Elephant and Artsy have come together to present This Artwork Changed My Life, a creative collaboration that shares the stories of life-changing encounters with art. A new piece will be published every two weeks on both Elephant and Artsy. Together, our publications want to celebrate the personal and transformative power of art.

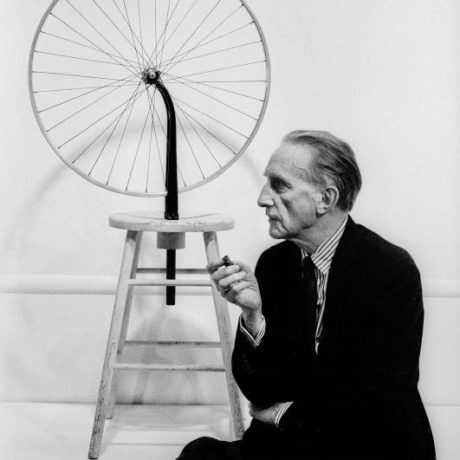

Out today on Artsy is Francis M. Naumann on Marcel Duchamp’s Bicycle Wheel.

A sensation of being crushed. An inability to breathe due to the invisible creature sitting on your chest. Jerking awake as you slap thousands of spiders away from your body. Running through the corridors of your secondary school chased by a nameless, unseen horror. A face appearing in the rear view mirror of your car as you drive along alone. Throughout my late teens and early twenties I frequently experienced some variation of these and other nightmares: not every night, but often enough that the anticipatory fear of them soon developed into chronic insomnia. Too scared to sleep in case an evil dream came, I spent night after night in a tense vigil, afraid even to relax my muscles in case something “bad” seized the opportunity to take me by surprise.

It was around this time that I started to become interested in dreams—and nightmares—as a subject in their own right. As a literature student, it didn’t take me long to come across, in a clumsy teenage way, Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams.

With no understanding of what psychoanalysis was, I read—or tried to read—the book as a kind of manual: I read it like a GCSE Biology textbook. Although nightmares aren’t treated fully as a subject in their own right, for Freud they function along the same basic principle as dreams themselves: if all dreams are a form of wish fulfilment, then nightmares are their masochistic shadow.

Bad dreams are what happens when a powerful desire is turned in on itself and repressed. The mind, especially the highly-strung, narcissistic and anxious teenage mind I was interested in (my own) was suddenly revealed to me as a site of nascent and internal terrors. Unable to understand the finer points of psychoanalysis, I developed a heightened fear of my own subconscious, a sense of my sleeping self as the enemy within, and a near-obsessive need to fortify the division between the rational, normal hours of daylight experience and the evil panic of the night.

In 2011, the year I turned eighteen, Tate Britain staged a landmark retrospective of the artist Susan Hiller’s work. One of the most prolific conceptual artists of the twentieth century, Hiller defined her own practice as “paraconceptual”. Her work, which encompasses and complicates the boundaries between video installation, performance art, photography, and writing, pushes against “rational” and “scientific” categories of truth and fiction. Her refusal to acknowledge divisions between “real” and “false” experiences roots her work in the paranormal and the psychoanalytic.

For Hiller, the entire framework of reality is built on productively permeable foundations. For the teenage version of myself that went to see the Tate Britain exhibition in 2011, it was Hiller’s explicit engagement with the subconscious mind that drew me to her work. It was a strong enough pull to entice me to spend a day’s worth of earnings from my waitressing job, and get the train into the city from its furthest rural suburbs.

“I developed a heightened fear of my own subconscious, and a sense of my sleeping self as the enemy within”

Hiller’s From the Freud Museum (1991-1997) was the work I was most interested in: a display comprising of fifty archive boxes, filled with small and intriguing objects like herbs and holy water, originally installed at the Freud Museum in 1994. I was keen, too, to see her automatic writing, interested in anything that imposed some kind of order on the chaos of the psyche, but it was in another room—arguably one of the least visually exciting—that I realized what I had been looking for all along.

