Under the Influence invites artists to discuss a work that has had a profound impact on their practice. In this edition, painter and sculptor Tae Kim reflects on the impact that Korean paintings from the Joseon Dynasty have had on her Faceless Gamer works, which set out to capture something far beyond the physical

I’ve been making replica Joseon Dynasty paintings for museums for more than ten years, using the exact techniques and materials of the originals. It has given me the privilege of watching a painting be dismantled for reconstruction and conditioning, including at institutions like the British Museum. This experience helped me when thinking about the new works in my series Faceless Gamers.

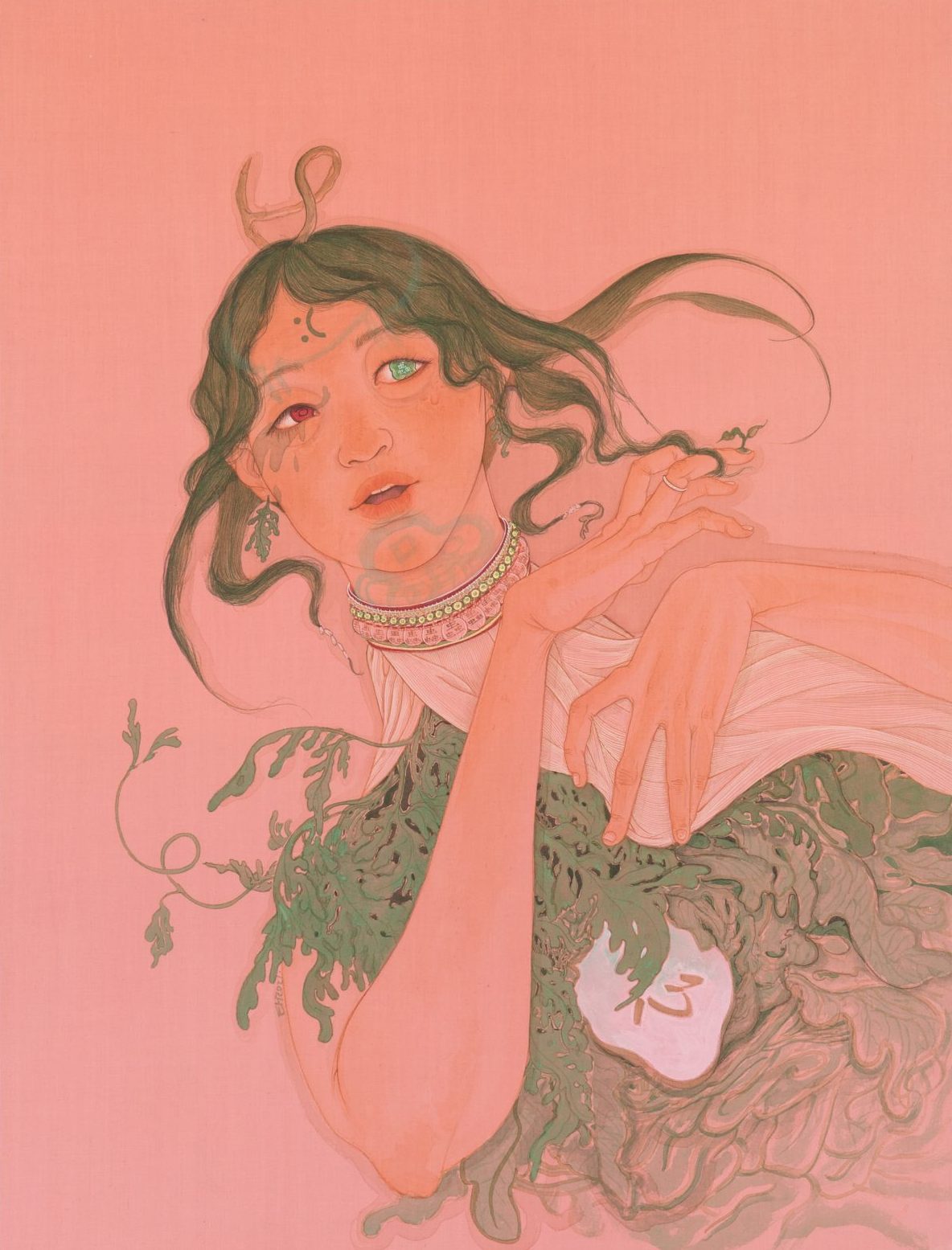

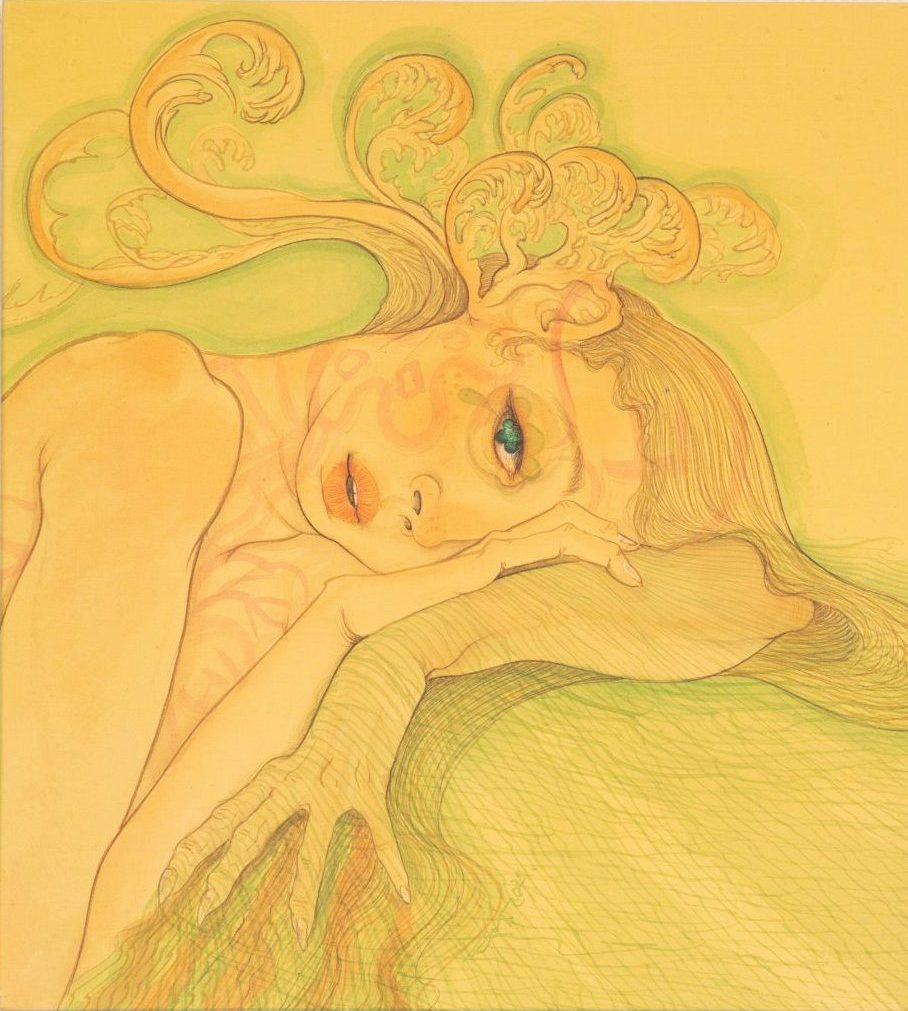

Joseon Dynasty portraiture is all about trying to make a very flesh-like face. The reverse-painting method looks very different from the back because you’re using the silk’s transparency. You don’t have too much pigment on the top.

In the anonymous work above, his clothing is very pigmented as it’s on top of the silk. Whereas if you look at the faces, the pigment is on the reverse side of the material. You can use the depth of the silk’s very thin membrane. That’s the beauty of what I feel when I want to capture a person’s flesh.

These works were produced by a government system, so you’d have many people working on a single painting. I am trying to think about the new ways that people are connecting in the internet world, and so I return to this Joseon Dynasty portrait. Physical appearance doesn’t mean anything, and yet we have flesh and bodies that we are bound to.

