Elephant speaks to Shamiran Istifan, Marisa Kriangwiwat Holmes and Tasneem Sarkez: the artists exhibited in Rose Easton’s current show ‘Saccharine Symbols’. A sugary display of roses, cupids and rabbits betray their cloying exterior symbolising socio-political narratives and personal histories. The aftertaste is anything but sweet.

Rosie Fitter: The use of banal, familial objects, used by Shamiran and Tasneem, as well as the vernacular, commonplace images shown in Marisa’s inclusion of advertising photos, demonstrates the wide spectrum of influences drawn upon in your art. What do you aim to explore or portray with these rhizomatic, ciphered symbols, do you think this creates a relational, intimate aesthetic experience with the viewer?

Marisa Kriangwiwat Holmes: I’m really interested in post-internet photography. I like to consider the idea of online images as a language that we use and interact with every day through our phones and computers. I never really loved cinematic photography; I know that all photography has its roots in it, but I feel more aligned with the generation that connects with advertising and photography as a language we can all read, sometimes without even realising it has almost become a slang. I used to work at a race track which somehow led me to take a lot of photographs of horses and other animals. When I started reenacting eBay sales, I began taking a lot of photos of animal figurines. Initially, this started as a kitschy idea of ownership—a way to have a sense of control over your pet dog—but it also relates to an animal’s presence on the internet, how popular that is, and how attractive it is to people.

Shamiran Istifan: I tend to shift my artistic approach often, from exploring familial artefacts to a contemporary engagement with symbols representing the present and future. My work involves archiving objects and stories in my own way, incorporating shapes and forms that carry coded layers, as seen in Broken Doll, Fol-De-Rol (2023) or the sword motif, both in the current show at Rose Easton. Starting with domestic symbols, I love to construct a geo-cultural map intertwining personal and societal narratives. My focus is on connecting and abstracting visuals and context, employing symbolism to represent the physical body and spaces. Using indoor settings as a reflective lens, I contemplate broader societal themes. And oftentimes, I really tend to approach the world in a cartoonish way. Memories, to me, are a mosaic of shapes, feelings, visuals, and geometrical connections.

Tasneem Sarkez: I definitely begin with a more familial and personal archive, and then consider the context of modernity and objects that feel very present around me. I contemplate the symbolism, especially in the context of these two paintings. They’re both decals, illustrating the idea of overlay—a gesture of adornment. Such is shown in the way ’11:11′ is imposed on the doors of 11:11 (2023), and the roses on the tire cover of Good Morning (2023). I appreciate symbols, particularly because the modification of the object through its symbols is where identity takes place. It goes beyond being about the object’s materiality; there’s almost a personhood to it, a personification. I think we use symbols a lot for that reason, to proclaim a sense of identity. Approaching the idea of the modern identity of Arabness with this same act of adorning or declaring— is what it is to be an Arab woman or an Arab person in the diaspora. There is a lot to say of using symbols as pride and armour. I hope that people can see themselves in these environments I’m creating, and through using these symbols—especially in Chessboard (2022) —I aim to help the viewer register their place through the relation within those symbols.

RF: I’m interested in how each of you builds your collection of symbols. Tasneem, you’ve mentioned exploring your identity through collecting and archiving material, leading to your translational abstraction of Arabness. Shamiran, you’ve engaged with various forms of archiving, including personal photography and familial references. Marisa, you incorporate advertising imagery, posters, and documents into your work. Given that we’re constantly perceived and positioned by others, how has this process enabled you to explore and construct your own perception and placement of identity in your work?

