Peake’s current exhibition at Studio Leigh—RITE—seeks to reinterpret Igor Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring (1913) as a performative sculpture. She is showing ceramics, paintings and video works, produced in partnership with CASS Sculpture Foundation during the CASS Projects residency programme with West Dean College. The second part of the Rite of Spring project culminates at the De La Warr Pavilion in Spring 2018. Peake’s collaborative exhibition with Tai Shani, Andromedan Sad Girl at Wysing Arts Centre, is also currently on show. Drawing on mythology and the structures of feminism, their immersive installation imagines what a pre- or post-patriarchal civilization could look like. Peake’s work often centres on the primal body and spiritual practices, believing that materials have their own vocabulary, autonomy and subjectivity. I met the artist in her studio at Somerset House to talk about intimacy, material empathy and artistic collaboration.

“Sculpture and performance are very collaborative to me, but painting is very private.”

What is it like at Somerset House Studios? Has it afforded any new opportunities or ways of working?

It’s amazing. There is a mass of really talented thinkers and artists here, especially in this particular studio. I share a space with Mel Brimfield, who is a visual artist but also a theatre maker, Phoebe Davis, who works in live art, performance and sex education, and Project O, who do very politically radical work. Having a space in the centre of town, and the time afforded by that, is also fantastic. When I’m performing and teaching I have to be permanently switched on, so I love the wonderful, private feeling of working in a studio space. I work in bursts of great intensity when I’m here. I was working very intensely in March, April and May. Then through the summer there was a lot of back-to-back external production on the Rite of Spring project and Andromedan Sad Girl. Somerset House Studios let me use their huge gym and dance studio, at this amazing reduced fee. I took my dancers and four tonnes of clay into the space to work there. We had to lay all this protective sheeting down. It was really terrifying lifting the floor up at the end! I’ve got about one and a half tonnes of clay left, if you know anyone who needs any! I did have dancers rolling around in it naked for three weeks though, so you will find the odd pube!

In your recent

Bosse & Baum show, We Perform I Am in Love with My Body, you exhibited a series of paintings that explored the sensation of falling, by outlining the moving body. How does performance intersect with other facets of your practice? What is the feedback between live work and static objects—do they inform one another?

There is a lot of discourse around the idea of kinesthetic empathy, the idea that when we dance or watch someone dance there are things being fired in our brain, that we are moving ourselves and that we have an empathy with movement. I am curious about how you do that with a 2D object or a floor. I like that there might be an object that is produced via a performative gesture or act. You could say that all painting or making is performative. At Bosse & Baum during the live durational performance, we drew around ourselves using the methodology I had followed for the original paintings. It was really exciting, to re-perform that gesture again.

“How do you perform erotic intimacy, how do you perform the tricky moments of relationships?”

It also converges the perhaps more private act of painting and drawing with public choreography. Your work often generates an intimate moment of shared space with your audience.

