For most of his adult life, the twin poles of painter Frank Bowling’s existence were London and New York. Born in Guyana in 1934, Bowling moved to London in 1953, first visiting New York in 1961 on a travelling scholarship while studying at the Royal College of Art.

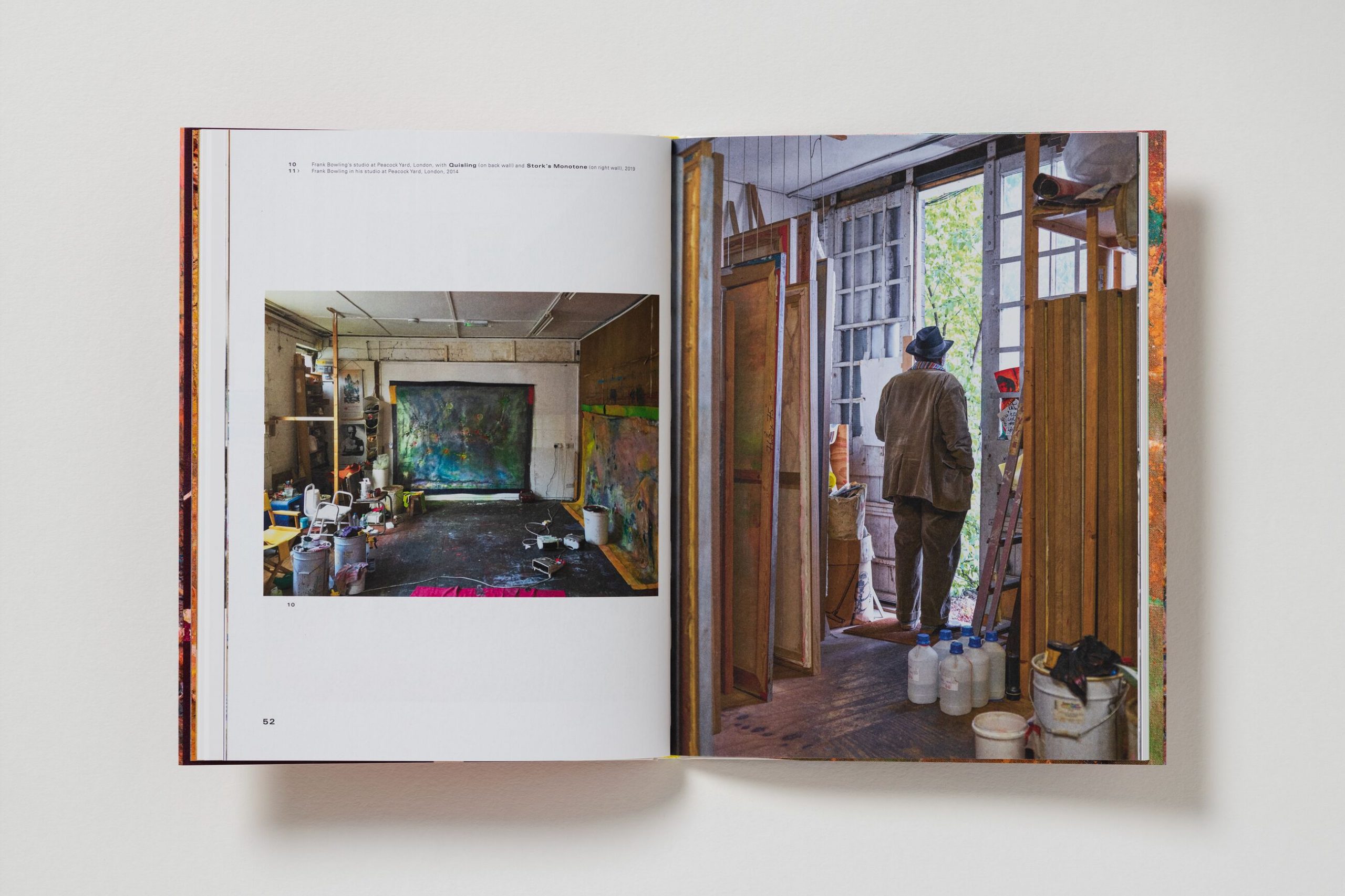

The painter moved there to live in 1966, and, even after returning to London, Bowling continued to traverse the Atlantic, spending springtime and autumn in his East River studio in Brooklyn, and summer and winter on the banks of the Thames. This new book, Frank Bowling: London/New York, coincides with an exhibition split between Hauser & Wirth’s outposts in both cities, and sets out to explore the push-and-pull exerted on an artist living between two places, forever at home yet estranged in both.

