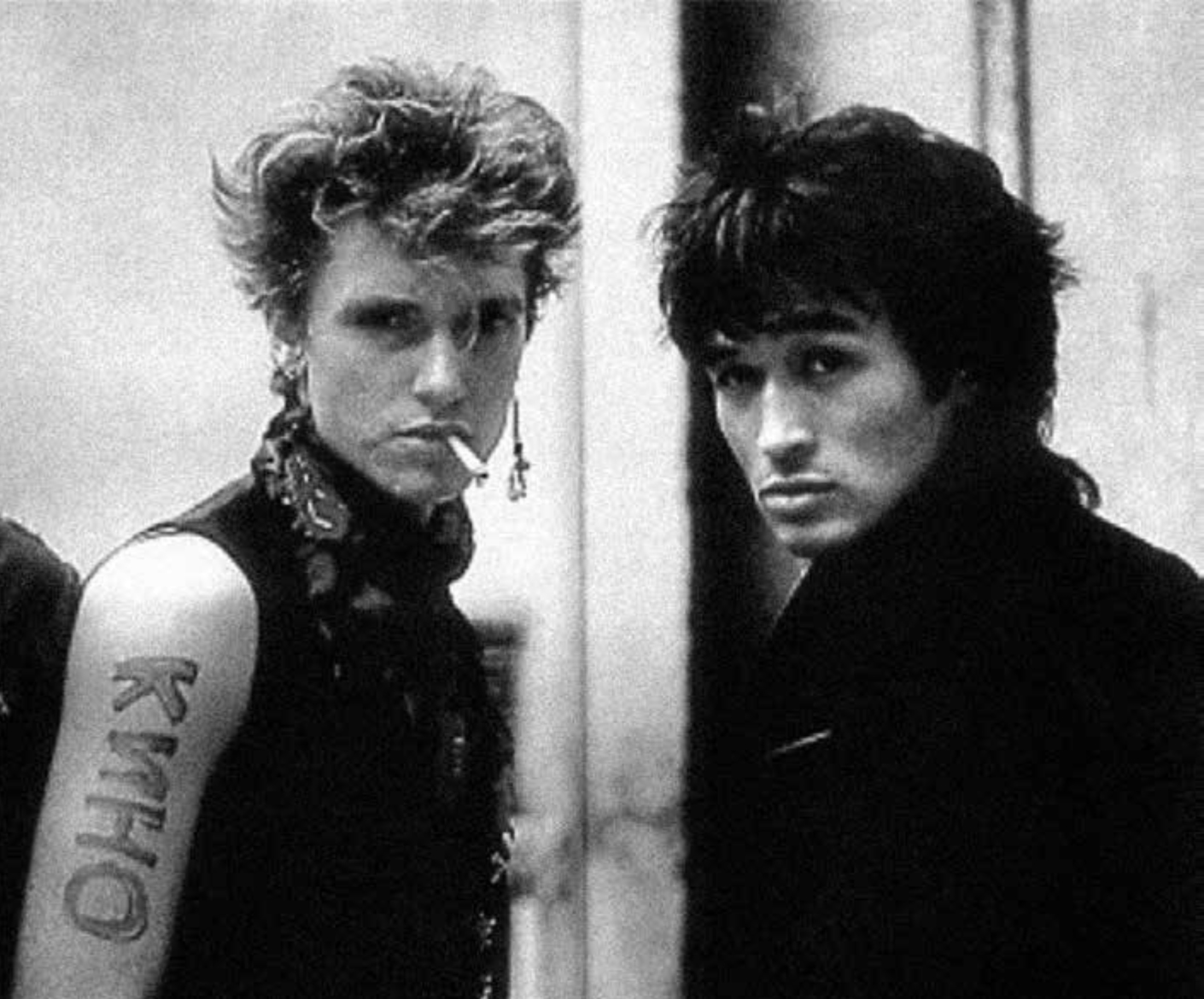

As Jon Savage writes in the book’s foreword, “you can tell a lot about a country by the way it treats its youth.” He should know—he wrote the book on it (Teenage, 2007). Subkultura deliberately resists traditional and official Russian history, with Troitsky looking at the rebellious souls who have shaped the nation through social and political resistance and underground cultural movements: from visual art to rock music, anarchists to punks, dandies to philosophers.

