So you have some new shows stateside coming up?

At the Drawing Centre—that will go through 4 February—and the show I’m having at Paul Kasmin Gallery will open on 18 January.

Since you’ve always addressed sexual politics in your work maybe we can start with what we are witnessing now with revelations over abuse in the art world. I wonder what you’re thinking about that? Is it comparable to anything you’ve seen before, and could what is happening with the media coverage be progressive?

This kind of harassment and rape and sexual abuse has been going on from the get-go, so I think it’s terrific that it’s coming out in the light and as a result it gives people in all fields strength to say “this happened to me”, use names and accuse people who’ve committed criminal acts, which sexual harassment is. It’s a great example for younger women. There are many times where people can’t speak out because of the fact that they will lose their jobs, and this gives them strength in numbers. It should have happened many millennia ago, but unfortunately, that’s not been the case.

“My take on feminism was observing guys and their behaviour, and nailing that in every sense of the word.”

Was it very different in the seventies and eighties? Attitudes have also changed, but were women speaking about it?

I would say pretty much every woman I’ve ever spoken to has been sexually harassed, it was just par for the course, so speaking out against this now is an extraordinary thing. Unfortunately, the United States has a president who doesn’t know this is unacceptable behaviour, which is a very sad comment.

Yeah, it’s retrograde, at the same time this is happening to have a president like Trump. You started out with the Vietnam war and the right-wing politics of that time. Now it’s almost come full circle, do you feel frustrated about that? Is there anything different about how you can react and respond to what’s happening now compared to the situation as it was then?

My work is autobiographical, and in the last fifty years it’s been the connection between the political and the sexual: the core of what I’m about. It’s about my rage at injustice. While I was a student at Yale in 1966 I started my anti-war Fuck Vietnam series, then soon after in 69 I started creating large charcoal screw drawings, which were an amalgamation of anti-war, sexuality and feminism. In 86 I made my first signature piece at Hillwood art museum. The signature was about male posturing, fame and my ego.

In 2010 I started my birth of the universe series, making a connection between the big bang, women’s rage and women at the centre of the universe. Right now I’m addressing the forty-fifth president.

My take on feminism was observing guys and their behaviour, and nailing that in every sense of the word, and I have continued with that. At this point, the world in a way has caught up with me, because it’s acceptable for women to have this kind of rage and put that out in a visual sense, and get exhibitions. Now when I make work, I can actually have it shown right now, which is a great luxury. With this Trump series I’m using a lot of Americana images that Trump is fucking around with. His idea of being an American is very restrictive and right wing. This is absolutely ludicrous because dissent is part of our past and our culture from the beginning.

Do you see that vision of America as quite a specifically male thing? Do you see all these things like war, the political situation now, as a direct result of the patriarchy?

I felt when I was doing these anti-war Fuck Vietnam pieces that it was definitely part of the patriarchy. It is nuanced, but I think on the whole there’s much more machoism in terms of war. I’ve used the phallus as a symbol of that. I made a piece in 68 called The Fun Gun, which is an anatomical drawing of a penis with a trigger and a cock.

With Trump we’re dealing with someone who is a fool, he’s a monster, a jester, a sexist, a racist. Donald Trump is a con artist, which is really what it comes down to. He’s using the White House as his own personal cash machine.

You’ve always worked with humour. With Cabinet of Horrors that humour is still very there, very direct.

I think it’s always important when you’re doing something political. My way of handling is with humour because it cuts the horror of it, but it also resonates much longer. Humour is almost like an ejaculation because you get it and you retain it. There’s something very positive about dealing with issues in this direct, outrageous, in-your-face way.

With that approach, you could be accused of being unsophisticated, is that a criticism you’ve had about your work?

Oh god, that is not true! I’m very sophisticated, but people make their own judgements when they see something, and that is their right.

When I was a student at Yale I read an article in the New York Times that said Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? was taken from bathroom graffiti, so I went in the bathrooms at Yale in 66, and saw the graffiti they had, and it was a big insight. Graffiti is more psychological than you can imagine. When someone is defecating on the toilet, their mind is free and going all over the place. I’ve used the graffiti as a metaphor.

At Yale, with the graduate students, there were three women in my class of twenty. Now, of course, those statistics have been reversed. When I came to New York, you were completely blocked from the system. So then there were women like myself who started A.I.R. gallery, and that was in 72. We were trying to come up with a name for the gallery and we went with A.I.R., Artists In Residence. I had suggested T.W.A.T., Twenty Women Artists Together. I didn’t take it as seriously as I would have now. Today it would be a great title for a gallery, but it was too ahead of its time.