What Bowling encountered in 1960s New York was the wholesale reinvention of pictorial space. It was transformative for an artist, who was still toying with figuration. As curator Mark Godfrey recounts in his opening essay in the book, Bowling would bask in the Museum of Modern Art most days, his own work soaking up the liquified examples of the Abstract Expressionist and Colour Field painters he discovered there. Godfrey selects Jackson Pollock as the key influence here, but one can’t help thinking, looking at these weightless, disembodied works with their luminous expanses of colour, that it was Helen Frankenthaler who actually showed Bowling the way.

“What Bowling encountered in 1960s New York was the wholesale reinvention of pictorial space. It was transformative”

But just as important as the methods Bowling picked up were the departures he made from these famous forerunners, his own experiments with painting rooted in abstraction, and yet intoxicatingly of this world too. Most significant were his Map Paintings, perhaps his best known series to date.

In Texas Louise, 1971, a great wash of nectarine, pink and dusky brown is punctuated by a stencilled map, a ghost landmass, itself an abstraction of a teeming continent, hovering in the midst of a sweltering haze. “Bowling used liquid colour to melt away the fixed authority of cartography,” Godfrey writes of this and other map paintings, the notion of borders and nationhood rendered moot by his shifting, shimmering canvases.

For Bowling, even these loose, spectral map works soon began to feel too fixed, too formulaic, and he moved on again, embracing chance, and the unruly potential latent in the liquid principles of his work. While deeply engaged in the question of Black aesthetics, he routinely refused any categorisation which might pigeonhole him as a ‘Black artist’, and he eschewed explicit political commentary, preferring more allusive strategies with which to register his place in history.

“While deeply engaged in the question of Black aesthetics, he refused any categorisation which might pigeonhole him as a ‘Black artist’”

