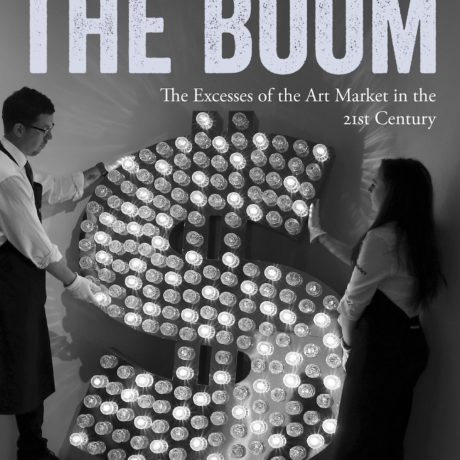

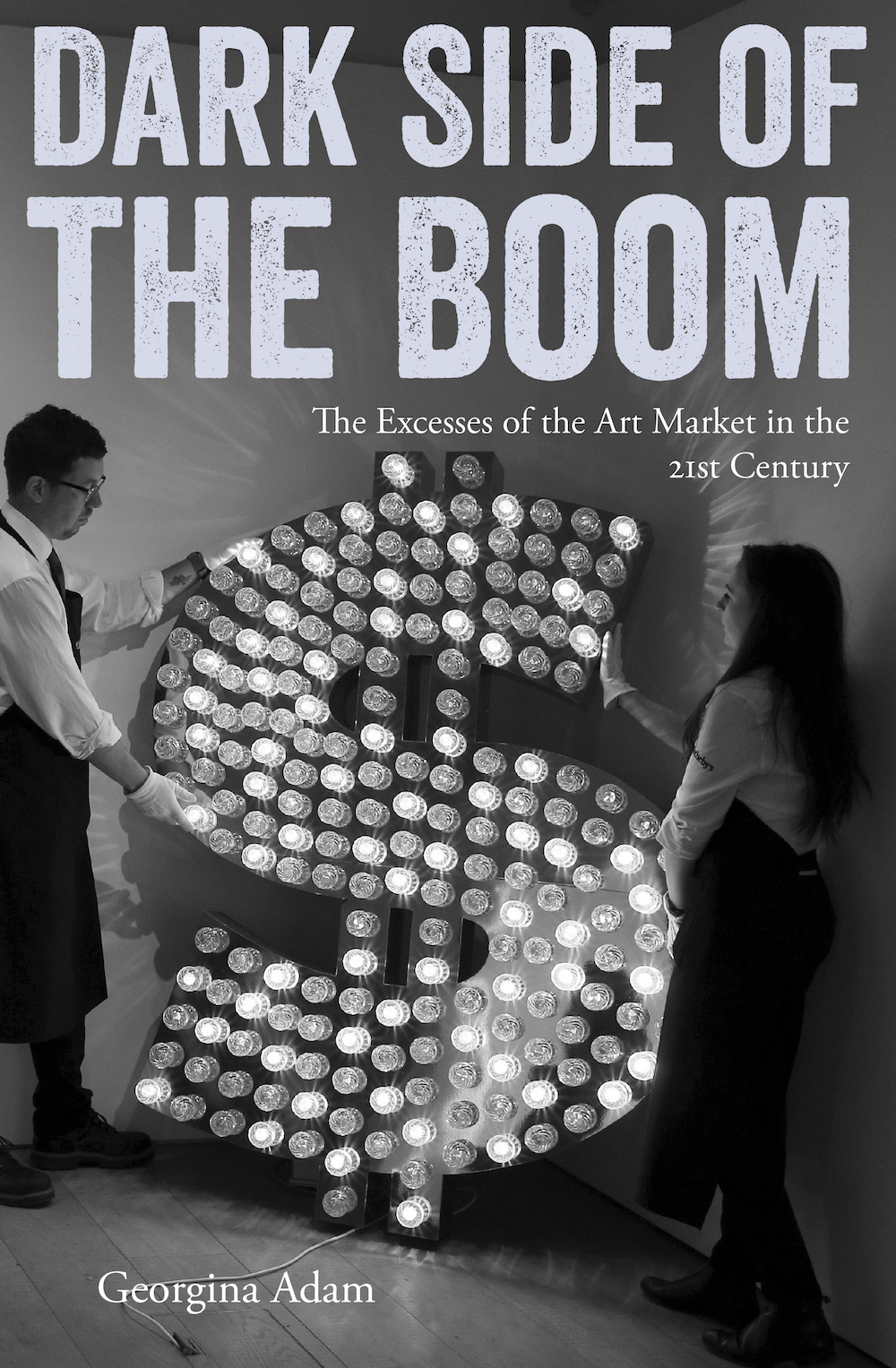

“It’s the Wild West out there,” says one anonymous dealer about the art market in Georgina Adam’s book, Dark Side of the Boom: The Excesses of the Art Market in the 21st Century. And that is someone who is actually in on it. The art market is by its nature secretive and inscrutable, with prices of certain works climbing ten or even one hundred-fold in decades. For those of us—myself included—who know quite a bit about art but virtually nothing about how the buying and selling of it works, this book is a handy intro.

