Ahead of the Met Gala this evening, Elodie Saint-Louis looks at key art historical references representing the Black dandy.

Style, French philosopher Roland Barthes once wrote, “makes a difficult action into a graceful gesture, introduces a rhythm into fatality.” Style is “to be courageous without disorder, to give necessity to the appearance of freedom.”

The dandy, utterly devoted to his whims and committed to self-invention, is style personified. The dandy knows it’s not about the clothes themselves but how one wears them. Knows that distinction lies in being distinguished.

The dress code for this year’s Met Gala is “Tailored for You,” a reference to the dandy’s characteristic preference for suits and menswear. This year’s Gala, in conjunction with the Met’s exhibition Superfine: Tailoring Black Style, celebrates dandyism and its influence on Black style. Slaves to Fashion: Black Dandyism and the Styling of Black Diasporic Identity, by Professor Monica Miller of Barnard College, inspired the exhibition. In Slaves to Fashion Miller describes dandies as “self-styling subjects who use immaculate clothing, arch wit, and pointed gesture to announce their often controversial presence.” The Black dandy abounds in fashion, art, music, and film, from Andre Leon Talley, John Shaft, and Andre 3000, to Little Richard, Cab Calloway, and Janelle Monae.

The history of the Black dandy begins with the advent of the slave trade. Europeans, Miller writes, kept African boys as “entertainment, curiosities, and sometimes surrogate sons.” These young men became a mixture of servants and pets parodied and paraded as status symbols. Many of these boys were immortalized on canvas in aristocratic portraits, props there to contrast and represent the wealth of their “superior” white counterparts. So the Black man, the slave dressed in fine clothing, became a point of humor and irony. Cue a bevy of stereotypes like Dandy Jim and Long Tail Blue.

In the United States, Black dandyism developed via the “occasionally dressed-up and highly visible common laborers, domestics, and unskilled workers in the free, urban underclass,” states Miller. One’s look became a way to assert one’s dignity. A suit wasn’t just a suit; it represented freedom, possibility, and power, an affirmation of one’s individuality. Abolitionist Frederick Douglass and sociologist W.E.B. Du Bois were early dandies known for their refined and winsome appearances.

The fight for liberation in America connected to a desire to be seen as fully human. Part of that fight necessitated creating new images of Black people, created by themselves and on their own terms. The Harlem Renaissance, a byproduct of the Great Migration, and the Black Arts Movement, which emerged out of the Black Power and Civil Rights Movements, led to a flourishing of Black creative output and energy. The Black dandy appears throughout both, an ever-present fixture in the Black artist’s imagination.

In honor of this year’s Met Gala, below are essential works of Black dandyism throughout art history:

