Heike-Karin Föll’s Berlin studio is behind brick walls graffitied with the apparently desultory markings of a hand working fast, possibly late at night. It’s an apt introduction to an artist who builds her own language. As a child, Föll suffered from acalculia, a condition that impaired her ability to perform simple mathematic calculations, which made her see numbers as shapes, and develop her own system of logic, which pervades her work: letters and markings jump onto her canvases among her brushstrokes, and her books become hand-held paintings. She might be “a gallerist’s worst nightmare,” but Föll is devoted to thinking, and rethinking, the meaning of art and the messages different mediums might convey. Above all, it’s playing with words, and paint, that appeals to the German artist.

You have had such an eclectic output over the years across Berlin: teaching at the UDK (Universität der Künste), but also participating in directing at spaces such as basso, the Volksbühne Glass Pavilion on Rosa-Luxemburg-Platz and Allgirls gallery. I imagine it’s quite rare for people to see you in your studio. You have quite a unique practice, which also has a very intimate side, surrounding yourself with words and books as well as drawings and paintings. What have you been working on at the moment?

Well, I am a painter, who writes as well. I just finished a piece called Synopsis for a 70s Sci-Fi Movie Never to Be Realized. Funnily enough, I was approached to produce it, but I just decided yesterday “no”. It’s not meant to be released, I really love this idea of the unreliable author. This for me is absolutely liberating, the idea of becoming unreliable. I find that as a painter one must remain as free as possible and at times this means not taking responsibility.

And how does this irresponsible manner manifest in the work?

It’s in everything. When you look around this studio it’s just the tip of the iceberg. To be able to play is really important. Going against the grain, not directing everything or controlling everything, which is usually the demand. You are always told you have to name it, you have to be able to talk about it, all these meta-levels sometimes have to be forgotten in order to move or to go on. You have to push yourself into a space of distance, hence I find myself in the studio-cum-ivory tower these days.

Is the studio both a privilege and a necessity for you?

Yes, to be alone is quite something and no doubt it’s a privilege, but it’s also a demand. This is also why the studio environment has been so heavily criticized. It can become quite limiting and the artist certainly can fall into the trap of the ivory tower. But if your work also has an outside, beyond the studio, it can be extremely valuable to have this closed-off space.

In a way, your physical and conceptual ideology centers a lot around rejecting enforced infrastructures.