TS: There’s a sense of ‘pastness’ imposed on many marginalised identities, where existence is constrained by historical labels. Arab culture, in particular, is often seen as a singular identity, limited by Western characterizations in the media. To modernise an archive, you have to consider ideas of futurity, thinking about the tense of its existence in its most present form. The concept of your future isn’t granted by the external world and its perceptions, when your identity is in opposition to the status quo. So I ask myself to actualize the future of my identity in the work that I make, by making work I want to see in the world right now – to then place myself in it. The archive, in my view, is an active process of registering what you observe in your environment. For instance, the cars depicted in my paintings are inspired by those I encounter in everyday life. The use of ‘Good Morning’ in this painting is drawn from the WhatsApp memes my family sends me. It’s about being attuned to how you perceive your identity in the everyday while understanding its history. Collecting an archive requires an acknowledgment of its historical precedence, creating an active relationship with elements from both the past and present to construct how you want others to perceive you.

SI: In the ever-changing tapestry of my process, I find inspiration from both the past and the present as they continually influence and shape one another. Understanding history is essential for me to navigate through narratives and contradictions, especially as a descendant of genocide survivors. But while paying homage to elements rooted in the past, I‘m gradually incorporating elements of both the present and future. My choice of medium varies by project, where stories and symbols serve as fluid placeholders within a broader network. Each reference intentionally connects to another, creating an interplay between experiences and social contexts. This approach allows personal narratives to acquire nuanced dimensions with my own codes hinting at structures, numerical systems, unwritten laws of society, among other things. My work intertwines familial narratives and traditions into the broader picture, creating a bridge between personal experiences and collective influences.

