Before Bankside Power Station became Tate Modern, a group of artists used the site to launch an explosive performance.

In Spring 1993, performance artist Anne Bean and percussionist Paul Burwell knocked on the window of the office at Bankside Power Station. They had just been commissioned by London International Festival of Theatre (LIFT) to create a celebratory performance for its tenth anniversary. Theirs was the ‘least bonkers idea’, say Rose Fenton and Lucy Neal, co-founding directors of LIFT.

Anne remembers two caretakers at the site ‘bored out of their heads’, who casually agreed to let them use the former power station as a stage for their performance. Inside the building she found the machinery – including the giant turbine that later gave the Turbine Hall its name – still in place: ‘It felt like the dying days of a dynamic fiefdom.’ The site had been practically derelict since it ceased production of oil-fired energy in 1981, but it was, Anne says, ‘utterly magnificent’. ‘We realised immediately that it had immense possibilities.’

Ansuman Biswas, a percussionist and interdisciplinary artist who collaborated with Anne and Paul on the performance, remembers Bankside as being ‘full of ghosts’. ‘It had that sense of beauty in dereliction. In something once powerful but now a decrepit shell of itself.’

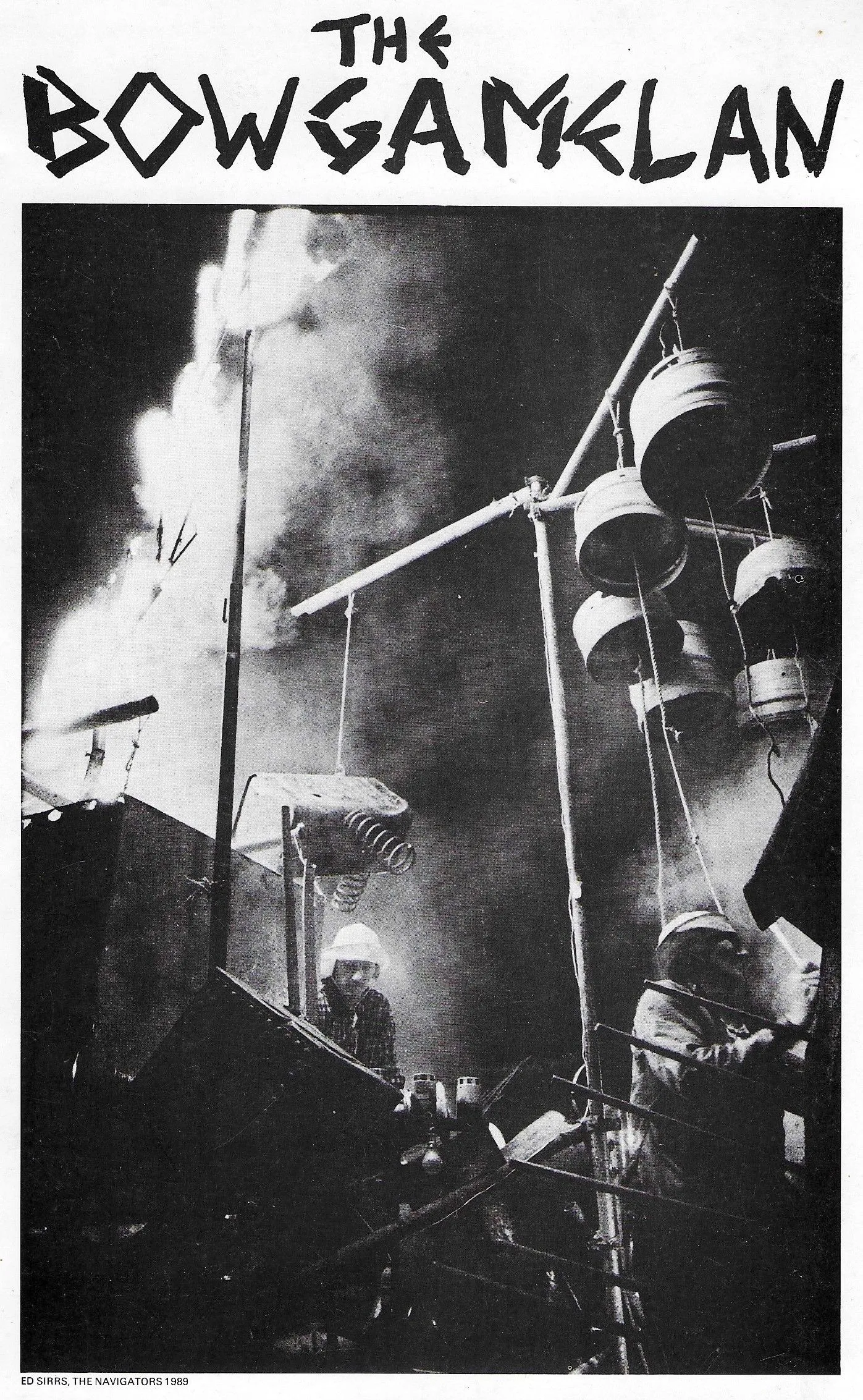

Another appealing trait was Bankside Power Station’s position beside the Thames. Anne, Paul and Richard Wilson, a sculptor, knew the river intimately. They had first met at artists’ studios at Butler’s Wharf, on the South Bank near Tower Bridge. Paul and Richard both had boats, and ‘out of curiosity’, explains Anne, the three of them explored the Thames and its smaller tributaries. During a boat trip up Bow Creek in 1983, the trio formed what became known as Bow Gamelan Ensemble, and their work quickly became associated with the river. In The Navigators 1989, for six weeks they lived and performed on a flotilla of barges that travelled around Bow Creek and into the Thames.