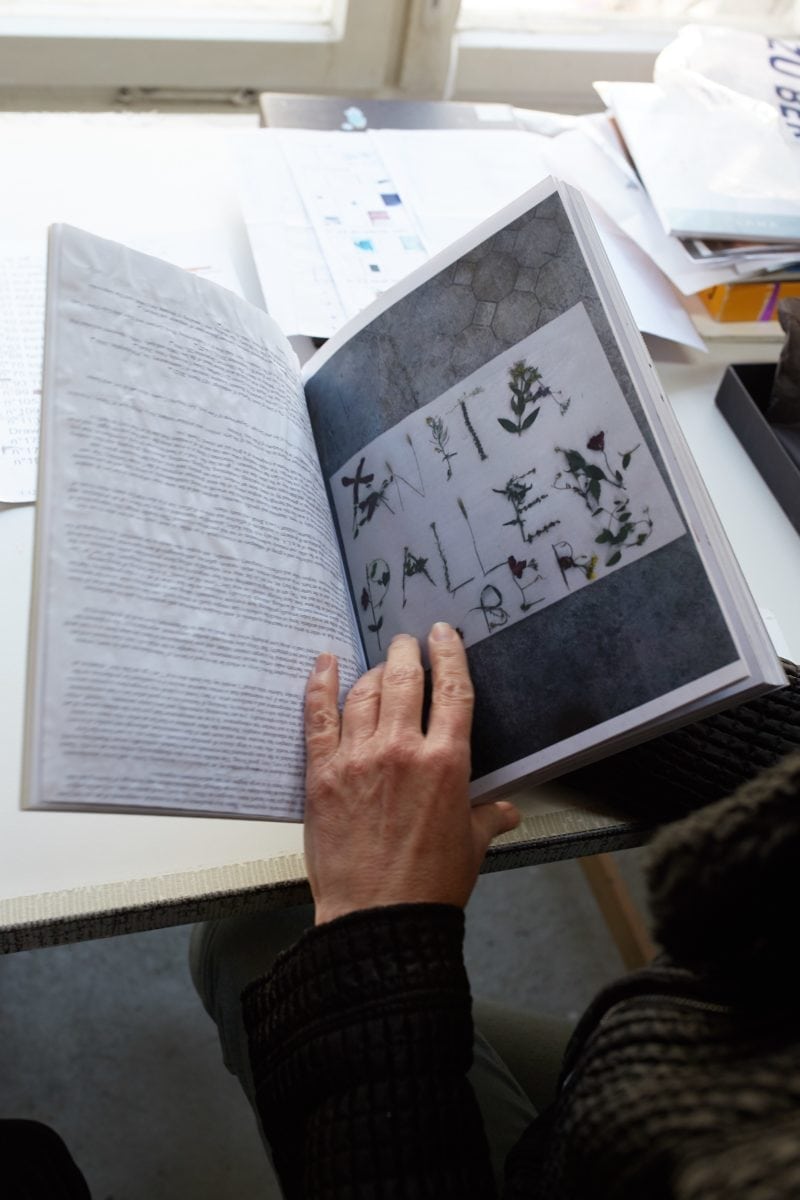

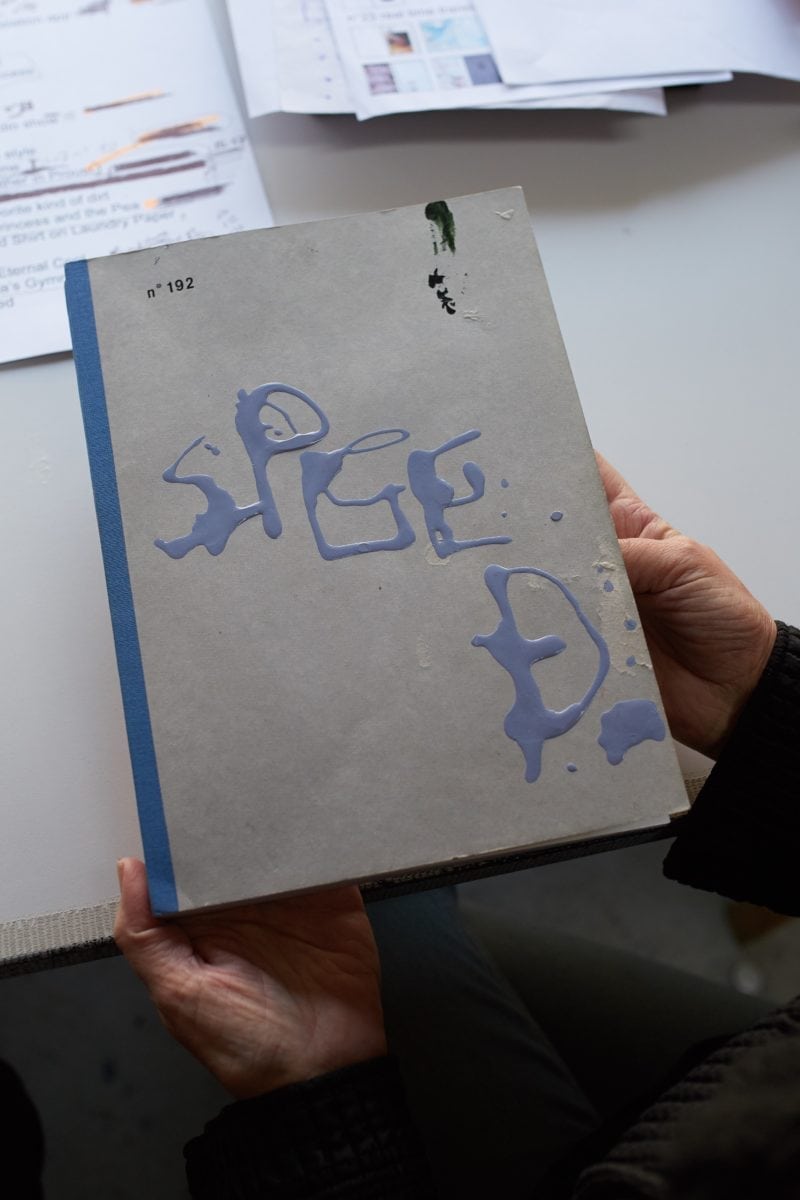

Yes, exactly. There are parts of my so-called bookmaking practice, that are unique and really precious to me. For example, once I went to one of my gallerists and told them they couldn’t sell them (my books), this was a conflict and he said to me “never come here again with works that are not for sale”. I’m working with contradictions here, I’m fully aware that art is meant to be sold, shown and circulated—which is also good and I do embrace this at times—but there is also a part in my work which is not interested in “art”, do you know what I mean?

I think it’s very apparent at the moment that—especially younger artists’—practices are becoming accelerated because they are told time and time again to produce something new and hopefully sellable. The art world is becoming closer to fashion as far as output goes; producing a new seasonal collection every few months.

I’m not immune, but it’s really important not to go into this mode. It can be so easy to exhaust your… I don’t want to use the word “creativity” as it’s so overdetermined, but you exhaust your sources and an inner world, or whatever you want to call it. That’s also why it’s so important to have these temporary places like Basso. It was important for all of us to have this non-career-oriented space, so one could produce, but not just for profit.

I am noticing the way you unpack space, you seem to have quite a ritualistic approach to seeing and working within it?

This is in a constant state of flux. For example, when I started working on the books it was because I didn’t have a studio, so they became my studio. They are all packed in individual cartons so at the beginning I could transport them on my bike. Also, if you look at my canvases, they are all exactly the size required to be able to fit through the studio door and down the fire escape. There is no other access to this spot, and quite often I have to carry them down myself to the art handlers because they are afraid of heights.