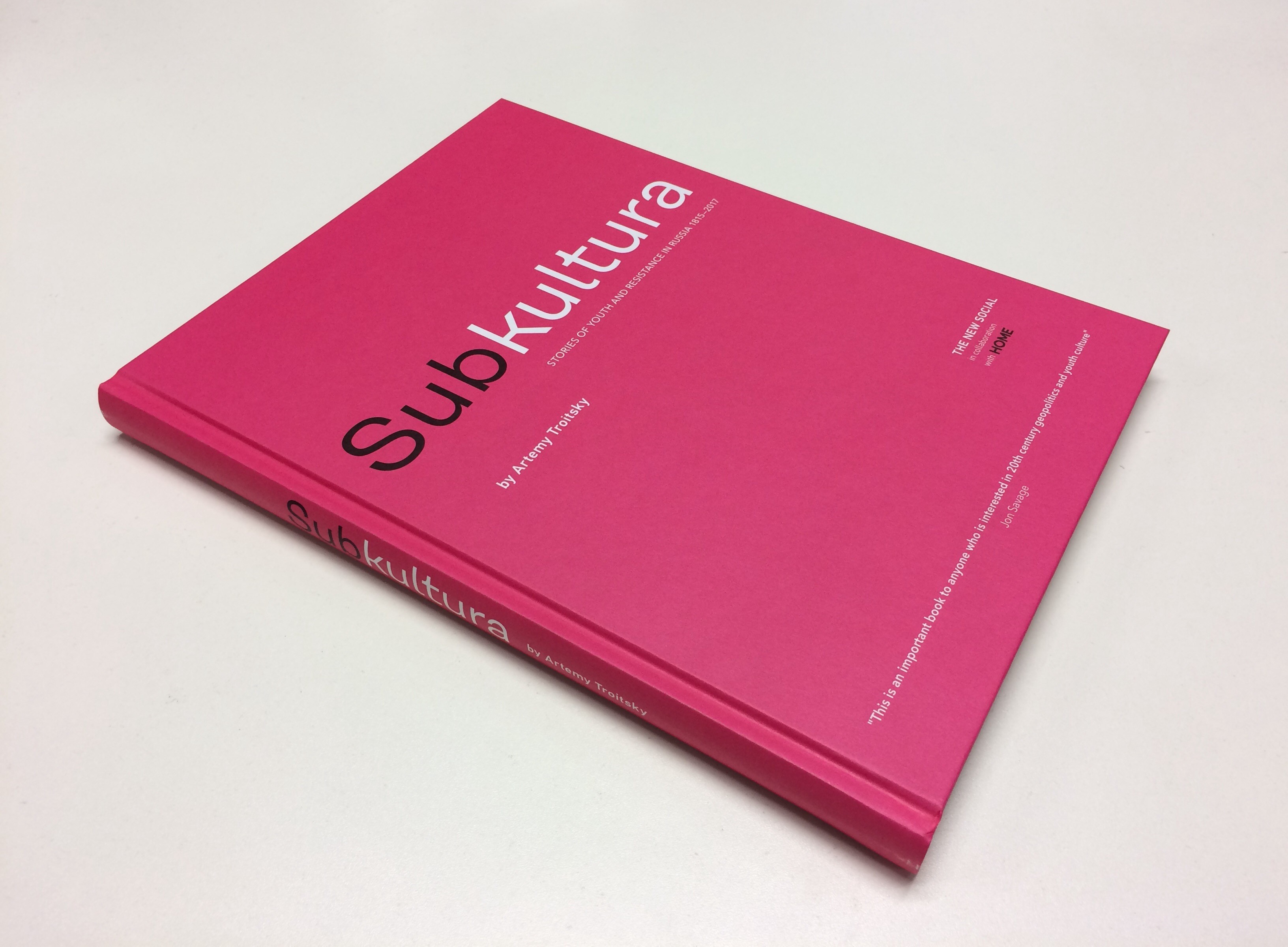

Published by Manchester’s HOME in collaboration with The New Social collective, the book is part of their joint programme related to the centenary of the Russian Revolution, culminating notably in their major exhibition The Return of Memory (21 October–7 January 2018). Founded by Olya Borissova and Anya Harrison, The New Social is a London-based collective that seeks to stage public programmes that rethink the “New East” (Eastern Europe, the Balkans, Baltic, Russia and Central Asia). Akin to Troitsky’s narrative, which focuses on the effect of the past on the present, the exhibition shines a light on unofficial histories, suppressed memories and strategies of political resistance in order to explore the legacy of the Russian Revolution on contemporary artists working today. How do people re-invent themselves, or what patterns continue to recur?

