The kids in the office look impressed when I tell them I’m off to meet Gilbert & George. They say they’re a bit like Ant & Dec, aren’t they?—by which they mean they don’t know which one is which—but they express unalloyed admiration for their 1969 double self-portrait George Is A Cunt And Gilbert Is A Shit. It’s cool. Properly deployed, it could also help them to identify which one is Gilbert and which one is George since it overwrites the artists’ individual portraits with their names. But I’m far too well-mannered to mention that.

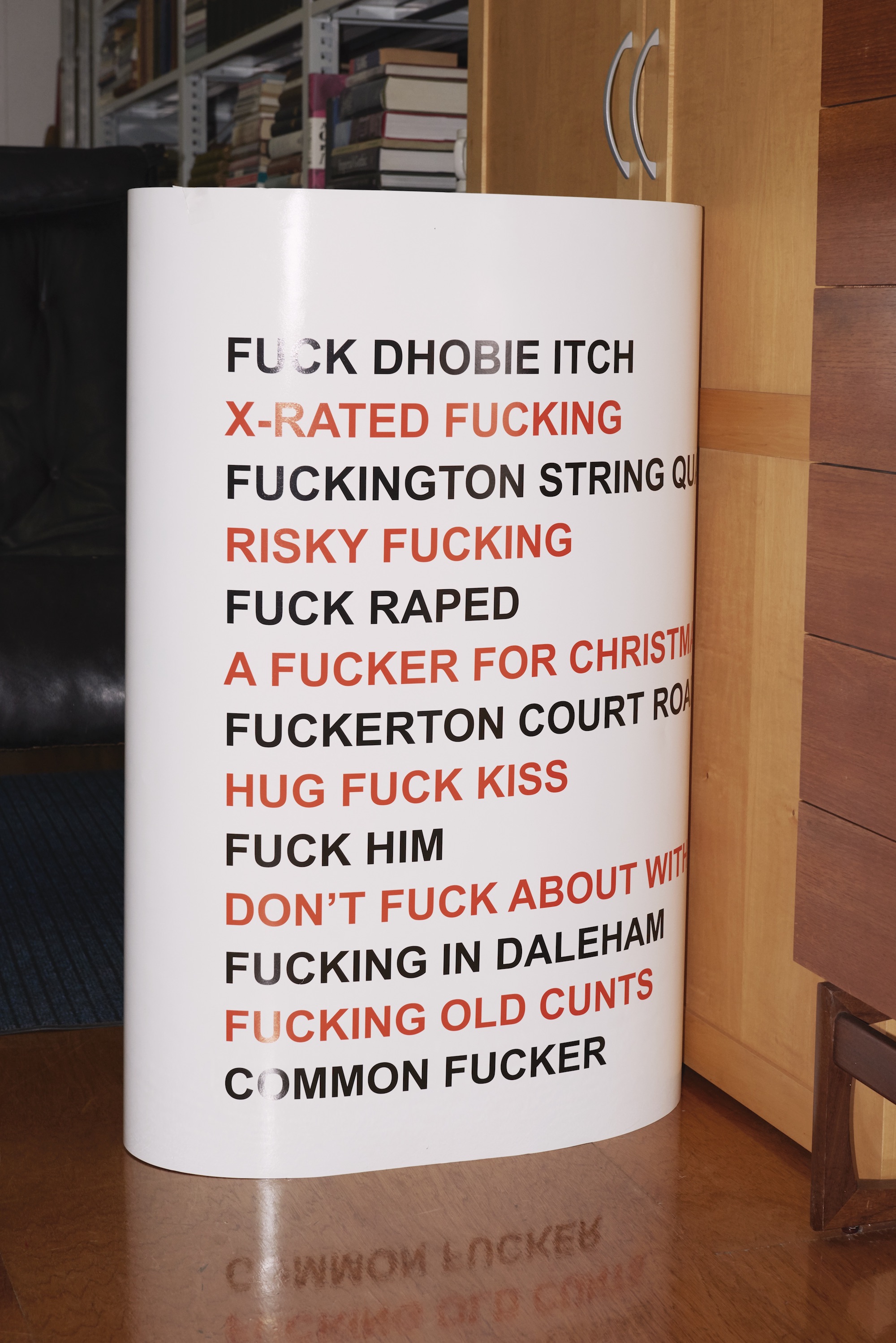

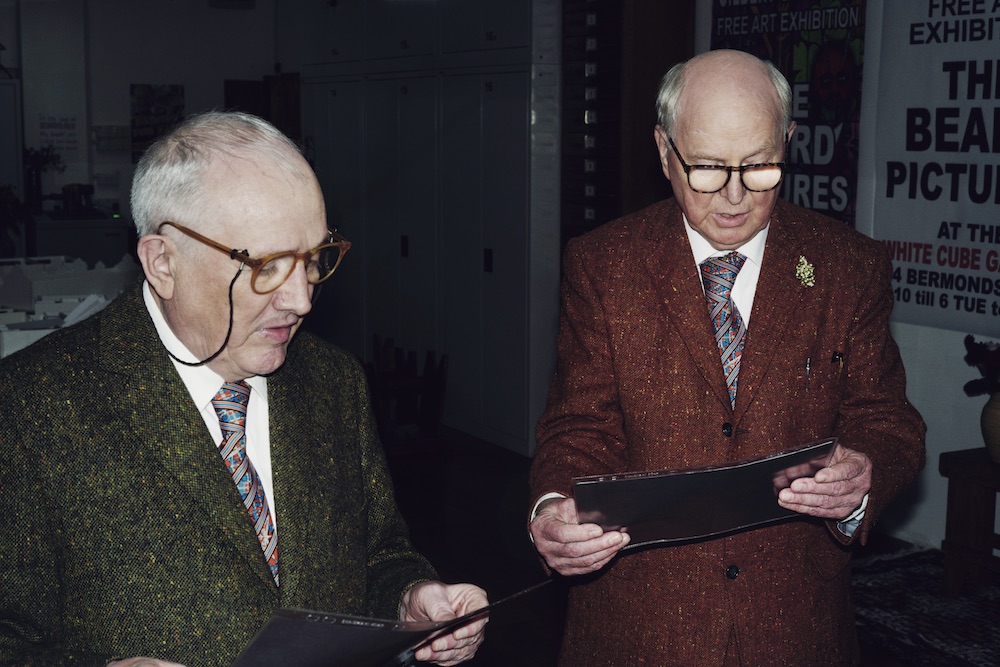

Good manners are something Gilbert & George understand too. The eternally besuited duo greet us courteously at the front door when we (I’m accompanied by our photographer, Benjamin McMahon) reach their studio-home, an eighteenth-century townhouse located in the shadow of Spitalfields Market and the spire of Hawksmoor’s Christ Church. Now in their mid-70s, the pair (for the record, George is the tall, English one, Gilbert the smaller, Italian one) are on the point of launching a mammoth sequence of exhibitions centred on a new photo-based series of works, THE BEARD PICTURES, beginning at Lehmann Maupin in New York. There’s also a book, What Is Gilbert & George?, and their Fuckosophy, a collection of around 4,000 phrases containing the word “fuck”. Well-mannered they may be, but they do enjoy a good swear.

“People think it’s done by a computer, it’s not. It’s done by our heads, our souls and our sex.”

How or where do they gather the sayings—do they write down overheard nuggets when they’re on their jaunts around London? No, they say, that would be too boring—all “fucking car’s bashed in” and the like. Instead they carry sheets of cardboard in their elegantly tailored pockets and write down f-word-flavoured phrases as they come into their heads: “Fuck + let fuck”, “Very fucksexfull”, “Yours fuckersly”.

