A fashion show that is really an art installation and an exhibition that takes its cues from a spa: over three decades later, the artist is still finding new ways to subvert the world as we know it.

New York Fashion Week has come and gone. Whatever statements (or statement bags) that momentarily awashed our social media feed—and for some of us, our lives—are now, mostly, out of sight and out of mind unless your job is to eat and breathe trends. The best, or maybe just the most attention-grabbing, live on, of course, in a perpetual digital loop. But, for those who do not suffer from fashion fatigue, or better yet, those who were left unsatiated, wanting something more, then Sylvie Fleury’s exhibition “Just Jacuzzi” at Company Gallery in Manhattan is a splash of cold water, albeit the sartorial is more of a footnote than the main course.

It’s no secret that the fashion industry is in the business of selling products, and the theatrics, artistry, and fanfare—no matter how effective or ingenious—will always be, to some degree, in service of the primary maxim: to get people to buy, buy, buy. For art, the same ethos is more of an ugly, open secret, despite the fact of the matter being that—contrary to the dated yet romanticised notion of the starving artist making art for art’s sake—artists need to sell their work to survive (unless they are part of the lucky trust fund class that seems to be engulfing its less fortunate artist peers). However, as we all know, selling doesn’t stop—or even really start—with the artist. Rather, it gains value and trades hands on the secondary market where, at its best, it is an indicator of an artist’s rising star and, at its worst, it is a way for the rich to get richer and protect their assets.

The fetishisation of art and how it relates to the commercialisation of glamour and luxury (and the way these are gendered and packaged to female audiences) are tropes that Fleury has been subverting since her early works in the late ’80s. For the artist, tried-and-true symbols associated with fashion, pop culture, and art history offer new ways to think about over-consumption, hyper-individuality versus herd mentality, pervasive sexism, and all of the other existential-crisis-inducing symptoms of late-stage capitalism.

At Company’s opening night, the gallery is a runway. A pastel, spiral-like orb painted on the back wall sets the scene, and chairs, two rows deep, flank the catwalk’s narrow perimeter. In the audience, I spot the designer-duo behind the cult-favourite label Women’s History Museum and artists Jonathan Lyndon Chase and Jeanette Mundt, among other creatives from the Company universe. Club-ready chopped and screwed-electronic music thumps as women in slicked-back buns and smokey eyes strut down the runway in unassuming, black jumpsuit uniforms. Models include familiar names such as artists Cajsa von Zeipel, Gisela McDaniel, MarieVic, model Imani Randolph, and designer Claire Sullivan.

It quickly becomes clear that Fleury is not a fashion designer, and the clothes are not the focus. Instead, Jackson Pollock-esque gold and silver paint-splattered black canvases drape from chains like purses on the model’s arms. Each woman exits the stage and walks with precision to the lone screws that dot the gallery walls; they hang up paintings until they overlap, and, at last, the gallery is filled. After the final artwork assumes its rightful place and models tuck away backstage, Fleury herself makes the customary finale bow on the runway, dressed in straight-leg jeans, white-heeled boots, and a black, long-sleeve turtleneck with large, architectural shoulder pads. She beams happily at the crowd, waves, and then turns to exit, her layered, shoulder-length sandy blonde hair disappearing behind the arched entryway.