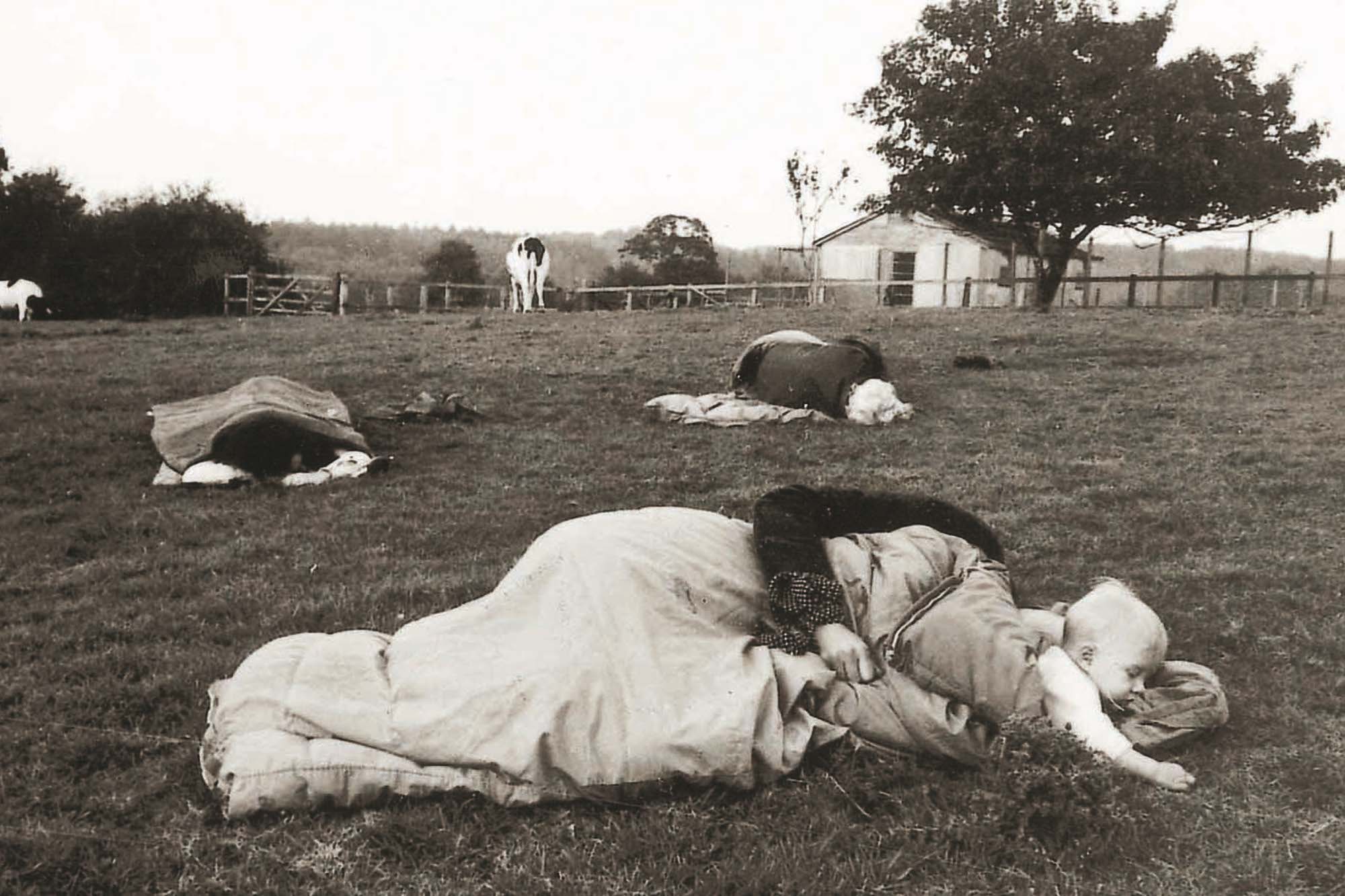

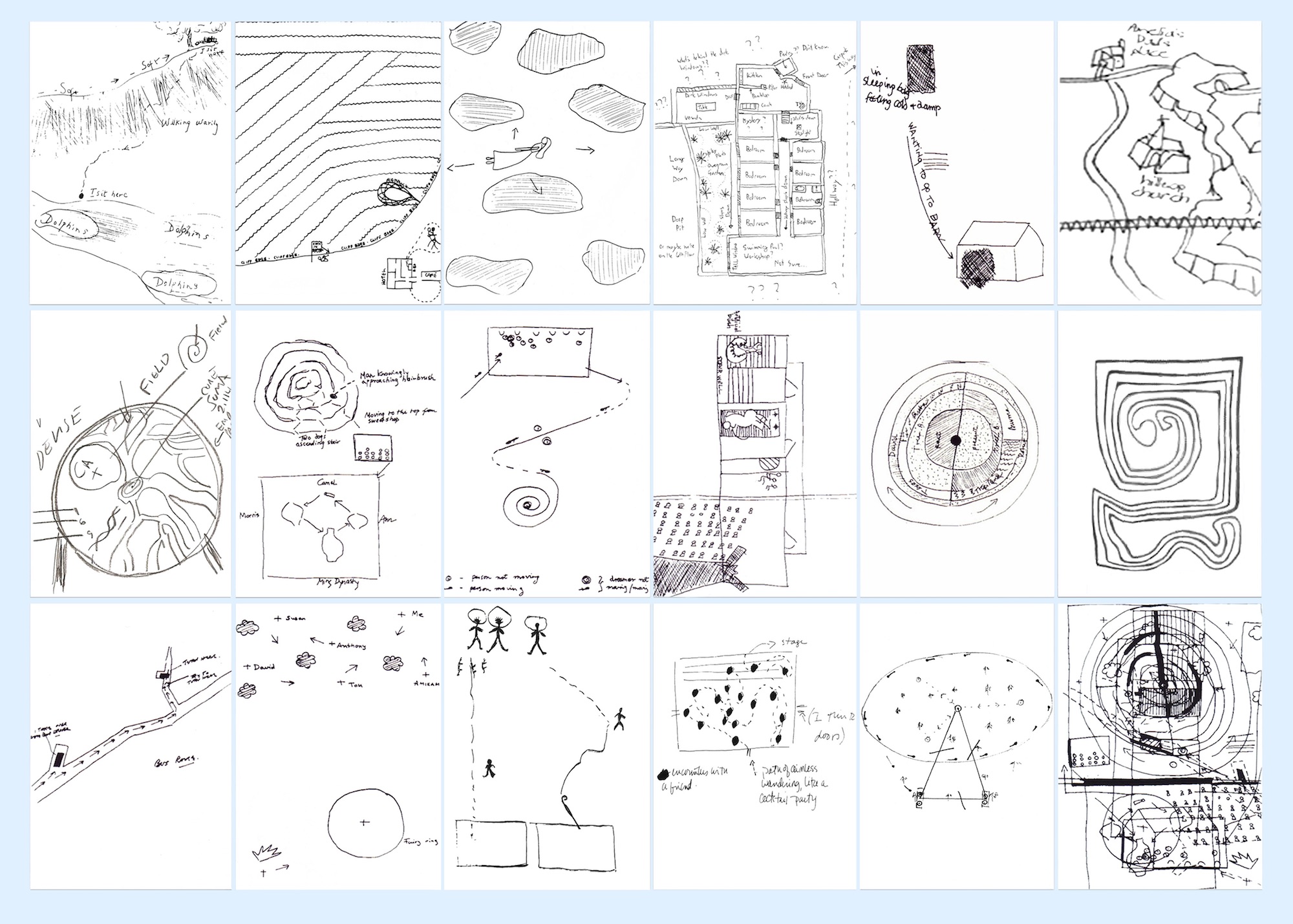

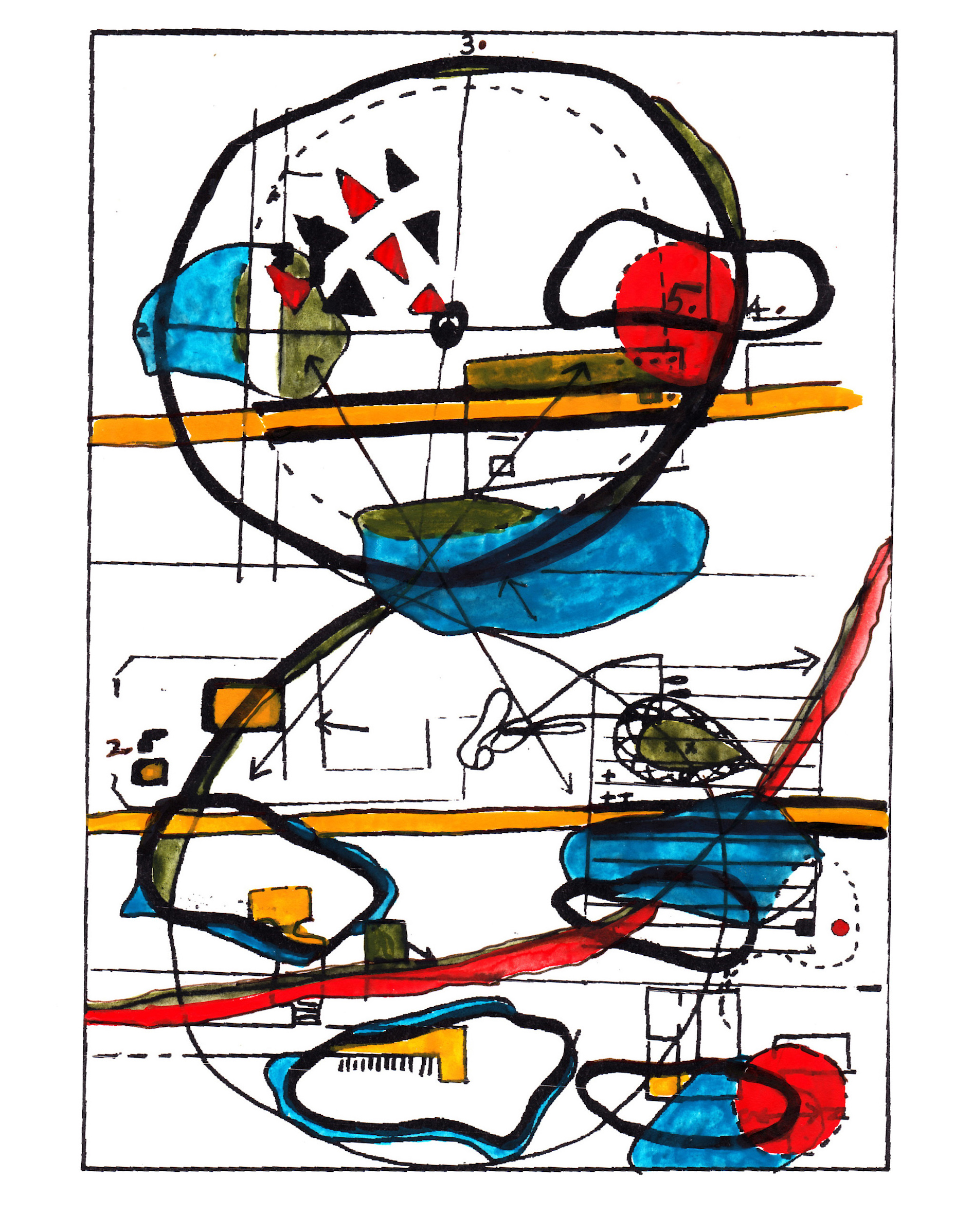

Dream Mapping (1974) came out of Hiller’s previous “group investigation”, The Dream Seminar (1973). Attendees of the seminar met weekly to discuss their dreams, a way of turning individual subconscious experiences into a collective project. The dream work of the following year was more ambitious: a cross between a performance, an event and an experiment. Seven dreamers slept for three August nights inside “fairy rings” made of Marasmius oreades (also known as “Scotch bonnet” mushrooms) that naturally occur in a field in Hampshire. The participants then recorded their dreams each morning in words, drawings and diagrams, which were later copied onto transparent paper and superimposed on each other, producing composite collective dream maps.

Fairy rings loom large in the folklore of Western Europe. Variously considered to be marks made by the dances of fairies, the rituals of witches, or the