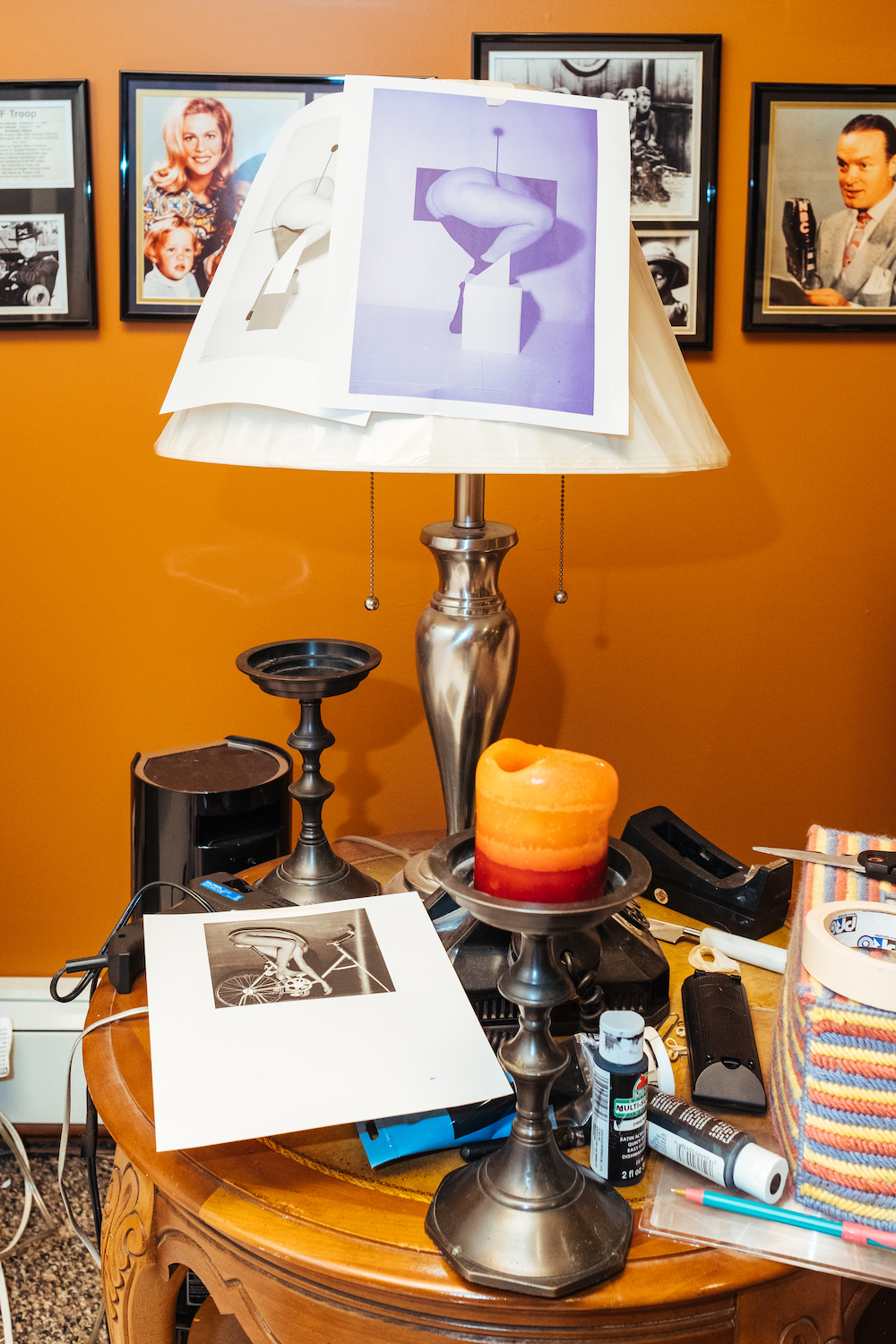

To call Patricia Voulgaris just a photographer would be incorrect. Her process begins somewhere in the middle of sculpture and performance, as she erects ephemeral tableaux out of cheap objects—torn paper, foam core, broken furniture—and her own body, then photographs the resulting composition. She works in the attic of her childhood home, an original Levitt house an the archetypal suburb on Long Island. In addition to the lights, prints and handmade props that she uses for her work, the space is filled with old tchotchkes and family paraphernalia: movie posters, pictures of dead relatives, CDs and DVDs collecting dust. A black and white photo of the village people—signed by each village person—adorns the wall. A threadbare pillow Patricia made in grade school lays underneath a stack of freshly-framed prints. A new show of Voulgaris’s work, titled Nothing Can Stop, opens on 3 February at the Rubber Factory in New York.