Ten years earlier, ‘Paul, Richard and I did an event under Tower Bridge with Paul’s rowing boat’, says Anne. ‘We had drum kits on the boat, and I swam in the Thames right under Tower Bridge’. The piece used dramatic lighting and sound effects, and played with echo and shadow. Eventually the Thames River Police came, sirens blaring, and shone their searchlight on Anne, casting an enormous shadow: ‘It was as if we’d arranged it’, she said. ‘We suddenly realised we could take on the city.’

When Bankside Power Station presented itself as the site for their next performance, Paul and Anne decided to create an urban, primal incantation to London. They invited Ansuman to compose a score for a group of 25 drummers. ‘It started with an instrument Paul had invented, which he called a daisy drum, which was also a sort of sculptural object’, Ansuman explains. Paul made them from oil drums, welding on drum hoops fitted with 22-inch Evans skins. ‘They were cheap and you could beat the hell out of them’, Ansuman says. On the other end of the drum, they fitted a ring of paper rope soaked in paraffin, to be lit during the performance. ‘When you hit the drum, a column of air would move through and throw out this huge flame. My job was to coordinate a group of drummers who were basically playing flamethrowers.’

On Sunday 13 June 1993, hundreds of guests travelled to a then obscure part of London. Richard Gray, who now works in Tate’s HR department, was there and recalls Bankside Power Station as ‘this slightly sinister building that I’d never heard of before. It felt like some hidden corner of London.’