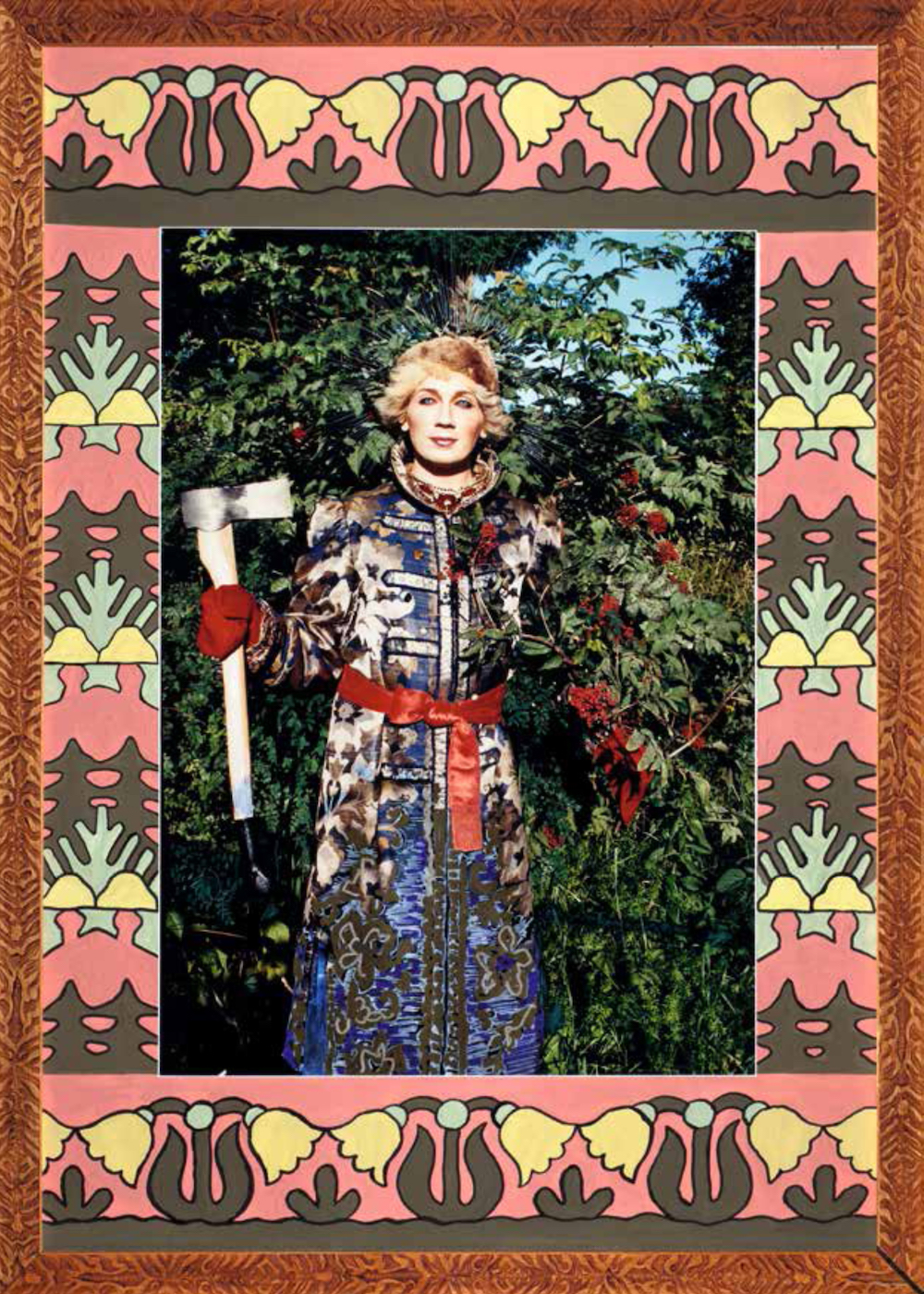

Troitsky’s “alternative” history is designed to be understood in two ways: as unconventional and with a sense of revolution at its core, but also as an alternative to the stories of tsars, generals and secret policemen who are eschewed in favour of the creative, independent young people who fought and continue to fight against those very characters. For a reader like myself, saturated with the history of British, European and North American subculture or youth movements, Troitsky’s book also feels alternative because it feels less heard—oppressed by Russian state-sanctioned narratives and perhaps sidelined by cultural historians. It also includes archival photography and artwork from Troitsky’s varied and extensive personal collection. Troitsky’s voice is a crucial part of the narrative, set up by his personal introduction and grounding of the project in the tough reality of life in Russia today.

“I decided to write this book because I felt the state of Russia today compelled me to,” he writes. “We are currently experiencing a period of darkness—one that for many people seems to be without help. There was a time when I dreamed of writing a gentle, fatherly book [for my children] about this vast country I love so dearly… I can’t do that right now. The story this book will tell will be different: unsentimental, even frightening. But maybe it will be inspiring too—and that’s why I have to write it”.

Troitsky cites a common dynamic between generations of Russian youth over the past centuries: their inquisitive nature. “They don’t yet really know what life is about, but they want to know; they’re not satisfied with life but they want satisfaction… they want to find [their place in the world]—they want to find others like them.”

The notion of finding others “like them” is what drives the concept of subculture, to join forces with others in order to create a shared ideology and a shared lifestyle. He focuses on “home-grown” groups that were unique to Russia, not paying heed to any unconvincing copies of Western movements. The book is organized chronologically, each of the eleven chapters explores a distinctive period from the last two hundred years. The narrative moves from the Dandies and Decembrists of the mid-nineteenth century to Nihilists, Popularists, Marxists and Reactionaries, mystic cults, the Komsomol, the Soviet youth and dissidents during the Iron Curtain, to 1980s rock, 1990s ravers and the apathy of Gopnik, to protest groups united against a surge of contemporary nationalism. It is an extensive and expressive ode to the “passionate and peculiar”, the true heroes of Russian history.

Subkultura

Out now with HOME