Photo by Alfred Athis Natanson, Vaillant-Charbonnier collection

“To have attained the famous three-score years and ten,” wrote the American critic Walter Pach in 1912, “and be producing work which surpasses that of his youth and middle age, to have seen the public change its attitude from hostility to homage, to be one of the best-loved living painters: such is the lot of Pierre-Auguste Renoir.”

Over a hundred years later, homage has visibly reverted to hostility in some camps. There is no dead painter who receives such active disapprobation. People don’t just ignore Renoir (1841-1919), as they might other unfashionable greats such as Rubens—an artist Renoir loved so much as a teenager that the guys in his porcelain workshop would call him “Monsieur Rubens” and make him cry—they go out of their way to express disgust, picketing not just exhibitions, but permanent collections featuring work by the artist. Two years ago it became a hashtag (#RenoirSucksAtPainting) then a meme, then a movement. People holding “God Hates Renoir” or “Treacle harms society. Remove all Renoirs now” signs were all over Instagram. This was down to the perceived misogyny of the way he depicted women and the sugariness of his inner worlds.

The Philadelphia Museum of Art, bequest of Carroll S. Tyson, Jr. The Philadelphia Museum of Art, The Mr. and Mrs. Carroll S. Tyson, Jr. Collection (1963-116-13)

And yet, he is still popular among many and has a wide-reaching appeal. His works have an immediate quality; a power and warmth that appeals to the untrained eye. And those who hate him must concede that he is an immediate father of modern art. (The giants of the early twentieth century, Matisse and Picasso, saw him as one, so you have to take their word for it.) He produced over four thousand paintings in his half century of productivity and six hundred other works. In an act of parallel Herculean endeavour, Barbara Ehrlich White, the author of Renoir: An Intimate Biography, has sifted through over three thousand published and unpublished letters from, to or concerning the artist to get us closer to the man. (The majority of these were hunted down by Ehrlich White herself.) But is that somewhere we should want to be?

“Today he is unfairly and inaccurately denigrated and accused of being an anti-Semite and sexist,” says Ehrlich White. “I believe Renoir was neither.” But then, you can hardly expect the leading Renoir authority to be entirely critical of her life work’s subject. As demonstrated in this book, Renoir was sometimes more socially enlightened than your average nineteenth-century Frenchman, in some cases less so. One the one hand, he showed an unstinting respect and camaraderie towards Berthe Morisot, and never communicated that he thought she was inferior to the male Impressionists. On the other, he thought George Sand was “monstrous” for having the gall to compete with men on the literary playing field.

National Museum, Stockholm

There are many instances of casual chauvinism in his life that will certainly annoy modern readers. “Renoir wanted Aline [his wife] to take care of her looks and expressed concern about her figure, yet was resigned that she would do as she wished,” etc. There are other problematic things that you can imagine will be manna for the #RenoirSucks camp. In the summer of 1874, “Something happened between Renoir and Charles’s [Le Coeurs] eldest daughter, Marie, then aged fifteen, that led to Renoir’s banishment from the family.” Either he was caught spying at the keyhole of her bedroom while her and two young cousins had been “dancing by candlelight in their slips” or he had tried to arrange a rendezvous with her.

“If you seek moral courage, don’t come to Renoir.”

Ehrlich White explains Renoir’s misogyny in light of the place as well as the time. In France, women didn’t get the vote until 1944. Property passed from a man to distant relatives before it would go to his wife. Espousing feminist opinions at the time would have made Renoir appear a “radical, something he avoided scrupulously throughout his life” so as to get work and patronage from rich conservatives. If you seek moral courage, don’t come to Renoir. And if there is a prominent misjudgment in Ehrlich White’s approach, it is the ambiguity as to whether she is explaining or excusing Renoir. If the latter, many defences seem to rest on citing Renoir’s utter spinelessness as if it wasn’t in itself a negative quality. Antisemitism is at one point blamed on his “manipulative personality”.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Walter H. Annenberg, Bequest of Walter H. Annenberg, 2002

It is hard to woke the Impressionists, to square them with modern sensibilities. Especially at this very political moment, following the #MeToo movement. For one thing, barely any of them had relationships with women that didn’t start in the workplace, when the woman was beholden, often younger, physically vulnerable in the extreme: alone and naked. As the author of this book says, Renoir “was always on the lookout for pretty women to model, and attraction and flirtation were part of his relationship with models.”

