Marble, brass, gold, silk… which materials conjure luxury for you? How about plastic, human hair or discarded tin cans? Our associations as a society are often hardwired to historical ties, from colonial spoils from exotic lands overseas to rare items spared only for the elite. Studio Swine are out to challenge these preconceptions, turning luxury on its head to demonstrate that it’s not what a product is made from that matters, but the thought process behind how it is made that counts. Their research-driven design practice has taken them everywhere from Brazil to China in pursuit of the global journeys that some of the most common products take from manufacturer to retailer.

The duo—Japanese architect Azusa Murakami and British artist Alexander Groves—have worked on projects including a range of combs made of human hair set in resin to mimic tortoiseshell to a series of chairs constructed from melted-down tin cans destined for the waste plant. Together, they explore the stories behind the global flow of commerce and resources to draw into question the cultural, historic and economic ties that we each attach to the products that we interact with on a daily basis. Their work has been widely exhibited at institutions such as the Victoria & Albert Museum in London, Pompidou Centre in Paris, and the Venice Art and Architecture Biennales.

You are represented by Pace and Pearl Lam Galleries, which is unusual for a design-led practice. How do you navigate between the worlds of art and design?

Alexander Groves: We have quite an unusual practice in the sense that my background was fine art and Azusa’s was architecture, and we haven’t felt the need to classify our work as either. We’ve been completely led by what we’re most curious about. We’re interested in making an immersive world and having these objects that you could somehow project yourself into. Increasingly we’ve been doing more public artworks, considering a gallery without walls and moving into the public sphere.

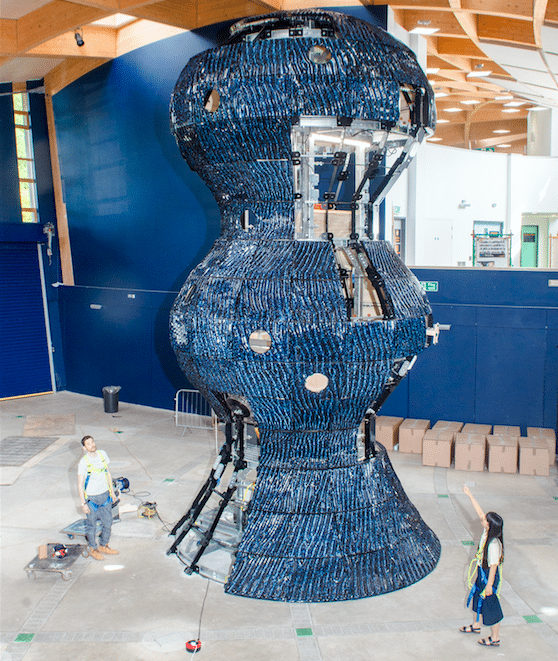

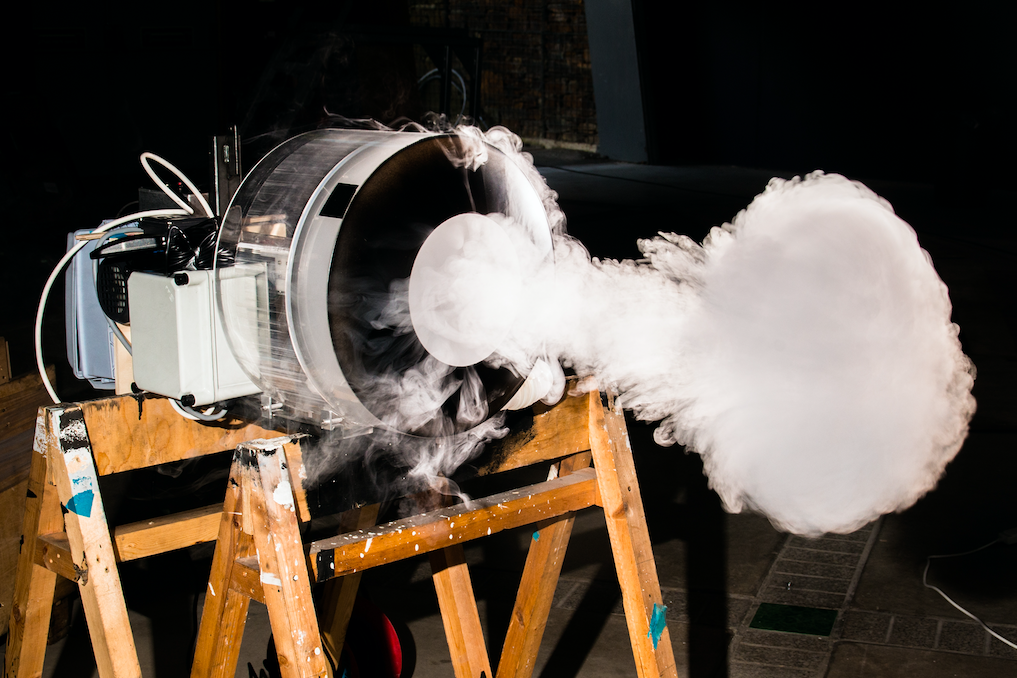

Our most recent work, Infinity Blue, is at the Eden Project. We really threw ourselves into the research and we worked with local microbiologists to look at how our atmosphere was formed. We created a huge ceramic “breathing” sculpture that throws out these scented smoke rings. It controls the weather and all kinds of things that you interact with.

