world today?” And answer: “yes” or “no”. I changed seats and asked a question with my glasses on, answering with glasses off. You get muddled up of course. In a way it was quite spontaneous, but I had a list of questions in case I ran out of ideas.

You call yourself an action sculptor and have worked with film, printmaking, photography, painting, collage, drawing and ceramics, not to mention your live work. What does sculpture mean to you?

I like the idea of sculpture being impermanent—a gesture, or built up with a certain amount of clues, but I also like for people who look at the work to be included in it. I don’t want a work to be over there, and you, here. I made a film where I’m dancing to the song I Want My Crown by British musician Kevin Coyne. It was shown at an arts festival in Spain and I was projected life-size. People walked in front of the projection, so they were in the work. The more people that did this, the better it got; their shadows [combined] with me dancing and it was quite interesting. I like all sorts of things, glass, wood—I use whatever I fancy, whatever comes to mind. You see something, aluminium, and you think, “This sprayed yellow, I could use that” or “What would that look like on a wall or on the floor?” And off you go. It’s trying to push what sculpture is at the same time as having fun.

I love this idea of being an action sculptor, but do you reject the term performance artist?

I don’t want to talk about performance art. I think it’s something invented by the Arts Council of Great Britain [as it was then] to deal with people like me who didn’t behave properly. Jackson Pollock was known as an action painter, and there was an American singer called Johnnie Ray who I would call an action singer. I’m more interested in the gesture and the action—the thing being there one minute and not the next. I’m not interested in making things that remain in space, making a lump and leaving it there. I don’t think of what I do as art. I think of it as sculpture. Even if it’s a painting, it’s a painting made by a sculptor. The “art” is another problem, isn’t it? There was a very good programme on a couple of years ago about modern dance in the twentieth century. The people on it talked about dance but they didn’t say, “my art”, and I thought that was really good. Fred Astaire is probably one of the greatest artists of the twentieth century—he’s as good as Matisse.

“You have to challenge things all the time to keep yourself alive, to keep the spirit going, to keep amusing yourself.”

You’ve said you’re quite a good dancer…

I’m a very good dancer.

Could you say something about how dancing or movement has informed your work?

I wanted to become a dancer. I left art school when I was twenty-one without any money or materials, so I used to make sculptures by making gestures. Somebody said to me, “Why don’t you train as a dancer? You wouldn’t need any materials—you could use your body.” I tried to join the Rambert Dance Company, but they said I was too old. I was in good shape though, thin and small. I wish I’d trained as a dancer. It would’ve been good because I could have made work with my body, like the Scottish dancer, Michael Clark. There could have been some music, sound—or no sound—and it would’ve been sculpture. Ballet is very sculptural, moving around in three-dimensional space.

You gave an interview to The Guardian in 2016 where you mention the work High up on a Baroque Palazzo (1974) made with your “pose band”, and are quoted as saying: “Hardly anyone was at our most famous action, but lots of people saw the photograph. I realized that the action hardly mattered, but the photograph was really important.” In this interview you also quote a line from a John Cooper Clarke song: “If I could have one wish I’d be a photograph.” In light of these comments, how would you say photography has informed or played out in your work?

Well, High up on a Baroque Palazzo is the last piece the pose band made. We wanted to make the perfect pose and got Craigie Horsfield to take a photograph, almost prior to the thing actually taking place. We posed on this set, if you like, and thought “great, we’ve got the photograph”. There are other ways to document things apart from [through] a photograph. If you wanted to document a work, you could make a drawing of it or you could weigh it. I started to make photographs, which were sculptures. The action—the work—only existed as a photograph. It didn’t exist as me doing it, it existed as: “I’ve done it, there, click”. But I’m not interested in documenting actions, really. Sometimes you get the timing right and it all works, [but] if you record it, you still won’t get that. You need the live thing for it to work, otherwise there’s no point in doing it live.

While at art school you made sculpture from rubbish as a way to respond to what critics have called the academicism of your tutors. Have you always been intent on standing up for what you believe in and wanting to disrupt the art world?

People come out with these academic, authoritative statements about things, “You can’t do this, you can’t do that,” and you think, “Why can’t I paint a yellow stripe down the wall? I’m going to paint a yellow stripe.” I made a sculpture from rubbish in a rubbish pile, which wasn’t a comment about sculpture being rubbish. It was a material you could use. Central Saint Martins was on the wild side of things, but even that gets very academic very quickly. That’s why Gilbert and George, Barry Flanagan, Richard Long, all of us tried to shift it a bit. It’s not a question of being deliberately obtuse, but I think you have to challenge things all the time to keep yourself alive, to keep the spirit going, to keep amusing yourself.

“I don’t think of what I do as art. I think of it as sculpture. Even if it’s a painting, it’s a painting made by a sculptor.”

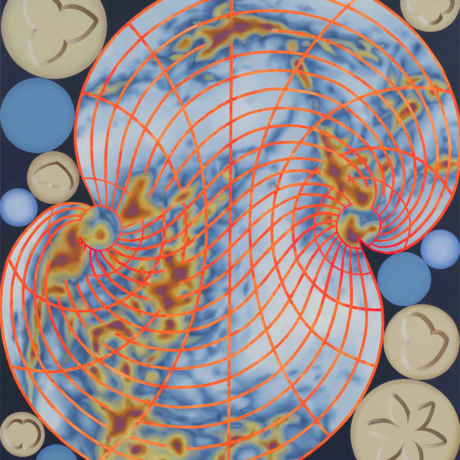

Do you have a favourite artwork of yours?

Oriental Garden, Kyoto, which won the John Moores Painting Prize in 1985. I think that’s a good work. It was one of about ten paintings I made—it was about the fifth. And then it went to pieces after that. I did it in one hit. I like to hit it in one [when making work]. It’s recorded that moment and there’s nothing else you could put in or take away that would add to or subtract from it. It’s magic, alchemy. It’s like dancing—you do it in one hit and that’s it.

A Lawnmower in the Loft by Bruce McLean

Out now with Bernard Jacobson Gallery and 21 Publishing

Photography by Benjamin McMahon