If you can remember the ‘60s, so the saying goes, you weren’t there. Silly though the assertion is, it strikes at least a ring of truth. Of course people who lived through the 1960s remember what happened––but so do many of us who didn’t. For as long as I can remember, the mythology and history of that decade have been rammed into my generation’s consciousness, its music, literature, journalism, politics and film framed as peaks in the known terrain of cultural history. Back then, we are told, there were things worth rebelling against; that individual identity was not commodified; that the creative ideas coursing through New York, London and San Francisco were not only more original than any since, but of genuine historical consequence. The music was better––and so, of course, were the drugs. I wasn’t there in the ‘60s. But given the déjà vu I feel whenever the decade’s editorially sanctioned legacy comes into discussion, I honestly feel like I might as well have been.

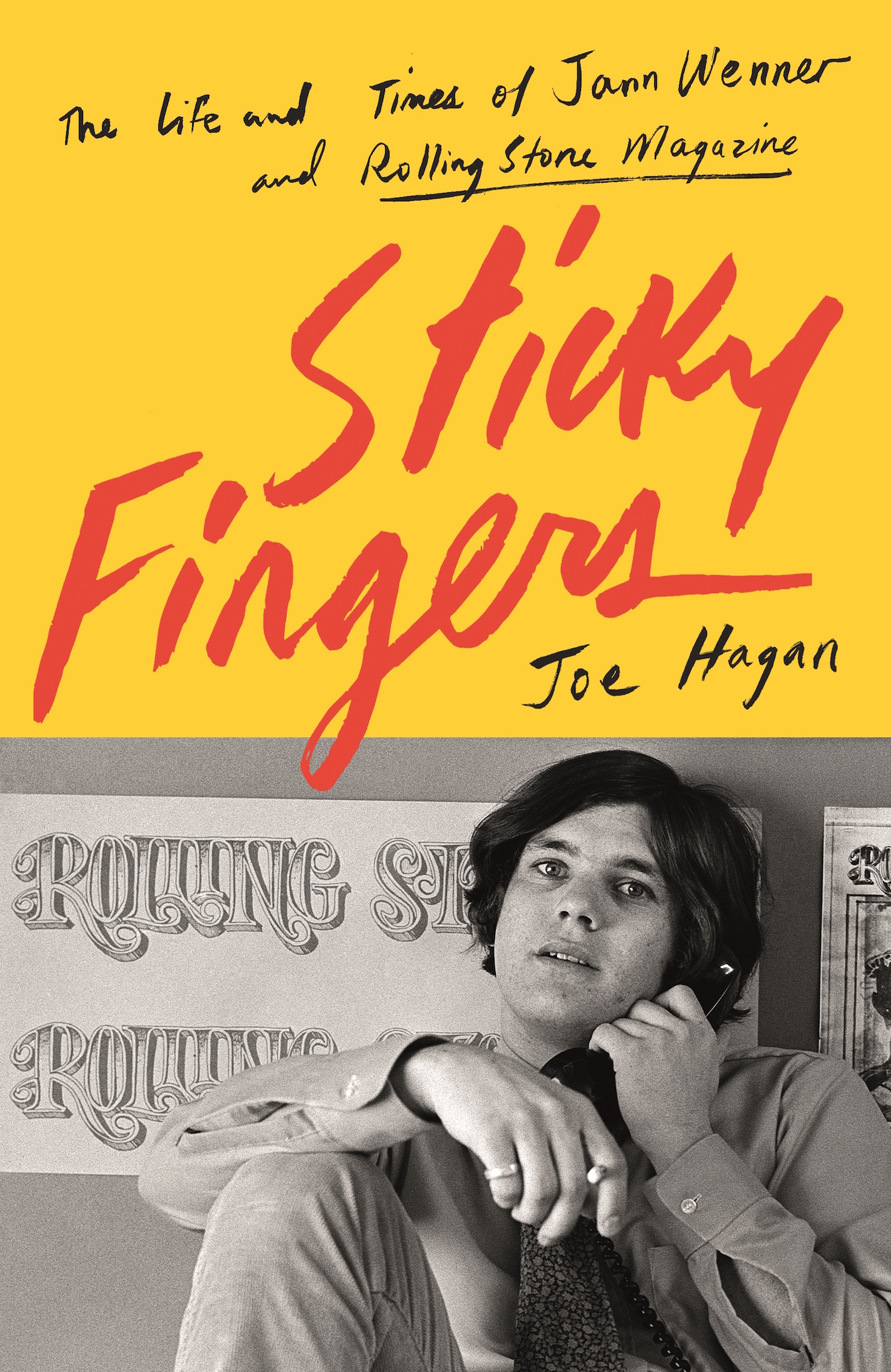

Will we ever have an objective view on the era? Part of me suspects not. But to his immense credit, journalist Joe Hagan has got closer to the essence than most with his biography Sticky Fingers: The Life and Times of Jann Wenner and Rolling Stone Magazine. Hagan, who grew up reading Rolling Stone––more or less the official codex of the swinging sixties––was granted unfettered access to its founder Wenner, who once the book was finished dismissed its contents as “tawdry.” As well he might have done. Because the picture it gives us is a rather different account from the one he has spent the past 50 years cultivating in the pages of his hallowed title.

