My first memory of seeing an erotically charged image was on my brother’s portable PlayStation, circa mid-2000s. My brother and his friends were laughing at a fully naked picture of David Beckham, arms extended and legs crossed in a crucifixion-like fashion tableau. The combination of Beckham’s performance as a martyr with his slender and tattooed body, and his flaccid yet simultaneously engorged dick, conjured in me an early feeling of gay desire that remains palpable to this day. This anecdote locates what may have been the beginning of my experience in developing a personal visual narrative of queer eroticism, one that is entirely subjective and focused almost exclusively on male bodies.

Just a few pages into Barbara Hammer’s recently published book, Truant: Photographs 1970 – 1979, I am confronted with a different journey towards building a queer visual eroticism. In a short introductory essay that beautifully pairs detailed descriptions of photographs with a chronology of Hammer’s practice, writer Andrew Durbin

points out that the artist’s fascination with the female subject also began with her fixation over one particular image: that of a female model on a motorcycle during a live painting class.

“Hammer moves past representation to appropriate and become that which she desires the most”

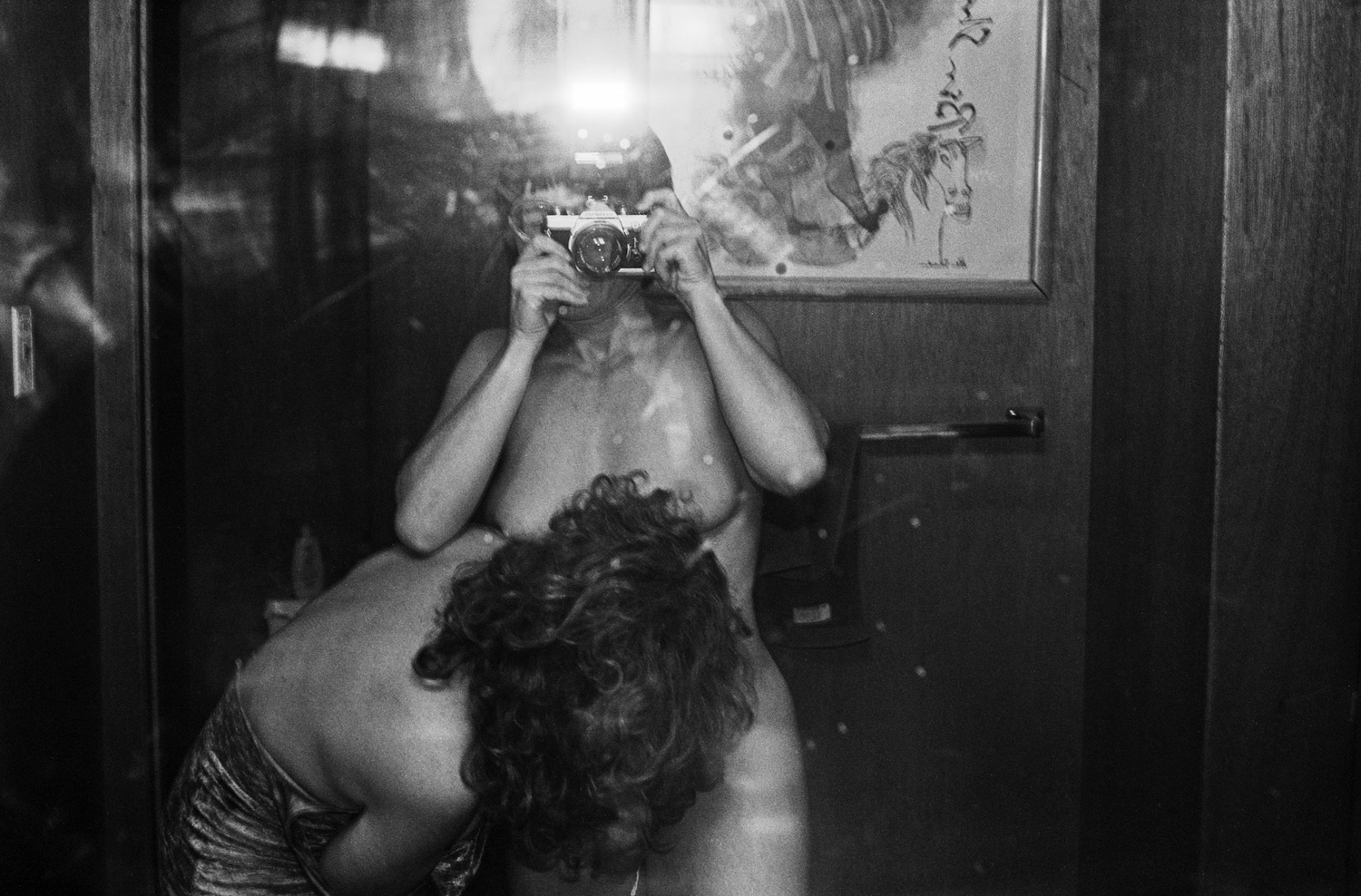

This character would later be embodied by Hammer herself in many of her photographs and films, some of which were taken during trips in the early seventies to West Africa and Germany with her first ever girlfriend, Marie. In these self-made moments, Hammer moves past representation to appropriate and become that which she desires the most. The resulting collection of photographs in this book, released last year by New York-based independent publisher Capricious, documents this early and prolific period in Hammer’s film and photography practice. In itself, it also represents the beginning of the artist’s coming out as a lesbian woman.

