© Jeff Mermelstein

On my way to work this week I tried to look around me as I imagined a street photographer might do. On my lap was a copy of Bystander: A History of Street Photography. (It’s heavy. I forgot it was on my lap when I stood up, and it slapped hard against the floor making a noise loud enough to send a ripple of mussitations down the carriage.)

Who would I photograph, in that self-consciously urban style that we think of when we think of street photography? Where were the gritty, pock-holed faces, the weathered and wise, the savvy-beyond-their-years kids, dirty fingernails and tattered coats? Could I find any moments in the squashed, over-heated faces of the commuters wedged in around me, some kind of soaring human empathy or resilience—an expression that could be a microcosm of British society? I gave up and put my eyes back into my book.

Courtesy George Eastman House

Perhaps I have the wrong approach for street photography. It comes, after all, from the belly not the brain. It’s an instinct and an impulse. Street photographers are often likened to perverts, lusty prowlers. They talk about an urge—or a compulsion. They snap indiscriminately and obsessively. They get up in people’s faces. “The street is like a nerve ending,” as photographer Bruce Davidson puts it, in Cheryl Dunn’s film on New York’s street photography of the last half of the twentieth century, Everybody Street.

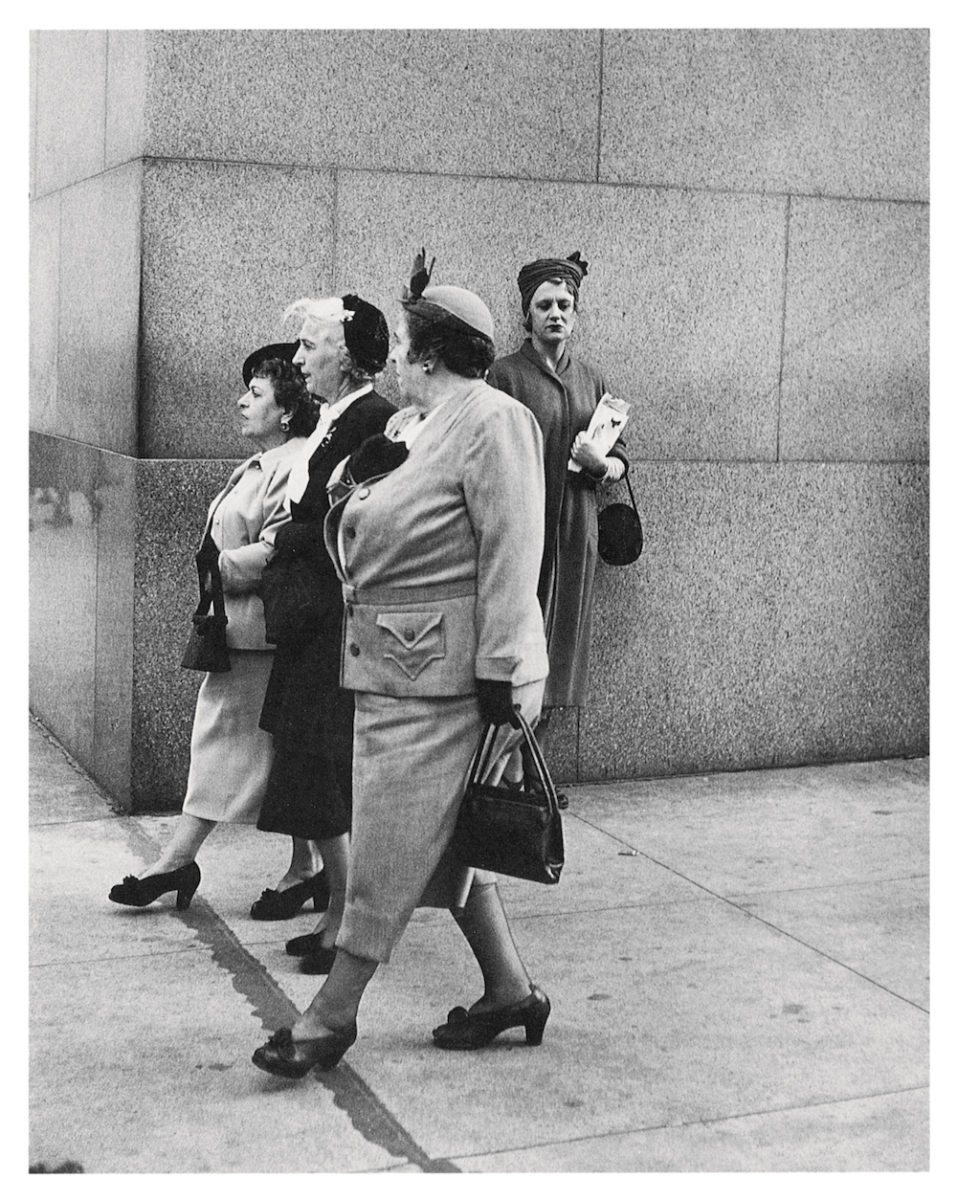

- (Left) Dan Weiner, Fifty-Seventh Street, NewYork, 1950

© Dan Weiner, courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery - (Right) Richard Bram, Domincan Day Parade, 6th Ave, New York, 2005

© Richard Bram

Bystander, redesigned by Atlas, reissued and released this month, not only has the weight of an Encyclopedia but the comprehensiveness of one too. Starting in the nineteenth century, it reminds us, looking back, that the way people inhabit the streets is constantly changing—pedestrians were once the main vehicles passing up down them, and the street was a communal area, where all strata of society came together and thrived. Later, it was addled by war, then drugs and danger. The street became more threatening, a place for the disenfranchised. The way we animate the streets changes too: in the fifties, it was the elegant stride, in the seventies, the standing smoking pose, and in the nineties, the nonchalant swagger. Nowadays, it’s the downward-facing smartphone shuffle.

Courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery, New York © Doug Rickard

But it’s not only people who define the street. One of the most intriguing things, looking at Bystander now, is the shifting definition of what a street is, through the eyes of these people who observe them so closely and anxiously: from the earliest exponents of the genre, who mostly shied away from people (Atget, Stieglitz) and stuck to the surreal and the spectral, or else made people small, gobbled up by the industrious machine, by the smogginess of New York or Italy’s impoverished South (favourite locations for the genre), where the street is politicized. While street photography has been synonymous with Paris, New York, Naples and London, a thoroughfare in rural Bengal, a desolate desert path in Cairo, or the chaotic route through Crawford Market in Mumbai, are also streets. A street does not have to be paved, with either cobbles or human footsteps.

As Bystander emphasizes (punctuated by conversations that have continued over thirty years between the book’s editors) in our fast-paced, digital, globalized era, the democratic nature of street photography isn’t lost, even though they suggest the genre’s importance has been sidelined more recently. “Street photography is so essential to photography per se that the existence of photography as a medium is unimaginable without it,” writes Westerbeck, wistfully. “For me, it is the very heart and soul of what photography is.“

Courtesy Gernsheim Collection, Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, The University of Texas at Austin

Bystander

You can buy a copy now at elephant.art