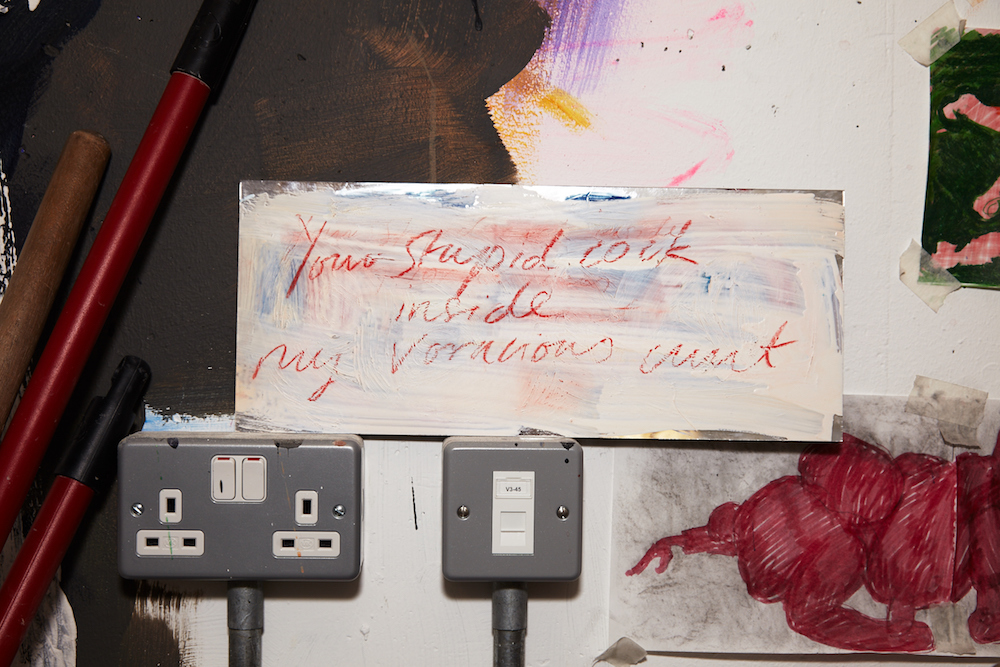

Sculpture and performance are very collaborative to me, but painting is very private. Directing a team of dancers requires a different energy and way of engaging. I’ve actually started a new project with my girlfriend Eve Stainton, looking at this idea of performing intimacies, and where the professional and the private blur. How do you perform erotic intimacy, how do you perform the tricky moments of relationships? I learn so much through collaborating with other artists; it helps me expand my practice. Sometimes it’s painful or emotionally challenging. It’s different when you are collaborating with a filmmaker or a lighting designer, but when you’re devising work or making a project together, when the authorship is shared, it’s harder. I also work with the artist Catherine Hoffman. We have a band called Sex Music, which is a stand-up comedy band. It can be very passionate, especially when we are juggling other separate projects.

Can you talk more about the Studio Leigh exhibition, which is the first stage of your ongoing Rite of Spring project, which culminates at De La Warr Pavilion next year?

It’s a sculptural interpretation of Igor Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring, which is an iconic score and monument of modernist history. There has been a huge canon of choreographers that have done The Rite of Spring, from Pina Bausch to Jérôme Bel. I wanted to sidestep that. I think of this interpretation as sculptural, framed within a visual art context. I also want to think about how we can work with The Rite of Spring as a protest against fascism. It’s been just over one hundred years since the infamous riot on the opening night in Paris in 1913. It mirrors the time we are in now, with the fracturing of Europe and the rise of fascism. I want to draw parallels across history, thinking about how the themes of The Rite of Spring—the primal body, fertility and sacrifice—are possibly relevant today. Those are the questions at the heart of it, but I want to think about how those ideas can be embedded into the material of clay, and all the different possibilities with the moving body. I’ve been interested in the idea of a stage or platform as a space that gets acted upon. So, we made this clay stage with the choreographer and dancer Rosemary Lee. She memorized the music with her body, and then performed it as a protest, into this object. We then fired that floor and glazed it, and it’s become this polyrhythmic and discordant object, like the soundtrack in the show. That’s the centrepiece at Studio Leigh, and then there are other supporting pieces, like the film of her doing the performance and other drawing works. Then in the spring, the Rite of Spring project in full will open at De La Warr Pavilion. There will be a three-day performance. The first two days are slow-paced and durational, and the third day will be a sit-down, hour-long, climatic and explosive performance. Lots of clay. The audience have to wear waterproof ponchos.

Another political concern in your work has been the commodification of art by the corporate world.

Yes, the project in which I really addressed that was The Keeners

(2015), which asked how on earth do you make art—now—when everything feels like it gets consumed, when images feel so disposable? How can an image have significance? Images can feel quite empty these days, we get fed them the whole time. Keening is from the Irish-Celtic tradition, [a keener] was someone who could support and aid losses, and mourn on behalf of people. I wondered what keening for cultural losses could be like. I think there is a lot of loss and grief for artists working with materials. The corporate world has changed our modes of making. My interest in modernism comes from a sense of earnestness. These great modernist choreographers really believed that what they were doing meant something and could change something. Today, sometimes our actions feel futile or empty. When we perform this act, or when I create this thing with clay, how can I create a feeling that resonates or has an impact?

Photography © Tim Smyth