Let’s talk about the photographs in your new show. They’re part of a larger body of work you’ve been making for four or five years now. How did they come about?

It started when I graduated from the School of Visual Arts in 2013. I was considering how I might be able to incorporate the ideas I was thinking about then—home, memory, family, things like that—into a new body of work. I literally woke up one morning and the first image that came to my mind was the picture with the braid (Braid, 2013). That image really means a lot to me, because that was the first concrete idea that came to me for that series, called Fragments. It was a turning point in the trajectory of my work.

What’s the role of paper in your work? You’ve described paper before as being a living thing, analogous to your person in the pictures. I had never thought about it like that.

That started around the same time, with that first picture. I was in school and I didn’t have a lot of money. So I was like “What can I use that I have access to? Let’s try this paper.” I use props to elevate and transform the body. Perspectives become distorted, shapes and fragments of the human body are integrated into complicated compositions that blur the line between space, object and material. Paper, being accessible and easy to use and bend, lends itself to that. It became my go-to prop. It allowed me to transform the body into something more, into something that I was looking for.

“The props are important to me because they are an extension of my body. I’m physically in the sculpture, alongside them.”

You mentioned that you’ve chosen to include some of the props alongside the photos in the show at Rubber Factory. What’s behind that decision?

The props are important to me because they are an extension of my body. I’m physically in the sculpture, alongside them; in that democratized space, everything is equally essential. I have a history with them. When making the work, you spend time with them, you photograph them and you’re constantly going back, staring at the result, editing it. I’m never concerned with whether or not the props are going to make sense. A lot of them have been sitting in this attic for God knows how many years. I’ve lived with them. And in the gallery when you pair them with the photographs in which they were used, it becomes a conversation between the two.

I like the choice to include the props because it shows just how intuitive and laborious the process behind the picture is. I’m interested in how I can use the space in a gallery as a way of mimicking everything that happens in my studio. This is so much of what my process is about—just being in this limited space and learning to use the tools around me to create something compelling.

In your work from a few years ago, such as the Fragments and Hidden in Plain Sight series, your body was more concealed in the pictures, more disjointed. With these newer pictures, on the other hand, your body has become more integral to the composition. It’s also more exposed. What is behind that development?

I think that if I let myself open up a little more, and be more comfortable with my body, I can make something emotionally resonant. I feel a lot of pressure to hide. Especially being a woman—there’s an ongoing conflict between what you show and what you don’t show. With this exhibition I’m trying to let it go and just be like “Yeah, I’m going to put my ass in the window and I’m going to be okay with it.” I feel like the more you allow yourself to put things out there and not hide behind things, the more people appreciate you for it. They see that in your work and that makes them want to invest themselves in it. They feel very comfortable with you knowing that you’re comfortable with yourself.

“The more you allow yourself to put things out there and not hide behind things, the more people appreciate you for it.”

I’ve heard you talk a great deal about memory before, how it’s related to the fragmentation in your work, but also how memory is so intertwined in our relationship to photographs in general. How are those ideas of memory embodied in this newer set of works?

A lot of it has to do with childhood memories, memories of people that I don’t keep in contact with anymore. Pieces of people, objects that I’ve always kept with me—I want to reflect on these memories and transform them into space. For me it’s an exercise in paying attention and focusing on what you’re looking at and being more attuned to the things that make up your life. I’ve found that people tend to connect with them in their own personal ways too. When one considers the past, their memory of a certain person or place is often fragmental, however, one can remember certain distinct qualities about an individual or a particular place. Time passes, recollections fade and become broken down into simple forms, shapes and patterns. These forms are what hold memories together.

Your process is fascinating and invites curiosity. There’s something about the visual language of the photographs and the logic of their composition—looking at them, you just want to know how they were made.

There’s a lot that goes into it. Some of these images take months to make. Others take a couple of days. It’s intuitive; it’s a matter of getting it to a place that just feels right. You don’t know how the object is going to look next to me, or how it’s going to interact with my body. There are a lot of little variables.

Photograpahs © Don Stahl

PATRICIA VOULGARIS, NOTHING CAN STOP

February 3 – March 7, 2018 at Rubber Factory, New York