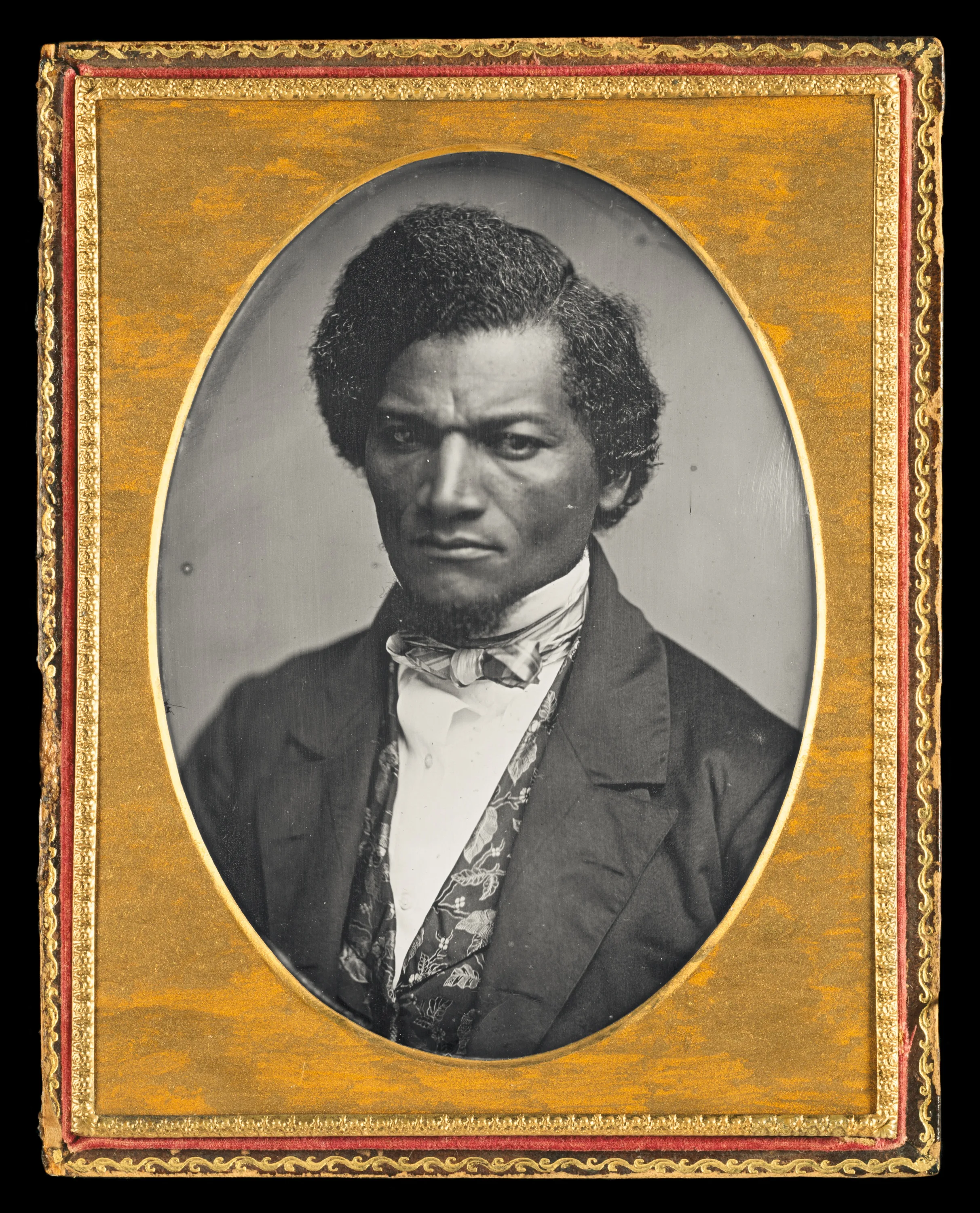

Frederick Douglass, 1847-52, Samuel J. Miller

The most photographed man in America in the 19th century, abolitionist Frederick Douglass understood the significance of images; this portrait of his, a daguerreotype taken by Samuel J. Miller, became part of his strategy to abolish strategy. Douglass, dressed finely in a patterned waistcoat and bowtie, stares directly at the camera, his gaze solemn, the utter opposite of a Dandy Jim.

Diary of a Victorian Dandy: 19:00 hours, 1998, Yinka Shonibare

In his playful photographic suite Diary of a Victorian Dandy, artist Yinka Shonibare engages directly with the tradition of the English dandy by inserting himself into the role. Shonibare, playing an entitled aristocrat, lounges and waits to be served by his white waitstaff. Shonibare parodies quintessential dandy Oscar Wilde in his other equally theatrical series Dorian Gray, in which he plays the novel’s titular character.