marks left by the Devil’s milk churn, to enter them is considered to be a dangerous game, and the courting of ill fortune. Although familiar with the fields that made up the landscape of my adolescence, and no stranger to camping holidays, the idea horrified me. Alone out there in the field, in dangerous nightmare territory (for what could be more conducive to a night terror than entering a fairy ring?), Hiller’s dreamers were exposed and vulnerable.

“Alone out there in the field, in dangerous nightmare territory, Hiller’s dreamers were exposed and vulnerable”

But, I realized, they were not alone. In fact, the project allowed for a way of being together even during sleep

. In those layers of tracing paper, the elements of each sleeper’s subconscious mind ceased to be an individual horror, a composite monster of repressed violence waiting to pounce, but one point on a map that led to another, a feature in common with another person’s experiences.

Susan Hiller didn’t really “teach me” how to sleep, and it wouldn’t be completely honest to pretend that I don’t still sometimes struggle with nightmares, with the kind of fear that encourages me to forget to turn the bedside light off, but these insomniac interludes are increasingly few and far between. Psychoanalysis deserves some credit, too. What Dream Mapping

did for me at eighteen, however, was show me that dreaming doesn’t have to be something associated entirely with private and individual experience. I learned that the mind is not a problem to be solved, and that collectivity is a mode of living that belongs to the night as well as the day.

Did an artwork change your life?

Artsy and Elephant are looking for new and experienced writers alike to share their own essays about one specific work of art that had a personal impact. If you’d like to contribute, send a 100-word synopsis of your story to office@elephant.art with the subject line “This Artwork Changed My Life.”

Head to Artsy to read their latest story in the series, a piece on Marcel Duchamp’s Bicycle Wheel.

READ NOW