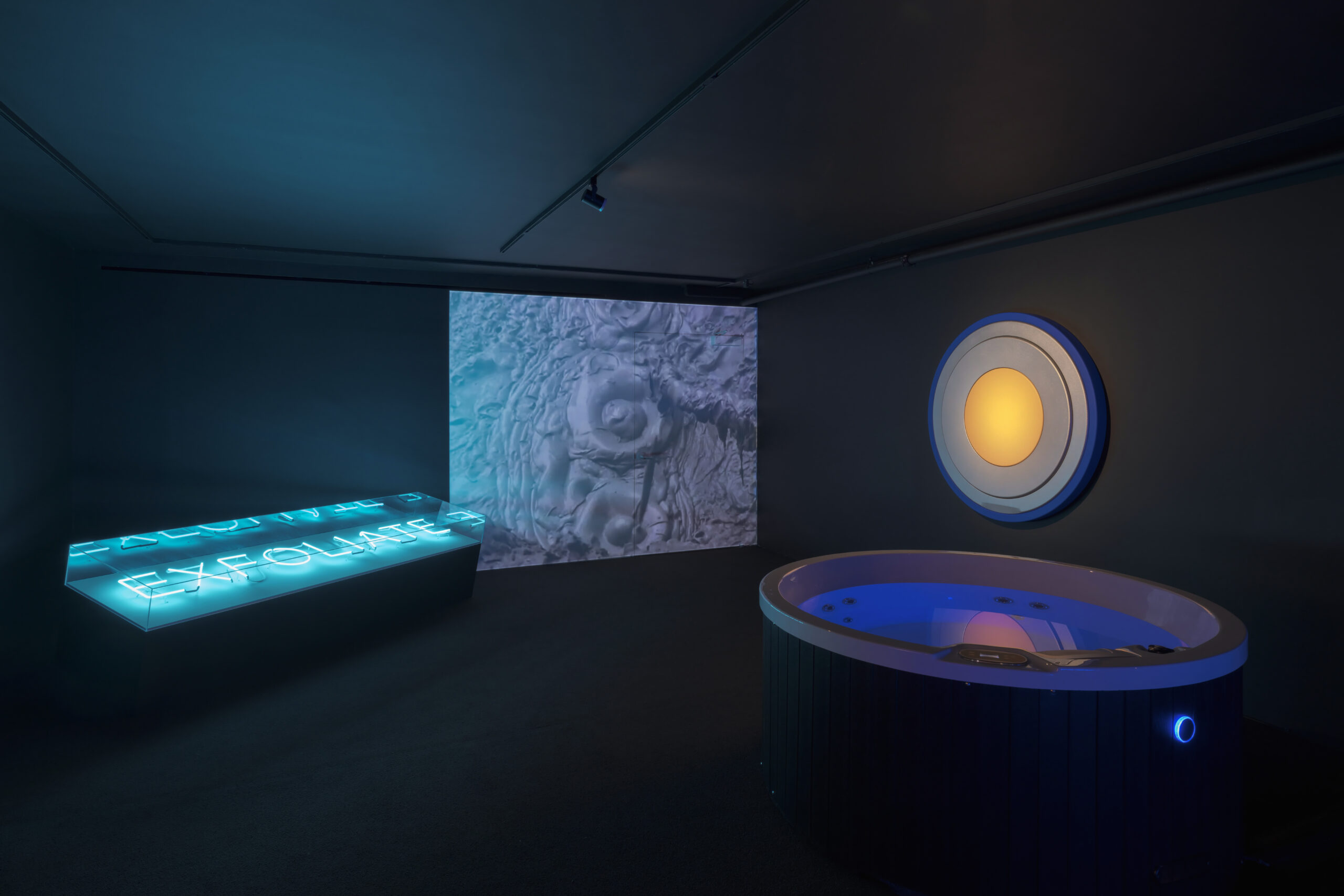

Following the show, visitors trickle down to the backspace that leads downstairs. The small room radiates soft blue light (or pink, depending on the angle). A sleek, phallic white rocketship towers in the middle of the room near a white-robed mannequin with “Just Jacuzzi” emblazoned on it. On the lower level, a torso and legs clothed in a Courrèges mini skirt poke out of the wall. In Rotorua Perpetual Glow Machine, 2001/2022, a hot tub bubbles and glows slime-green against a video of sputtering mud projected on the back wall. Abstract, portal-like sculptural paintings that resemble makeup compacts hang on the walls. Words glow from a vitrine: “exfoliate.” In the gallery’s back room, amidst changing models and friends eating thin-crust slices of veggie pizza, Fleury seems relaxed, pleased that the event went off without a hitch. “The music was great, the catwalk was great, clothes great, hair great…I couldn’t find anything to make myself suffer over,” she deadpans, framed by one of her new furry works, aptly titled Cuddly Painting (Blush Pink), 2024.

The artist is no stranger to creating a spectacle that packs a punch: from her ’90s all-women motorcycle club entitled She-Devils on Wheels to her infamous 2008 film Cristal Custom Commando, in which close-up frames depict three leather-clad She-Devils armed with machine guns, shooting at Chanel handbags hanging from targets. Fleury’s work has long challenged the toxic masculinity and skewed power dynamics pervasive in culture. In the mid-’90s, for a group show at a German museum, she scattered high heels atop a metallic, minimal floor piece by Carl Andre, who, upon catching on, furiously demanded her work be removed. At Salon 94 in 2013, she restaged the intervention with a catwalk-like floor reminiscent of Andre’s piece, along with patent-leather stilettos that viewers could try on.

Fleury is no stranger to referencing herself. Throughout her practice, time doubles over and collapses, underscoring how little has changed: there is still a $192 billion dollar gender gap in the art world. A scene from her original 2008 art-as-fashion-show at Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac comes to life in her 24 January recreation. If she is trying to shock or make a statement that hasn’t already been said, then it would be considered a failure. But if it were, rather, as it reads to those familiar with her work, a commentary on the redundancy of aesthetics in a post-shock world, where nothing novel is left, and the only thing left to do is to rework the old to new ends, then it is surely a success.

The Swiss artist’s concurrent solo show at Sprüth Magers Window in Berlin, which opened last week, is a sparser, more pointed companion to her New York exhibition: The French word égoïste (egoistic) appears across 13 bright neon works on the walls, a riff on the lettering of the namesake Chanel fragrance and one of the earliest logos that the artist reappropriated in her works.

Decades later, Fleury’s approach still hits. The spa exhibition is immersive—hovering between eerily familiar and uncanny—and fresh in its re-imagining of the everyday, commercial throes of modernity. When considered with the runway-cum-installation, the overall result is less jolting than it presumably was the first time around. This isn’t as much a revelation about how shock has become so pervasive that it has lost its edge (although it’s not not that, too), but rather a case for the enduring influence of Fleury’s brand of subversion. She first staged her jacuzzi in 2001, and in the last decade, artists including Tita Cicognani, Juliane Hundertmark, Mika Tajima, Cindy Baker and Ruth Cuthand have all used hot tubs as art pieces. For Fleury, the object has always been a by-product of the messaging. This framework is reinforced at Company, where materialism begets meaning.

Written by Meka Boyle