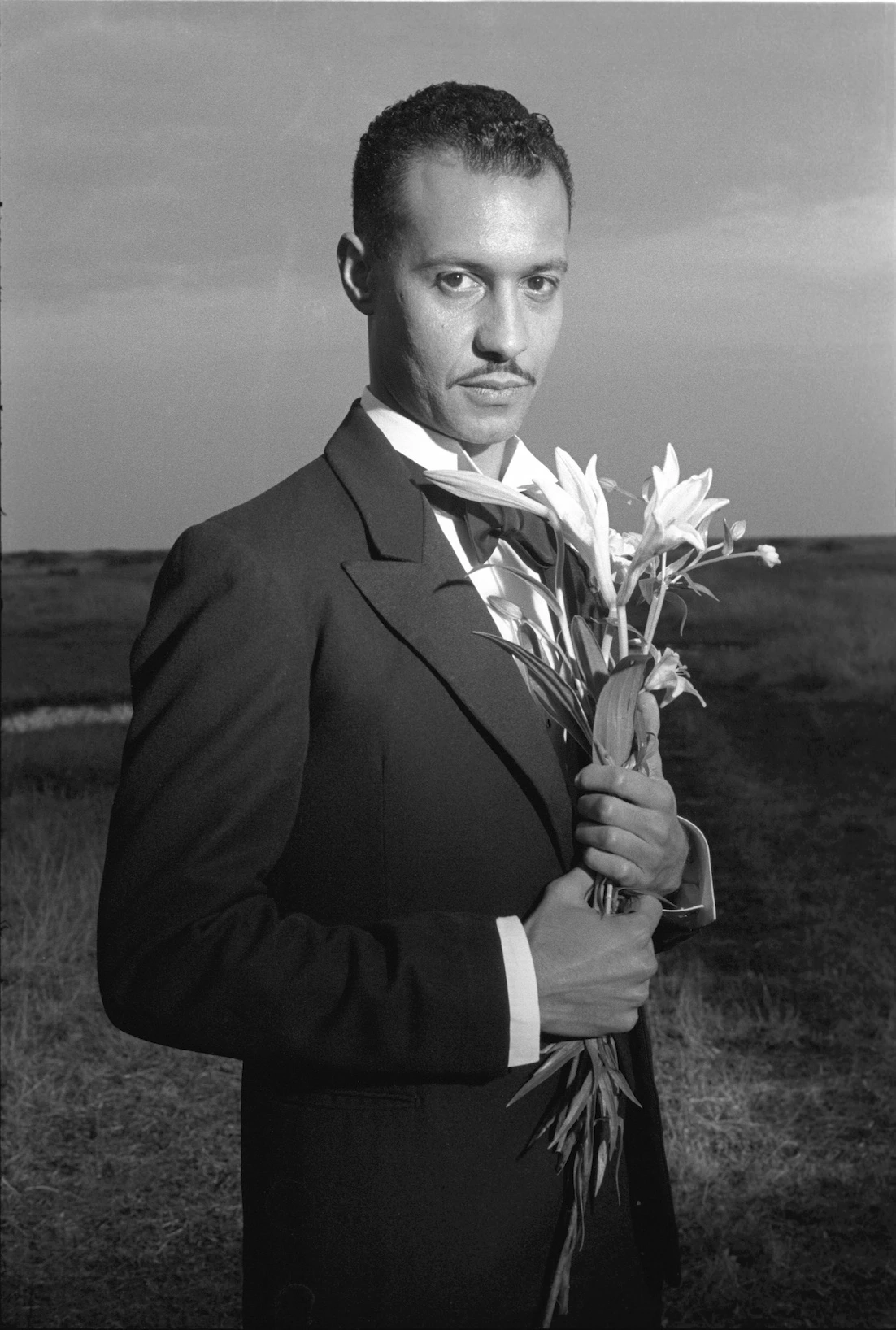

Looking for Langston (Looking for Langston Vintage Series), 1989/2016, Isaac Julien

British filmmaker and artist reimagines the life of poet Langston Hughes in his film Looking for Langston. The film, opulent and brooding, delights in the pleasures of the body.

Street Life, Harlem, 1939-40, William H. Johnson

A hip couple—two dandies out on the town—stand amidst a vibrant Harlem. They take up as much space on the canvas as the buildings behind them. They’re integral to the city, part of its atmosphere and rhythm. The dandy is always a cosmopolitan, a flâneur.