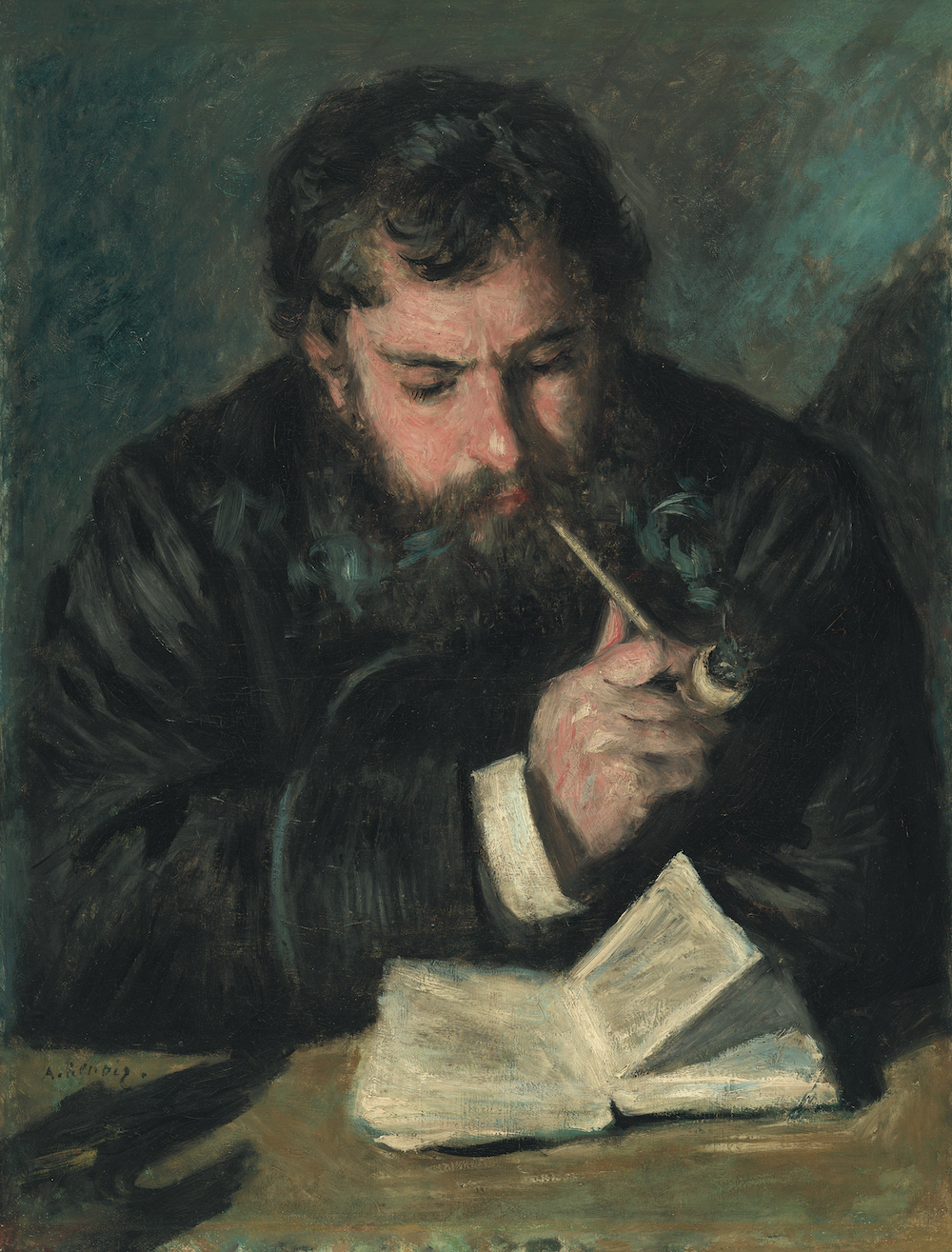

So, discounting all of this, does the art make a better case for him? His nudes, especially from the 1880s and onwards, are often criticized for their sensuousness without seriousness, the vacancy of their smeared and slightly feverish faces. Their lack of visible inner life or agency. Ehrlich White identifies why Renoir’s females all look similar and indistinct at the same time. “Now, as always, it is impossible to identify which model posed for which figure, since Renoir not only painted the same model differently but also sometimes used different people as models for the same figure.” His works (The Boating Party, Blonde Bather, Dance at Bougival etc.) all have different versions of his future wife Aline. But Renoir wasn’t capturing a specific woman, more often than not, but composites representing the idea or the ideal of a woman. And this, right here, is the problem. In painting men he painted the sitter; in painting women he painted via them.

Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon

Many of Renoir’s female sitters in formal commissioned portraits, from decade to decade, from style to style, looked interchangeable, despite age and temperament. It is visible simply working from the plates of this book. In a strange coincidence, Julie Manet—Morisot’s daughter (and Édouard Manet’s niece), who would grow up to be a politically active anti-Semite, donating money to causes for the repatriation of Jews to Jerusalem—painted as a young girl in 1887 has an almost identical face to the adult wife of Renoir’s Jewish patron Gaston Bernheim, painted in 1910.

All his models blended together into what people now see as a lack of expressiveness or interiority. The effect is like an artistic collaboration in which individual voices are ironed out, but in the case of the subjects instead of the artists. You can see why this has harmed him. But there is something artistically fitting, at least in that it is truly impressionistic. A mood; a flash of life washing over itself; human landscapes; a motion not just of human bodies but identities. An impression of people. And these images seem more alive, visceral and true to Impressionism and coming artistic eras than Renoir’s accurate depictions of men. One can’t imagine Picasso having the ability to see beyond what was in front of him—to tamper with reality in order to get at a new reality—without the example of Renoir, who reimagined how bodily voluptuousness could be shown geometrically in a two-dimensional medium.

“The similarity of Renoir’s world to ours is quite shocking. He was coming of age as an artist during a recession.”

Renoir’s outlook—simply and idealistically trying to capture beauty and sensuality (both of which are relative and constantly in flux)—is certainly not in fashion now. I can’t imagine a time when they would be less in conjunction with our political moment because escapism has itself never been so unfashionable. (“Treacle harms society. Remove all Renoirs now.”) But then, the similarity of Renoir’s world to ours is quite shocking. He was coming of age as an artist during a recession. The banks had failed and France was paying indemnity to a newly unified Germany after the Franco-Prussian war. Despite people now seeing the period as a time of bohemian morals—mostly because of Impressionist imagery: all that idleness and seduction along the banks of the Seine—it was a time of deep conservatism and nationalism. If the world doesn’t need Renoir, perhaps those looking to capture our times today might do well to think hard about those supposedly soft images.