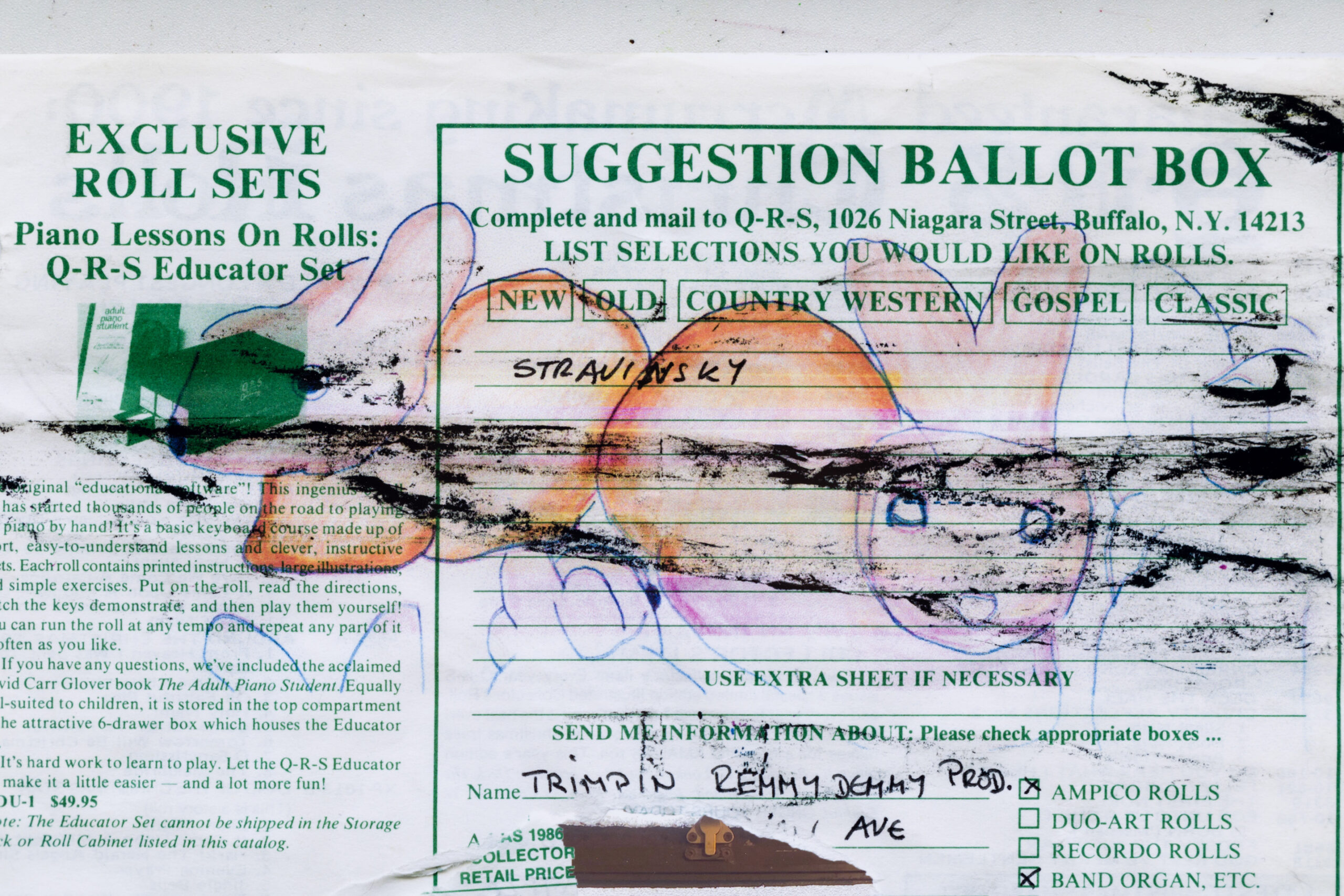

MKH: This series isn’t about a specific history of mine, but there’s always a presence of Hong Kong in my work. Recently, I’ve chosen collage as a medium to address issues in a non-linear, anti-narrative manner—creating a plane packed with many images. I hope this provides space for the viewer to have various beginnings and starting points. In terms of an archive, many of the pictures I use are ones I took when I was 16 and still living in Hong Kong. Nowadays, I sometimes struggle to take photos, to claim just ownership of them, and even to have the confidence to present them plainly and in isolation. Photos are now heavily influenced by the way we share them on online platforms; even on social media, it’s a continuous cycle of screenshots saved, perhaps with an echo of a tag. I’m trying to pay attention and respond to the composition of this language by sharing something. Understanding how photos are viewed today, we can’t simply look at a singular image anymore. We can’t just look at a plain photo; we have to see text over it, directing us somewhere. We’re developing an affection for that aesthetic.

RF: The duality of a soft, saccharine, and appealing aesthetic set against a real and politically charged narrative is a recurring theme in your works. The kitsch aspects also conceal a variety of meanings – Tasneem, you’ve mentioned exploring the concept of Arab kitsch. What motivates you to employ these aesthetics, and why is it important to your work?

SI: I have a real fascination in strategic masquerades, such as the mythology of sirens with their captivating allure while concealing deeper, sharper facets beneath the surface – I think this is especially prevalent too in relation to class and access references. The language of symbols helps me navigate through the fluidity of identity and society, and the aesthetics of my political creations embody a certain vulnerability. For example, my approach oscillates from lighthearted to tragic and back, in works like the aforementioned ‘Broken Doll‘; composed of makeup and latex, featuring both flesh and inner pink, and incorporating wadding. Another focus of my work is examining the perception of isolated women who exist within a subtle dialogue between desire and danger. I explore the intricate power dynamics inherent in such narratives. When contemplating broader power structures, I often associate with Hegel’s Master-slave dialectic.

TS: Especially in the way we perceive kitsch, it’s a universal concept with its own cultural specificities, that is both political and humorous. There is a recognizability to memes and the readability of how images exist—centred text and saturated elements. Kitsch has a universal framework, an alluring quality. Across all cultures, there’s humour and sweetness in these kitsch objects. On the flip side, in the mass production of these objects, a pattern develops, associating them with a particular culture. Depending on how that might be perceived elsewhere, it could be seen in opposition. I’ve noticed these patterns growing up, even just going to the halal market, where there is a rose on every packaging and roses have such a commercial but symbolic significance worldwide. It’s interesting to see the rose as a symbol on something like a beat-up car, because it’s a paradox. There’s an emotional mediation to the element of kitsch in my work, perhaps due to the tradition of using oil on canvas. Formally, there’s a romantic gesture and haze to how I paint, mediating and layering kitsch beyond its initial presentation as sweet and funny. The visual semiotics of Arabness becomes something to sit with, rather than go unnoticed.