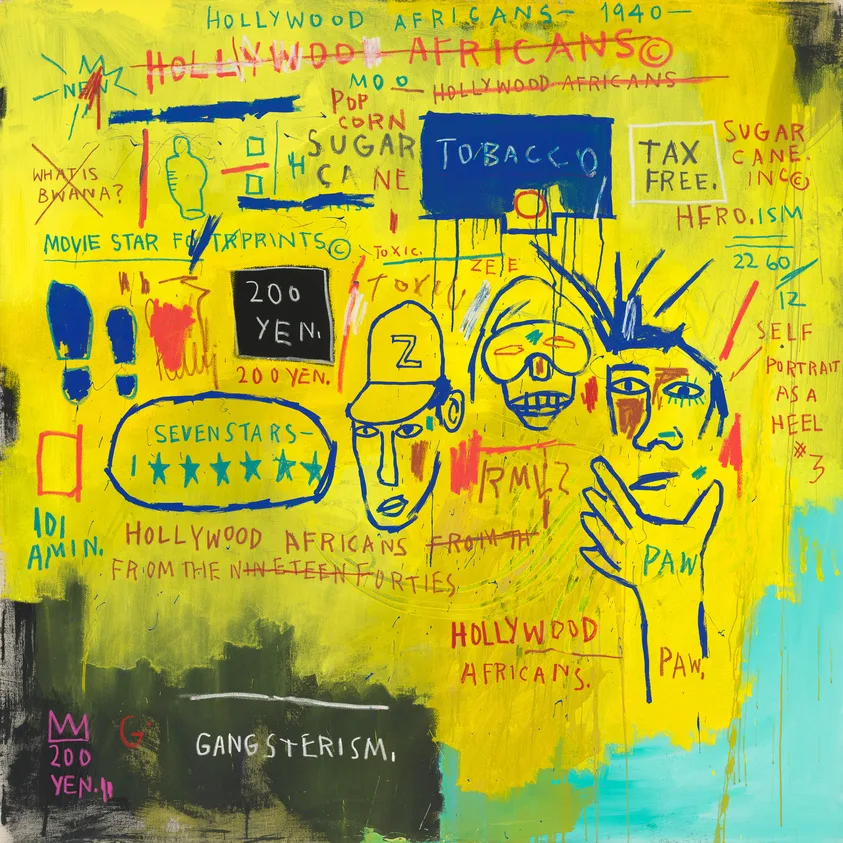

Hollywood Africans, 1983, Jean-Michel Basquiat

A provocateur with a signature look, painter Jean-Michel Basquiat was the ultimate dandy. Extremely fashionable, style played a critical role in his persona; he would trade canvases for clothes and modeled for Comme des Garçons. Basquiat’s suits—he was a fan of Armani—would end up paint-splattered, as he wore them in the studio. In Hollywood Africans, Basquiat alludes to the systemic racism found in Hollywood and the limiting stereotypes Black artists have been subjected to.