In this sense your environment and life determine the process rather than a ritual, I notice with the books you seem to have an archive list?

Each one is numbered. But I suffer from acalculia, which means I cannot process numbers very well. It used to be quite a problem in school; a good example is that I see three as half of eight, rather than looking at it like four is half of eight. One is also very similar to seven. I can’t do any mathematics, so when you see the numbers on the books they are not in a logical order. I try to make lists, but they always get out of order, or maybe I haven’t found the right system yet.

It looks like a set-list…

… and it changes all the time. Every book takes time and it’s really impossible to make a structure. I also never give them to someone else to just flick through, like one hands over a magazine, because there are some pages that are not for public consumption. I write every day, but I don’t want every viewer to see all of my work.

So you would have to be present for me to look at the book?

Yes.

You’re a gallerist’s worst nightmare.

I am (laughs). I have exhibited books several times in shows but I always bind certain areas because I am anti-participatory. I like it much more when you fix a window for the viewer.

It makes me think about the book, After Kathy Acker which as I understand Chris Kraus researched very heavily via Kathy Acker’s personal archive. In a way these books of yours are so personal, they tell the story of your life. How would you feel if someone rooted through them after you died?

Oh, that would be fantastic, I would love that. Kathy Acker has always been an important figure for me. When the first Blood and Guts in High School came out in Germany it had an awful cover, so kitschy, but I bought it anyway, devoured it and made my own cover for it. I did this to a lot of books I liked but hated the covers. But going back to the question, I often throw away a lot of my work or make a very strict selection of what to keep, as I like to be in the present, mostly. But thinking about it, I would really like someone else to make the cut and then I can be unreliable again.

All photography © Simon Kraus