Despite making the first video installation to be bought by the Tate, SUSAN HILLER—an American long resident in the uk—says she has never quite felt ‘at home’ here. Likewise, her startling artistic investigations of the irrational and uncanny refuse to be domesticated or comfortably explained away. ‘If talking and thinking and working with ideas were enough,’ she tells SUE HUBBARD, ‘then why should we make art?’

THIS INTERVIEW ORIGINALLY APPEARED IN ISSUE 26.

‘And I reason at will, in the same way I dream, for reasoning is just another kind of dreaming.’

Fernando Pessoa, The Book of Disquiet

I first got to know Susan Hiller around 1999 when I included her work in my exhibition, Chora (co-curated with Simon Morley). Recently, when we met for lunch, after seeing her debut show at the Lisson Gallery, she told me how much of an outsider she continues to feel despite a major show at the Freud Museum, a retrospective at the Tate and recently joining this prestigious gallery. ‘For example, I’ve never been invited to join the RA’, she says over our green tea and satay. ‘Some of my students have, but I don’t fit. I’m not part of the establishment.’ With her multimedia practice of over 40 years, she is one of the most original and influential artists of her generation. But, perhaps, there’s some truth in her self-assessment. An American who has lived in London since the ’6os, she’s never felt quite ‘at home’ in her adopted country. ‘I’d never heard a woman called a cow before I came to England,’ she says, a phrase incorporated in her installation 008: Cowgirl from the Freud Museum, London (1992–94).

First trained as an anthropologist (a fact that, if given too much weight, annoys her), Hiller displays the intellectual rigour and curiosity of the academic, counterpointed with the ‘irrational’ explorations of the artist. Her work poses complex questions about identity, feminism, belief and the role of the artist. Never cynical or market-driven, it remains uncompromising, erudite and complex. The sort of art that forces you to think. She describes it as ‘a kind of archaeological investigation uncovering something to make a different kind of sense of it’, focusing ‘on what is unspoken, unacknowledged, unexplained and overlooked’. She explores what, to many, may seem irrational, sidelined and marginal aspects of human experience. She is interested in the traces we leave behind, be they the automatic writing generated in Sisters of Menon, a work made in the ’70s that investigates the permeable boundaries between conscious and unconscious utterance, or the investigations in Lucid Dreams (1982), where the presence or absence of her own face, photographed inside a photo booth, underlines the fragile nature of identity and the transience of existence like a series of grungy, do-it-yourself vanitas paintings. For the J Street Project (2000–05), she searched for every street sign she could find in Germany that included the word Juden (Jew). A chilling reminder that these are places from which whole populations and histories have been erased.

Her sources are eclectic, ranging from arcane texts and psychoanalysis, to popular culture. In her 2002 lecture at the Edinburgh College of Art, she quotes Freud who, in 1921, wrote: ‘It no longer seems possible to brush aside the study of so-called occult facts; of things which seem to vouchsafe the real existence of psychic forces… which reveal mental faculties, in which until now, we did not believe.’ Freud, she writes, claimed ‘that an uncritical belief in psychic powers was an attempt at compensation for what he poignantly called “the lost appeal of life on this earth” and that the problem with believers in the occult is that they want to establish new truths, rather than scientifically “take cognisance of undeniable problems” in the current definitions of reality’.

Her Lisson debut, which occupied both gallery spaces, interwove these tensions between the scientific and the rational with our desires and instinctual drives, in four ongoing themes: transformation, the unconscious, systems of belief, and the role of the artist as collector and curator. The presence of rare and unseen early works from the ’70s and ’80s underlined her interest in alchemy and psychological transformation. The 1970–84 Painting Blocks—made from cutting up and reassembling old paintings into sculptural ‘books’, labelled with the dates and dimensions of the original work—were shown alongside the small, ash-filled vials of Another (1986). Packed with the remnants of burnt paintings, these illustrate the reconfiguring of objects (or identities) in a transmuted form, one that echoes the theories of the psychoanalyst Melanie Klein on reparation and creativity.

Belief and the boundaries between the unconscious and the paranormal are examined in another work on show, Belshazzar’s Feast (1983–84), the first video installation ever to be bought by the Tate. As with much of Hiller’s work, the readings are fluid. This new bonfire version (which surely evokes notions of burning heretics and witches at the stake) is built from a stack of television sets that each frame a flickering orange flame. Accompanied by Hiller singing, whispered reports from people apparently seeing ghostly images on their TV screens, her young son’s reminiscences of the biblical story and Rembrandt’s painting of the same name, it creates a work that evokes primitive uncanny feelings.

