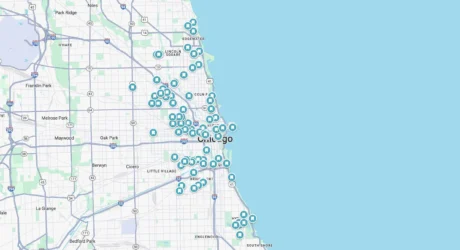

When I visit Emma Cousin’s small studio in Peckham ahead of her exhibition at Edel Assanti in London (5 July–15 August), it’s crowded with big paintings of precariously grouped figures. The show is titled Mardy—a Yorkshire term for ‘moody’ that catches the assertive and rather irreverent nature of the work. There’s also an echo of the Mardi Gras, which suits Cousin’s carnival of colourful figures acting out what she calls “the comedy of how the body works”. Cousin loves words: typically her works emerge from a colloquial phrase or saying which she explores through multiple drawings until she finds the form for a painting. The last step is to seek out a title which might, she says, “change the temperature” in the same way as a palette or gesture can.

How did you get into art?

I drew incessantly as a kid. Attending a law conference at Oxford University whilst assessing my options, I accidentally found myself in the Ruskin. The prospectus included so much drawing, theory and anatomy lessons, I was hooked. When I got home I told my mum I’d decided to be an artist not a lawyer!

So you went to Ruskin School of Art?

I was there from 2004 until 2007. Then I spent a year across a painting residency in Rome, Hungary and a job in Venice before moving to London to work for John Adams Fine Art, followed by the Robin Katz Gallery.

That was eight years’ involvement in the secondary art market through to 2016. Did that help you?

Yes, it immersed me in things—like lots of Bridget Riley, or Bomberg’s explosive flower paintings—that I might not have gravitated towards or been able to research in such depth. All that knowledge simmers somewhere in the back of my mind.

So you were painting through those years, but very much part-time?

I was always painting, but it could feel a struggle. Eventually, I got shortlisted for some prizes and that helped. I went down to three days a week at work, found a “proper” studio, and met fellow “struggling” artists at different ages and stages with whom to share critical dialogues.

And you filled your house with art?

We got the chance to buy a large but dilapidated house in Brockley. We were shopping for a bed to put in the spare room when it struck me that we could use the space more communally and usefully. That led to Bread and Jam—seven exhibitions with the brilliant Emily Austin and Rebecca Glover during 2015 and 2016, featuring one hundred artists, and taking over everywhere except our bedroom. Even the loo and the airing cupboard hosted installations. I found I loved collaborating, and that gave me the energy and confidence to focus on what I needed to make.