“Of course people who lived through the 1960s remember what happened––but so do many of us who didn’t.”

Born in 1946, Wenner was a Jewish kid who grew up outside San Francisco and came of age just at the moment the Beatles made the jump to transatlantic stardom. He had been raised unconventionally––his father a successful businessman who made a small fortune off the back of patenting baby formula, his mother a proto-hippie and the author of a racy dime store novel––and was expelled from school before finally settling at an elite boarding institution in Los Angeles, where fellow pupils included Liza Minelli. Editing a school newspaper there, the podgy, outspoken and toxically ambitious Jan (in order to sound more “Scandinavian”, so Hagan suggests, he added the extra ’n’ later on) discovered his twin callings: muck raking journalism and shameless social alpinism. As Hagan would have it, this latter preoccupation made him fixated on getting into Harvard. He didn’t, ending up at Berkeley.

The academic rejection turned out to be a blessing in disguise. San Francisco was fast becoming the nexus of the nascent counterculture, and with Rolling Stone––which Wenner established in 1967 off the back of a no-hope underground publication––he would see to it that its deadbeat folklore became the stuff of legend. Rolling Stone’s beginnings really are fascinating. As Wenner saw it, it was a bridge between no-hope underground publications of the Oz variety and the mainstream, containing straight prose that addressed subjects that were anything but. (Indeed, RS’s early incarnation seems to have been powered on a diet of high grade LSD and hash. Wenner would later take to paying bonuses with grams of cocaine.)

Within 18 months of establishing his print mouthpiece on a pitiful budget, the 22 year old Wenner was already chasing his way to the top, calling Mick Jagger a friend (he wasn’t, as far as Hagan is concerned) and successfully courting the attentions of his hero, John Lennon. Yet for the time being, Wenner’s aggressive schmoozing was justified by the fact that he was putting out first-rate editorial. Jon Landau, a trenchant critic and later Bruce Springsteen’s manager, was Rolling Stone’s lead album reviewer; Tom Wolfe contributed a series of articles that would later become The Right Stuff; and Lester Bangs was making a name for himself as one of the most inspired music writers of the day. (In a review that ultimately got him fired, he described Springsteen as “sorta like Robbie Robertson on quaaludes with Dylan barfing down the back of his neck.”)

And then there was Hunter Thompson. Well, wow. Wenner cottoned on early, commissioning and serialising Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas in his pages, all the while weeping over the expense claims submitted by his soon-to-be star writer. For a while, Thompson shines as an indestructible, acid-fuelled exemplar of an anti-establishment journalistic dynamo. For a few years, he can do no wrong, and Wenner comes to hero-worship him both as a macho idol and as a cash cow for his often struggling magazine. But by the end of the 1970s, he was burned out. And so, despite its growing circulation, was Rolling Stone.

“Wenner’s aggressive schmoozing was justified by the fact that he was putting out first-rate editorial.”

The gossip Hagan provides is top-notch––who knew that Mick Jagger and long term Rolling Stone photographer Annie Leibovitz had an affair?––his research unquestionably scrupulous and his prose stylishly dry. But Sticky Fingers is a painful read at times, mostly because its subject is so difficult to like. Quite apart from his preposterous ambition, Wenner (who at one point in the 1970s, mulled over the possibility of a run at the White House) comes across as a manchild possessed of next to no self-awareness and an overwhelming anxiety as to how others perceived him. If Alan Partridge had grown up in the Bay Area, you sense, he may well have ended up the subject of a very similar biography.

A good two thirds of the book is taken up by Rolling Stone’s first decade, but what follows is arguably more interesting. In short: against the wishes of his staff, Wenner moves his business to New York to secure ad dollars, develops a truly heroic coke habit and utterly loses touch with the youth culture he always claimed to represent, instead becoming the self-styled “keeper of the rock’n’roll myth”: publishing endless covers of the pasty faced rock stars of whom he had grown up in awe, thus repackaging the 1960s counterculture as a tradable commodity.

Despite skyrocketing revenue, the magazine sops to fawning profiles of Wenner’s glamorous social circle (Jagger, Bono and, improbably, John Travolta and Jamie Lee Curtis), making a point of ignoring musicians – especially black musicians – producing vastly superior records. (“I rarely put RnB acts on the cover,” Wenner said of his refusal to cotton on to Michael Jackson’s Thriller.) I won’t ruin it for you – this will do that nicely – but what follows is far from a happy denouement, the blame for which is attributed in no uncertain terms to Wenner’s greed and professional negligence.

Yet for all his faults, Wenner is far from the most monstrous of Sticky Fingers’s cavalcade of grotesques, slapping down his macho editorial board for trivialising an Ellen Willis piece on rape and giving prominent coverage to the AIDS crisis when most other publications would barely acknowledge it. Compare this to the treatment accorded his contemporaries, and Wenner seems the very figure of an enlightenment capitalist. As Hagan reminds us in his introduction, Wenner was just one of a generation of avaricious self-mythologisers––an exact contemporary, in fact, of Donald Trump. All considered, perhaps that presidential campaign wasn’t such a fantasy after all.

Sticky Fingers, The Life and Times of Jann Wenner and Rolling Stone Magazine by Joe Hagan

Out now with Canongate

VISIT WEBSITE