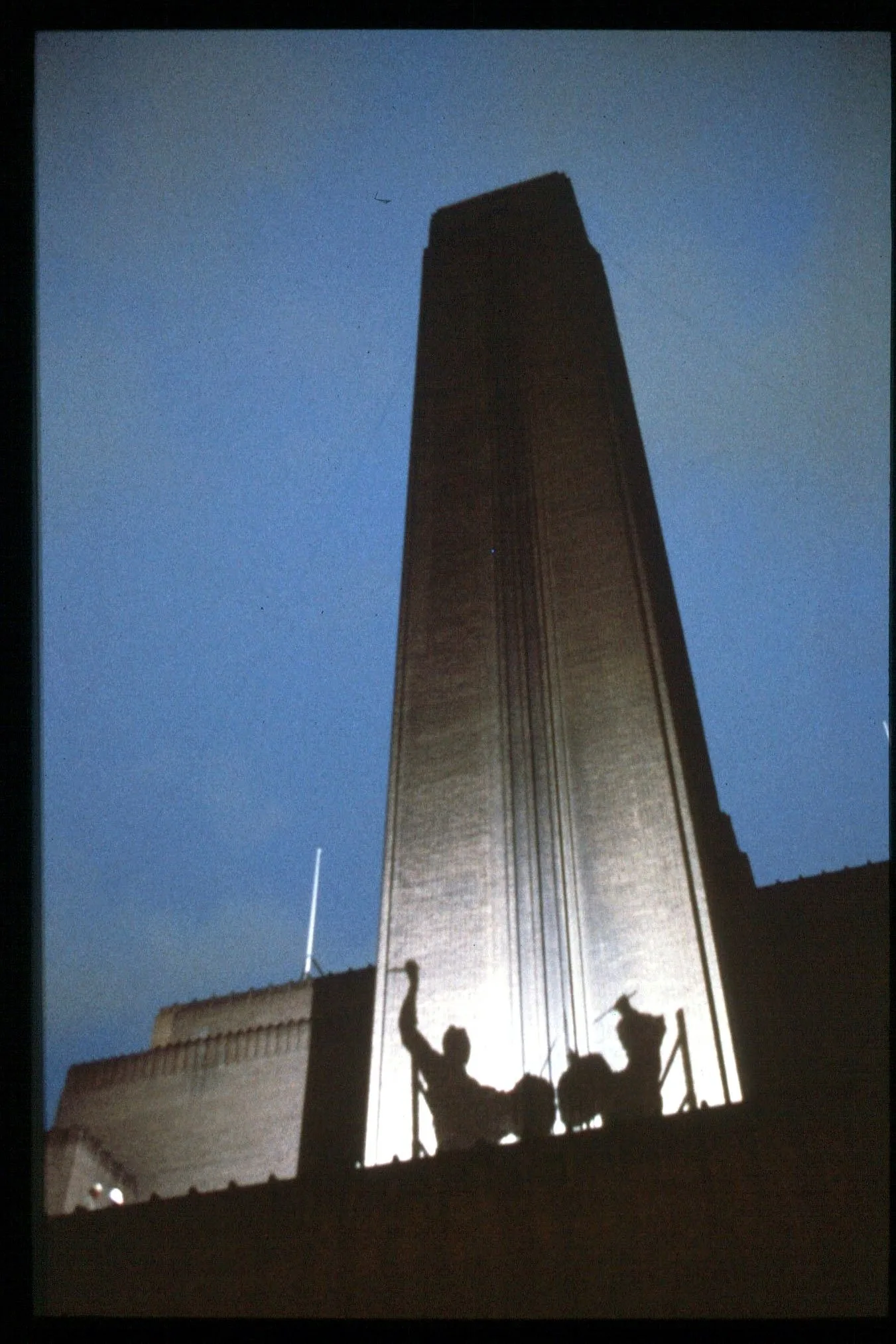

The 25 drummers were divided into four squadrons, placed high up across two levels of the building, bisected by the chimney. The daisy drums were fixed to the parapet, facing outwards so that the flames would shoot towards the river.

The performance started with patterns of drumming, radiating ‘left to right, backwards, forwards, upwards, downwards’, says Anne. It was ‘an extremely physically strenuous thing’, says Ansuman. He remembers being ‘drenched in sweat’ with ‘bleeding hands’. ‘It was like being in a battle.’

