Supriya Lele has just got a new puppy when we speak over the phone, and is still learning to adapt her schedule. “At the moment I’m like a new mum!” she laughs. It is a new grown-up chapter for the British Indian designer, whose sensual yet relaxed womenswear collections draw as much upon her own family heritage as they do her teenage interest in heavy metal and grunge. Lele came of age in the late 1990s and early 2000s, an era that still colours her visual outlook today. Now 33 years old, she leads an all-female team who draw on a unique combination of influences, from traditional Indian motifs to the figure-hugging miniskirts and boob tubes of noughties club culture.

“My designs come from a very personal point of view; I felt that was a good place to start,” Lele reflects. “The visual codes of India are ones that we are all very familiar with—vivid hues and textile embellishments—and, beautiful as they are, I wanted to see something different.” Lele’s own taste is rooted in a minimalist aesthetic, with her personal style a mix of subcultural influences (“I wear a lot of leather but I don’t dress like a teenage goth anymore”) and clean, stripped-back lines. Contrasting colours and sheer fabrics are twisted together to create dramatic shapes, with a particular fondness for high-slit skirts and stretch-flared trousers.

“I wanted a representation of myself and other people where we really appreciate our culture but it’s not entirely us”

Lele channels her own mixed identity in each collection, but it hasn’t always been so intuitive an approach. “I never really considered my identity as such when I was growing up,” she says. “Because when you’re from different ethnic backgrounds or growing up in different countries, you deny elements of your heritage in order to assimilate into another culture. You can end up getting a bit confused, and I never really engaged or tapped into the Indian side of me.” It wasn’t until she began an MA in womenswear at the Royal College of Art in London, following a stint studying architecture in Edinburgh, that she finally felt able to explore personal experiences that had previously felt irresolvable.

“I wanted a representation of myself and other people who feel like this, where you really appreciate your culture but it’s not entirely you,” she says. “How could I show people an interesting perspective of India that they hadn’t seen before?” The floral motifs of Madhya Pradesh, the Indian province where her father’s family is from, sit comfortably alongside the cheeky visible thongs (glimpsed in her latest collection) and keyhole cut-out halternecks. “I’ve always had this double aspect running parallel through my life and my upbringing,” she explains.