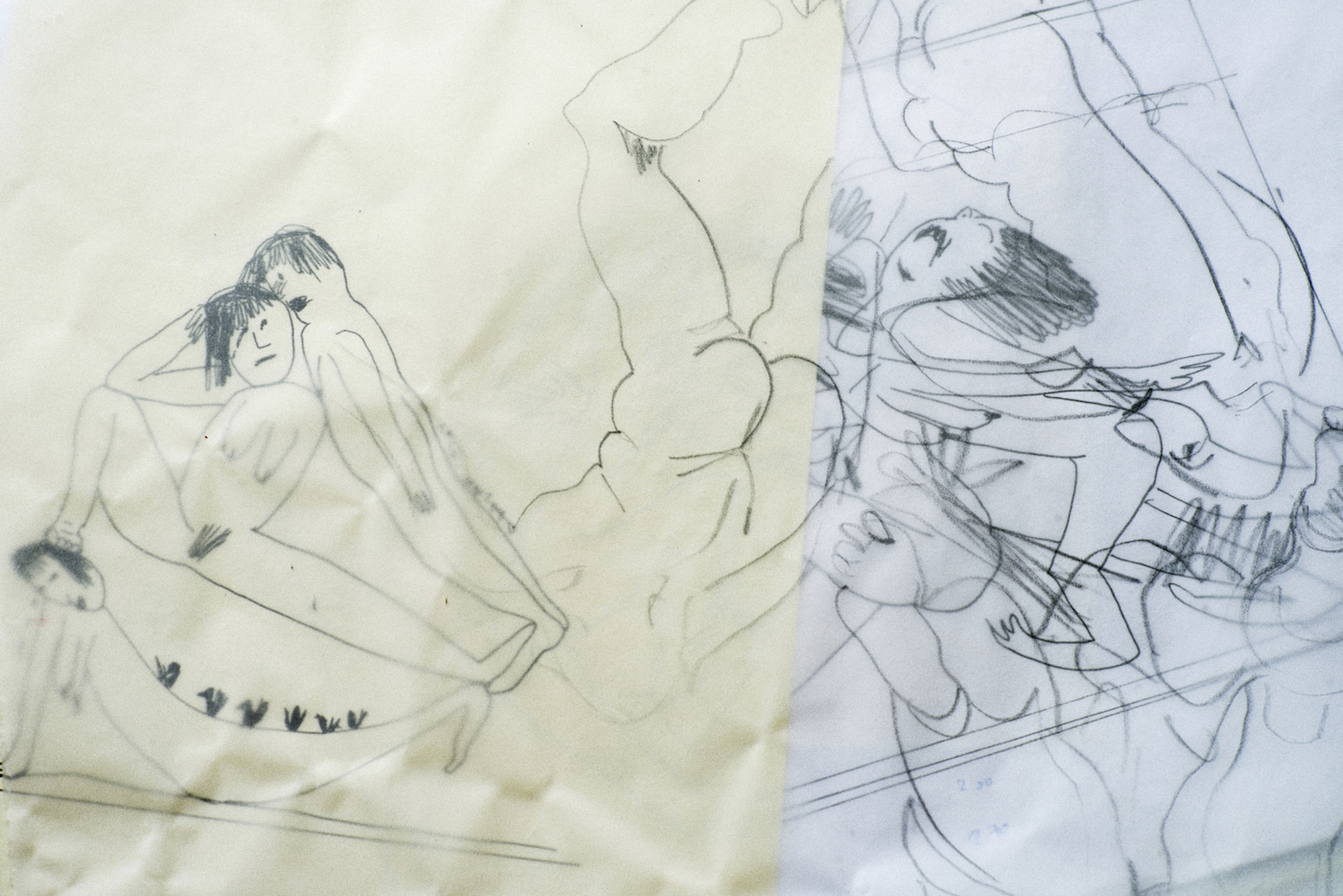

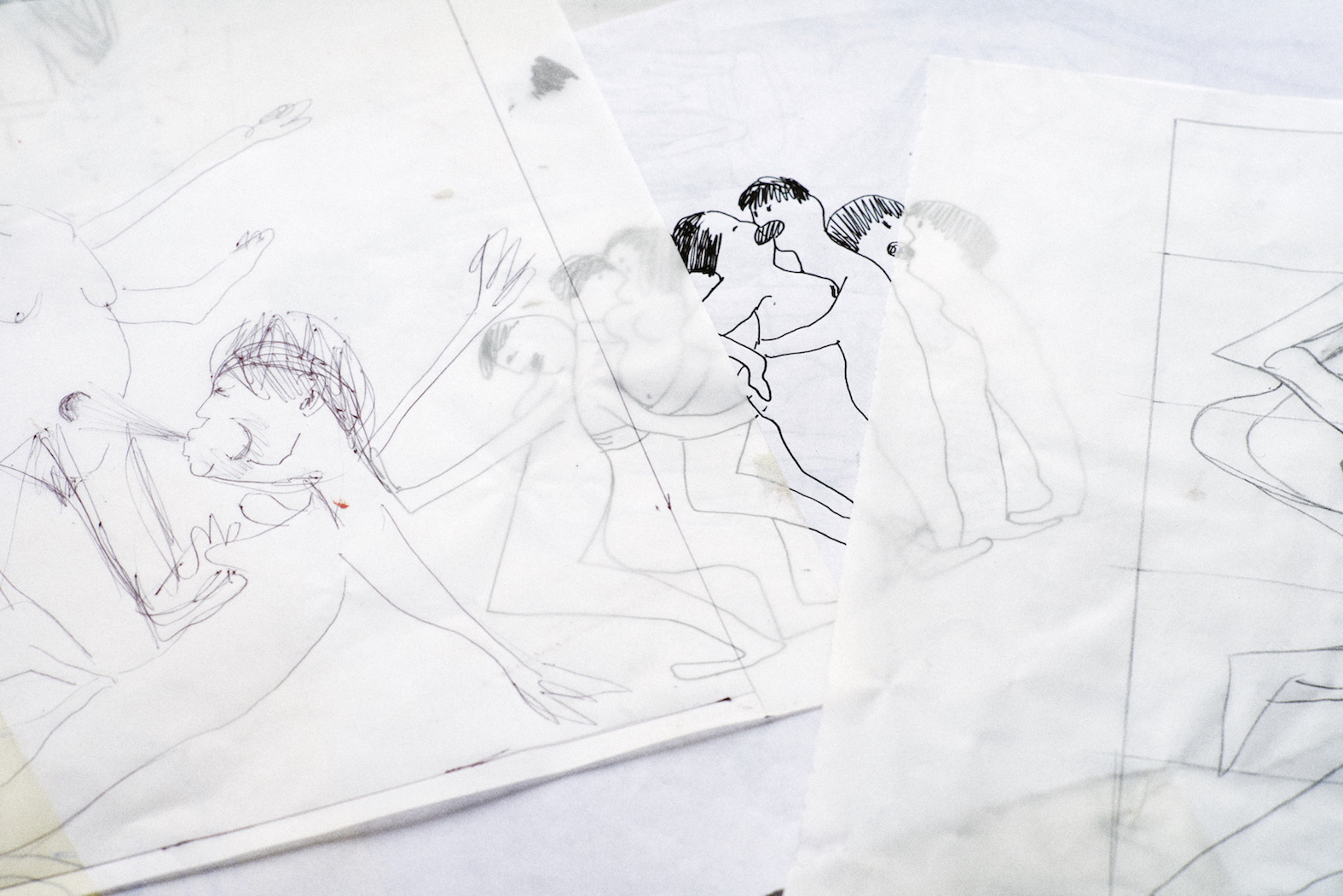

How do you start a painting?

I draw all the time, and I also write poetry: my ideas often begin from words triggering drawings. I’m really interested in line and how to bring the life of the drawing into the painting, like combining two languages.

What’s behind Hot Ribena, for example?

I thought about how a character might be turned on and off emotionally, physically and psychologically… and might malfunction in some way, like a washing machine which responds automatically for years then suddenly doesn’t. How much can we control our functions? Where would those buttons be? Between legs, but also the belly button, the boobs, the eyes as goggles… suddenly you have a body full of buttons. The title takes me back to sensations: warming up after freezing in the snow, being sick as a kid—as well as arguments over how strong to make the Ribena!

People and their bodies seem to be your subject?

I use the body, or groups of bodies, to build a structure, to present “status changes”: like mobility, clothes and aging. The groups might fail—are they going to topple over or fall apart? There’s an implicit danger, a relationship between the figures which could go either way—to provide a support system, or to pull each other to pieces. I’m curious about our expectations of our bodies and judgements of other bodies. I’m testing their limits and interested in putting the bodies at risk. They exist in a liminal space which is a place of discomfort, an edge or a boundary. A space between us and not us.

Are they self-portraits of a sort?

No, they may be the same person recurring, or different elements of a self, and they’re from my perspective—but they’re not me. I see these bodies as universal, starting from the idea of identity as unstable. That’s why the spaces have no props or information—the figures have no coordinates in the space, their only anchor is the structure of themselves or possibly an overstretched forefinger groping for the edge of the canvas.

Why do your figures tend to be naked?