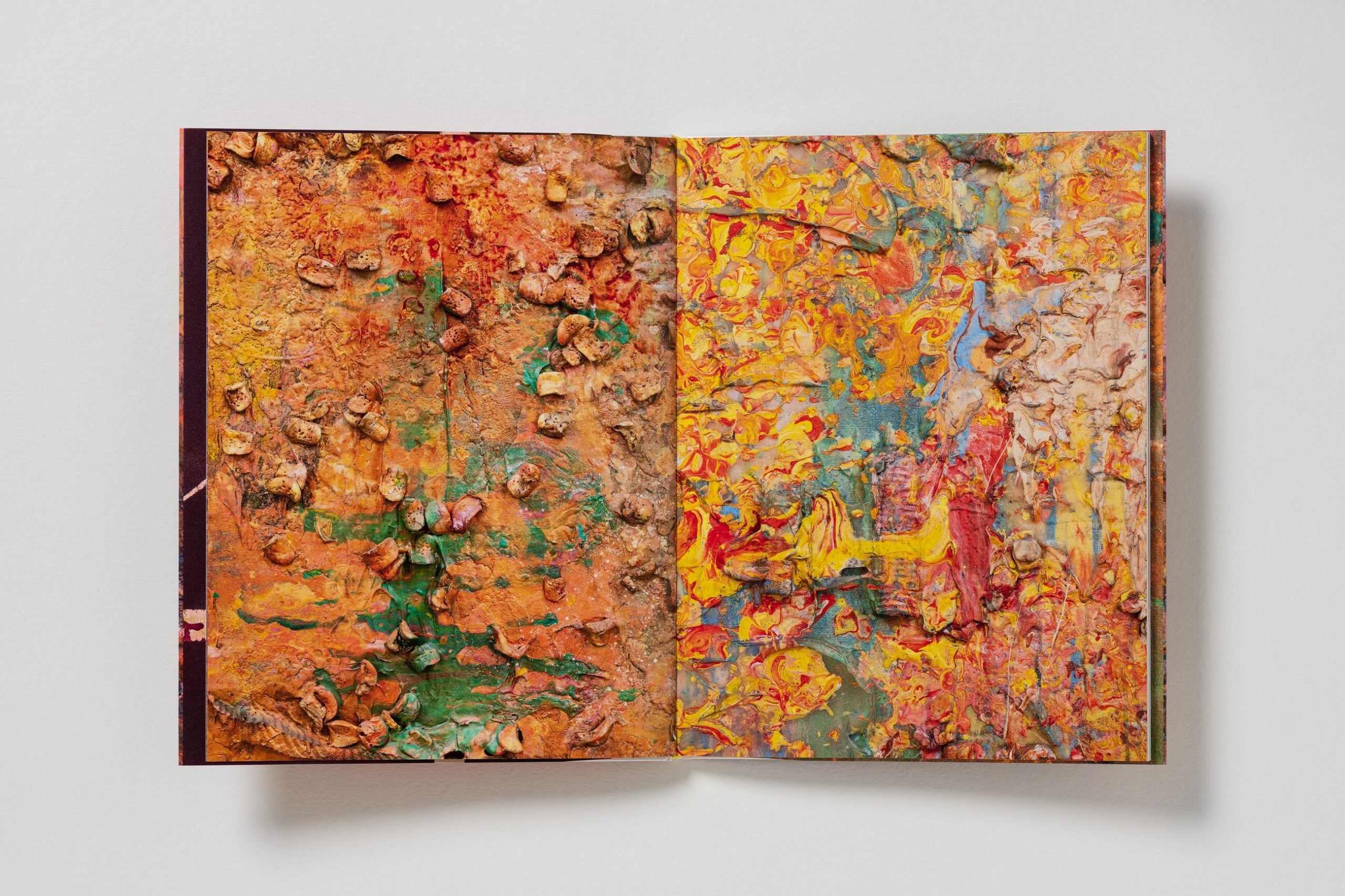

Pouring on to and spraying his canvases allowed him to create effects which were free from predetermined outcome, and from the 1980s he embedded found objects into his surfaces. It introduced a further layer of ingenuity, and recalled, as Godfrey notes, the erratic beauty of the ocean floor.

In the book’s second section, a new conversation between Bowling, his partner, artist Rachel Scott, and his son Ben is transcribed, departing New York briefly, and tracking forward to 1984, when Bowling and Scott spent time in Skowhegan, Maine, for a residency. Here, out in the woods, and buoyed by the support given to his practice, the painter began to experiment, introducing natural elements into his compositions. “Skowhegan gave me license to add material to the works,” he recalls. “A kind of Modernist breakthrough… in competition with what was going on in New York.”

Crucially too, this break from the artistic hothouse of the city allowed the “constitutionally competitive” Bowling (his words) to thicken the surfaces of his paintings. It’s a characteristic which defines his work from the 1980s, densely layering gels, glitter and miscellaneous detritus to make plural the singular plane of the canvas.

This accretive method gave birth to further innovations, the heavy surfaces sometimes needing to be cut into strips and glued onto backing, rebooting the process of composition all over. There is a restlessness to it, an art devised “on the hoof”, as Bowling describes his Transatlantic existence, refusing easy placement, or straightforward legibility.

Obscurity has, in that sense, defined Bowling’s art in more than one sense. Only now, nearing 90 years of age, are his experiments receiving the sustained critical engagement he watched dished out to peers decades ago. This book, a slim, bewitching volume spanning the wide reach of his artistic sphere, reckons with this bittersweet fact, that as the elderly artist’s world shrinks, he is, at last, globally seen.

No matter. Bowling says: “That’s not something to fret about.” His time is now, or perhaps has always been. “The doctor tells me that three hours in the studio at my age is the day—I could do twice that, of course, because I am that way,” he remarks, still very much the artist who needs only to answer to himself. “Ambitious people be ambitious, right?”

Imogen Greenhalgh is deputy editor at RA Magazine

All images courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth