Life, death, parenthood, disappointment, late capitalism, the concept of technological obsolescence: all big, big ideas, as relevant today in 2020 as they were back in the heady CK One-spritzed days of 1997. The Tamagotchi neatly compacted them all into a little egg shaped fad. If you were a kid in the nineties, chances are you either lusted after one, owned one or broke someone else’s.

Tamagotchi were conceived by toy designer Aki Maita of Japanese company WiZ and Yokoi Akihiro of Bandai; they were later brought to life by Aki Maita in 1996, scooping her the 1997 Ig Nobel Prize for economics. According to the New York Times, Yokoi’s inspiration for the pixel-based critters came from a TV ad showing a boy who wanted to take his pet turtle with him on a trip, only to be scolded by his mother and told to leave it at home. Turtles, of course, aren’t as portable as tiny, plastic introductions to the nature of both life’s transience and the way capitalism ridicules us all. Others have suggested that Tamagotchi’s origins in Japan might be related to the country’s often small urban apartment sizes, meaning keeping “real” pets would be cruel, if not impossible.

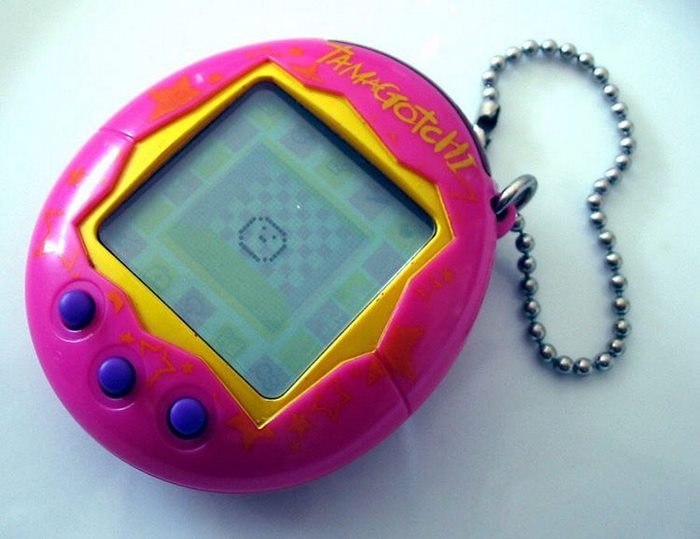

The first incarnation of the Tamagotchi (a name Bandai is said to have claimed is a portmanteau of Japanese words tamago, or “egg”, and uotchi, meaning “watch”) was released in Japan in November 1996, with marketing that specifically targeted teenage girls, and were available to the rest of the world from 1 May 1997, catching on like a bleeping plague.

As anyone who lost their shit for the likes of pogs, or yo-yos (that saw many a boy nearly have someone’s eye out attempting an “around the world”), will know; such fads are sadly short-lived. Fun, noisy gadgets and school have never been the happiest of playmates, and Tamagotchis provided a unique set of problems for teachers and kids in that they demanded constant attention to stave off their inevitable deaths.

“These pets were the birth of the ‘quantified self’, in which our lives take on an almost Orwellian documentation of how ‘good’ we are”

Despite their small, keyring size; they were noisy blighters; and if you weren’t bang on it in terms of feeding, cleaning up their poo, playing with them, etc. etc. they’d beep incessantly. There were also visual cues to help indicate the Tamagotchi’s exact needs—precursors to the way we now communicate with one another through emoji—such as a skull that showed your pet needed medicine, or zzzs that passive-aggressively asked you to turn the light off, for it was bed time.

On reflection, they sound like a massive pain in the arse, but also a prescient encapsulation of so many things we take for granted today. These demands on our attention are now housed in phones, on a technical standard we had no idea would be possible more than two decades ago. The metres that monitored a Tamagotchi’s happiness, hungriness and discipline levels are reminiscent of many of the tools we now turn on ourselves: things like FitBits, step-counters, digital dietary logbooks, sleep trackers and so on.

These pets were the birth of the “quantified self”, in which our lives take on an almost Orwellian (but self-imposed) documentation of how “good” we are when it comes to diet, exercise, sleep, saving/squandering money, having sex and having periods—as well, of course, as monitoring the amount of time we spend looking at our screens to keep an eye on all these things. We might be messy and unpredictable human beings, but we are data-mineable ones all the same.

Tamagotchi have proved time and again to be a rich source of rip-offs, reboots and reverie-like nostalgia. This could, of course, be something to do with that apparently endless fetishization in recent years of all things late-nineties (see also fanny packs, Spice Girls reunions, bucket hats, Buffalo shoes; the list is endless). It could also be that they’re just like any other fad, reminding us of simpler times when we were so young we really could fixate on something as simple and fleeting as a small virtual alien.

However, it could also be posited that the design of the Tamagotchi itself, and the way it was marketed as “girly” (to use an unpleasant, thankfully outdated, marketing term) in lurid pinkish tones, high-pitched squeals, and sparkles was a subtle tool that served to underscore the role of girls as nurturers and carers. There we were, feeding, cleaning up the poo, doling out constant attention (or filling its “happy metre”).

“It could be posited that the ‘girly’ design of the Tamagotchi itself was a subtle tool that served to underscore the role of girls as nurturers and carers”

Women’s age-old duties were all here in force, albeit wearing a digital interface and encased in flimsy plastic, sold back to us just at the age we were to transition from mothered to mothers-in-waiting. The responsibility for the critters is on the user, and is very visible: the UI is designed so that each Tamagotchi character’s appearance undergoes several changes before reaching its “adult” form; and its shape, personality and life span are all utterly dependent on the kind of care it receives.

Maybe Tamagotchi were helpful, in a way. After all, they teach lessons about transience, disappointment and death, time and time again. Or, maybe, they’re just a bit of fun. Whatever the nature of our weird Tamagotchi-adoration, it doesn’t appear to have waned: Bandai released a second wave of the toys in 2004, and to much fanfare in 2017 the originals were re-released to mark their twentieth birthday. In their small way, the originals were prescient bellwethers of the way we interact with pocket-sized digital devices today in ways surely few could have predicted, which have become, in a sense, our own bleeping, happiness-metered personal Tamagotchi.