MKH: To add to that, what I find wonderful about kitsch is how it operates in pop culture and how easily it can be communicated to the masses. There’s a certain aspect of it that I want to set free and just let it be interpreted. There’s something amusing about playing within that cliche. When I use tropes like bunnies or something childish from a children’s book, there’s a desire to be read and to break away from feeling art institutionalised. I have a desire to find an anti-capitalist route, delving into kitsch or popular culture because I want to reach broader audiences. My topics extend beyond just diving into art history, which many important artists do out of necessity.

SI: Sometimes the humorous view or the pop culture appropriation of kitsch is a classist move. Kitsch is so often about class, and it’s a charged word. I’m trying not to use it anymore because I’ve seen how it’s perceived by a certain educational class, merely as a tool of entertainment, not considering it as an actual experience. It feels charged by certain groups, especially in the West, as something entertaining or as a transient part of pop culture that can have a moment and then be over.

Considering Donna Haraway’s concept of ‘Speculative Fabulation,’ the idea of using storytelling practices to imagine worlds radically different from the one we know and how each of you weaves stories and narratives into your art. How does incorporating oral mythology and personal histories contribute to the layers of meaning in your work, especially in terms of storytelling as a means of preserving cultural narratives, shaping collective identity, and drawing attention to experiences that are often overlooked? How does this feed into your incorporation of themes such as sentimentality and nostalgia?

SI: Motivated by politicised experiences, I aspire to create and imagine spaces in my art that transcend the reality of the physical world. A central goal of my artistic work is to shed light on stories that often otherwise remain ignored or unseen, given the predominantly oral nature of my cultural background, while still keeping it coded in my own language of shape and material. The vinyl symbols on windows of ‘Saccharine Symbols’ are Mesopotamian cuneiform, the earliest forms of writing, referring to a heritage that is very deep and very rich but full of loss at the same time. The inspiration for incorporation of car elements comes from the oil and gas industry referring to wars and territories but also the representation of female figures for male entertainment: a decoration for a car, the representation of a man‘s status, another definition of ‘territory’.

MKH: Constructing a narrative for me stemmed from a place of seeking a specific direction after graduation. I emerged from a rut and began using photos of animals and animal objects, eventually delving into digital collage and lens-based media. I thought it was interesting that contemporary documentaries incorporate and stitch together various types of media in one video—shifting from red camera footage to iPhone clips for example. I thought photography could be considered similarly, incorporating different formats in one plane, from a low resolution jpeg cut against scanned 35mm. Today, people can digest this mix, this incongruence, thanks to social media making it palatable. I wanted to include specific personal histories in a sentimental way, also focusing on the political history of Hong Kong. Thus, I aimed to make my work immediately sensuous, offering two ways for the viewer to enter the world, and if they wanted to research something further they could later. Leaving my undergrad, I was accustomed to creating overly didactic photo work and struggled to feel it was reaching people.

TS: Narratives are a focal point in my work, driven by a personal and collective approach that engages with historical and contemporary issues. The through line in my work revolves around language, exploring the sentimentality of symbols—delving into the poetics and enduring meanings of phrases throughout time. This experience of time is granted differently to those with marginalised identities or alternative histories, bringing a sense of longevity and depth to their narratives. The language associated with the power and industry of cars is inherently patriarchal, and it’s intriguing to observe how that narrative shifts when adorned with a rose and Arabic script. Considering Arabness in its modernity, often viewed with hostility, juxtaposed against a message like ‘good morning’ and a rose, challenges expectations of how Arab people should present themselves as a culture. Exploring these paradoxes of culture is essential to me. There’s a reciprocity in these ideas, echoed in Phillipa Snow’s text about Snow White biting the apple—sweet yet poisonous. Even when contemplating post-internet images, there’s a nostalgia and sentimentality that’s honourable, yet simultaneously evokes laughter. Arabic poetry heavily influences me, and in any language, certain parts resist translation, creating a gap in understanding histories that draws us to both sit with nostalgia and question how we can represent it. There’s a privacy and personal legibility in this, providing a comforting aspect in the complexity and depth of cultural narratives.

