It’s set to be one of the UK’s most visited shows of the summer—Olafur Eliasson’s major survey exhibition In Real Life at Tate Modern has already piqued the public’s attention. The artist’s previous appearance in the Turbine Hall with his sun in 2003 drew more than two million visitors to the museum, and In Real Life looks ready to top that figure. But what does it take to put on such a huge and interactive exhibition?

The making of In Real Life began three years ago when the directors at Tate decided to put on an exhibition dedicated to the Danish artist. That’s when curators Mark Godfrey and Emma Lewis

began to get involved with Eliasson and work with his studio. “It takes time to understand the work and decide on the concept for the show,” Godfrey explains to me on the phone. “There has to be a balance between highlighting the achievements of the artist, and showing something brand new.”

The curatorial process resulted in a list of works decided about eight months prior to opening—but “in the final three months we made a couple of small changes”, Godfrey explains. The Tate team consisted of two curators, two curatorial assistants, one member of staff to handle shipping, as well as teams for public programming, installation and handling, press and communications. They worked together with more than fifty of Eliasson’s studio staff who were involved in planning and putting on the show.

“There has to be a balance between highlighting the achievements of the artist, and showing something brand new”

After three years of work, the moment of installation is usually high-pressure for the curatorial team. “Usually the curator does a lot of work during the installation—for example with the Franz West show, we had to decide where to place each work, and where they should go in relation to each other. For a show like this, where each work is a separate environment, we already knew where we were going to build each work, as that was laid out in the floor plan. However, there were two works that once installed didn’t look quite right, so they are in the same vicinity but have been moved slightly,” Godfrey notes.

In Real Life features works you can touch, smell and walk through—which presents a certain amount of red tape to negotiate. While some works, such as the tunnel of fog, Your Blind Passenger, have to pass rigorous health and safety guidelines for use in public space, others, including Your Spiral View, are regulated by the in-house services team. In this case, it’s up to Tate to decide how the artwork should be used, for example, how many people can be in the work at one time. With works that are in constant use by such large numbers of people, there’s also a lot of upkeep to be done—Godfrey says that several works have already had some maintenance, and that has to be ongoing with such a popular exhibition.