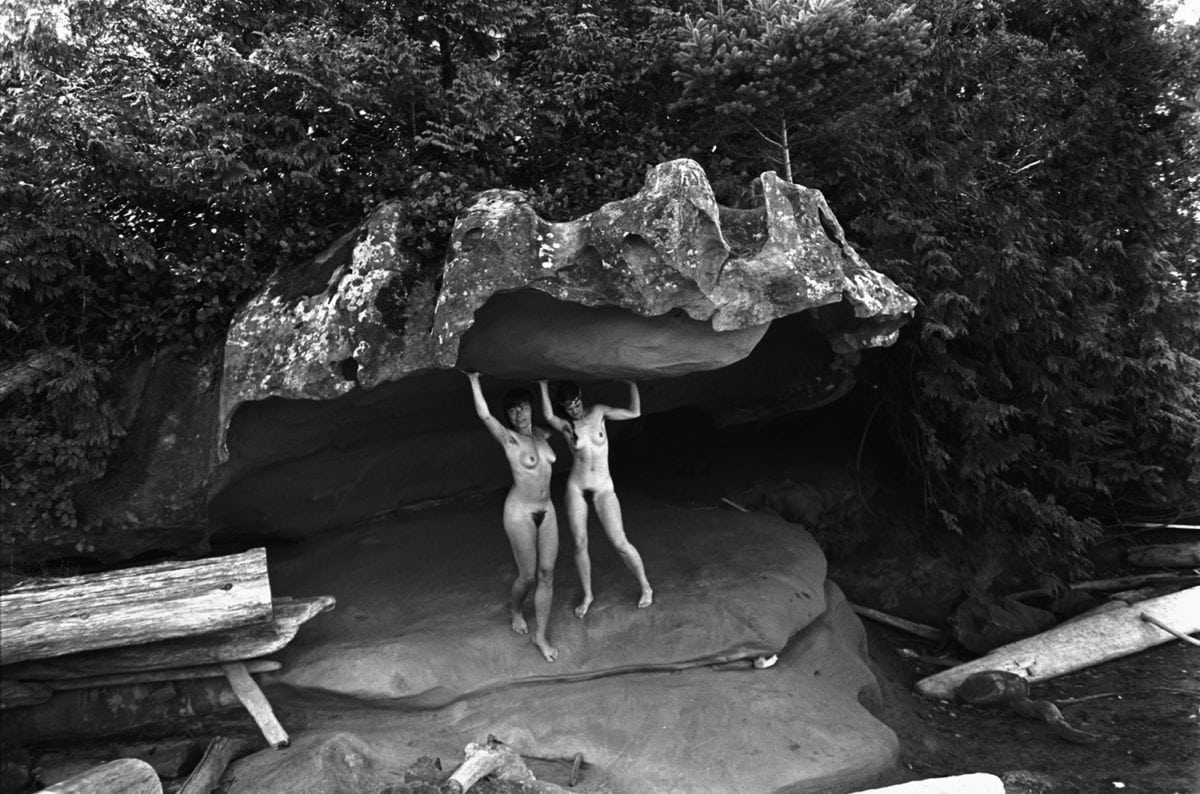

Featuring a generous array of images from the early to late seventies, the photographs in this book heavily contrast with the type of work that Hammer is mostly renowned for. Her work in experimental cinema began with the production of short films, mostly in colour, and shot on a Super 8mm motor-driven camera with a zoom lens. Hammer’s initial experiments with the medium included painting directly onto film, using expired reels, and toying with double-exposure, tools that would become vernacular to her practice. Films such as Multiple Orgasm (1976)

—for which the artist layered images of a moaning woman and close-up shots of a pussy being fingered with holes, cavities and empty spaces within mountains, rocks and caves– illustrate her seminal and provocative style.

Although also at times explicit in content, the photographs displayed in this book could not be, for the most part, formally further away from the multi-coloured, multi-layered, orgasmic frames of Hammer’s films. Here sharp black and white images in single-page compositions are presented both paired and alone. While the artist’s early films are busy and messy for all purpose and effect, these photographs are more akin to a straight documentary practice. As if to acknowledge this disparity, the publication also features a series of inserts of full page-size images printed on thin tracing paper in purple and orange colours.

The pages replicate the effect of Hammer’s signature use of double-exposure, with the images here bleeding into one another. One of these inserts focuses on images from Hammer’s film Double Strength (1978)

, where aerial dance pioneer Terry Sendgraff—one of Hammer’s lovers—performs a trapeze-like choreography, flying on and off from swings hanging from the ceiling. While the film itself doesn’t feature many scenes with double exposure, this section uses photographic documentation to re-imagine the film’s content and recreate the kind of sensual layering that made Hammer’s work so visually evocative.

“The participation of these women in many of Hammer’s films—often as collaborators—reveals a desire to be made visible, even if not fully knowable”