My sole goal in terms of painting the faceless gamers is that I want to somehow possess them. I want to incorporate my own information and experiences into them. In terms of gaming, there are two things that stand out for me. You’re in a beautiful world where physical restrictions are gone, a total cyberspace. And you can upload and customise your own character.

“I am trying to think about the new ways that people are connecting in the internet world, and so I return to this Joseon Dynasty portrait”

Most of the games that I’m interested in are multiplayer online role-playing games, not console or story games. These games are all systematically meant for people to fight amongst each other. We are doing what we learned while we were growing up. That for me is a human limitation. These kinds of limitations become physical in my paintings. I depict skin marks, wrinkles, or sometimes tears, in my characters. I deploy irony when reminding viewers that these creations have real-world relations. That’s the social aspect that I’m thinking about.

I’ve always been interested in portraiture. My way of painting a person before 2018 was all about actual physical appearance. I was trying to both mimic the lines and suggest the impossibility of being able to mimic the lines. Now, even though I’m painting only semi-figuratively, I want to be honest about the relationships that I find online and depict in my work.

“Chinese and Japanese portraiture commodify or beautify a person. Korean portraiture is all about reality, the act of being plain and honest”

If you look at the face in this painting, there is a moon-shaped scar that makes him look very badass. Chinese and Japanese portraiture typically either commodify or beautify a person that they want to depict. Korean portraiture is all about reality, the act of being very plain and honest. I always try and achieve that feeling of reality in my works.

