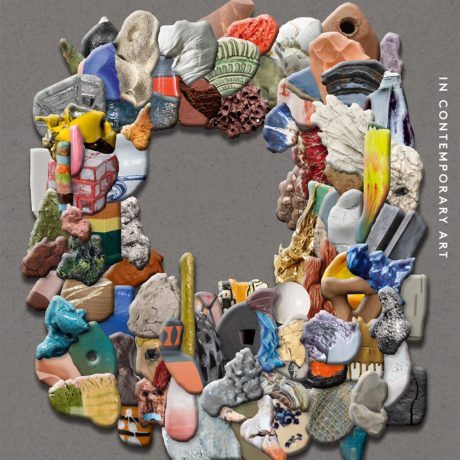

Part of Luster – Clay in Sculpture Today exhibition, Fundament Foundation at park De Oude Warande, Tilburg, Netherlands, 2016

Courtesy Fundament Foundation

“Our writers unravel the appeal of clay’s material working processes. It is described as being rolled, ripped, pulled, prodded, perforated, squeezed, poked, kneaded, fingered, folded and fragmented, its tactility and bodily resonance seeing artists using dextrous fingers and palms to activate the earth.”

—Louisa Elderton and Rebecca Morrill, Editors, Vitamin C

Vitamin C: Clay and Ceramic in Contemporary Art is the latest addition to Phaidon’s extensive medium-specific Vitamin series. The book operates as a detailed survey of contemporary artistic practice, showcasing over one hundred artists working with a certain medium. Previous editions have focused on painting, drawing, photography and sculpture. Each of the 102 artists has their own profile within the book, nominated by an extensive board of leading curators, critics and art professionals, including Iwona Blazwick, Udo Kittelmann, Nancy Spector, Sheena Wagstaff and Christine Macel, among others.

Courtesy the artist and Rob Tufnell, London. Photo: Andy Keate

In recent years there has been a change in the perception of clay and ceramics, now appreciated and consolidated within the tradition of “fine art”, as opposed to as “craft”. This shift towards ceramics could also be due to a wider embrace of cross-disciplinary practice in visual culture today, or the wider fashion in recent years for the artisanal and the handmade. There has been a surge, too, in adult pottery classes. Exhibitions in 2016, such as the Californian counter-cultural figure Ken Price at London’s Hauser and Wirth, or The Sunday Painter’s presentation of British post-war ceramicist Gillian Lowndes’s idiosyncratic sculptural work, depict how artists working in the ceramic world have been equally daring, radical and transgressive as their peers working in the plastic arts. The 2017 exhibition at Tate St Ives— That Continuous Thing: Artists and the Ceramics Studio, 1920 – Today—was organized by Aaron Angell. Angell, who founded London’s Tory Town Art Pottery, is part of a new generation of UK based artists who are reconsidering ideas of art and craft, along with innovating a communal and collective-orientated workshop practice. In a Frieze interview with Angell, cited in the book, he comments, “To answer the question ‘why now?’ I think there is certainly a reaction against the kind of fabrication fetish that we have been seeing in a lot of work over recent years.” Richard Slee, another featured artist in the book, suggested in the wake of ceramics being dropped from the school curriculum in Britain (ceramics education in Britain in particular was removed from many schools and art colleges in the late 1980s), “sometimes, if you take something away for a period, it becomes attractive again.”

Courtesy Alison Jacques Gallery. Photo: Robert Glowacki

In 2015 the Cass Sculpture Foundation in West Sussex commissioned the build of a wood fire kiln in response to the increasing number of contemporary artists using ceramics, in order to provide access to this rare traditional kiln process. Camden Arts Centre runs a successful and renowned Ceramics Fellowship, designed for “artists who wish to push the boundaries of their ceramics practice” and who are able to “promote their approach to making across education activities and public programme”. The Grantchester Pottery—who also features in Vitamin C—undertook the residency in 2016, running open studios and exploring the boundary between art and design in relationship to ideas of authorship and collaboration. This autumn Tate Exchange played host to Clare Twomey’s Factory, encouraging visitors to join the thirty-metre production line, complete with forty factory staff, eight tonnes of clay, a wall of drying racks, and over 2,000 fired clay objects.

Courtesy Hollybush Gardens and the artist, Courtesy Modern Art Oxford. Photo: Ben Westoby

The central essay to the book—Haptic Art—is written by Clare Lilley, the Director of Programme at Yorkshire Sculpture Park. It situates clay as an ancient and abundant material, one of the natural world’s protean resources, which has been used for millennia. Art critic Roberta Smith is quoted saying that ceramic “has one of the richest histories of any medium on the planet”, and presses that the divide between art and craft is “bogus”. Lilley traces the history of clay, from the early human compulsion to create art in the pre-historical period, to its ubiquity throughout the story of art—Rodin, Picasso, Giacometti, Miro, Noguchi, et al. She continues to explore this history through the context of museum and galleries, citing the representation of artists like Rachel Kneebone or Betty Woodman by commercial galleries as iterating how the boundaries have shifted.

Courtesy the artist, Isabella Bortolozzi Galerie, Berlin, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, David, Kordansky gallery, Los Angeles, Salon 94, New York. Photo: Jeff Elstone

Contemporary culture has eschewed traditional interpretations of ceramics as only vessel-based, decorative or functional objects, or the relegation of clay as a preparatory stage before creating a more “serious” sculpture, in bronze for example. Along with multifarious sculptural practice, many artists also amalgamate ceramics with other mediums as part of an exploratory approach to materials, or incorporate them into performances, installations, animation and video work, relishing in its versatility or unpredictability. It would be a feat to list each artist featured in this mammoth 300-page tome, but here are some of many more names, which should help to convey the international breadth and depth of the project: Ai Wei Wei, Ghada Amer, Lynda Benglis, Huma Bhabha, Kathy Butterly, William Cobbing, Liz Craft, Lilibeth Cuenca Rasmussen, Phoebe Cummings, Rachel de Joode, Edmund de Waal, Nathalie Djuberg and Hans Berg, Rose Eken, Alexandra Engelfriet, Emily Hesse, Lubaina Himid, John Kørner, Klara Kristalova, Simone Leigh, Alice Mackler, Mark Manders, Ron Nagle, Ruby Neri, Paulina Olowska, Gabriel Orozco, Damiàn Ortega, JJ PEET, Mai-Thu Perret, Tal R, Sterling Ruby, Anders Ruhwald, Wael Shawky, Rosemarie Trockel, Jesse Wine… phew!