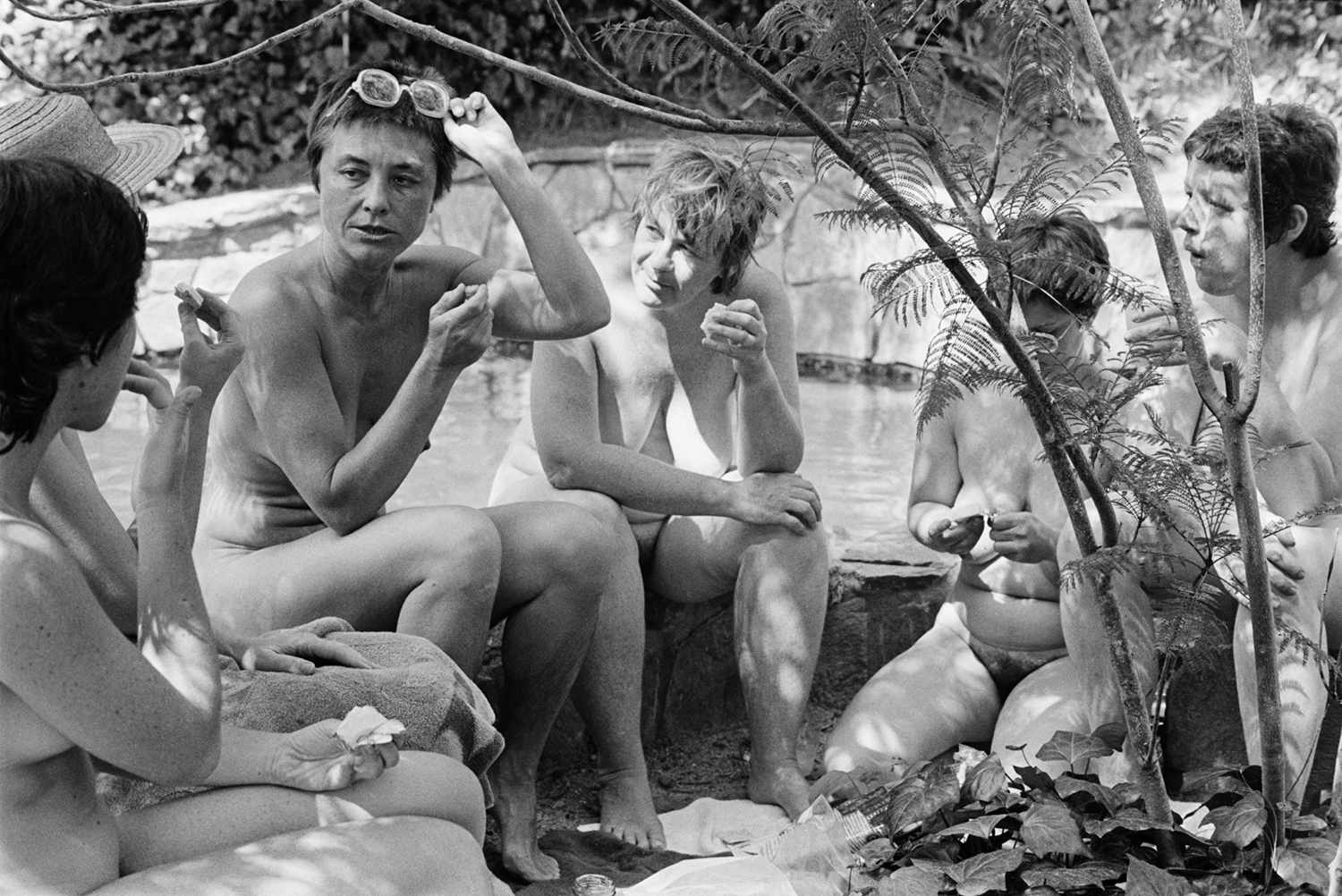

In these spreads we see Hammer, her friends and lovers in both private and public settings, indoors and outdoors, but the presence and use of the camera throughout suggests a willingness to submit and expose oneself to an other’s gaze. The participation of these women in many of Hammer’s films—often as collaborators—reveals a desire to be made visible, even if not fully knowable, within the control afforded by the frame of the lens. Whether depicting intimate moments of embrace and care, explicit scenes of sex and lust or just everyday experiences of being together, Hammer creates a political representation of female sexuality within both her films and photograph. Her practice is political in that it is uncensored, intergenerational, body affirmative and of the everyday.

The images themselves constitute a sort of proof of the kind of profound companionship that might have been experienced by these women within their prescribed situation of female-to-female fellowship. Moved from the privacy of the archive onto an object of easy distribution and display, this book grants us permission to enter these now, in time, distant experiences. The gesture is similar to flicking through someone else’s intimate family album; occasionally, it may be inevitable to feel like something of a stranger looking in. This distance however does not take away from an ability to connect with the material, or to be affected by it. Truant is an invaluable contribution to queer and art history; a tangible source of nourishment and inspiration.

“Hammer’s practice is political in that it is uncensored, intergenerational, body affirmative and of the everyday”

Thinking of images and strangers more broadly, the fact that we are exposed to depictions of fully naked women on TV, film and newsstands much more often than men says a lot about the types of bodies that society deems to be seen and consumed versus those that are meant to be doing the looking and, putting it crudely, “the eating”. The prolific sexual representation of women has a convoluted history that extends to all visual mediums, from art, to commercial photography, advertising and film. Dealing specifically with the male gaze, the title of novelist Siri Hustvedt’s 2016 book of essays formulates, in itself, an interesting combative proposal: A Woman Looking at Men Looking at Women. Hustvedt’s play on words and perception calls to reclaim the act of being looked at by looking back.

With Truant, and in her practice more broadly, Hammer enacts a similar will to subversion. Instead of looking back, she removes male sexual pleasure altogether, creating complex and honest depictions of unrestricted female sexuality that are of, and between, women. By capturing herself and other female bodies as both the content and subject of their mutual desire, Hammer creates a specific picture of female sexuality that places love, care and intimacy at the intersection with sex, body and nature. At stake here is a process of redistributing depictions of women that provide other kinds of representations of their own sexuality, as well as of the liberating freedom and joy that can be found in radical queer desire.

All images courtesy of the artist, Capricious, and Company Gallery, New York