Gracing the cover of our current, newly designed issue, is a photograph by Eva O’Leary. The arresting red hair and scintillating blue backdrop, contrasting with the wallflower pose of the image’s adolescent subject, typifies the series it belongs to, Spitting Image, shot using a two-way mirror and completed this year. It was the ideal picture for our magazine, in the way it confronts how agency, perfectionism, youth and identity are conventionally used by the media, and the insidious commercial gaze. O’Leary’s attitude as an artist, candid and unaffected, is also something we appreciate, as we found out when we paid her a studio visit in New York.

Congratulations on your Elephant cover! Are you happy with it?

Yes, I’m so happy with it. Thank you! It’s the first time my work has been on the cover of a magazine.

Can you tell us a bit more about that image, Redhead (Amie), and that particular shoot?

I made this photograph during my first year at Yale. At the time, I was approaching my work in a highly intuitive way. I was walking down the boardwalk at a public beach and saw a young girl walking towards me with her family. She seemed to be folded into herself, hiding, her hair covering her face. I found it hard to imagine that she could see where she was going. I felt so self-conscious at the time, both in graduate school and as a woman in the world. I really saw myself in her.

What have you been working on since we interviewed you for the issue?

I left New York for almost two months and went back to my hometown. It’s a small town in Central Pennsylvania, also nicknamed Happy Valley (home to Penn State University). I wanted to start a new project out there, something I had been planning for a while. When I left, I had a pretty concrete idea of what I wanted to make next. I started that work, but something wasn’t sitting right, so I put it aside. I had concerns about the project, what it was saying about women, how I was relating to the individuals I was photographing. I became extremely frustrated. After two weeks of banging my head against a wall, I started working on something completely different. In many ways, this new work grew out of that frustration, the contradictions I was struggling with and the questions I couldn’t answer.

I don’t want to say too much about this new project since the work is still evolving. But it feels very different, and I’m really excited about where it’s going. There’s a lot of trust involved. I have to lose a certain amount of control, remind myself to be present and really believe that the pictures will come. I’m trying to let my subjects show me the pictures; in many ways, they know far more than I do about where this work is going. While this is a source of anxiety, it’s also incredibly exciting because it feels like I’m in a place of constant discovery. I’m finding that the project keeps raising more questions, there’s a lot to dig through and a lot I don’t understand.

I’m intrigued! When you are in New York, what is your life like in the studio, usually? Do you have a routine?

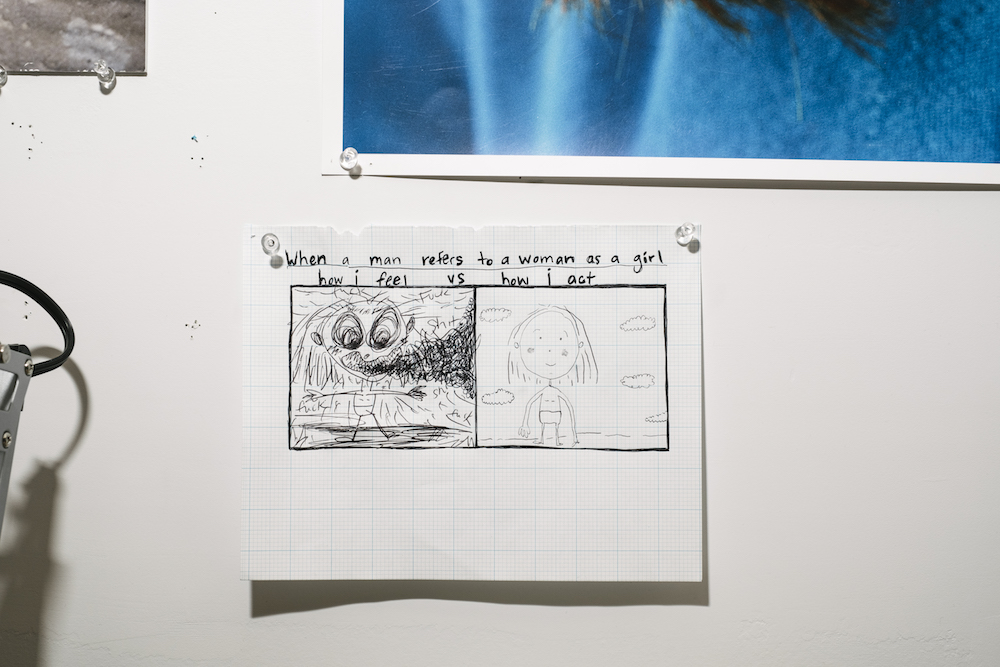

I think it’s important to acknowledge that artists are not production machines. There’s this pressure spurred on by the internet and social media to be an effortless machine that pumps out new projects on a weekly basis for public consumption. A content generator. I have few studio lives and a few routines. There are a lot of things that go on behind the scenes that are not at all glamorous and do not result in visual proof of productivity.