What are your thoughts on the potential to repurpose technologies for positive political ends with emancipatory, freeing potential? The ‘Xenofeminism and a Politics for Alienation’ suggests using technological alienation as a means to generate new worlds. Do you see your work aligning with this call to action, contributing to the creation of new narratives or perspectives through the lens of technology?

TS: Images function as social tokens and cultural signifiers, extending beyond visual qualities. They carry significant meaning, especially within the internet, with layers of sharing through screenshots, compositing texts, photoshopping—it goes on. The quick consumption and interpretation of images, require various elements for recognition, even across different languages. The global internet experience varies across cultures, and in the art world, artists are breaking away from these norms, finding emancipatory qualities in deconstructing and reconstructing them within the context of art. The embrace of Arab aesthetics doesn’t grant you safety, not that I want to make my work palatable, but it’s important to recognize how easily images of representation become politicised against you. In using technology I’m interested in how these politicised aesthetics can be combined with more visual, romantic, and poetic forms. In using the language of the internet and its framework for understanding images, these narratives become accessible for everyone to see, read, and interact with, rather than dismissed.

MKH: As artists, everything we absorb can find its way back to our studio practice in a homogenised manner. Moving to New York, where conversations about painting are abundant, I attended a talk by a photographer who expressed interest in what the younger generation is producing on the internet. This made me contemplate working with a medium oversaturated in people’s lives. Sometimes, I feel it’s an attempt to appear painterly, abstract yet maintaining ultra-recognizable subject matter. People don’t want to disconnect from the world; they seek information at the same rate, maybe just needing more assistance. I believe in the political meme, recognizing political actions as aesthetic and capable of being aestheticized. They help people delve deeper and move them, influencing the way art looks, even in the realm of digital images within painting.

Considering your interest in headlines, the semiotics of political language, and the exploration of digital depression—amidst this media onslaught, how do you navigate the digital landscape and the intersection of the personal and political in your practice?

MKH: I find a connection between the role of a musician in my art practice. Many musicians now record digitally due to the affordability of technologies that allow for DIY recording in bedrooms. Recording practitioners showcase impressive skills, often avoiding traditional studios and opting for extended periods of layering in a manner similar to Photoshop. After achieving a crisp, digital sound, they run it through a tape machine for a gritty effect, reminiscent of a cheaper sound from a decade ago. Similar transformations are happening in the realm of images, which is why I desaturate my work. Urgent messages, like those concerning Hong Kong responding to national security laws, find a feasible outlet through art, allowing for abstract expression without the risk of censorship. I achieve this with slightly blurry, desaturated images that are easier on the eye and digestion, yet still carry significant meaning. These images remain legible for repeated interpretation.

Tasneem, you’ve expressed your love for the word ‘Apricity,’ describing the warmth of the sun in winter; Sharmiran, you’ve talked about constructing the idea of ‘freedom visualisation’ in your work; and Marisa, you mentioned the need for our eyes to rest from saturated imagery amid overwhelming online content. Do you believe your work provides emotional and psychological refuge or warmth? How do you individually create respite, safe spaces, and sanctuary within your art for both yourselves as artists and your audience?

SI: My exploration in my work through symbols is often in response to the sense of reduction associated with existing in a political body and owning a mind that has to proactively unlearn things in order to own autonomy. But realistically speaking, I know that the art I make exists in an institutional art world context that is upholding the same old system of power while just changing the facade. Still, I love to create my own alternative reality, my own simulation in our existing simulation and it can be through art or any other form of expression.

TS: I would say that I find refuge in my work through a sense of cultural materiality and how I manipulate it to represent what I want. Apricity, the warmth in the cold, is about holding space for an identity that might not often be seen.

Words by Rosie Fitter. Images courtesy the artists and Rose Easton, London. Photography by Jack Elliot Edwards.