Trolley Books publisher and director of London’s TJ Boulting gallery, Hannah Watson works around the corner from The Fitzrovia Chapel, the only surviving building of what used to be the Middlesex Hospital, where the first Aids ward in London was located, opened in 1987 by Princess Diana (the hospital closed in 2005). In 1993, photographer Gideon Mendel was at the ward and took pictures of the patients, their families, loved ones and the doctors, nurses and therapists who supported them. Earlier this year Watson, a trustee of the Chapel, was asked by the Chapel’s artistic director if she knew Mendel. “I knew his recent work, but I had no idea that he had done this project,” Watson explains. This summer, she met Mendel in Arles during the photography festival. “As soon as I saw the images I knew it should be a book; it was a knee-jerk reaction although to start with I tried very hard to think small as I had no time or money to start thinking about a book. In the end, it did become a proper, beautiful little book. The work definitely deserved it.”

Working with images of the dying wasn’t an easy experience. Watson said she found herself moved to tears many times looking through the materials. “It’s been very emotional working on this book! The image of the elderly mother tightly holding the hand of her son while stoically looking up at the medical team always gets to me. She, like everyone at the time, had no idea what was going on but was there by her son’s side through everything.” Watson reflects. The Aids epidemic, the deadliest in human history, has taken the lives of more than twenty million, most of them gay and bisexual men. In the UK today, an estimated 101,200 people are living with HIV.

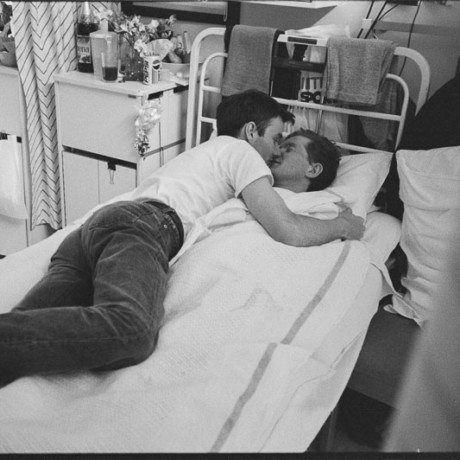

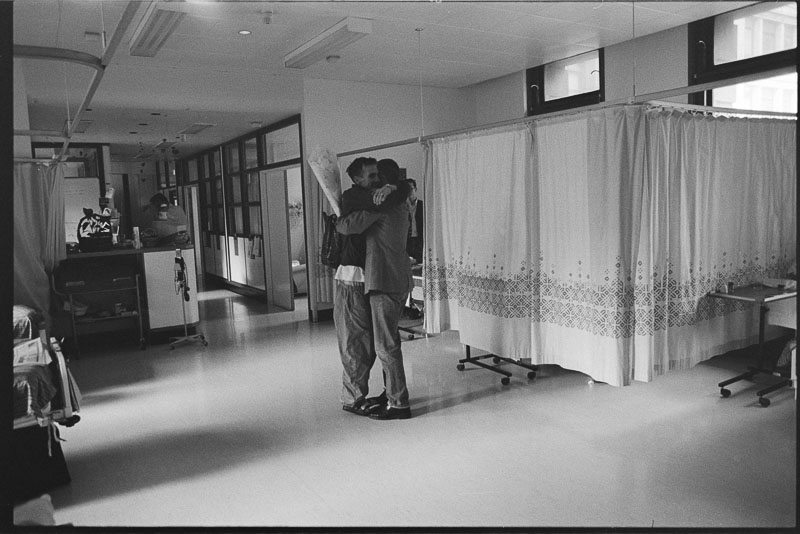

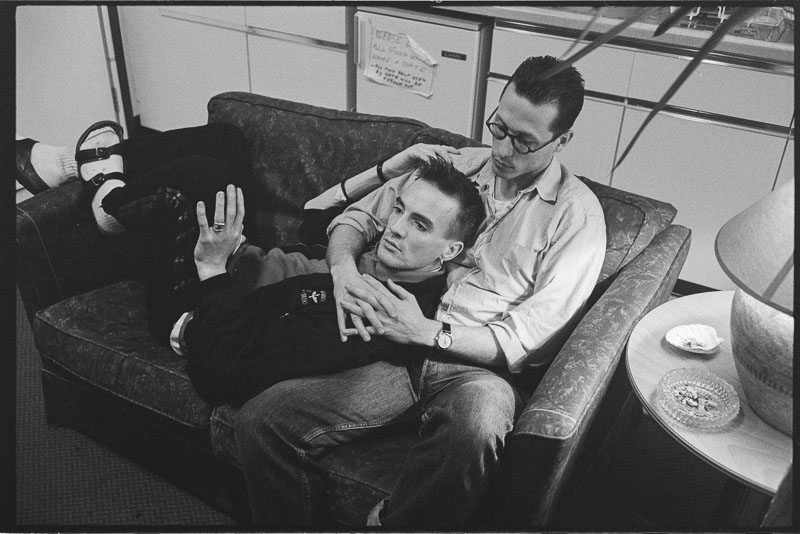

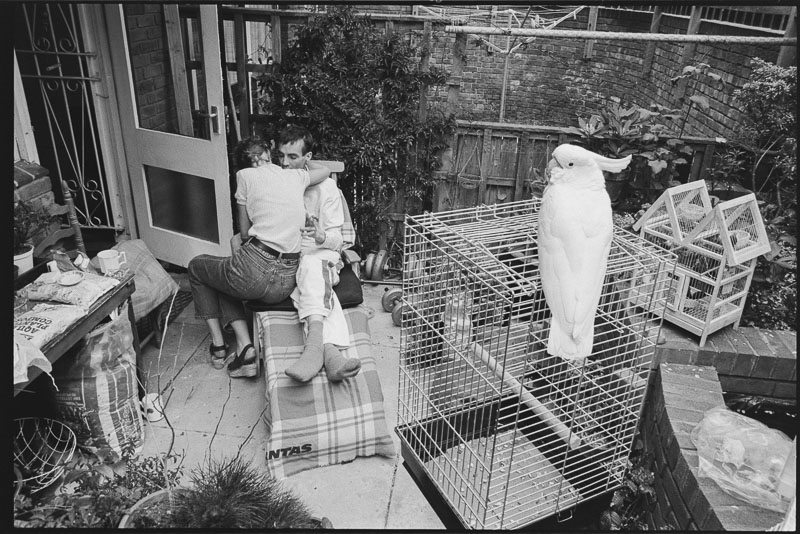

“There is an overwhelming sense of love when you look through the pictures, lots of hugging and kissing between the patients, friends and nurses. In some of the images, it doesn’t even look like a hospital until you see the curtain or a nurse in the background.” The images are accompanied by moving personal texts, almost twenty contributions from friends, the staff at the hospital and visiting therapists, and other medical staff, such as the shiatsu therapist who used to give the nurses treatment.

The book is not only a personal, final portrait the patients who were at the hospital, something for those they left behind, but a celebration of a remarkable moment in local history, where love overwhelmed fear, a community of people helping each other against an incurable disease that was not only devastating to sufferers but profoundly stigmatised at the time. Though now defined as chronic, rather than fatal, over 36.7 million people are living with the disease worldwide.