I wanted to ask you about A.I.R. That was the first gallery of its kind, it’s still going. I also read that there was a period of twenty-five years where you didn’t have a solo show.

I had two shows at A.I.R. and eventually left. It was an extraordinary situation for the group of us because it allowed us to be part of the system that we were shut out from. We were taken seriously, we got reviews from the art magazines, we got a lot of kudos for starting our own gallery.

Even though you were part of some things like that, there were also years and years where the work wasn’t being understood or recognized, I wonder how you kept going?

I come from a very middle-class background, I was not privy to family money. I had four degrees, two from Yale and two from Penn State, and I taught part-time at universities in the New York area.

I was very lucky to have those jobs, but of course I did not have a one-person show for almost twenty-five years in New York, and that was extremely depressing. I kept doing a great deal of work regardless, but it’s very hard to keep doing without getting some kudos from the outside world, without selling or getting feedback. I think it’s best to be able to show as often as possible, in as many places as possible. But, there is a prejudice against showing work that is political, and I had the combination of being political and sexual, which is a real cockblocker, or cuntblocker, or whatever you want to say…

“There’s something very positive about dealing with issues in this direct, outrageous, in-your-face way.”

I was included in some big feminist shows and was part of a lot of feminist groups, like Fight Censorship with Anita Steckel, Louise Bourgeois and others. I was also part of the Guerilla Girls for a while. These things kept me going. Having groups of women who were supportive of my work was extremely helpful. I had support from men too, like William Copley and Walter De Maria. I had support from people who treated my work and what I was saying very seriously, so it was enough for me at the time. It was great to be in New York when you’re young and you think anything is possible. I had an enormous amount of energy, which I still have even at a much older age. I am thrilled that at this point there has been so much validation in terms of me and my work.

A few women spoke about it at the panel at Frieze for Sex Works, about the U-shaped career that women often experience. When they’re young people are really interested in them but treat them superficially, and when they get older, it’s like “how cute, here’s Judith with her giant drawing of a cock”, and there’s an edginess to it. How do you feel about that, do you feel that people are latching on now because it’s trendy again?

I’m very happy to show now and I don’t have resentment of the past. I think it’s fully about the Sex Works show. The title is great, because it gets a lot of interest, in the centre of Frieze. In the past I wasn’t embraced by a lot of feminists because my work was not self-referential. They said that if you’re doing a drawing of a penis it can’t be feminist, which is not the case. Men have the organ, but anyone can use the image and do what they want with it.

It’s interesting that many of the artists who were in Sex Works also had this problem within the feminist movement. I was speaking to Renate Bertlmann and she said the main change since the seventies is women’s reactions to her work, that there are different interpretations of feminism as well.

That’s correct. I felt, with a Jackson Pollock painting, the psychological underpinnings of that painting is my screw drawing, the ejaculation. My work is crude, but it’s not obscene. It’s not sexually arousing, it’s done for a political reason.

Can you tell me more about the new works?

The black and white charcoal word pieces, Nixon First National Dick, and all the pieces that are Trumpenschlong, Money Shot and All American Spread Eagle—all these are at The Drawing Centre. But at the Paul Kasmin show they’re all paintings on canvas. It will be completely fluorescent, in black light. They’ll come right off the wall, because of the fluorescent colours. We’ll create a surreal, parallel universe, and it’ll be as unreal as his presidency has been.

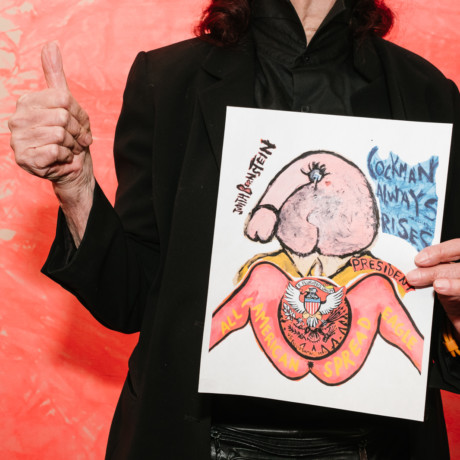

You know, your magazine is called Elephant, it’s funny because I used this cock face—and I made this image in 1966 when I was a student at Yale, it was against a reactionary governor of Alabama, George Wallace. It was called Cock Man Always Rises, and now I’ve taken this piece and made it as a portrait of Donald Trump. But this goes beyond Donald Trump, it’s about machoism. But I’m saying this because the phallus is the nose in the cock face, and it looks like an elephant!

Now that would make quite the cover!

Photography © Donald Stahl