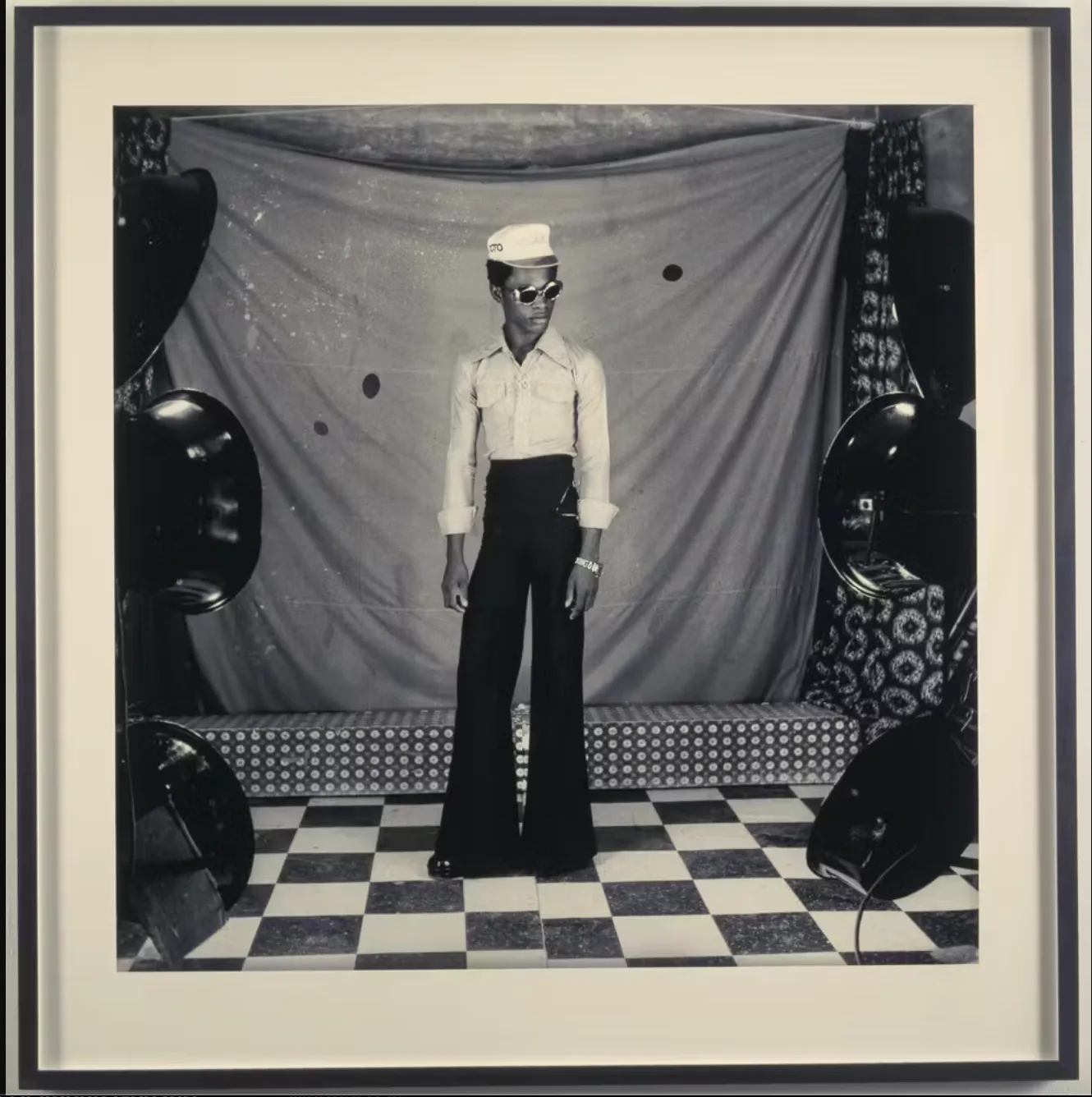

Self-Portrait, 1976, Samuel Fosso

An eternal shape-shifter, Nigerian studio photographer Samuel Fosso uses the camera to transform himself into both fictional and real personas. For Fosso self-portraiture functions as a form of theater. Fosso dons characters as he pleases, from a pimp to a chief to a “liberated woman of the 70s.”

Sartorial Anarchy #5, 2013, Iké Udé

Like Yinka Shonibare, Nigerian-born artist Iké Udé subverts art history by explicitly casting himself as a flamboyant and extravagant dandy. Udé’s canvases—filled with rapturous neon oranges and emerald blues—emanate a love of fashion’s potential for transformation and self-empowerment.

The Playboys of Bacongo, 2007-09, Daniele Tamagni

In his series Gentlemen of Bacongo, Tamagni photographs the seriously stylish members of SAPE, the Society of Ambiance-Makers and Elegant People. Known as “sapeurs,” these devotées of style, located in the Republic of the Congo, are 21st century dandies obsessed with designer menswear. Each sapeur has a unique touch and flair, as seen in Tamagni’s photograph The Playboys of Bacongo. The four young men—undeniably stylish—exude a defiant grace as they pose for Tamagni’s camera. The dandy lives on.