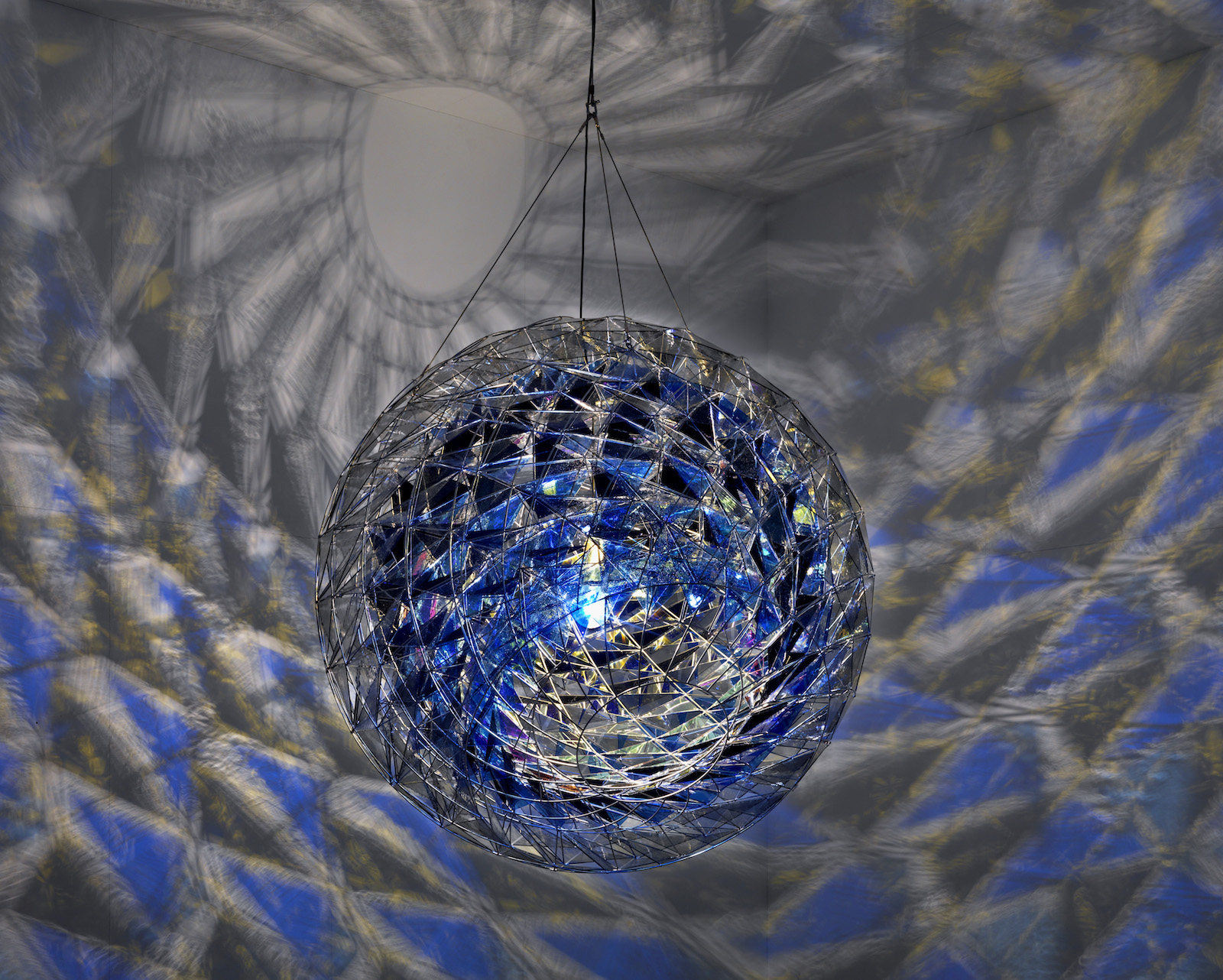

Boros Collection, Berlin © 2002 Olafur Eliasson

“The show on Eliasson was unique in its approach to merchandise, carrying the ideology of the artist’s oeuvre into the items available”

Tate doesn’t use the term blockbuster—but in Eliasson’s case, it’s clear that the interactive aspect of the work is intended to be accessible to a wide audience. Are ambitions for high visitor numbers a priority? “For this type of exhibition specifically we had to think, what would make a successful Eliasson exhibition?” Godfrey reveals. “We wanted people to engage with the work, and to enjoy the installations with light and metal, but also to understand his activism, his thinking about subjects like sustainability, and to want to go and try the food served in the studio kitchen.”

Studio Olafur Eliasson collaborated with Tate Eats over six months to come up with a menu of vegetarian dishes, all using local, seasonal and mostly organic ingredients. “Tate Modern’s head chef, Jon Atashroo spent a week in Berlin exchanging ideas and approaches with the SOE Kitchen team, cooking the seasonal menus that will be on offer throughout the exhibition. Everyone learned from each other, Jon bringing his professional Chef skills to SOE Kitchen,” Hamish Anderson, CEO of Tate Eats, explains. So far, it’s been a well-received collaboration. “The food is absolutely delicious, so it’s going down very well!”

The food is not only intended to appeal to taste buds but to give another culinary dimension to Eliasson’s ideas—art you can taste. “Olafur is passionate about food and social connection, as we are at Tate, he was as involved as he could be between all the other aspects of opening a major exhibition. He has already eaten at the Terrace Bar a few times and we have discussed menus for the Autumn.”

Like many of the major exhibitions that Tate mount, the experience isn’t limited to the exhibition halls. “For a large show we are usually thinking about merchandise from about eighteen months before, especially if we are considering an unusual approach,” says Rosey Blackmore, Tate’s merchandising director. “We like to have an initial conversation with the artists, or their studio or estate, very early on to get a better understanding of what they’d be happy to see us do, and what would feel appropriate. This does vary a great deal, but what we are always trying to achieve is a merchandise selection that reflects the visitor’s experience of a show, and which the artist/their estate is really pleased with.”

Blackmore and her team received initial plans for the exhibition and a briefing from the curator about the content and focus of the exhibition. They then planned in parallel with the exhibition planning as it evolved. As Blackmore sees it, “exhibition merchandise plays a really important role in a museum, allowing people to capture an ephemeral moment that they have enjoyed, and take a piece of it away with them. Many creative people also tell us how much inspiration they take from our shows, and our prints and postcards, in particular, allow them to use that as source material for their own practice.”

Photo: Jens Ziehe, Centre Pompidou, Paris © 2012 Olafur Eliasson

“Olafur is passionate about food and social connection, as we are at Tate”

The show on Eliasson was unique in its approach to merchandise, carrying the ideology of the artist’s oeuvre into the items available to purchase and take home, something that doesn’t happen with every survey show on this scale. “We were challenged by Olafur and his studio to think about how we could do something different for this exhibition, to reflect his deep concern for the environment and sustainability. Through discussion, we came up with this idea of a circular economy experiment where we invite people to bring in an old t-shirt for us to recycle, in return for a discount off their exhibition T-shirt. The idea really seems to have captured people’s imagination, and we’re delighted with the way that it’s working.”

The cost of putting on this enormous exhibition was not disclosed by Tate, but it’s clear the team have invested their hearts and souls. In terms of its prolonged success, In Real Life might just be one of Tate’s most rounded exhibitions, with visitors leaving with the art in their minds, on their backs and in their stomachs.