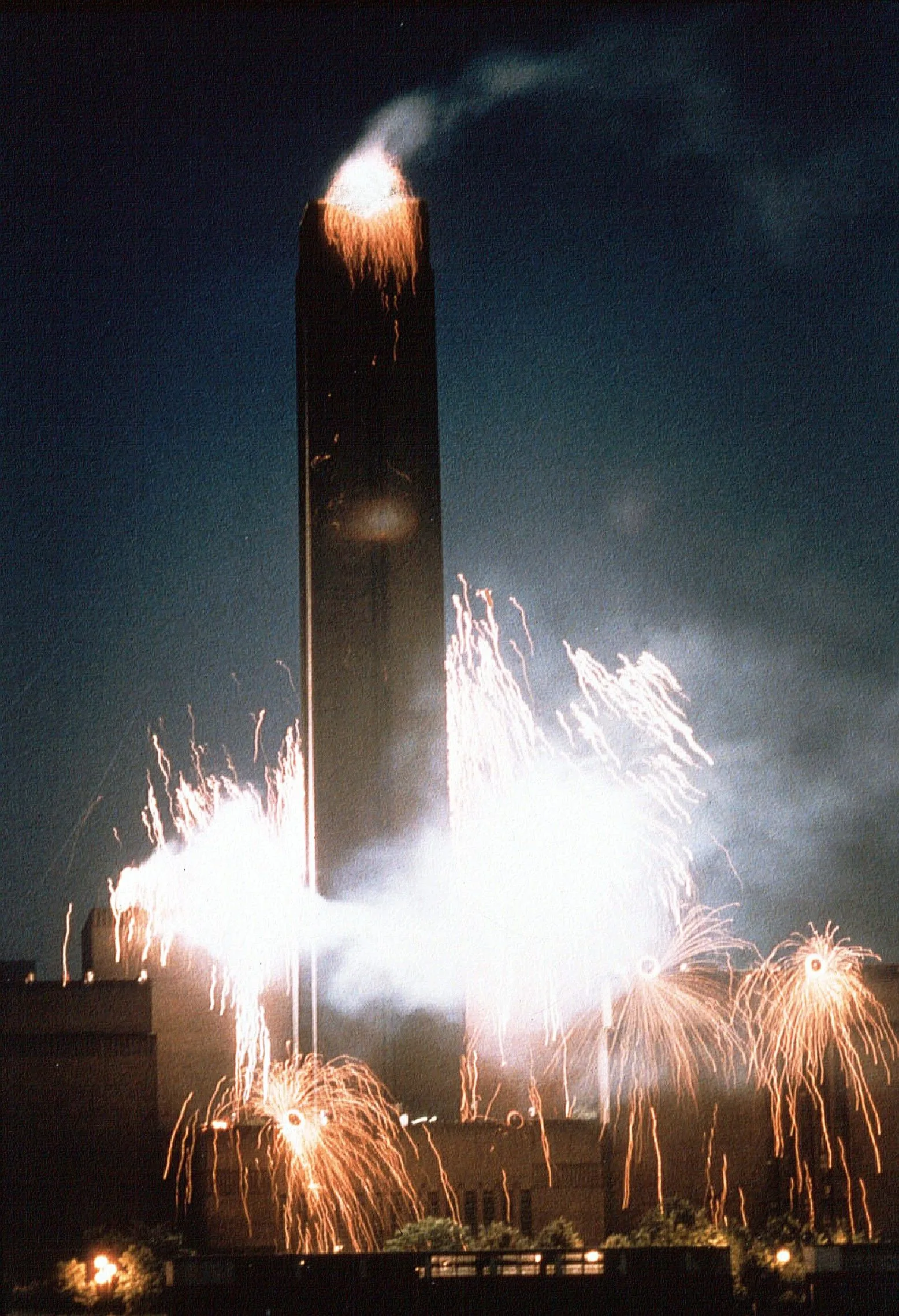

Alongside the fire drumming, a strobing flare cast a sharp shadow of Paul and fellow drummer Steve Noble onto the chimney, while Catherine wheels were set off from remote-controlled model helicopters. At one point, Paul set off a long string of Chinese firecrackers and Ansuman recalls that the sound literally flung him through the air: he would have been thrown off the parapet if Paul hadn’t somehow caught him. ‘That was the muscular power of the sound we were creating’.

Meanwhile, the helicopters lifted flaming paper ropes up into the sky, making a symmetrical curtain that framed the chimney. One of the helicopters dropped a rope – ‘a huge flaming python falling out of the sky’.

For the finale, a paraffin explosion was rigged inside the chimney. A 30-foot column of flame shot from it, like a colossal roman candle. ‘It was the biggest explosion I’d ever heard,’ says Ansuman. ‘We woke it up,’ said Lucy. Then there was silence, and slowly, in the far distance, the sound of sirens as the emergency services from all over London began to converge on Bankside. ‘We always called [the sirens] our coda,’ says Anne. ‘Paul’s attitude was to ask for forgiveness, not permission’, remembers Ansuman. Rose and Lucy recall ‘a party of serious-looking Chief Fire Officers’. ‘We told them that we were theatre artists; it wasn’t as bad as it looked.’ The organisers had, in fact, informed the police, warned local residents and invited the mayor.

The following morning, Dennis Stevenson, chair of Tate Gallery, called Rose and Lucy and asked for a photograph of the event. The gallery was looking for new premises for its ambitious new museum of international contemporary and modern art. In April 1994, Bankside was announced as home to the new Tate Modern.

Today, Anne looks out over the wide, grey expanse of Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall. ‘Paul and I had the catalytic sense that all that has happened, and will happen here is a continuation of our performance.’

A version of this article appeared in Tate Etc. Spring 2025, Issue 65.

Words by Figgy Guyver