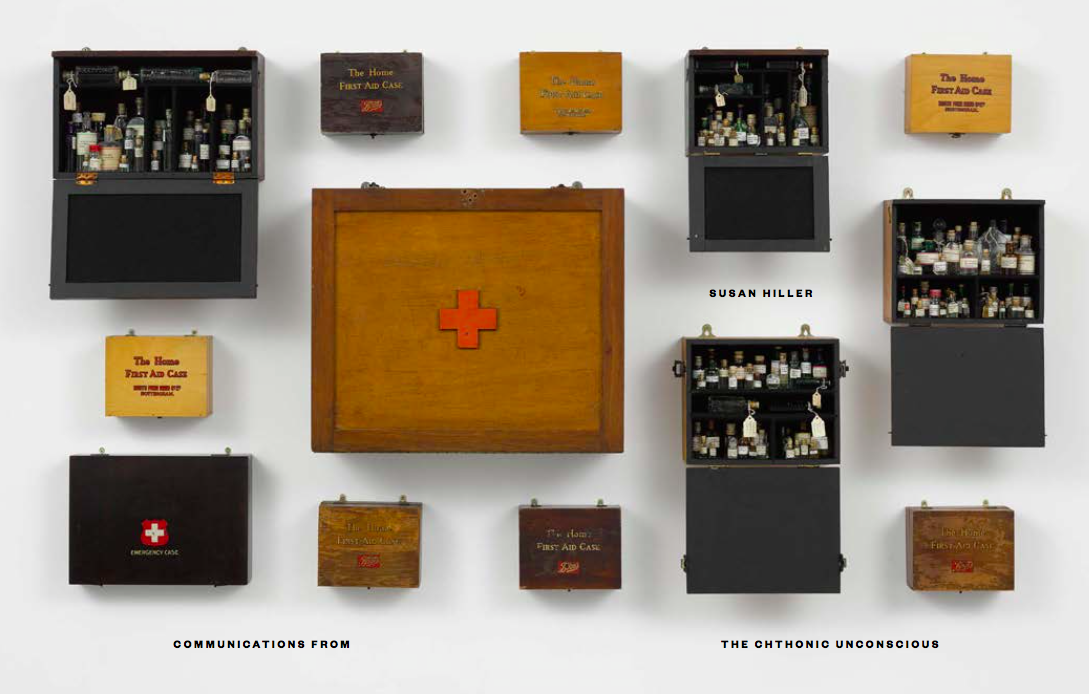

In her 2012 Emergency Case: Homage to Joseph Beuys—that quintessential shamanic artist—Hiller extends her investigations into faith, the irrational and reason. Vials of ‘holy’ water, from as far afield as the Ganges and an Irish sacred spring, allude to traditional beliefs, as well as to contemporary ‘alternative’ systems of healing. Clustered in reclaimed wooden cabinets picked up in antique markets, the installation is reminiscent of a medieval apothecary’s shop, as well as Damien Hirst’s medicine cabinets, suggesting that faith and reason are, to a large extent, cultural and historical.

It was in the eighteenth century that Carl Linnaeus devised a system of taxonomy, that branch of science concerned with classification which drew together species into rational groups and gave meaning to the modern world. This desire to define and categorize is inherent in A Longing to Be Modern (2003), an installation made up of 32 ceramic vases from the old East andWest Germany, along with 18 recycled cast bronze letters from gravestones, arranged on a kidney-shaped table in the gallery.

The role of curator and collector has long been part of Hiller’s practice. In the ’70s, a seminal work, Dedicated to the Unknown Artists (1972–76), consisting of a collection of over 300 postcards by unnamed artists, all bearing the words ‘Rough Sea’ and picturing stormy seas around the British coast, used the methodology, labelling and tabulation of a scientific research project. The investigations of this highly conceptual work have, more recently, been revisited in On the Edge (2015), a piece that presents 482 views of 219 locations along the coast of Britain where rough seas meet the land. Not only does this work tap into notions of English landscape and sea-scape painting, with its Romantic penchant for untamed nature and the sublime, but, in the use of ephemeral postcards, evokes that very British love of the untamed and unspoilt; that need to get away from the hurly-burly to become immersed in the authentic, raw and unmitigated. The phrase ‘on the edge’, of course, carries multiple readings—on the edge of sanity, of mainstream society, and of artistic or psychological breakthrough (or down). The relentless stormy tides battering this small island could easily be understood as the chthonic unconscious beating at the doors of reason or anarchy pommelling the gates of polite society.

Over lunch Susan Hiller is cautious about explaining too much about her work. ‘If talking and thinking and working with ideas were enough,’ she insists, ‘then why should we make art?’ She has no overarching authorial narrative and does not provide resolutions but simply offers the viewer a complex palimpsest of ideas. What is unique about her work is that her past anthropological studies help to frame a series of questions that are then translated through the sensibility and language of art.

A prodigious writer herself, Hiller is mindful of the possible interpretations, in our de-centred world, between the discourses of art, anthropology, religion and psychology. Her evocation of the work of Joseph Beuys seems to emphasize a belief that the traditional ways in which artists make and speak about their work are largely exhausted. She does not seek definitions or clarifications but rather reflects the ambiguities of the society in which we live. Like psychoanalysis, these are built on a chain of associations that are often slippery and fluid. ‘Truth’, a principal allegorical character in the discourse of modernism and humanism, has within this postmodern narrative been replaced by notions of relativity and legitimacy. Hiller refuses to pander to established tastes or prejudices but, to some extent, creates the audience she needs to respond to her work. Never nostalgic or self-consciously poetic, her archeological rummaging through the iconography of the past results in a series of investigations into the arbitrary and the marginal that run like fault lines though the contemporary world.