I am more interested in the soul as comprising multiple, diverse personae. With Faceless Gamers, I am working in a culture where I don’t need to see a person’s physical appearance anymore. But at the same time, precisely because I don’t know their physical appearance, I have a deeper connection to them. I’ve grown up with that experience through gaming.

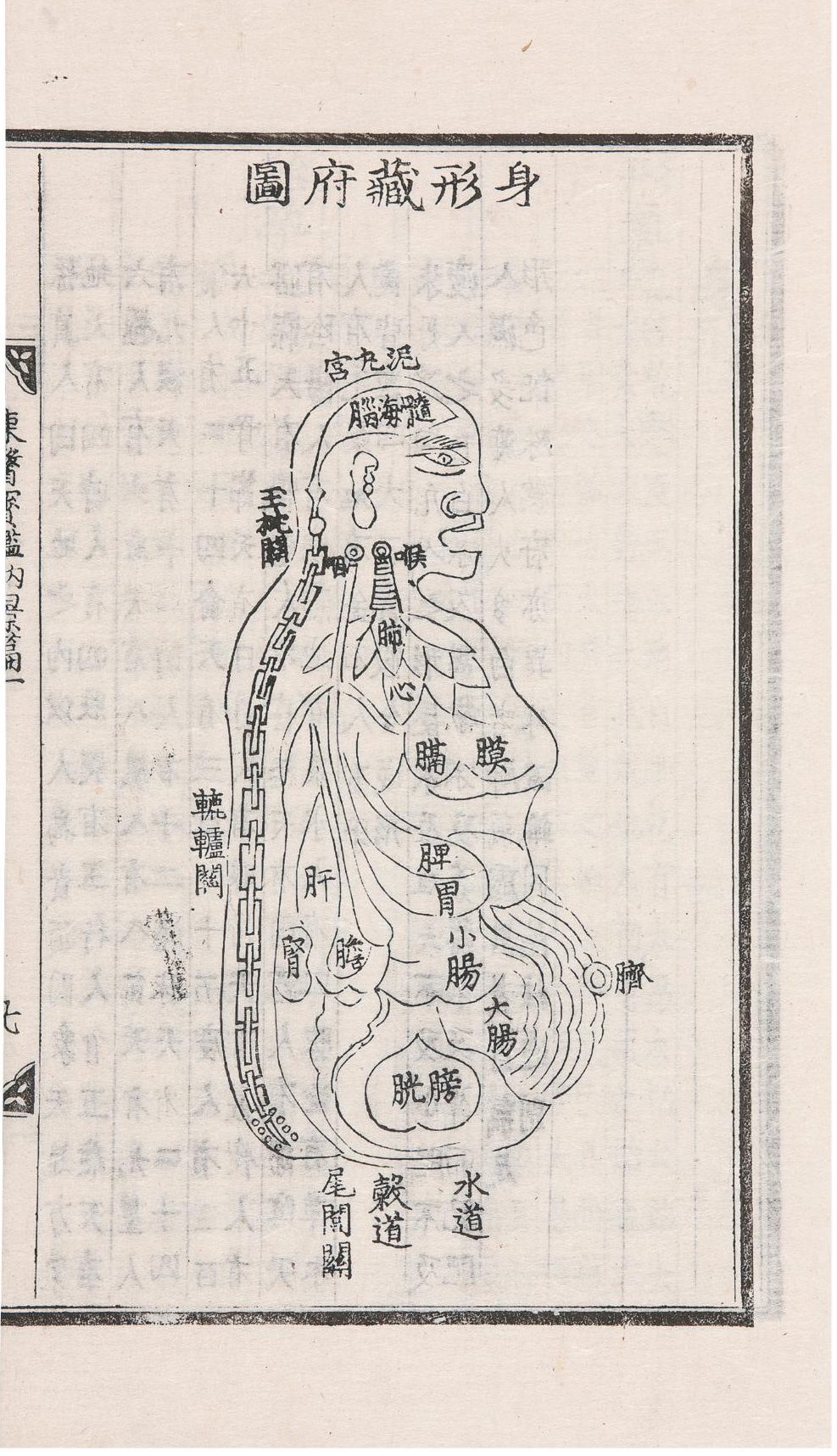

In East Asia, we have this idea of people being a smaller version of the universe. If you open a person up after they’ve died, the energy is cut. Whereas in each living person, there is an internal energy structure. That energy has a flow, and mostly people believe that the centre is in the heart.

In my portraiture, I give each subject their own newly transhumanistic organs, in order to cope with someone who is in between the internet and physical realms. All the links and connections that comprise us are detailed in these organs, and each one is different.

As told to Ravi Ghosh, Elephant’s editorial assistant

Tae Kim, Faceless Gamers, Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery (Wandsworth), London, until 30 April

Kim images © BJ Deakin Photography

Under the Influence

Discover the connections between today’s creatives and the artists who affected their work

READ MORE