Skin is great to paint. It enables them to wear the “same uniform”. And I’m alert to the information it can hold—age, health, gender, genetics. It is also the source of much of the tension in the work, pulled, stretched or squashed to produce a feeling. These bodies are awkward, uncomfortable, stacked, stretched.

But there are skirts in Bracken and Black Adders—why?

Clothes aren’t off limits! The original thought for this painting was the difficulty of wearing a skirt—sitting down, cycling, etc. Then whilst I was making it “upskirting” was in the news. I thought how young girls in a more innocent context will lift their skirt up to gain attention, or just show you their tummy. The irony is the skirts here are not concealing anything. The title refers to bristling undergrowth and the danger of adders (I walked a lot as a kid on the Moors and this was a clear and present danger to the naked arse!). But you don’t need to know that—I’m more interested in how the words make the viewer feel.

Why the small hands of one figure?

That felt right as a way to emphasize the pincer action. I’m not after realism, no one poses for the paintings. Though I sometimes make drawings from life to get it to read right. It’s more about how things feel from the inside than how they look from the outside.

What’s going on in Black Marigolds?

That came from the phrase “the blind leading the blind”, the idea of trying to help someone I care deeply about when neither of us were sure how to or what to do. These figures are trying to assist each other but going nowhere—pulling against one another as they are stuck. But supporting each other too. The dark background suggests they can’t see. I was thinking of three blind mice, so it’s particularly pinkish flesh and their nipples become beady eyes.

What’s next for you?

I’m spending nine weeks at an intensive residency programme in Skowhegan, Maine. It was established in 1946 and alumni include Alex Katz, Ellsworth Kelly and Peter Saul—a great opportunity even if I’ll miss my own opening at Edel Assanti! While away, I plan to work towards the Jerwood Survey Exhibition, which runs from 3 October until 16 December.

All images © Tim Smyth