If Adam, the FT columnist and art market editor for The Art Newspaper, outlines an art world of seemingly “unregulated” excess, it is also incredibly vulnerable to modern factors. It’s noteworthy, for instance, that social media has influenced the landscape, from galleries and museums buying works because of how good they look in the background of people’s selfies, to how it has “blurred the notion of authorship”, with not just users but artists believing whatever is online is up for grabs as intellectual property. Artists who went out of fashion decades ago, such as Mel Ramos and Bernard Buffet, have come back into fashion because they are “coherent ‘brands’”. Sotheby’s has dispensed with its online buyers’ premium (for those not in the know, basically art stamp duty) to encourage a new generation of buyer.

“For those of us—myself included—who know quite a bit about art but virtually nothing about how the buying and selling of it works, this book is a handy intro.”

Adam is good on the seedier side: how works are used to launder money, move it easily between countries and evade taxes, leading to their owners even being implicated in the Panama Papers. It seems that on even the highest levels, forgery isn’t actually that difficult. According to art analyst Nicholas Eastaugh, “between 20 and 50 per cent” of the works circulating in the art market now are fakes. Only five percent of works submitted to the Picasso Administration are genuine. Art historian Noah Charney says “There is a tendency for the trade not to let on even if they have suspicions […] There is at least a subconscious desire for a work to be authentic and saleable because it makes money if it is good and everyone loses out if it’s not.” The result is that top authenticators end up legitimizing works signed by Jackson “Pollok”. “Syed Haiden Raza found almost all of a Paris show of his work—put together by his nephew—consisted of forgeries,” says Adam. This is a living artist. In one instance, Peter Doig himself had to appear in court to say a work signed “Peter Doige” was not by him.

Lovatelli Ravarino, who owns some supposedly dubious Francis Bacon pastels that he might even have forged himself, is quoted spelling-mistakes and all, making him seem comically even less credible: “[I] discovered for chance he [Edwards] was goig [going] to make a commercial exhibition in London without asking my permission with some of the drawings and pastels beloved Farncis [Francis Bacon] gave me […] they organized the show in Herrick Gallery withouth [without] informing me […] our goal was to make a cultural show but as the firts [first] aime [aim] of Edwards family was to make a commercial show we had to change the too low values they gave to these items (probabily [probably] because totally anaware [unaware] of commercial market).”

“In one instance, Peter Doig himself had to appear in court to say a work signed ‘Peter Doige’ was not by him.”

Adam’s writing itself occasionally becomes the victim of the attention-grabbing excesses that it describes. “A bombshell hit the players of this cosy world”, “The whole house of cards came crashing down in 2014…”, etc. Each chapter starts with what seems like a first-person colour piece—a studio visit, a freeport opening, an art fair, a “glitzy party”—that immediately tails off into the facts and business-like passages from which the book is primary made (which is actually a relief, as these are far more engaging).

As well as explaining the excess at the very highest levels in the art market, Dark Side of The Boom also functions as a glossary of art-market jargon: VBAs—“very bankable artists” who are extremely unlikely to depreciate—and “investment ready” works. And reading this book is itself a necessary awakening: a bust to the boom. What emerges is how the art market, or at least the “secondary market”—where the big bucks are, once a work has been sold and then resold—actually seems to exclude the producers of art. But artists bite back. When Wade Guyton discovered how many millions one of his works that had been made on an inkjet printer was guaranteed for in 2014, he was “so disgusted” he made it known on Instagram that he could easily make multiples if necessary. Collectors were pissed off, and the work went for a million under its guarantee.

“Reading this book is itself a necessary awakening: a bust to the boom.”

True to inscrutable form, the art market is fluctuating faster than writers such as Adam can document it. Her story is appropriately bookended with “the art scandal of the century”, as she calls it: the self-dealing furore in which Russian billionaire Dmitry Rybolovlev sued the Swiss art mogul Yves Bouvier after it was discovered he skimmed an inordinate amount of profit from the $2 billion of art that passed between them. This continues to resonate outside the book’s pages. Picasso’s Les femmes d’Algiers (1955), cited here as the most expensive painting ever sold at auction ($179.4 million), has since been knocked off the top spot by Leonardo da Vinci’s “Salvator Mundi” and its $450 million sale, resetting the clock on art transactions by more than doubling the previous record-holding figure, and even pipping Cezanne’s The Card Players, which sold privately for $250 million. Unattributed, the Leonardo sold in 2004 for $10,000. The seller, who bought it for $127.5 million in 2013, and made over triple that? Rybolovlev.

Dark Side of the Boom: The Excesses of the Art Market in the 21st Century

Out now with Lund Humphries

VISIT WEBSITE