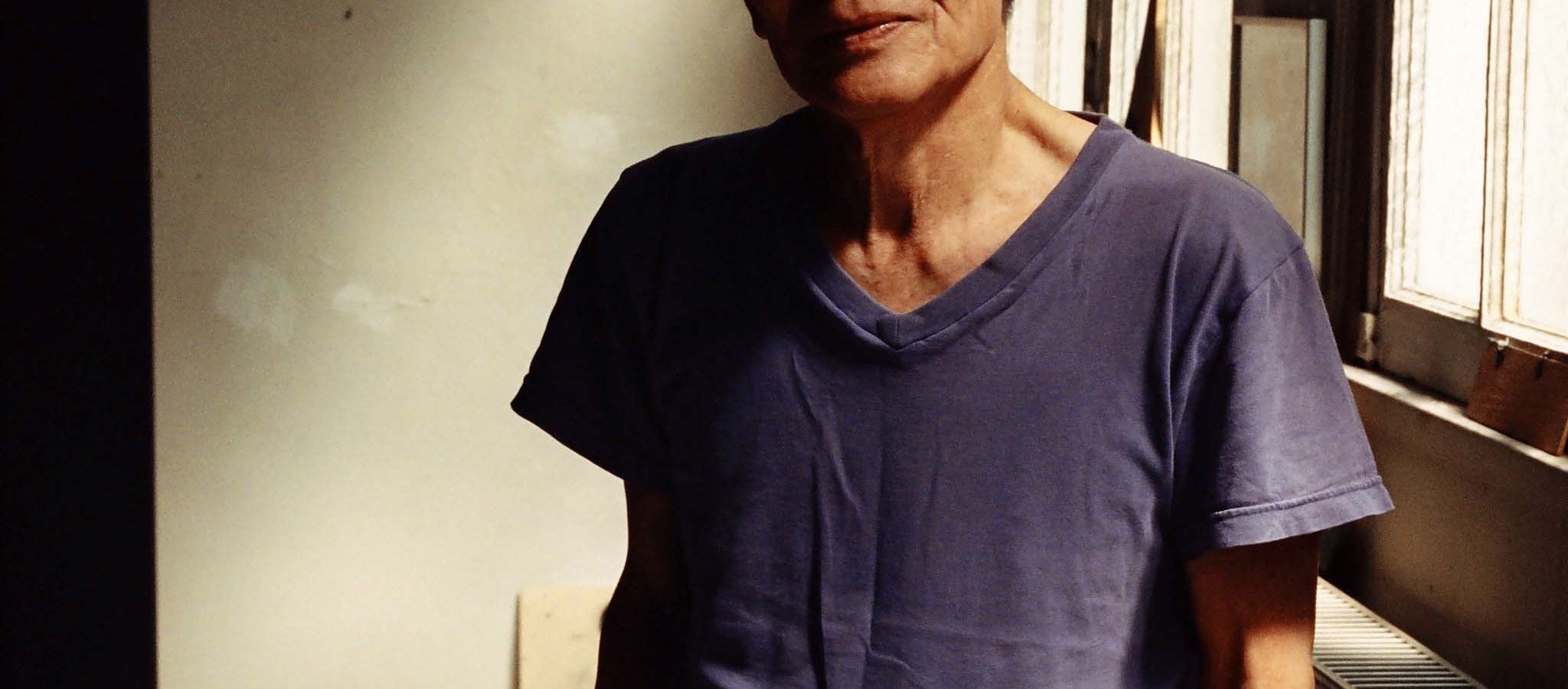

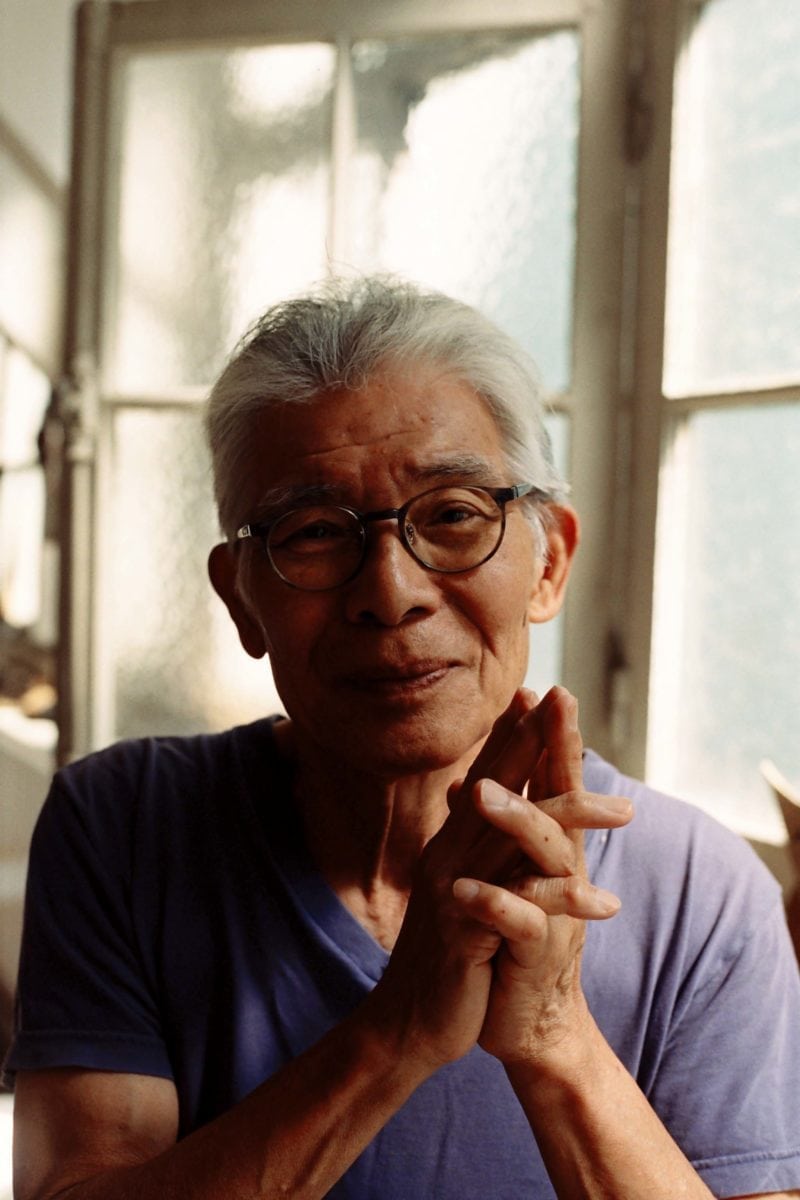

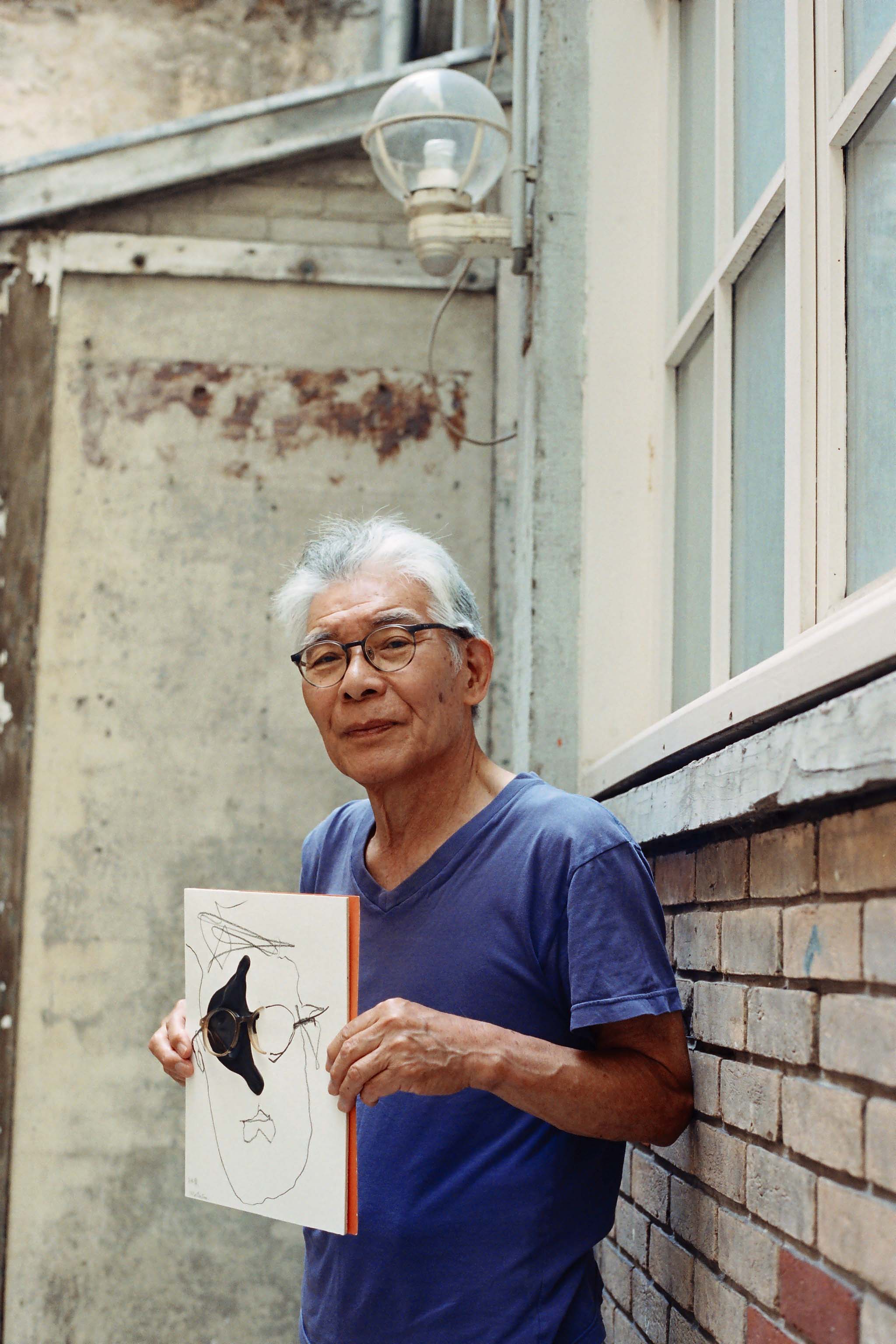

Takesada Matsutani has been firmly implanted in France after decades of expatriation, and yet retains a distinctly Japanese sensibility to his experimental, gestural practice and exploration of unusual materials across evocative, fleshy paintings, drawings and sculptures. He came to France for a scholarship and he stayed for love, not art, he tells me.

Now in his eighties, Matsutani remains prolific, still profoundly marked by his early career experiments as part of the post-war avant-garde Gutai group, founded in the 1950s in Osaka. Armed with buckets of PVC glue and a clutch of electric fans in various states of operation, he creates large canvases with swollen surfaces, their physicality strangely human with their uneven wrinkles and tautness.

Can we talk about In Praise of Shadows, the influential essay on Japanese aesthetics published by Jun’ichirō Tanizaki in 1933? You often cite it as one of the most influential pieces of writing on your work.