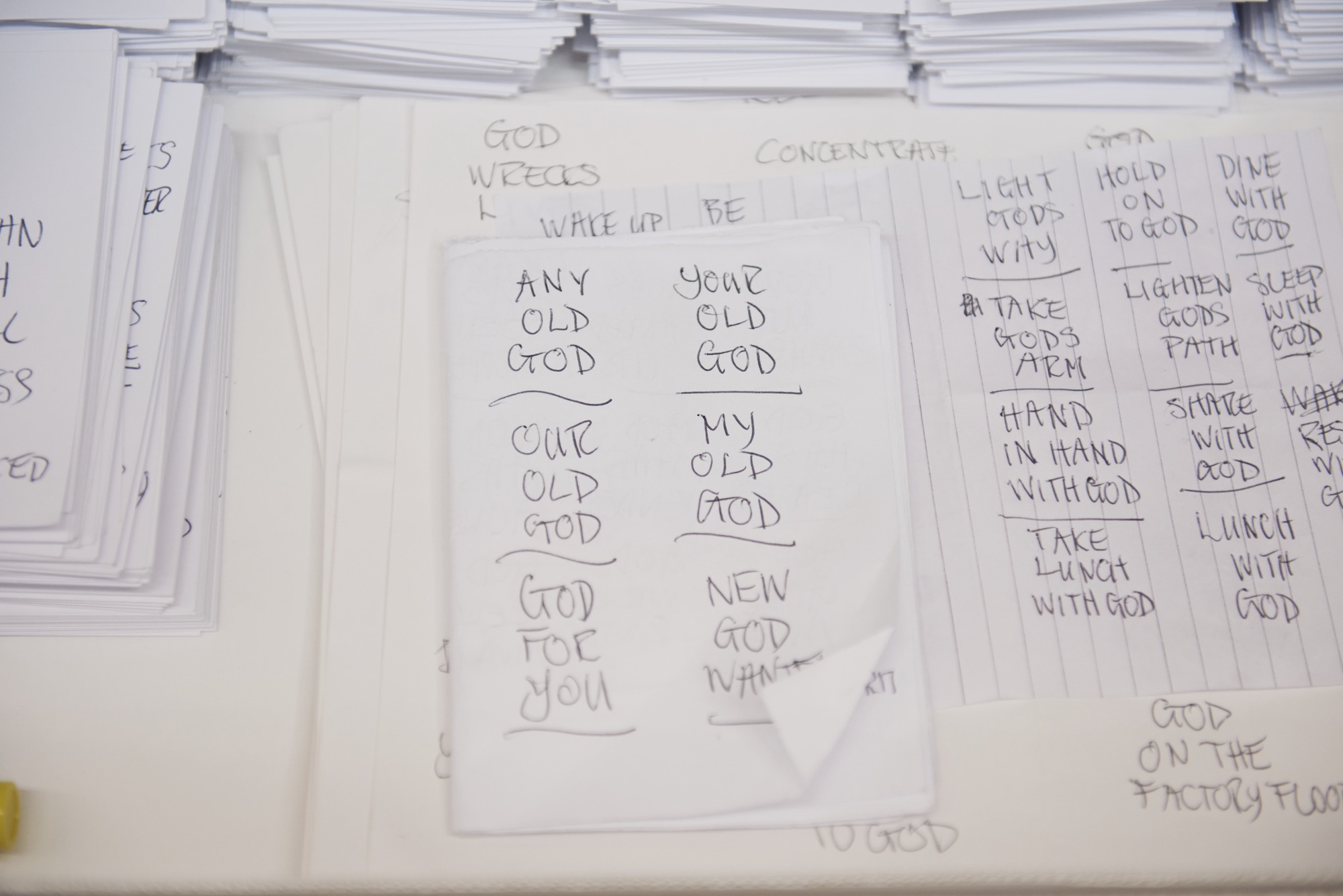

Now that the Fuckosophy is finished they’re working on their Godology. “After that, there’s nothing really,” says George as they give me an impromptu taster of their work-in-progress.

George: “Only God counts.”

Gilbert: “Forgive not God.”

George: “Dear sweet God.”

Gilbert: “God of all of you.”

George: “God of death.”

The recitation continues: “God bless the Isle of Man… God bless shit.” “We don’t believe in God,” concludes Gilbert as they lead us off on a tour of their home. There’s fine period furniture, an eccentric coat of arms, quirky books (a vintage volume by the pacifist Vera Brittain with an amazing, and presumably unintentional, S&M cover) and, somewhat jarringly as we return to the studio, a Paul O’Grady welcome mat. “He sent it to us as a present,” says George.

Have I fallen down a rabbit hole, I wonder. Is this the sort of episode that inspired Alice in Wonderland? Am I Alice? Is Gilbert the White Rabbit?

The studio is large but the artists don’t employ a large retinue of assistants to do the work for them. “Everything that is art is done by us,” says Gilbert. “Everything that is not art is done by somebody else.”

There are several computers. So some of your work is done by computer, I say.

“People think it’s done by a computer, it’s not. It’s done by our heads, our souls and our sex,” George corrects me, courteously. “People don’t do a drawing with a pencil. It’s done by their heads, their souls and their sex.”

There are billions of computers, says Gilbert. But none of them is making pictures quite like theirs.

So their work is not done by computers.

Your new works celebrate beards, I say, getting down to the nitty-gritty. And yet neither of you has one.

“Certainly not,” says George. “What do you think we are, scruffy artists?”

We sit down and Gilbert shows me a place card for one of their forthcoming launch events. “Read it out!” George instructs me gleefully. Are they testing me, to see whether I’m embarrassed to swear? I am not! “Dinner with fucking Gilbert & George,” I begin, “at fucking White Cube Bermondsey…”

It’s almost exactly fifty years to the day since war babies George and Gilbert first met, as students at St Martin’s School of Art in London in 1967. Collaborations of this kind and longevity are extremely rare in the art world, I observe. “But it’s very common outside of the creative field,” says George. “The world is full of twosomes, it’s the most common unit. There’s usually great inequality involved, historically, which we’ve managed to avoid.”

The art they began to make together—as anti-elitist living sculptures, producing work for the ordinary people despised by most of their college tutors—led them away from formal concerns. “That felt inhuman for us,” says Gilbert. “Oscar Wilde said: ‘Art for art’s sake.’ We say: ‘Art for life’s sake.’”

“Unlike most of the students at art schools we weren’t middle class,” explains George, “so we didn’t have the safety net that they have: they can always go back and work on dad’s pig farm or something like that. We didn’t have that. We had to win.”