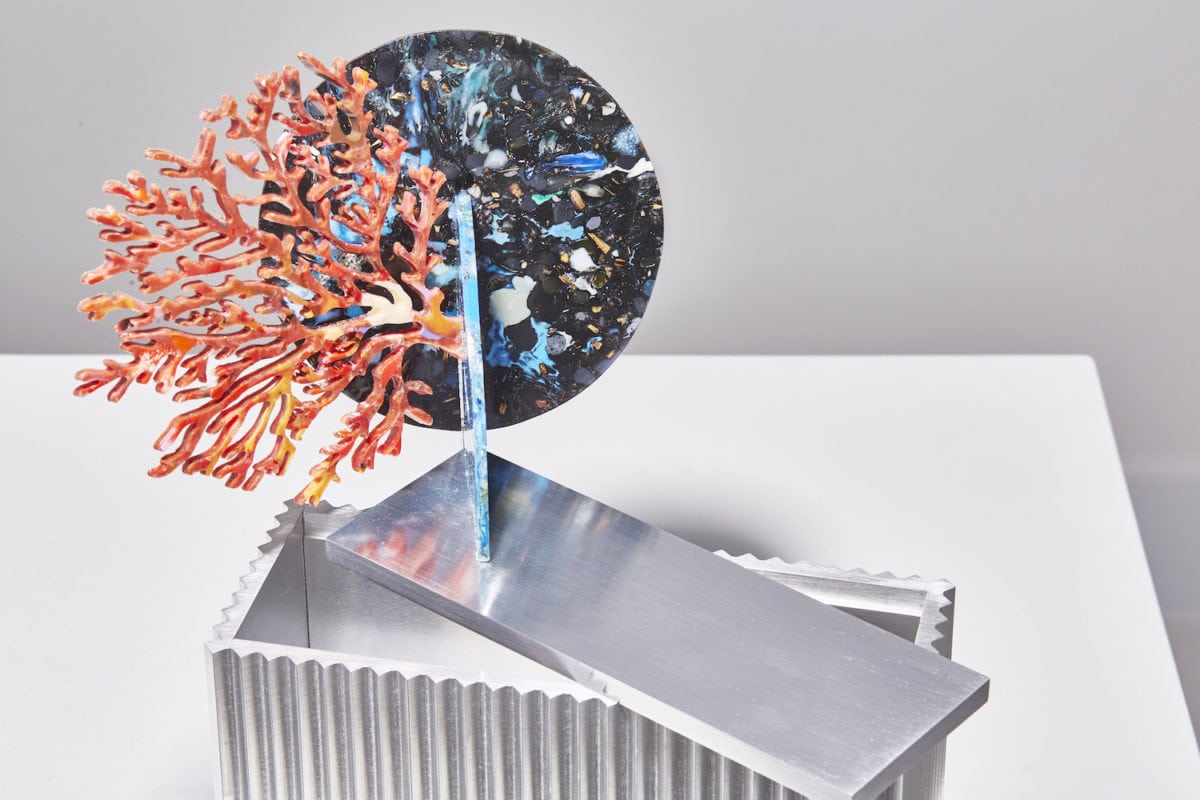

- Can City, 2013

“We’ve been completely led by what we’re most curious about. We’re interested in making an immersive world”

The films that document and accompany each of your projects are an essential part of your practice. Why is this?

Azuza Murakami: For us it’s as much a creative purpose as creating the actual works. We start the process of thinking about the film in tandem with the projects we’re doing, and they influence each other. We’re really interested in creating a world for the work to exist within, and I think that filmmaking is really effective in creating a vision for other people to experience the project—especially if you don’t have a physical gallery space.

- Can City, 2013

Materials and are at the heart of what you do. How do you approach them, and what attracts you to the stories behind them?

AM: We’ve always found that we didn’t just want to use materials that were desirable in themselves, like brass or marble. We see it as a challenge to transform things that are very undesirable or overlooked, like plastic pollution in the sea or human hair, which is reflected also in our name of Studio Swine, which has its own associations that are difficult to overcome. We really enjoy that challenge, and beauty is not just what you see but what you know.