I was thinking about aesthetic theory just by chance, really, and I felt a real affinity with this text. I came to Paris when I was twenty-nine, but that meant I had twenty-nine years of absorbing oriental culture. I am from Japan, whose culture is difficult to extract from someone. I kept it with me, but I had to reflect on the way in which this showed through my work. I was thinking a lot about black and white, about the culture of calligraphy; this ink has a very long and well-worn tradition and I wanted to try to recreate it with pencil.

It was 1970 and no one knew me, I wasn’t in any hurry; I worked very slowly and very freely. I kept working with the pencil and I saw how the graphite became black. It was during this time that I read the Tanizaki essay, where he thinks about black and white but also all the variations in shade. For me this is so important. I wanted to experiment with the idea of shadows inside a black and white culture.

“I wanted to experiment with the idea of shadows inside a black and white culture”

Tanizaki speaks about the way in which aesthetics are linked to national culture; he ties it to food and social functions, for example. You started your career among the Gutai group and then went on to work in studios in Paris, where you still live. Have you seen your practice change according to these different cultural contexts?

Gutai started in 1954, I was a high-school student at this time. It was in the wake of the Second World War and we were ecstatic but the country was ruined. Fortunately, our souls were free. We were all full of hope. For those working for the state, this meant the construction of infrastructure and technology, whereas artists sought to inspire themselves with creative energy from across the globe.

In 1966 Kyoto and Paris were partner cities; there was a scholarship available for young artists, and I got to go. It was only the second year that Air France was flying from Japan, prior to that there were only boats or the Trans-Siberian train. It was an interesting epoch. In Japan, in industrial or social terms, I suppose things at that time were very similar, we drove cars, we wore the same fabrics on our clothes, but in terms of education and art history we have a different heritage, and it is for this reason it wasn’t easy to integrate.

“Maybe the bubbles will get smaller and smaller as I get older and older, but us human artists, we want everything to be big!”