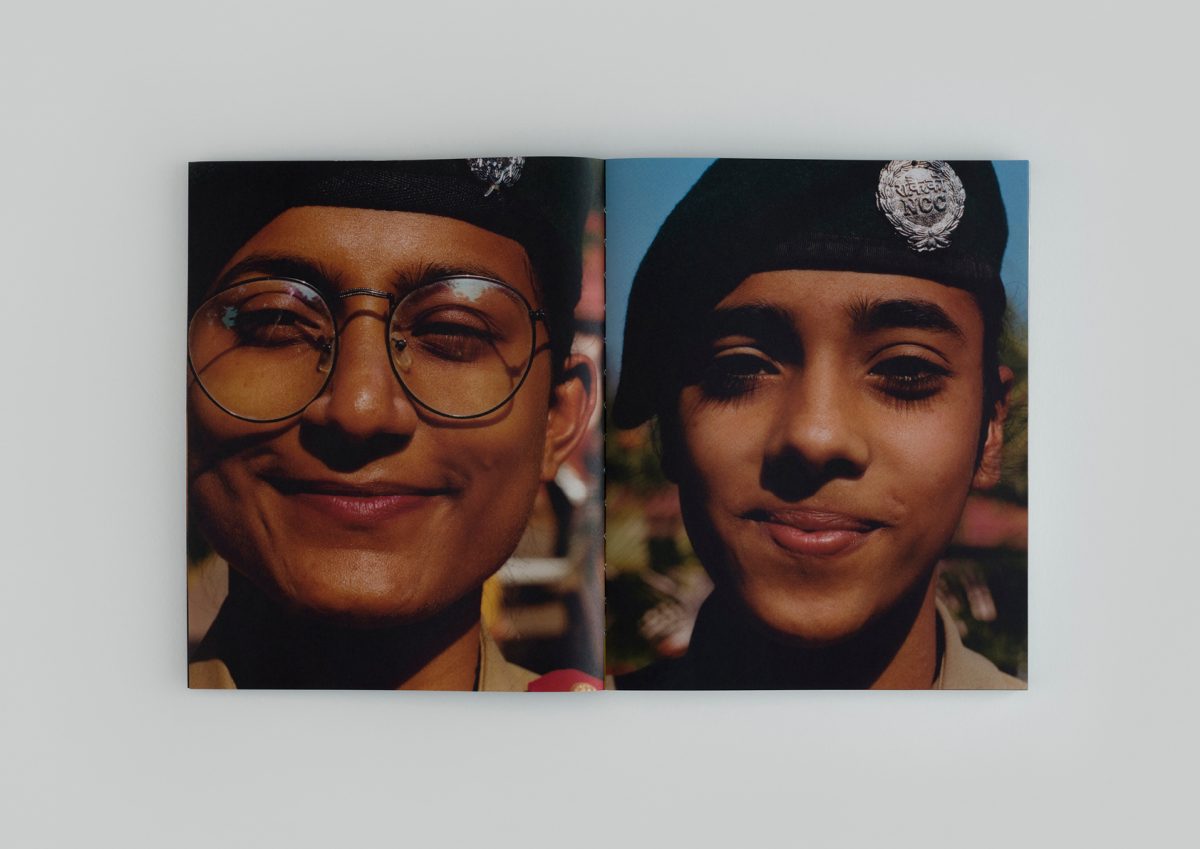

- Supriya Lele Spring/Summer 21 film stills

In careful designs characterised by drapes, twists and ties (a low-slung pair of trousers took more than two years to perfect), adaptability is paramount for Lele. Sizing is loose and can be adjusted by the wearer, while stretch fabrics are a favourite of the designer. “The sexiest clothes are the most comfortable,” she points out, “because if you feel comfortable, you feel confident and you look good.” Her mum has already picked out choice garments from Lele’s latest collection for herself, a testament to the accessibility of her outlook across the generations. “There’s nothing worse than wearing something that makes you feel inhibited, and the nice thing is that you can go to dinner in these dresses, sit down and eat a full meal.”

“I’m trying to show and propose a new interpretation of India. It’s about showcasing individual experiences”

Femininity is taken apart and refracted under Lele’s intuitive gaze, melding figure-hugging garments with a playful irreverence. Long leather coats skim the ankles while sheer high-neck and long-sleeved tops simultaneously hide and reveal. In Lele’s latest collection she introduced crochet for the first time as part of her interest in the sensual patterns that fabrics can create upon the skin, and that push-pull relationship with the unveiling and concealing of the female form. “We try to make sure that there’s a sensitivity to women’s bodies,” she says. A recent editorial shoot for L’Uomo Vogue saw Romeo Beckham photographed in a cut-off top designed by Lele, extending the fluidity inherent in her work beyond gender.

- Supriya Lele and Jamie Hawkesworth, Narmada, 2020

Lele attributes her quiet conviction in her own multifaceted taste to a youth spent with like-minded teens at gigs and illegal clubs in car parks in the Midlands. “I’d hang out with all the skaters and it was a really inclusive environment,” she says. “Especially as a person of colour and a minority in those environments, being part of the group gave me the confidence to be assertive about what I like and what I don’t, and to be very clear about what I identify with.” Those formative experiences are reflected in her nostalgic nods to her noughties teenage years, an era that has undergone popular revivalism in recent years, with today’s teens opting to wear styles influenced by Y2K icons from Britney Spears to Christina Aguilera.

Lele’s unwavering point of view has led to support from celebrities such as Dua Lipa and Rihanna alongside wide-ranging industry recognition. The designer was awarded a portion of the LVMH Prize in 2020, and she was nominated for the BFC/Vogue Designer Fashion Fund earlier this year. However her connection to her own family roots remains at the heart of her designs. Last year she journeyed to Jabalpur, a small city in central India overlooking the holy Narmada river, to document the place and its people. A collaboration with British photographer Jamie Hawkesworth, the pair immersed themselves in the local environment and shot Lele’s Spring/Summer 2020 collection. The resulting images were published in a beautiful hand-stitched book named Narmada, with all profits going to Girl Rising, a charity dedicated to fighting gender discrimination around the world.

“The sexiest clothes are the most comfortable. If you feel comfortable, you feel confident and you look good”

The designer’s connection to her heritage extends to the home-cooked food that her mum brings to her studio during busy periods, such as when they’re gearing up for Fashion Week. “She always makes amazing Indian food, which the whole team desperately looks forward to. She makes pakoras and samosas, curries and daals, and all sorts of stuff. She’s outstanding,” she enthuses. “Honestly, people say, ‘Oh my mum’s an amazing cook’, but my mum is an amazing Indian cook. Her curries are out of this world.” Lele herself enjoys cooking, and she explains that she also buys her team dinner once a week. “We’ll get burgers delivered to the studio and have a bottle of wine together. I love doing that.”

Lele continues to reflect upon her own complex relationship to heritage, using design as a tool with which to draw connections that are often hinted at rather than made explicit. The exquisite cut of a sari meets a riff on a band T-shirt under Lele’s watchful eye, where grown-up tailoring is shaken and given a moody teenage twist. Even as she continues to evolve through future collections, that youthful rebellion will inevitably remain, as will her enduring link to family. “I’m trying to show and propose a new interpretation of India. It’s about showcasing individual experiences. I’m trying to propose something new, and hoping that people will understand that point of view,” she concludes. “That’s it really, it’s very simple. I’m just trying to express myself.”

Supriya Lele’s Studio Recipe features in Elephant’s Spring-Summer 21 issue

Find the designer’s recipe for Roast Aubergine Curry inside the issue

BUY NOW