As Professor Anna Fox has pointed out in her research, the field of commercial photography is dominated by men. Not just by a little bit. Only 2% of the photographers on commercial agents’ books are women. Less than 5% of published photographs in the media and advertising are taken by women.

Only 2% of the photographers on commercial agents’ books are women. Less than 5% of published photographs in the media and advertising are taken by women.

Yet, conversely, in photography departments at universities all over Europe, most of the students are female—about 80% on average across the UK. This is something I’ve noticed too when speaking at schools in Europe about my own book on women photographers, Girl on Girl. I wrote the book out of a similar place of frustration. What happens to all those women? Even more disturbing, is the confirmation that this is how women are represented and seen, out in the world in general.

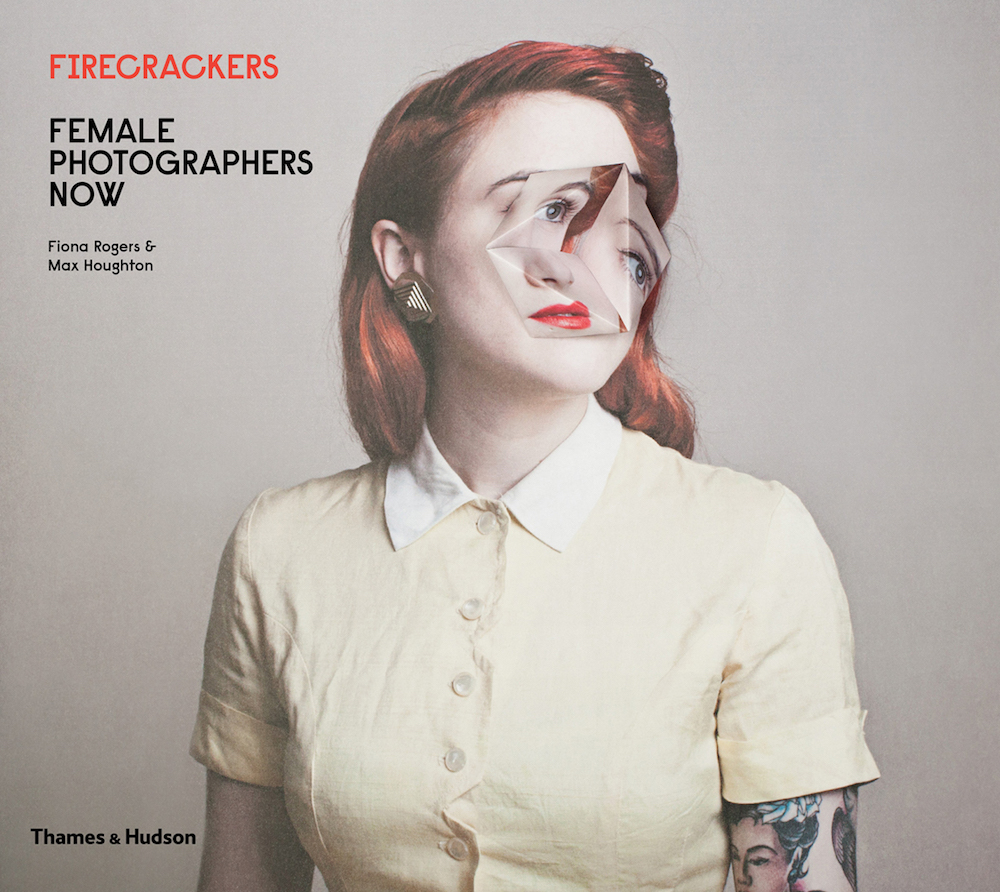

“Firecracker has provided me with a creative outlet for the extraordinary women I’ve met throughout my career, but photography is an industry that is undeniably crowded by (white) men.” Writes Rogers in her introduction to Firecrackers, talking about the platform for supporting the work of female photographers she founded in 2011. Rogers is also the global business developer at Magnum Photos. “It’s by no means the only industry in which this happens, of course. Life imitates art and vice versa. With so few women represented at the highest levels in contemporary art, politics and the media, it’s no wonder there is a lack of diversity in photography – and it’s not just a gender issue either (but that’s another story, and indeed another book).”

Photography, like all other art forms, has been dominated by the men and the male gaze since incipience. As much as it appears from the media attention on the subject that things are changing, statistics and experiences like these tell a different story.

“It’s absolutely essential that we make way for female photographers and visual artists; otherwise, we keep seeing repeated male visions of the world, and come to believe it as a truth,” Max Houghton said in a recent interview. “We are talking about entrenched practices of patriarchy and unfreedom and the reason we are still talking about such issues is because they persist.”

“It’s absolutely essential that we make way for female photographers and visual artists; otherwise, we keep seeing repeated male visions of the world, and come to believe it as a truth,”

The female gaze is not monolithic, by any means, but what’s particularly interesting about Firecrackers is that the authors have also looked at work that perhaps could only have been made by women—for example, Behnaz Babazadeh, who made a film about a BDSM woman who had burkhas custom-made in latex, and has since explored the fetishistic side of the burkha in her photographs, remaking burkhas out of different materials, including gummy bears and candy corn. Another is Endia Beal, an American educator and activist who has photographed, whose series include a documentation of the hairstyles of middle-aged African American women, and South-African visual activist Zanele Muholi, who has spent more than a decade documenting her LGBTI+ community.

While the fields of war photography and political photojournalism have been especially dominated by men, Rogers and Houghton emphasize women working with these subjects in difficult circumstances, and suggest that their vision might be distinct from a man’s: two striking examples are Magda Rakita’s images of the aftermath of civil war in Liberia and Laura El-Tantawy’s snapshots of the turbulent political atmosphere in her native Egypt.

I couldn’t agree more with the impetus of Firecrackers, that it is worth celebrating women photographers, whilst at the same time, validating the importance of the work beyond that. The book is described as “timely”, but perhaps its real value is for posterity—to change the way women photographers are framed and talked about, making their contributions clear. As for changing things in the present, it’s an ongoing battle as in every field to get women to an equal position. As Rogers and Houghton point out, to do that, sticking together is key.

Firecrackers by Fiona Rogers and Max Houghton is published by Thames and Hudson.