We see the things that we make as a great way to take these unusual trips. It has really led us to places that are completely off the commonly visited map, which we find a really exciting way to explore. The journey that rubber takes around the world from a tree to a Formula One car or plane that still uses 80 per cent natural rubber in its tyres is so extraordinary, and we think that it’s a story worth sharing.

“We see it as a challenge to transform things that are very undesirable or overlooked”

Who are the predecessors to the type of design and research work that you are doing? Are there any figures from the past who you look to for inspiration, such as explorers or others who have tracked these very unusual, largely unpeopled routes?

AM: The direction that we wanted to take with our practice is similar to gonzo journalism, to go in there and through raw experience you change your preconceived ideas. We never know at the beginning of the project what we’re going to do or what we’re going to come out with, we kind of see it like method acting. You absorb as much as possible for the experience to really lead you through the process, and then come out with something that’s very pure at the end.

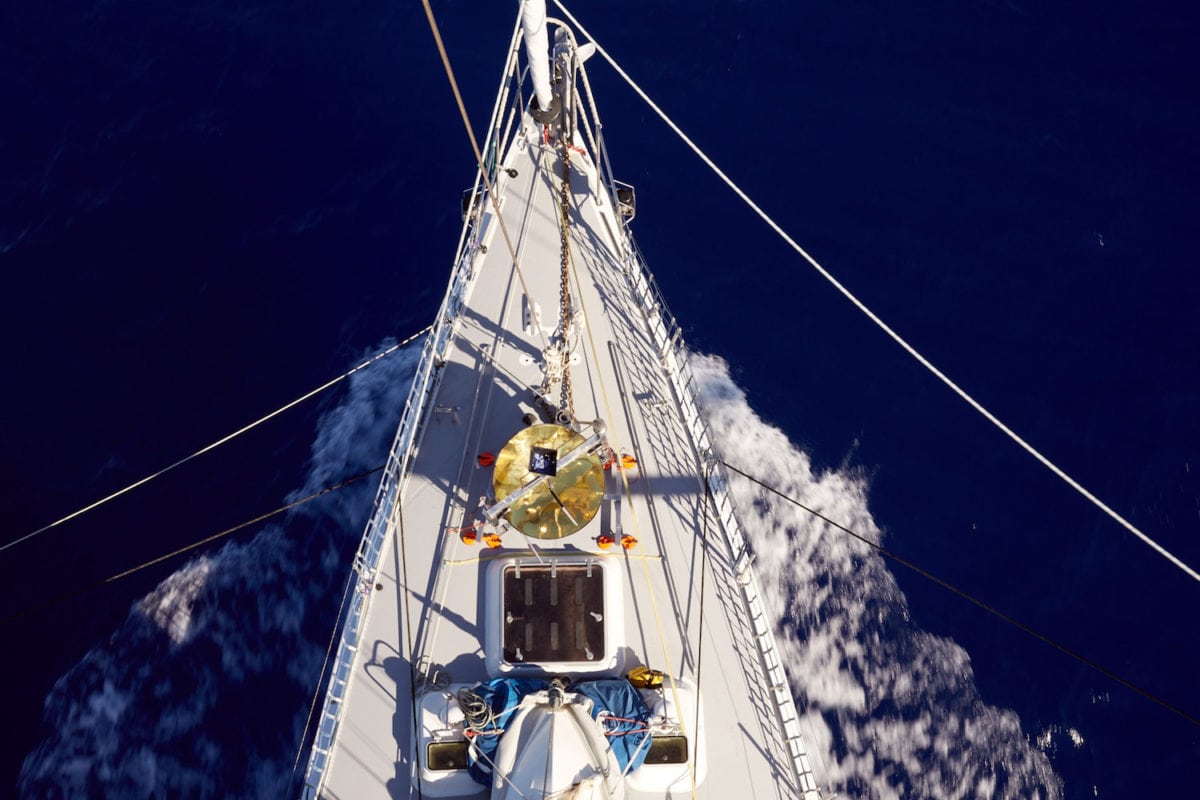

- Gyrecraft, 2015

Luxury is often built on belief, whether that’s belief in a brand or trust in heritage and craftsmanship. It could be extended to incorporate the luxury of time. In the context of your work, what does luxury mean to you?

AG: It’s quite a loaded term, and it can be problematic because it can be seen as undemocratic, but I think that luxury can actually be really accessible. I’ve got a huge amount from the work of Andy Warhol, and I’ll probably never own an original: it can be for everyone. We hope to create experiences and stories that a lot of people can access. We’re really interested in desire as an instigator of change.

You can read more about art and luxury in the new issue of Elephant magazine

BUY ISSUE 36