These outsiders with a very relatable story have always been driven by a desire to win. “The enemy were very helpful, that’s for sure,” George says. This enemy included “certain” members of the liberal art world and the establishment, they say, fishing for their favoured characterization of the Other—“the intolerant liberals”. They have always enjoyed support from the general public, they say, something they are particularly proud of. What really matters is the approval of ordinary people, and younger people.

This makes me think of the kids in the office and a fresh line of questioning suggests itself.

“Have you ever said to yourselves: We could be Ant & Dec?”

“They copied us,” laughs Gilbert.

“We never wanted to be television stars. It’s a great privilege to be an artist,” offers George.

“It’s very good because we are some kind of anarchic outside,” continues Gilbert. “Total freedom for ourselves. We are not responsible for the world at all. We are free. We don’t have to look to television or the BBC to do something. We do it alone.”

They do WATCH television, though, as I discover when we indulge in an enjoyable digression on places, during which I announce that I am from Mansfield (a compulsion of mine). George says he thinks Mansfield is in Yorkshire. It is not, I correct him, also courteously (I hope), it is a scab mining town in Nottinghamshire. “We know Yorkshire because we watch Heartbeat,” says Gilbert. “We watch it every night.” George puts on a Yorkshire accent to demonstrate. I mention the famous Yorkshire cricketer Geoffrey Boycott, but they claim never to have heard of him. Apparently they don’t even know the rules of cricket. “We never watch sports,” says Gilbert.

“We’re not anti-things. If people come to the door to ask us to sign AGAINST something, we’ll never do that.”

We live in difficult times, and Gilbert & George are hardly frightened to reflect difficult themes in their work. Nonetheless they describe themselves as optimists.

“We’re not anti- things,” George explains. “If people come to the door to ask us to sign AGAINST something, we’ll never do that. If it’s FOR something, we’ll sign anything. We don’t even read it if it’s for something. We’ve probably signed for some dreadful things,” he laughs. “We don’t have time to be against things.”

“We went to a restaurant in North London where we love to go in the evenings, and we went by chance for lunch,” he continues. “Nearly everybody there was thirtysomething, they were all plump and they talked only about foreign holidays. The whole restaurant. Extraordinary. ‘We’re having four days in Italy.’ ‘We’re flying with friends.’” The scene offered quite a contrast to his own youth in postwar Plymouth. “The only people in my family who went abroad went to fight.”

Back to beards, which, as the title suggests, form the crux of their new series of works, THE BEARD PICTURES. Religious beards, hipster beards—“It’s all part of a revolution: allowed/not allowed,” says Gilbert.

“You wouldn’t get a job if you had a beard as a young person in my hometown,” says George. “In the forces you could only have a beard in the navy. You could have a moustache in the air force.”

“All of the images are taken by us,” they say of the new works. These feature a lot of barbed wire and fencing, which they bought and then photographed in their studio, as well as burglar alarms, which they photographed as they walked around London. “The world is spending more on security now than in the history of mankind. It’s massive,” says George. They also found themselves photographing leaves, which, they came to realize, often look like a bit like beards.

How do they go about composing the final images from these diverse source materials?

“They [the images] have to, as near as possible, make themselves,” says George. “We try not to interfere. When we go through those drawers we try not to say: Today we’ll do them green with monkeys or red with fish. Just empty the brain. You still are you inside even if you close down. You still know what you are and what you think of the world. Try to make it that.”

On the table next to us is a maquette of the foundation the duo are planning to open nearby in a few years as a space in which to show their work. Gilbert suggests the Soane museum as a parallel. They are frustrated by the lack of attention their oeuvre now receives from the big public institutions in London.

There’s something a bit maudlin about planning their own foundation, isn’t there? Do they feel older?

“Not yet,” says George.

“Maybe the legs are giving way,” says Gilbert.

But you are thinking about your legacy? “Very much,” says George. Not that they have much time to dwell on such things. Their schedule is already full until next summer.

They like the thought of winning fans among the younger generation, so I tell them the kids in the office can really relate to George Is A Cunt And Gilbert Is A Shit, and George becomes a bit misty-eyed as he then recounts taking the negatives from the shoot to be developed on Oxford Street in 1969. When they went to collect the prints the following day, the man behind the counter handed them over and told them steelily never to return. “That’s when we knew we were on to something,” George nods.

It’s time to leave. I fear we’re in danger of outstaying our welcome, I say as we gather our bags. Not a bit of it, the artists insist, although George can’t resist telling us what he likes to say when he wants to get rid of people. “I say it’s time for me to masturbate and have a cup of tea.”

And with that we pass again through the front door, out of Wonderland and back into the street.

THE BEARD PICTURES

12 October until 22 December at Lehmann Maupin, New York

gilbertandgeorge.co.uk

Photography by Benjamin McMahon