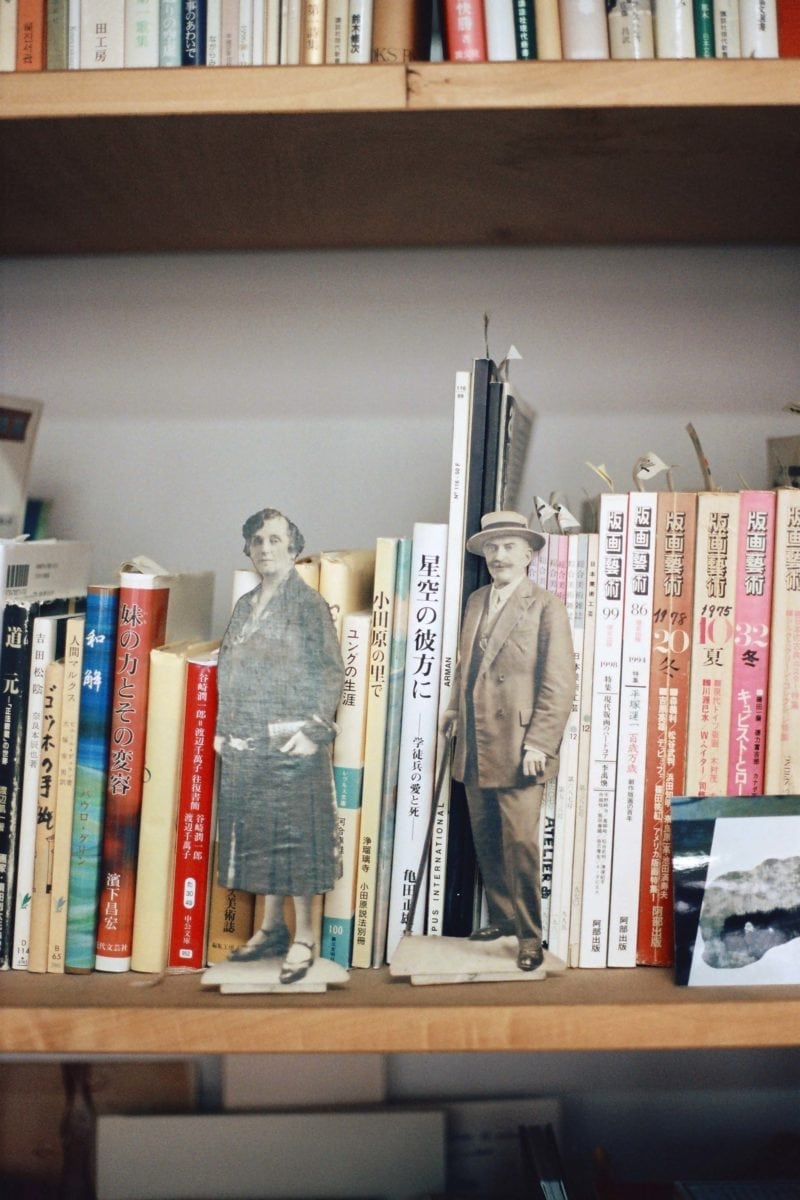

The next year came and went, and I had heard of the Atelier 17 where Stanley William Hayter was working, which opened in the 1920s before I was born. Picasso, Giacometti, Chagall, everybody worked with him. His atelier was open to artists, so I went and knocked on the door and he invited me in. It was in this studio that I met my wife, who was visiting from the States, which is why I stayed until now. It was not about art, it was about love.

I’ve always been interested in the change and the comparison between the Oriental and the Occidental. Deep down, we keep our culture within us, not in a nostalgic way, but the mantra of the Gutai was “make it new”—it was what inspired me to work with graphite and vinyl glue—but eventually I wanted to break these things too. I wanted my imagination, and my soul wanted to go further.

You’re well known for working with this PVC glue. Can you talk about how your most recent works are made?

The large protruding bubbles that feature on these canvases are made by sticking a straw into the drying glue and blowing. I am an old man and my lungs aren’t very strong anymore. Maybe the bubbles will get smaller and smaller as I get older and older, but us human artists, we want everything to be big! I get very tired. I have one assistant but I still like doing things by hand: I like being physically involved in creation.

There is something very poetic about blowing your life force into a piece of work and then sealing it up.

Sometimes I’ll blow it and it will have deflated over night. When that happens I light a cigarette and blow the smoke into the bubble in order to see where the hole is! I don’t smoke, but I like these useful primitive methods! Sometimes I use just my lips to find the small holes.

Can we talk about performance and performativity and the presence of spectators?

Most of an artist’s work takes place within an atelier. What is shown outside of this space is a stopped process; the finished piece is all that emerges. I wanted to be able to also show movement, I want people to witness the lifespan of an artwork. Sometimes my work is created by spontaneous experimentations, sometimes I hang work from the ceiling, I hang it from the beams, and this is important to the way the work emerges. When I create things spontaneously I don’t think and reflect, but the moment of creation is sometimes the most important part of the artwork.

“The moment of creation is sometimes the most important part of the artwork”

You speak a lot about chance and unplanned gestures. It seems as though you are able to create a narrative that is meditative on the creative moment just passed….

I think it’s like jazz. In classical music you have a conductor who maintains control, in jazz you work on improvisation and impulse. My work follows similar lines of improvisation. This is how you come up with something new. You are able to absorb all of this art history, all of these influences, but when you improvise it is unplanned, and you create something new from being imbued with something old.

Photography © Jules Faure