In New York there are days where all I do is check my email, respond, try to set up shoots, make sure I’m not missing important deadlines. There are days where I’m just trying to figure out how to afford to buy groceries. There are days where I work really hard to be self-aware, critical and see through the fog that envelopes my habits and feelings. There are days where I feel overwhelmed with what I’m trying to take on.

There are also days where I’m traveling and observing, seeing everything as valuable information, data, dots that can be connected. Making sense of what I see, my place in the world and how I’ve come to understand it. The best days are the ones when I’m actively making pictures, where I feel like I’m directly interacting with the world and finding meaning in it. This gets me through all of the other stuff. But the less glamorous days make these days possible and productive.

“I’m really sick of the braggadocio professionalism you see online. People are afraid to be human, afraid to be vulnerable.”

I’m really sick of the braggadocio professionalism you see online. People are afraid to be human, afraid to be vulnerable. A major part of being an artist is producing physical (or some kind of) work, obviously. But a lot of it involves making sense of the world around you, absorbing it, translating it, mentally mashing things together and finding meaning. This process can take many forms and is not always pretty, visible or sellable.

I’m really glad you’ve raised that, I think it’s very important to remember. To go back to what you were saying before about your new project, you talk to Ariela Gittlen in your interview in our print issue about photographing women, and young women in particular, as a female photographer, and how you avoided it for a while. Do you feel women photograph women differently?

I don’t believe in generalizations, especially generalizations about gender. I think a portrait is essentially a document of an exchange. The dynamics between photographer and subject alters the image, in my opinion, there’s no way around this… it’s all a negotiation.

Obviously, a large part of the image relies on the subject. The model imagines what the photographer wants. You (the model) are trying to give them the image they desire, what you think they desire. So that changes your behaviour and your positioning. I’m very aware of this when I’m being photographed. You create this internal image of yourself. You look at the photographer facing you—how they dress, how they speak to you, how they act towards you, their body language, if they are flirting, if they are scary, if they are self-deprecating, if they are friendly… Do they make you feel comfortable? etc. All of this is useful information that instructs me, as a subject, how to position myself. This dynamic informs my body language, how I either conceal or display my true emotions. And as a photographer who often photographs people, knowing this is key. It changes how you carry yourself, how you come across and how you relate back to your subject.

“Photography lets me study the things that upset me, confuse me, terrify me, all in a really specific and incredible way. It lets me interact with the world directly, really interact with it.”

I think historically we’re used to seeing a particular dynamic between photographer and subject. Especially between a cis male photographer and a cis female model. As a society, we are comfortable with these dynamics and how they translate photographically (actually, I’m very uncomfortable with these dynamics. To me, they are mostly about power). I think it’s exciting to see pictures made by individuals who relate to their subjects in new, less predictable ways.

I agree! And yes, there is a power dynamic we’re used to being interpreted through the camera for sure. I guess I feel that power dynamic is disrupted (though of course not always) when it’s a woman behind the lens, as we relate differently to people, men and women.

What do you enjoy most about what you do, as an artist?

Making work gives me an excuse to interact with the world in a way that feels meaningful. And joyful. And it takes the sting out. When I was younger I was obsessed with psychology. When I was in high school, I’d walk to the Penn State Library and tuck myself away in the psychology wing, reading case study after case study. In the world outside the library, I always felt like an alien, like I didn’t fit in. Reading about psychological ailments was a way to understand human behaviour and pain (and in turn my own behaviour) on a much deeper level. It gave me some relief. It made me feel less alone.

Photography lets me study the things that upset me, confuse me, terrify me, all in a really specific and incredible way. It lets me interact with the world directly, really interact with it. Just like my case study obsession, making work gives me a tool to understand human behaviour and pain on a deeper level, and with that, selfishly, I get relief.

When I’m not making work, I become overwhelmed by the bad things. And the horrible things. And the things that no one else feels but I do (but you know everyone else probably feels these things too). Sometimes these feelings are abstract, existing as large insurmountable emotions. Hard to put your finger on. They just are. There’s no alternative. There’s no explanation. There’s no magic. There’s no reason for any of it. There’s no trying to understand on a deeper level and then finding freedom in that understanding. Making work gives me a sense of agency, it gives me this excuse to try to understand the parts of my life that otherwise would terrify, depress or leave me feeling isolated. If you understand something, you can free yourself from it.

Read more about Eva O’Leary in Issue 32

Images © Donald Stahl